Specimen of the Week 209: Mammoth tusk

By Tannis Davidson, on 12 October 2015

This week’s Specimen of the Week is one of the first objects to be seen upon entering the Museum. Majestically, it sits just behind the front desk cradled in a graceful arc of perfect balance and symmetry. It is the largest fossil in the Grant Museum’s collection and although incomplete, measures over 1.7m in length. What a beaut! This week’s specimen is…

**The Mammoth Tusk**

Mammoth tusk LDUCZ-Z2978 Mammuthus primigenius behind the giant deer skull LDUCZ-Z800 Megaloceros giganteus

1. Primo

Of all the extinct ice age giants, possibly the most iconic was the woolly mammoth. One of several mammoth species, Mammuthus primigenius was the last species of the genus, dying out around the time of the last glacial retreat. They lived during the Pleistocene epoch from 120,000 years ago to 10,000 years ago (in Europe and southern Siberia) and even later until 3700 years ago on isolated islands such as Wrangel Island in the high Arctic ¹.

2. Looking good

Much is known about the appearance of mammoths from the numerous frozen carcasses, remains, teeth and tusks which have been found in Siberia and North America. Every child can describe the shaggy haired, long-tusked elephant cousins. Mammoths proudly feature in ice-age related museum displays, books and films. As recently as last week, a Michigan farmer discovered the remains of a near-complete mammoth while excavating on his farm.

Mammoths are also known from the prehistoric art and cave paintings made by our human ancestors who lived alongside (and hunted) woolly mammoths during the late Pleistocene. Cave paintings in Spain and France such as Rouffignac Cave “the cave of the hundred mammoths”, depict woolly mammoths alongside other ice age fauna:

![By Cave painter (Own work) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://blogs.ucl.ac.uk/museums/files/2015/10/Grotte_de_Rouff_mammut.jpg)

Cave painting in the Grotte de Rouffignac. By Cave painter (Own work) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Fast forward several thousand years, and a new hunt is on. In the last few decades, a tusk-rush has been happening. In the Russian arctic, the contributing factors such as the international ban on trading elephant ivory (and the search for alternatives) as well as the continued thaw of the permafrost have galvanised “frontier capitalism” and fueled the mammoth tusk trade ². Every summer when the tundra melts, hundreds (if not thousands) of mostly local people scour the landscape in hopes of finding an exposed tip of mammoth tusk in which to extract, take to market, and sell. Mammoth ivory is legal and it has been hoped (but not yet realised) that it would reduce demand for illegal elephant ivory. Nearly 60 tonnes of mammoth tusk are exported to Hong Kong each year ³. Despite this, the unquenchable demand for ivory (mainly sold to the Chinese mainland to carve into objects sold as art) has led to an increase in African elephant slaughter ⁴.

4. The Grant Tusk

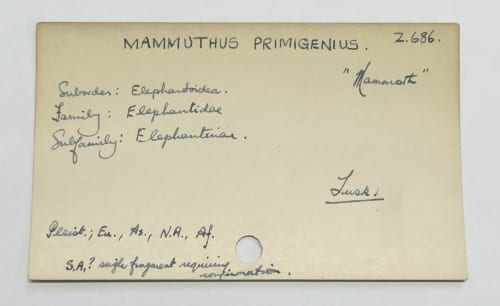

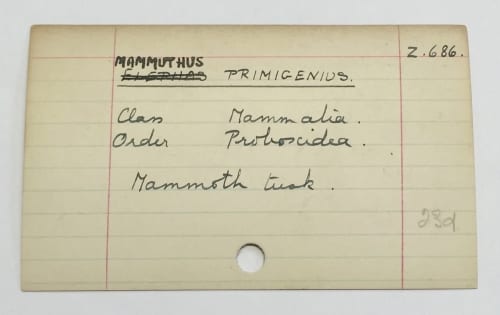

While it is not known where the Grant Museum’s mammoth tusk came from, we do know when it came into the collection. Our tusk is first listed in the Grant Museum’s 1900-1901 card catalogue:

The sharp-eyed among you will see that it has an accession number of Z686 (also recorded in the Museum’s accession record). Somewhere along the line, the number became separated from the tusk and the details were not transferred to a database record. So, over a hundred years later, Z686 became Z2978 when it was recently (re)accessioned. Now as a result of a little SOTW-related research, the two numbers have been reconcilled and the tusk has been reassociated with its archival documentation.

5. Woolly reboot?

It seems that the subject of bringing the mammoth back to life is as alive as some scientists suggest the mammoths could soon be. Geneticists have recently decoded most of the woolly mammoth’s genome sequence providing a blueprint for making a mammoth ⁵. Also this year, geneticist George Church‘s lab at Harvard University successfully copied woolly mammoth genes into the genome of an Asian elephant essentially making mammoth genes functional for the first time since extinction ⁶. Spectacular science, no doubt, but along with these developments come the debates surrounding the ethics of de-extinction (read Beth Shapiro’s Guardian article here).

Tannis Davidson is Curatorial Assistant at the Grant Museum of Zoology

References

- Arslanov, K., Cook, G.T. , Gulliksen, S., Harkness, D.D., Kankainen, T., Scott, E.M., Vartanyan, S., and Zaitseva, G.I. 1998. “Consensus Dating of Remains from Wrangel Island”. Radiocarbon 40 (1): 289–294. [online] https://journals.uair.arizona.edu/index.php/radiocarbon/article/view/2015. Accessed 2015-10-06

- Larmer, B. 2013. “Of Mammoths and Men”. National Geographic Magazine. April 2013. [online] http://ngm.nationalgeographic.com/2013/04/125-mammoth-tusks/larmer-text. Accessed 2015-10-06

- Martin, E. and Martin. C. 2010. “Russia’s mammoth ivory industry expands: what effect on elephants?”. Pachyderm No. 47 January-June 2010: 26-35. [online] http://pachydermjournal.org/index.php/pachy/article/viewFile/171/107. Accessed 2015-10-07

- Convention on the Internation Trade in Endangered Speicies of Wild Fauna and Flora. 2013. “New figures reveal poaching for the illegal ivory trade could wipe out a fifth of Africa’s Elephants over next decade”. [online] https://www.cites.org/eng/news/pr/2013/20131202_elephant-figures.php. Accessed 2015-10-07

- Palkopoulou, E. , Mallick, S., Skoglund, P., Enk, J., Rohland, N., Li, H., Omrak, A., Vartamyan, S., Ponar, H., Götherström, A., Reich, D. and Dalén, L. 2015. “Complete Genomes Reveal Signatures of Demographic and Genetic Declines in the Woolly Mammoth”. Current Biology Volume 25, Issue 10: p1395-1400, 18 May 2015. [online] http://www.cell.com/current-biology/abstract/S0960-9822%2815%2900420-0. Accessed 2015-10-07

- Fecht, S., 2015. “Woolly Mammoth DNA Successfully Spliced Into Elephant Cells”. Popular Science. [online] http://www.popsci.com/woolly-mammoth-dna-brought-life-elephant-cells. Accessed 2015-10-07

Close

Close