Specimen of the Week 198: Ammonite-ee-hee*

By Mark Carnall, on 27 July 2015

In both sad and happy news, I’m off to pastures new at the end of August, leaving the Grant Museum after what will be ten years and off to the Oxford University Museum of Natural History. Although that’s still a while away yet, the schedule for the specimen of the week writing mean that this will be my last specimen of the week.

One question I get a lot working at the Grant Museum is “What is your favourite specimen?”. My normal answer is that it changes from week to week depending on what I’ve recently been working on or the specimens I’ve become familiarised with which have been requested for use by researchers. However, I do have a soft spot for this week’s specimen of the week which has been used in teaching and research and hundreds, if not thousands of people have got hands on with this specimen in family and school handling activities. I was pleasantly surprised to find that it hadn’t already been featured in this blog series either.

This week’s (and my final) specimen of the week is…

** An Ammonite Fossil**

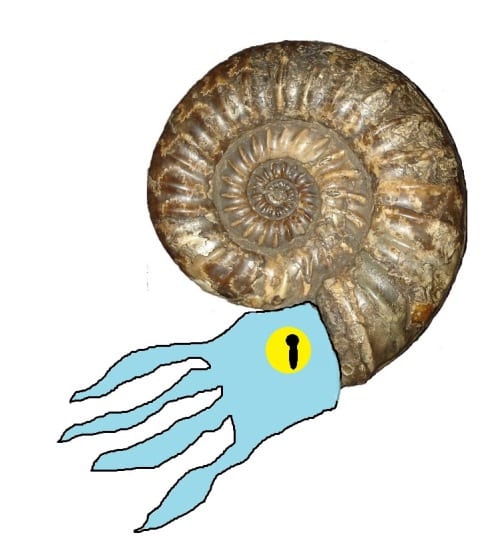

LDUCZ-R16 Asterocera obtusum from the Grant Museum of Zoology UCL. This fossil measures roughly 13cm in diameter.

1) A fossiliferous history

From contemporary accounts, the museum’s founder Robert Edmond Grant used both recent and fossil specimens in teaching zoology and comparative anatomy. This fossil ammonite, labelled under an old name Ammonites obtusus is probably one of the fossils which has been in the collection the longest and is listed in the first catalogue of the collection compiled in 1890. After dinosaurs, and along with trilobites, ammonites are probably the most commonly recognisable fossil organisms and I’ve written ammonite x trilobite fanfiction on this blog in the past (a tale of forbidden love called Ancient War and still seeking a publisher).

2) Squid in a shell

Ammonite fossils are the preserved remains of extinct cephalopod molluscs that resemble today’s Nautilus but are probably more closely related to octopuses, cuttlefish and squid. The spiral shell of the animal grew with the tentacled animal inside and the empty chambers would have been used to provide buoyancy as the below reconstruction goes some way to depict. Although the shells of ammonites most closely resemble the living Nautilus and some forms closely resemble the internal shell of Spirula (which I have written about in the past) it is thought that ammonites and coleoids (octopuses, squid and cuttlefish) evolved from shelled nautloid ancestors. This shell has been lost through evolution in most squid, octopuses and cuttlefish. Ammonites were a hugely diverse group with tens of thousands of species which first appear in the fossil record 400 million years ago and finally went extinct around 65 million years ago.

Reconstruction of LDUCZ-R16 Ammonite reconstruction by up-and-coming-young-looking-palaeo-artist to ever so marginally improve public understanding of what an ammonite may have looked like. Colours, numbers of tentacles no indication of actual ammonite.

3) A really useful fossil

Given that this fossil has been in the collection since at least 1890, this specimen has seen a lot of use over the years. In addition to original comparative anatomy classes, this specimen is used in formal teaching today in sessions we run for museum studies and arts and sciences students. In addition, in my comparatively short time here this specimen has been used in countless school sessions in and out of the museum, is a regular feature in our ever popular Fossil Forage family activities and has traveled up and down the country for use in science festivals and roadshows. Because it is dark and shiny it has also been used extensively in testing the limits of 3D colour laser scanning over the years which have issues with dark shiny materials.

4) Wear ‘n’ share

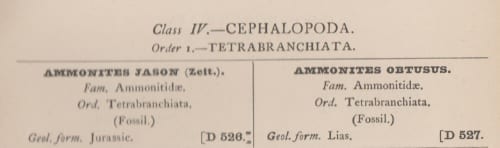

Although it’s a fairly robust specimen, all the use has taken its toll on the specimen in that the original inscription on the specimen is all but worn away. Fortunately, the original inscription is recorded on our collections database and used to read: ‘Ammonites obtusus Lias D.527′. Ammonites obtusus is the old name for this species, the correct name is probably(?) Asteroceras obtusum. Lias refers to both a possible collection locality and age of the specimen. It was collected from the Lias Group rocks which outcrops (it is exposed) from the south coast of Dorset up to Yorkshire and ranges from 180 to 205 million years old. D.527 is a direct link to the 1890 catalogue of the collection, a numbering system which was temporarily used but then later discarded, if you’re interested in that kind of thing.

Original catalogue entry on the right under the old name from 1890 Lankester label catalogue of the Grant Museum collection

5) Horns and Snakes

Any decent introductory reference book to fossils and palaeontology will recall two facts about ammonites. The first is that the name ammonite refers back to one of the earliest references to fossils in the historical record, in the first century, Roman scholar, Pliny the Elder refers to these fossils being seen as sacred in Ethiopia as Hammonis cornu, the horns of Ammon, originally a horned Egyptian god who later fused with the Sun god Ra, and was later worshipped by the Greeks as Ammun. Interestingly for word geeks, ammonia, and the cornu ammonis in brain anatomy also share the same origin as does the Semitic kingdom Ammon, the people of that kingdom, the ammonites, modern city Amman and the extinct Hebrewic language Ammonite. A few hundred years after Pliny the Elder, ammonites were described as snake stones relating to a legend of St Hilda who had turned snakes into stones and specimens can be found in museums that have been carved to depict the head of snake at the end of the coil. There’s a nice summary of the legend and some carved fossils from the Natural History Museum on the British Museum website.

* A la Ms Dy-Na-Mi-Tee for those of who remember 2002.

Mark Carnall is the Curator of the Grant Museum of Zoology

3 Responses to “Specimen of the Week 198: Ammonite-ee-hee*”

- 1

-

2

Documenting Cephalopods Part 3 Labels, labels, labels | Fistful Of Cinctans wrote on 24 November 2017:

[…] a label catalogue that Lankester had printed in 1890 and I coincidentally wrote about some of the cephalopods in the Grant Museum catalogue. Lankester left UCL to come to Oxford University in 1890 and it looks like he brought a few […]

- 3

Close

Close

So sad to hear that you’re leaving! Your successor should be encouraged to write a blog series at least half as underwhelming as your fish.

I am sure that I speak for many readers when I say that I look forward to seeing the work of the next generation of palaeo-artists, and wish you all the best in the future.