Science Research in a Science Museum?

By Mark Carnall, on 30 May 2013

As chance would have it at the same time as we received research interest from the Royal College of Art, colleague Dr Zerina Johanson, researcher in the Earth Sciences Department at the Natural History Museum, had also contacted me about our paddlefish specimens. We have less than a dozen paddlefish specimens in the Grant Museum (fish is the family Polyodontidae, represented today by only two species the American paddlefish Polyodon spathula and the possibly-extinct Chinese paddlefish Psephurus gladius) and fortunately, one of these specimens, matched the specifications for research (in this article I wrote about how ‘usable’ specimens dwindle to tens from thousands depending on the type of research).

So for the second time in May I was on bodyguard duty to escort one of our specimens down to South Kensington for some scanning, this time for SCIENCE!

Here’s the specimen I was escorting and isn’t it a beaut? The most distinctive thing about these fish is the ‘paddle’ which is one of the most beautiful skulls in the animal kingdom and as with our American paddlefish specimen, the paddle-like rostrum starts off longer than the rest of the animal. The paddle contains electroreceptors and it is thought that this is used to detect zooplankton which these filter feeders pick out of the rivers they live in. Paddlefish can grow up to 2m long but for research purposes Dr Johanson needed specimens that would fit inside a CT scanner. The paddle may be what gives this fish its common name but it wasn’t the paddle that Dr Johanson was interested in, instead her research is into the teeth of these animals.

Paddlefish are ‘primitive’ ray finned fish. In this context primitive doesn’t mean that these animals are somehow simply constructed but they haven’t changed a great deal over geological time. It’s easy to confuse primitive with old or outmoded but many of the animals we call ‘primitive’ have some highly derived adaptations that have put them in good stead for tens of millions of years. Because paddlefish are a primitive group, Dr Johanson is interested in how paddlefish grow (and lose) their teeth. Animal teeth are fascinating and across the animal kingdom there are a myriad of different ways that teeth are specialised for a variety of functions including of course feeding but also grooming, grinding, hooking and spearing. As interesting are the different reasons behind why lots of animals have completely lost their teeth through evolution including baleen whales, turtles, birds, sucking ichthyosaurs and all those mammals specialised for eating insects including echidnas, anteaters and pangolins. Paddlefish lose their teeth throughout their life and it is thought that by comparing how paddlefish go gummy and looking at gene expression from other fish that ‘lose’ or modify their teeth like sharks and pufferfish we can get some insight into the evolution of teeth and tooth replacement with possible implications for human teeth.

If you remember anything from GCSE science classes, in order to test a hypothesis you need to have a high sample number to reduce errors and outliers that might skew the data. This is where our humble specimens comes in. Paddlefish specimens are rather poorly represented in museum collections and Dr Johanson has been contacting a number of museum collections to image paddlefish. The research is supported by the Natural History Museum Image and Analysis Centre, and colleagues Farah Ahmed and Dan Sykes who work at the centre met us in the bowels of the museum to scan our specimen. Here’s the Grant Museum specimen being scienced.

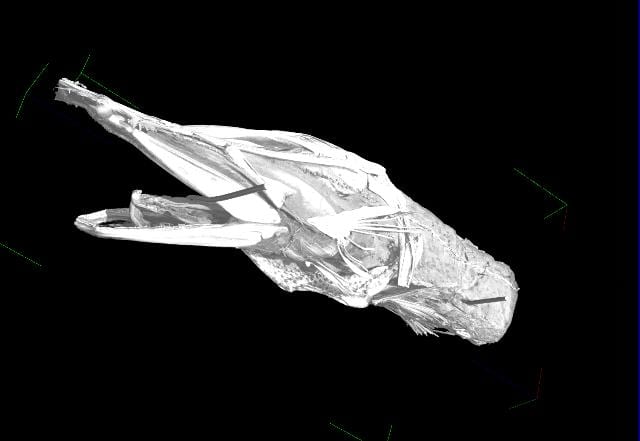

From the CT scan a three dimensional virtual model built up from serial x rays through the specimen, models can be created and analysed, compared and contrasted to other samples to try to work out how paddlefish grow and subsequently lose their teeth. With a series of CT scans like the one of the Grant Museum specimen represented in the screenshot below, individuals can be analysed and compared without having to constantly reference (or dissect) specimens in museum collections.

Reconstructed CT scan of the Grant Museum paddlefish put together by Dan Sykes Natural History Museum Image and Analysis Centre

Dr Johanson’s research continues, whilst we were there another six specimens were prepped ready to be processed that same day and I look forward to what the scans show and how this specimen has contributed to what we know about paddlefish. Hopefully this mini series of posts demonstrate why museum collections are important in both art and science and how specimens don’t just sit inside cases waiting to be dusted every now and then.

Mark Carnall is the Curator of the Grant Museum of Zoology

Close

Close