Divorce, Adultery and Revenge: an alternate Valentine’s Day

By Edmund Connolly, on 14 February 2014

Valentine’s Day can be an arduous 24 hours of franchised affection and a reminder that being single is not socially commendable. To play the merry dissenter, and offer those of you who are not a fan of the day, I will celebrate 4 archaeological heroes who flew in the face of Valentine’s lucid message and offer a far more commendable representation of love.

Valentine, the Man.

A 3rd century saint, Valentine is a tricky man to track; his name does not appear in the earliest martyr lists, however he does appear in Pope Gregory XII’s rather lengthy read Roman Martyrlogy produced in the 16th century.

Many stories involve Valentine restoring the sight of a blind girl, before being martyred for his faith. Likewise, Valentine is often associated with marrying Christians, the Nuremberg Chronicle suggests he was marrying a couple when caught and martyred, perhaps explaining his association with lovers and the element of a secret love.

Nowadays, much of this hazy history is forgotten and Valentine is an excuse to drink champagne, receive roses and write love poems. Despite having the emotional range of a salad fork, even I feel there are perhaps some better advocators of love, so present 4 Petrie Paramour Paragons.

Ishtar (Astarte)

The goddess Ishtar is a good example of multicultural Ancient Egypt, being an Assyrian deity who was immensely popular across the Mediterranean and represented in this 19th Dynasty scarab.

A goddess of love and fertility she was hardly a blushing valentine, also being the goddess of war and justice. It’s a common misnomer that Astarte (the Greek name for Ishtar) equates directly to the Greek Aphrodite (Goddess of love) or Artemis (Goddess of female power and hunting). In truth she is both of these goddesses, being a beautiful paramour but you certainly wouldn’t mess with her. In fact, Ishtar is an ancient bunny boiler, taking revenge on any man foolish enough to wrong her (The Epic of Gilgamesh 88).

Love Scale: 8 / 10 (numerous lovers, popular across the med, but still a vengeful ex).

Divorce Ostraca

Ostraca are found in a host of Egyptian sites, this one comes from Thebes, an ancient city in what is now Luxor.

This Ostraca details a divorce between a husband, Hesysunebef, and is wife Hel in the 12th century BCE. Divorce was not that rare an action and it certainly was not necessarily biased towards the husband; a woman could keep her dowry following divorce, and there existed legal frameworks to govern the procedure (Theodorides 1975:284).

Divorce may not be the most loving of actions, but following the divorce the husband continued to provide his wife with a monthly amount of grain for three years, helping her to support herself following the separation.

Love Scale: 6/10 (Pity their marriage didn’t work out, but nice to see they were on grain giving terms)

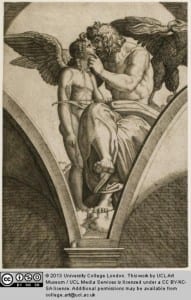

Berenice II

Egyptian Queens called Berenice or Cleopatra are inevitably from the Ptolemaic era and most probably murdered a member of their family at one point or another.

Berenice II was the Great-great-great-great-great grandmother of Cleopatra VII (she of Shakespeare and Elizabeth Taylor status). Berenice was married to Demetrius the Fair, a Prince Charming from Macedonia. However, this marriage went quickly awry with Demetrius having an affair with Berenice’s mother Apama II. Berenice discovered the couple and killed her husband in a jealous rage, the story was then documented by the love-bard Catullus.

Love Scale: 7/10 (a royal international couple with stunning good looks, points deducted for the murder and adultery)

Flinders Petrie

Flinders Petrie married Hilda Urlin in 1896, despite his father’s original misgivings. In a charmingly understated wedding the Petries were married in Kensington with a full turn out from Hilda’s family, but Petrie had only his friend, Flaxman Spurrell as best-man present. Despite the slighted wedding the Petries set off on their honeymoon, only to endure one of the worst storms on the channel for years so their boat was delayed and they had to spend the night, wet and cold, in Dover.

However, when they finally reached Egypt Hilda was enchanted, writing that she could not believe, “Egypt could be so Egyptian” (Drower, 95, 239). Despite their rocky start Flinders and Hilda were married for nearly fifty years and had two children, John and Ann.

Regardless of the understated wedding, family slights and rocky honeymoon, the Petries were in love. Flinders wrote to Hilda:

“To have this new duty of pleasing you, and making all things as bright as I can for you, will I know be the very best thing for my own life. How we will rake all through Cairo, and raid about that Eastern desert!” (Drower, 1995,236)

Love Scale: 9/10 (long marriage, flying in the face of family misgivings and cross-continent love).

Happy Valentines Day, One and All.

Edmund Connolly is the British Council – UCL Museum Training School coordinator .

Close

Close