Specimen of the Week: Week 168

By Will J Richard, on 29 December 2014

Hello one and all! Will Richard, here again, wishing you a merry just-after Christmas and before New Year. I expect most of us are still recovering from the festive period. That magical time when friends and family come together in perfect harmony…

Hello one and all! Will Richard, here again, wishing you a merry just-after Christmas and before New Year. I expect most of us are still recovering from the festive period. That magical time when friends and family come together in perfect harmony…

Hmmm…

So, to keep it seasonal, last month I told you all about one of our closest friends (the dog). So this month I’ve got to take a look at some of our closest family.

And to start, let’s be honest. A family row is really part of the whole Holidays thing. We’ve all snapped while caught up in the stress-tivities, but then most of us agree to move forward for the sake of “the others”. But if it is the season to be grumpy, I think I’ve found the biggest family ding-dong ever.

Believe me….

This week’s specimen of the week is…

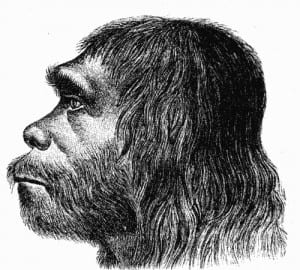

**The Neanderthal skull cast**

1) There’s one in every family

Homo neanderthalensis is an extinct species (I told you it was a big row) of hominid. They are believed to have lived across Eurasia for approximately 200,000 years, eventually becoming extinct about 40,000 years ago. The name “Neanderthal” comes from the site of their first discovery: the Neander valley. Pleasingly the valley is named for Joachim Neander, whose own name derives from the German “Neumann” or new man. The Neanderthal genome project found that 99.7% of all our genes were shared and some experts maintain that they were not a distinct species but rather a subspecies of humanity (Homo sapiens neanderthalensis), though this is disputed.

2) Who is this dude?

Our cast, sat at the bottom of Case 87, is modelled from one of the most celebrated of heads. The original was discovered in La Chapelle-aux Saints (France) in 1908 and is known colloquially as “the old man”. And he is. The skull has been dated to approximately 60,000 years ago. When he died, however, he was merely 40.

This “old” (I use old as a purely relative term) man has lost his teeth and has signs of advanced osteoarthritis. It has been posited that his degenerated condition is good evidence for altruistic care by the community, though others argue that enough of his dentition was in place to allow him to limp by on his own. Either way, we know he didn’t limp very far.

3) It’s definitely not a wonderful life!

As the battered state of our friend intimates, Neanderthal life was tough. 80% of all the individuals who survived into adulthood died before their 40th birthday. A study in 1995, examining the nature of the injuries and placement of fossils, speculates as to whether older individuals who could no longer keep up were abandoned. Not a very joyful thought. Infant mortality must also have been very high. Juvenile remains are found relatively commonly and are often fragmented and apparently discarded (in one case seemingly in the local rubbish pile). By necessity Neanderthals must have had a pragmatic relationship with life and death.

4) Family troubles

Recent analysis places the arrival of modern humans (us) in Europe approximately 5000 years before Neanderthal extinction. It seems almost unthinkable, therefore, that some degree of family tension did not arise. The replacement of one species by another is not unusual. The mechanism through which this took place is, however, disputed.

There must have been some competitive advantage. Violent genocide by an invading population of modern humans has been proposed. It is also possible that new contact with other species of hominids brought Neanderthals new diseases for which they had no immunity. Or climate may have played a part. We know that Neanderthals had clothes and that they were used to cold conditions. In the last Ice Age, however, the previously forested landscape of Europe was replaced by sparsely vegetated, semi-arid steppe. This caused the larger prey items (mammoths, bison and deer) to flee south and so deprived the Neanderthal population of a key food source. Neanderthal communities are thought to have lacked the social organisation and hunting technology to adapt to this. Modern humans, however, had the behavioural flexibility to move towards agriculture and weather the storm.

5) Love not war

Some academics maintain that Neanderthals never became “extinct” as such, but were rather absorbed into the general human population in a process known as hybridization. Modern Asians and Europeans carry between 1% and 4% Neanderthal DNA. We know that interbreeding did take place and so perhaps the essence of Neanderthal lives on.

Judging by my family this Christmas, I certainly think so…

References:

Dawson, J and Trinkaus, E; 1997; Vertebral Osteoarthritis of the La Chapelle-aux-Saints 1 Neanderthal; Journal of Archaeological Sciences; V 24. 1015-1021

Tappen, N C; 1985; The dentition of the “old man” of La Chapelle-aux-Saints and inferences concerning Neandertal behavior; American Journal of Physical anthropology; v67; 43-50

Pettitt, P.B; 2000; Neanderthal lifecycles: developmental and social phases in the lives of the last archaics; World Archaeology; v31; 351-356

Gilligan, I; 2007; Neanderthal extinction and modern human behaviour: the role of climate change and clothing; World Archaeology; v 39; 499-514

Will Richard is Visitor Services Assistant at the Grant Museum of Zoology

One Response to “Specimen of the Week: Week 168”

- 1

Close

Close

LOVE the Santa hat! My son was delighted with his membership as a Christmas present (and adoption of an olm) – I really recommend it as a gift for any science/zoology-minded person!