Specimen of the Week: Week Seventy-Nine

By Emma-Louise Nicholls, on 15 April 2013

I feel that we know each other well enough now for me to get personal. I am going to share a story about my sister. Today, she is flying back from the Sahara desert where she has just completed the Marathon des Sables; widely acclaimed to be the ‘Toughest Footrace on Earth’. It consists of no less than six marathons in six consecutive days, up mountains, over sand dunes, and across the desert, all whilst carrying a 10 kg pack. In tribute to what must be the singly most impressive thing anyone I know has ever achieved, I’m going to dedicate this week’s specimen to her and tell you about another type of bird that has the ability to run huge distances in the African desert. This species can reach up to 70 kilometres per hour and has such incredible stamina that it can maintain a speed of 50 kilometres per hour for over 30 minutes at a time. This week’s Specimen of the Week is…

I feel that we know each other well enough now for me to get personal. I am going to share a story about my sister. Today, she is flying back from the Sahara desert where she has just completed the Marathon des Sables; widely acclaimed to be the ‘Toughest Footrace on Earth’. It consists of no less than six marathons in six consecutive days, up mountains, over sand dunes, and across the desert, all whilst carrying a 10 kg pack. In tribute to what must be the singly most impressive thing anyone I know has ever achieved, I’m going to dedicate this week’s specimen to her and tell you about another type of bird that has the ability to run huge distances in the African desert. This species can reach up to 70 kilometres per hour and has such incredible stamina that it can maintain a speed of 50 kilometres per hour for over 30 minutes at a time. This week’s Specimen of the Week is…

**The Ostrich Skull**

1) The ostrich, in case you lacked all forms of children’s books on natural history when you were growing up, is the largest bird of our time. By ‘our time’ I am taking the leap of faith that none of you are over 700 years old and thus are not temporally acquainted with the moa. The ostrich is both the tallest and the heaviest modern bird species, and can reach up to an intimidating 2.8 metres in height, and 160 kg in weight.

2) Males and females can be easily told apart. Females are more brains than beauty and only come in grey, easily distinguished from the mesmerisingly monochromatic males that have black bodies, white wing and tail tips and pale necks and legs. Juveniles of both sexes typically resemble the females in appearance. The ostrich’s colouring helps them blend in with the open, semi-arid plain habitats, that range from desert to savanna. The male uses his good looks to attract the female in a lovely dance display of head dropping, shaking each wing alternately, and tail bobbing. As with any human male that wants something, he also tends to stamp his feet.

A female ostrich incubating her eggs in

the Serengeti, Tanzania. (Image taken by

Joachim Huber. Image taken from

commons.wikimedia.org)

3) Why can’t an ostrich fly? Believe it or not, the answer is not simply “they’re too flippin’ big”. Well it sort of is, but they also lack some other compulsory requirements. Most poignantly, they don’t have flight feathers. An ostrich feather lacks the tiny hooks that in a flight feather would hold the barbs together into the equivalent of a kite sail. As a result, the ostrich takes on a rather fluffy (cough*scruffy*cough) appearance, rather than the sleek, well groomed effect of say a duck or an owl.

4) Another fun pub-quiz-winning ostrich fact is that it is the only bird species to be numerically digitally restricted. In so much as, it is the sole species of bird with only two digits on each foot. The inside toe of each foot is absolutely ma-husive, and comes with a Velociraptor style ten centimetre long claw. The thing of nightmares, this claw is used for defence, along with the ostrich’s ability to deliver a stomach smashing, high pitched voice inducing, kick… if they so desire.

4) Another fun pub-quiz-winning ostrich fact is that it is the only bird species to be numerically digitally restricted. In so much as, it is the sole species of bird with only two digits on each foot. The inside toe of each foot is absolutely ma-husive, and comes with a Velociraptor style ten centimetre long claw. The thing of nightmares, this claw is used for defence, along with the ostrich’s ability to deliver a stomach smashing, high pitched voice inducing, kick… if they so desire.

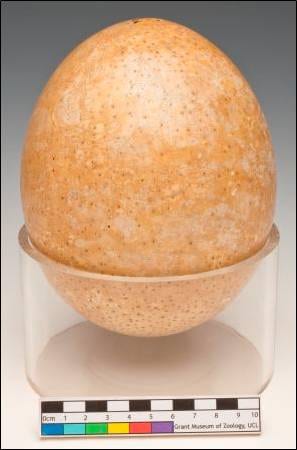

5) I have one final mind-blowingly superb ostrich fact for you before I sign off. All organisms are made up of cells. Biology 101. An unfertilised egg, as you may know, is considered a single cell. The ostrich egg therefore, being a not-insignificant 16 cm in length and 1.5 kilograms in weight, is the largest single cell in the world! Until the male gets near it and the fertilisation process ruins the mono-cellular-ness. Baby ostriches are darn tootin’ cute, with stripy necks and a mop of red hair. Adult ostriches are good parents and will defend their chicks, and other’s chicks too, from threats such as lions which FYI, can be killed with the power of a kick. You could say their defence mechanism is a roaring success.

Emma-Louise Nicholls is the Museum Assistant at the Grant Museum of Zoology

Close

Close