Soon turned out we had a heart of papier-mâché

By Mark Carnall, on 16 June 2015

Every year UCL Museum Studies students get to choose an object from each of UCL’s museums and collections to research for a term. This is a guest blog by Jennifer Esposti one of this year’s students looking at a mysterious model.

Greetings! My name is Jennifer and I am a postgraduate student in UCL’s Museum Studies program. As part of my MA, I took a course called Collections Curatorship. This course entailed working within a group of students to research a museum object. I was assigned to the natural history group, to investigate an object from the Grant Museum. My group and I were presented with three possible objects and we selected a crocodile heart model known as Object LDUCZ-X118. Here’s what we found out.

The Assignment

The objective of Collections Curatorship is to introduce students to the core skills of a curator: researching objects in a museum context, and utilising objects in exhibitions. Our assignments for the course were to write an in-depth collaborative report on X118 in ten weeks. Not much was known about the model, it was speculated that it was made of wood and we were charged with finding out what and who may have made the model, whether it was a one-off or part of a series and if possible how old this specimen was.

Object examination

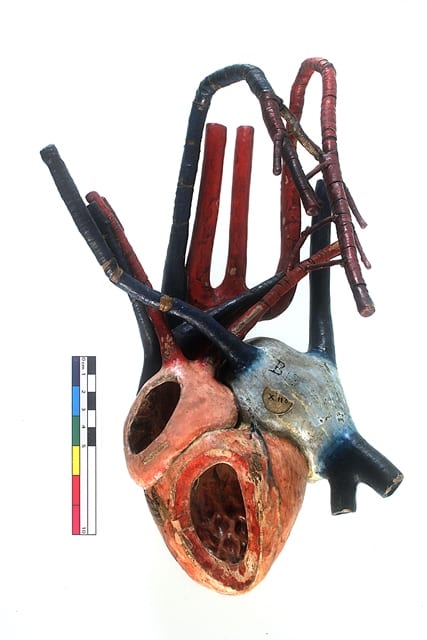

Object X118 is an ‘anatomically correct’ model of a crocodile heart. The model was produced with an impressive level of detail, especially with the interiors of the exposed ventricles. This suggested that the model could have been used for teaching purposes. The anatomical parts of the heart were labelled in French, which suggested that the model was produced by a French manufacture. X118 is part of a set also containing dugong heart and turtle heart models. It is possible that all three models shared an origin and history.

Research

In addition to our research on the information gleaned from the object examination, we researched other areas relating to the history of anatomical models, comparative anatomy, and the Grant Museum. We found that anatomical models were made by anatomical studios and suppliers all over Europe to supply universities, museums and hospitals to teach students. The models produced by Dr. Louis Auzoux stood out to us in particular.

Dr, Auzoux began making papier-mâché anatomical models in the 1820’s. The models were used for teaching comparative anatomy and acquired by universities for that purpose. Since Robert Grant came to UCL to teach comparative anatomy it is probable that the models were acquired then as teaching aids. A catalogue produced by Dr. Auzoux shows that crocodile heart models were sold during the time that Grant and his successors were acquiring specimens for UCL’s teaching collection.

Crocodile hearts have been studied for hundreds of year but the extent of their uniqueness and complexity has only been discovered in recent decades. At the time there was a limited understanding of crocodile physiology and anatomy, demonstrated by the fact that the crocodile heart models is listed in Dr Auzoux’s catalogue as an amphibian rather than a reptile. Crocodile hearts differ from other reptiles in that they contain four chambers, likes those of mammals and birds. The four chambers and a unique shunting system allow crocodiles to stay submerged underwater for extended periods of time.

Comparison

We sought out examples of Auzoux’s models in other museum collections for comparison. We found numerous museums worldwide whose collections contained Auzoux models. The collection that was the most helpful for our research purposes was that of Museum Boerhaave in Leiden Netherlands. Their collection contains a crocodile, dugong, and turtle heart models that are nearly identical to the models at the Grant Museum. The models at Museum Boerhaave are all attributed to Dr, Auzoux.

Materials analysis

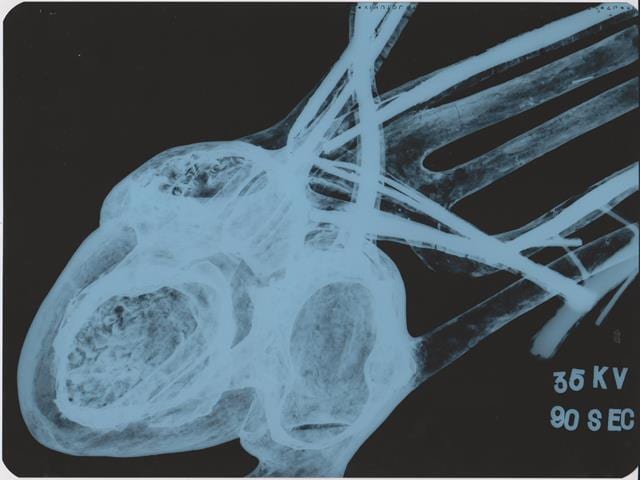

We used materials analysis to examine parts and materials of the model. We were able to confirm that the model was most likely made of papier-mâché which was the medium used by Dr. Auzoux. An x-ray revealed that the veins and arteries were made with wires wrapped in an organic substance. This evidence suggests that the wires were used to support and strength the vessels.

Conclusion

We were able to demonstrate that Dr. Auzoux likely produced X118. Despite our best efforts, it remains unknown how, and when, the crocodile heart model became part of the Grant Museum’s collection. We were unable to locate any documentation regarding the model’s entrance into the collection. The first (incomplete) catalogue of the collection was compiled by Grant’s successor, Edwin Ray Lankester, beginning in 1870. The crocodile and dugong heart models are both featured in this catalogue suggesting that the models were acquired early on in the collection’s history.

We found the crocodile heart model to be a historically significant object that demonstrates both the papier-mâché modelling technique and the role that anatomical models have played in the teaching of comparative anatomy. While these objects are no longer considered to be the best resource for studying biology and medicine, they have become valuable objects in museums throughout the world.

Ultimately, this experience gave us a brief glimpse into the work of a museum curator. While our research provided some useful information on the origin of X118 and its value as a historical object there are several avenues that could be pursued further. We ended the research project feeling happy with what we have discovered but overwhelmed with all the questions that remained unanswered.

Jennifer Esposti is a Museum Studies Masters student at the Institute of Archaeology, UCL.

One Response to “Soon turned out we had a heart of papier-mâché”

- 1

Close

Close

[…] wrote up a blog post for the Grant Museum of Zoology that summarises the work my group did for our Collections […]