The Edwards Museum

By Alice Stevenson, on 4 March 2015

The Petrie Museum takes its name from famed archaeologist Flinders Petrie. It’s all too easy, therefore, to fall into the habit of always celebrating him – all ‘Petrie this’ and ‘Petrie that’ – as if he somehow toiled alone, a heroic pioneer. The fact is, he built his career with the support and labour of others. ‘His’ Museum would not be here at all were it not for Amelia Blanford Edwards (1831–1892). So on International Women’s Day this year we celebrate our true founder .

Amelia Edwards was a gifted Victorian who knew many of the most creative minds of nineteenth-century England: she wrote ghost stories for Charles Dickens, exchanged long letters with the poets Dante Gabriel and Christina Rossetti, and received personal sketches from William Powell Frith. She was instrumental in establishing the Egypt Exploration Fund and her exhausting 1889-90 lecture tour of the North East Coast of US was celebrated not only for her scholarly command of ancient Egyptian history, but also for her stance on women’s suffrage and education. Needless to say I am a complete fan girl.

Hailed as a novelist, a traveller and an Egyptologist, Edwards already has two biographies in her honour. She has well-deserved entries in numerous compendiums of female explorers, including ‘trowelblazers’, and in a few weeks time English Heritage will unveil a blue plaque at one of her former homes.

What hasn’t been examined to any great extent, however, is Edwards’ identity as a collector. And she collected a lot. In her own words “dearer to me than all the rest of my curios are my Egyptian antiquities… I have enough to stock a modest little museum.” It is this precious assortment that formed the founding collection of UCL’s Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology.

The problem is that it is not clear how many artefacts were transferred to UCL in 1892. They were quickly subsumed within the swelling mass of material acquired by Flinders Petrie and his teams. So I’ve been spending a bit of time recently peeling back the layers of documentation in an attempt to locate things from her collection. Fortunately, I have a few leads.

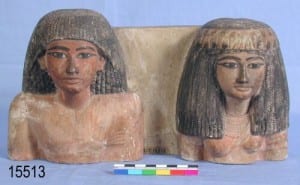

The first is Edwards’ own article, ‘My Home Life’, published shortly before her death. She estimated that she lived with “hundreds, nay, thousands” of items in cupboards, boxes and hidden behind books. For Edwards, each object “recalls the place and circumstances of its purchase, brings back incidents of foreign travel, and opens up long vistas of delightful memories”. All very cozy and nostalgic. But before we paint Amelia as an old romantic, it is also clear that some items hark back to her more macabre works of fiction: she described two heads of mummies in the wardrobe of her bedroom, which “perhaps, talk to each other in the watches of the night, when I am sound asleep”.

Most of the objects Edwards’ mentions are so numerous in the Museum today that it will be hard to locate them. One of her passing remarks, however, caught my attention: “…there is a somewhat battered statue of a Prince of Kush standing upright in his packing-case, like a sentry in a sentry-box, in an empty coach-house at the bottom of the garden.” Now there so happens to be just such a forlorn figure on the back stairs of the Museum that would fit the bill. Registered as ‘UC14701’, this anonymous statue has not fared much better since leaving Edwards’ coach house and, until last month, was precariously propped in a corner. Thanks to funding from the Friends of the Petrie Museum, however, a new mount for this lost ‘Viceroy of Kush‘ is being built.

No-one puts a Prince in the corner: UC14701, a statue of a ‘Viceroy of Kush’ before conservation and remounting.

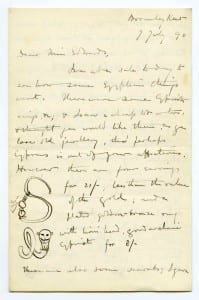

A second source for finding Edwards’ objects is the Museum archives. There is, for example, an old scrapbook of labels, the earliest list we have of the Egyptian collection at UCL. Also in the archive are a series of letters from Petrie to Edwards that, once the handwriting is deciphered, contain useful clues. Several regard relics Petrie bought for her in Cairo or discuss items recovered from the excavations he directed. One letter notes a collection of Egyptian antiquities bequeathed to her by Sir Erasmus Wilson, a distinguished medic. Wilson had a keen interest in Egypt and had funded the transport of ‘Cleopatra’s Needle’ from Egypt to the banks of the Thames.

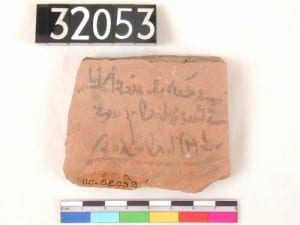

The third lead is Edwards’ best-selling book A Thousand Miles up the Nile. In her account of explorations on Elephantine Island, for instance, she records that: “…among rubbish heaps and bleached bones, and human skulls, and the sloughed skins of snakes, and piles of parti-coloured potsherds, we picked up several bits of inscribed terra-cotta”. On her return she wrote to the British Museum asking for information about these finds, which curator Samuel Birch identified as tax receipts. Putting two and two together allows identification of at least one of possible candidate (UC32053).

A pottery fragment with ancient Egyptian text written on it (UC32053). Sadly not ancient wisdom. Just a tax receipt from the late 1st millennium BC.

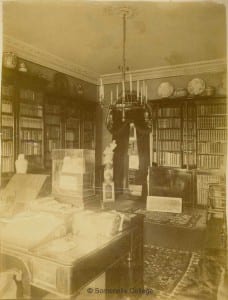

These letters are looked after in Somerville College, Oxford. Amongst the papers and watercolours held there is a photograph of Edwards’ study in which the unmistakable outline of UC15513, a sculpture of a woman and her husband, stands in front of her desk. In ancient times they would have been the focal point of a tomb chapel, awaiting offerings and prayers for their well-being. Amelia took over that role in the late nineteenth century and, today, they are cared for here at UCL.

Bit by bit, histories of Amelia Edwards’ collection are emerging. Some artefacts were discovered, others were excavated or purchased, while a few were inherited. Many still await rediscovery. The hunt for the collection within a collection continues.

2 Responses to “The Edwards Museum”

- 1

-

2

Clive Carter wrote on 10 February 2023:

Really great to see the work to credit Amelia making such progress.

Close

Close

How interesting to find out there was a woman behind the Petrie Museum, not to be confused with the petrie dishes of chemistry fare. Fantastic to note that there is a collection within a collection and there has been a lot collected! Great to see the work of more women around our campus. Well done Amelia, we remember you still. Well informed article. Thank you.