Specimen of the Week 204: The ringtail skeleton and tail skin

By Jack Ashby, on 7 September 2015

For the past couple of weeks we’ve been closed to the public while works began to replace our ancient heating system. This means that my favourite parts of the Museum (basically where the marsupials are) have been out of bounds, and so I’ve had to branch out somewhat beyond my usual cabinet to select my Specimen of the Week.

I’ve kept it topical, to link with recent zoological (specifically genital) social media trends, and also to an animal that shares its name with a group of marsupials.

This week’s Specimen of the Week is…

**The Ringtail**

1) #NotACat

Ringtails (Bassariscus astutus) are North American members of the raccoon family. They have a ring pattern on their tails, which means that particular common name is fairly sensible (though could be potentially confused with ringtail (or ring-tailed) possums, lemurs, ground squirrels and mongooses).

Not so for their other common names – ring-tailed cat (it’s not a cat), ring-tailed civet cat (it’s not a civet (which in turn also aren’t cats)), or cacomistle (which is more accurately the name of the other member of the Bassariscus genus, B. sumuchrasti, found slightly further south).

It’s also called miner’s cat, which alludes to a reported habit of associating itself with early mining camps, to enjoy the mice they bring. That’s fine and everything, but it remains not-a-cat.

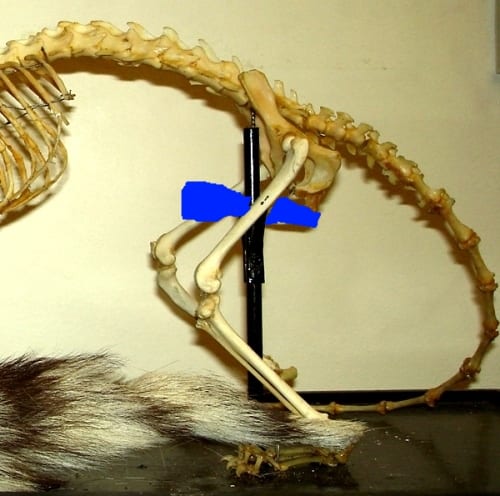

This specimen is among the tiny number in the Museum which is part skeleton, part skin – the eponymous tail is displayed in the case. (Another such specimen is a penguin skeleton with one feathery wing).

2) Raccoon in residence

Like many raccoons, ringtails have a broad ranging diet, including fruit, small mammals, insects and birds. They are found in Mexico and southern USA, where they are regularly found in and around human habitations. The relationship that started with early settlers and miners (which got them that common name) appears not to have changed.

![A ringtail Robertbody at en.wikipedia [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://blogs.ucl.ac.uk/museums/files/2015/08/Squaw-ringtail-28073-300x199.jpg)

A ringtail

Robertbody at en.wikipedia [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

3) Familiarity breeds death

Despite being scientifically cute, thousands of ringtails are legally shot by American fur-hunters every year (50,000 in 1980s Texas alone*). This is despite the fact that their pelts are thin, wear-out easily and readily fade. They can fetch less than $5 each. According to the IUCN, who rate the species as “Least Concern” for conservation, “The justification for trapping ringtails for fur is weak, especially since in none of the states where trapping is legal is there sufficient knowledge of population levels and trends on which to base valid harvest regulations.”

4) #JunkOff

As covered by a number of reputable news outlets, zoologists the world over (myself included) have recently been sharing images of animal genitalia on Twitter, by using the hashtag #JunkOff, in the name of popularising science.

And it only took the tiniest nudge to learn that zoologists everywhere were hoarding pics of animal penises. #JunkOff pic.twitter.com/RfkhuGqWQ3

— Jack Ashby (@JackDAshby) August 26, 2015

Our ringtail skeleton is unique in the Grant Museum (as far as I have noticed) in that it still has its penis bone mounted. Most mammals have bones in their penises – including primates (but not humans), rodents, moles, shrews, hedgehogs, carnivorans (including ringtails) and bats. There’s a really handy acronym to remember that but it’s borderline sweary, so maybe tweet me if you’re super keen. However, Victorian (and later) prudishness resulted in the vast majority of these bones – and their clitoris counterparts – being removed from museum displays and hidden in drawers. Yet more evidence that museums lie all the time.

Jack Ashby is the Manager of the Grant Museum of Zoology.

[UPDATE 11/9/2015: Somewhat ironically, Paolo Viscardi (who will be joining the Museum as its new Curator next month) saw this post and re-identified this skeleton as a cacomistle (Bassariscus sumichrasti), rather than a ringtail, based on the distinctive morphology of the penis bone of the two members of this genus.

The irony is not lost on me that this post is about penis bones, museums misleading visitors (by removing penis bones); and that I derided the use of the name “cacomistle” for ringtails.

We will update the catalogue entry for this specimen as a result.]

*While I haven’t been able to find more recent data for Texas, harvest reports for Colorado, Utah and New Mexico suggest modern numbers are lower in these states. (2013-14 New Mexico Hunter Harvest Report Program. Summary of Results–Furbearers; Utah Furbearer Annual Report 2011–12; Colorado Parks and Wildlife Furbearer Management Report 2013‐2014 Harvest Year). With thanks to the IUCN Small Carniviore Specialist Group for those reports.

One Response to “Specimen of the Week 204: The ringtail skeleton and tail skin”

- 1

Close

Close

[…] It also suggests that the specimen was prepared and mounted without the prudishness that many historical mounts were affected by (see Jack Ashby’s comments about this in his post on the Grant Muesum’s Ringtail). […]