A Tale of A Whale

By Simon J Jackson, on 19 October 2012

Earlier this year Mark Carnall, the Grant Museum Curator, and I uncovered a whale in our collection — well, actually the ‘long-dead’ skeleton of a whale. Initially, we were confronted with boxes of huge vertebrae mixed with ribs — specimens several times the size we are used to dealing with. After putting our detective caps on, we ascertained that most of these bones belong to the same animal as does the huge skull we have in our balcony collection area in the Museum. Going back to the historical records, there is an interesting story behind this specimen, which I thought would be nice to share with you …

The story starts in Weston-super-Mare on the Somerset coast of the Bristol Channel on Wednesday, 7 November 1860 when a fishing expedition trekked out to sea in pursuit of “two great fish” — a scene which was described in the annals of the town as one of its most exciting and extraordinary events. One of these fish — well, it must be clear now to the boatman that these were actually whales — made off into open water, but the second became involved in a great fight, and, sadly, its last. After more than 20 rounds were fired upon it, it tragically succumbed to its inevitable fate (as a museum specimen), and was towed to Knightstone. Here, all 26 feet and 6 inches of this Northern Bottlenose Whale (Hyperoodon ampullatus) were exhibited in a tent where everyone flocked to see it.

The next part of the story picks up in Bristol, where the new specimen was transported to and displayed, drawing in crowds from around the city. “Whales Shares” were put up on offer and Mr Edward Goodingham purchased the specimen from two of the boatman for £120. The specimen was to be stuffed and displayed across the kingdom. However, this end for the animal was not to be and in fact the whale started to decompose immediately — perhaps the animal’s act of final indignation. Confronted with this awful stench, Mr Goodingham was faced with the prospect of a total loss, apart from the £18 for the oil and £5 offered for skeleton.

Returning full circle, the specimen ended back at Weston-super-Mare where it was eventually sold to Mr Mable. The specimen was buried in the ground for two years leaving insects and bacteria to do the dirty work of cleaning the bones. To finally polish them, Mrs Mable then boiled the bones one by one.

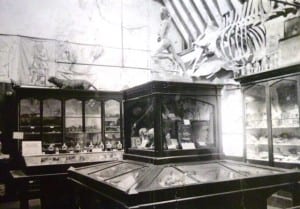

Photograph of the whale skeleton (top right) on display. Photograph from Woodspring Museum, Weston Super-Mare

Photograph of the whale skeleton (top right) on display. Photograph from Woodspring Museum, Weston Super-Mare

The specimen was wired together and became a popular exhibit at the Weston-super-Mare Museum, until its big reorganisation in 1948 when it was sent to University College London. There it lurked among several boxes and locations before being unpacked, documented and repackaged in our off-site storage facility this year (2012).

You can get a sneak peak of the whale under cover as featured over at the Daily Mail photo article.

2 Responses to “A Tale of A Whale”

- 1

-

2

Help us build and clean a whale skeeton | UCL Museums & Collections Blog wrote on 3 July 2017:

[…] The specimen’s story begins in 1860 when it was originally collected in Somerset, when an expedition set off across the Bristol Channel in pursuit of “two great fish” (as they were described by the local newspaper – whales are, of course, mammals) – one of which was brought back to land. After a period “on tour” as a whole carcass, the prepared skeleton was displayed hanging from the ceiling of the Weston Super-Mare Museum. It eventually came to the Grant Museum in 1948, but it had been dismantled into its separate bones. (Its full, remarkable story, including the use of entirely inappropriate whale-murdering equipment, misguided entrepreneurship, rancid carcasses, financial ruin, and the unusual tasks the wife of a 19th century curator might find herself doing, can be read in a previous post). […]

Close

Close

Good post. I learn something totally new and challenging

on blogs I stumbleupon every day. It will always be interesting to

read through articles from other writers and practice a little something from their websites.