Through the Looking Glass Sponge

By ucwaemo, on 18 November 2014

Since joining the Museum as artist in residence last month, I’ve spent a lot of time looking through glass. I’ve looked through the plate glass cabinets protecting the specimens, the thickly blown glass of the specimen jars, and finally the specimens themselves: glass sponges. These creatures are 90% silica, formed of threads of glass spicules. They are usually found in the dark depths of the ocean, but up in the spotlights of the Museum they glow – a bright shelf of organic glass. Their structure is so intricate that I have to use even more layers of glass to be able to see them: reading glasses, magnifying glasses, and my recently acquired endoscope (excellent for getting round those awkward sponge corners). With all these layers of glass, reflection becomes an issue – in photographs, my face or the camera lens can appear, and viewed at certain angles even the specimen seems to be looking at its own reflection within the glass jar.

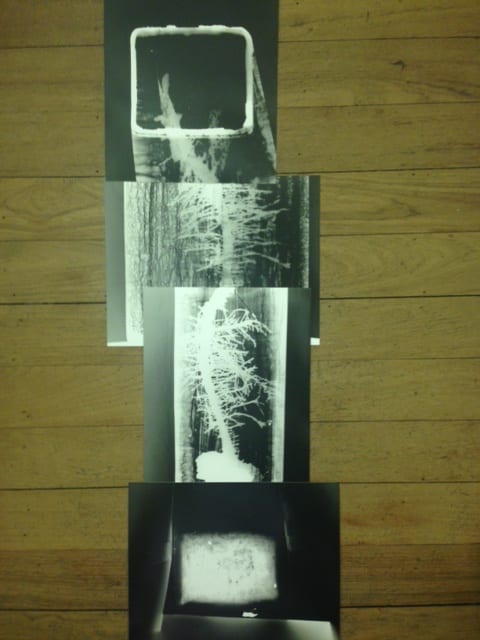

Last week I put together a pinhole camera for one of the specimens. Pinhole cameras are made of a light-sealed box with photosensitive paper inside, and a small pinhole on the opposite side. The pinhole acts like the shutter of a camera – you aim the pinhole at whatever you want to capture and the light travels through the pinhole to the photosensitive paper inside the box, which is then developed in the darkroom and the image appears. I wanted to try putting the specimen inside the pinhole camera, with photosensitive paper surrounding it. I hoped that by doing this I would get a 360 degrees photogram of the glass sponge. However, the glass sponge and its jar had other ideas.

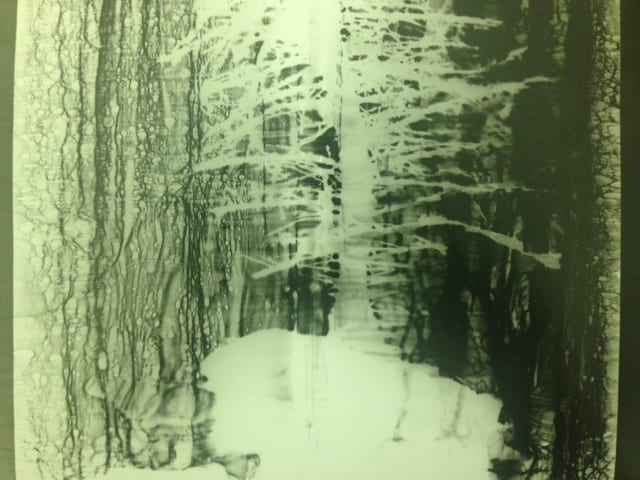

Here are some photograms I took of the Museum’s Walteria leuckarti.

The shape of the sponge itself is like a winding, thorny spine, but what I didn’t expect was the effect of the glass jar. The variations of thickness in the blown jar are virtually invisible when viewed normally – your focus is usually on the specimen inside. But once light is shone through it, the jar has a chance to make its mark: wavy lines and bubbles appear, as if for a moment the sponge were back in its watery home. What excites me about these images is that they begin to capture how the same material of silica can be organic and inorganic. Depending on our focus, these glass objects can be both looked at and looked through.

Eleanor Morgan is Artist in Residence at the Grant Museum of Zoology

One Response to “Through the Looking Glass Sponge”

- 1

Close

Close

Originally trained in chemistry I always marveled at these glass “sponges”. Because while it is easy to appreciate how e.g. corals could form a calcified skeleton, to “secrete” pure silica (of which the most inert test tubes are made …) is a matter that a chemist would find challenging, let alone a sea creature close to freezing point as the depths of the oceans usually are due to the physical anomaly of water. And other than calcium carbonate which is opaque at best, silica structures (for their hardness as well as transparency are “the next best thing” to organic “diamonds”.