Specimen of the Week: Week Fifty-Three

By Emma-Louise Nicholls, on 15 October 2012

After the excitement of the blogs of the last two weeks (I found them exciting), I thought this week I should tone it down a bit and write about an animal that is considered a little more run of the mill, and less out of the ordinary. Then I thought, stuff that for a silly idea, I’m going to present to you the most exciting object I have in my field of view from the front desk, which is where I was at the time. By pure coincidence, it just so happens to also be one of my top five specimens out of all 68,000 currently held at the Museum, which I think is introduction enough, and so- this week’s Specimen of the Week is…

After the excitement of the blogs of the last two weeks (I found them exciting), I thought this week I should tone it down a bit and write about an animal that is considered a little more run of the mill, and less out of the ordinary. Then I thought, stuff that for a silly idea, I’m going to present to you the most exciting object I have in my field of view from the front desk, which is where I was at the time. By pure coincidence, it just so happens to also be one of my top five specimens out of all 68,000 currently held at the Museum, which I think is introduction enough, and so- this week’s Specimen of the Week is…

**The Blue Sea Slug**

Bare with me.

1) I think that the first, non-subjective fact, that we should learn about this species is just how gosh darn attractive it is. A completely objective statement, I’m sure you will agree. If I had to turn into a slug, but in compensation got one wish, my wish would be to turn into this one. Erm, or maybe I would wish to remain human?

2) The blue sea slug floats about upside down. No, not because it gets off on head rushes. Actually it is not clear why they do this so it may indeed be for that reason. But I feel it somewhat more probable that it’s due to the placement of the stomach, in which lies a gas bubble. Most irritating and occasionally embarrassing to us humans, the blue sea slug relies on a gas bubble in the stomach for flotation. Now I feel like conducting a study on which flavour curries for dinner keep you the most buoyant the morning after.

3) The beautiful colouration of the blue sea slug is for camouflage. The underside which is always on top, is blue or blue and white. The top side, which is always underneath, is silvery grey. Confused? Basically, to camouflage itself from predators such as sea birds that attack from above, the slug puts its blue side on the surface of the water to camouflage it with the surrounding sea. To camouflage itself from predators such as fish that attack from below, it puts its silvery grey surface pointing down to blend into the brighter sky above.

4) Not just your average common old slug- the blue sea slug is POISONOUS. OH YEAH. They are not naturally poisonous, they feed (primarily) on man-o’-wars (or should it be men-o’-war?) which are poisonous. They are actually, apparently, able to differentiate between the stinging nematocysts, and will select the most potent. They store the venom in sacs called cnidosacs. The result of concentrating the most potent of man-o’-wars toxin into small areas is that the stinging cells in the blue sea slug are more toixic, and more painful to humans, than a man-o’war itself. Neat.

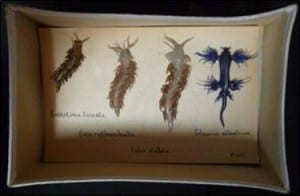

5) The blue sea slug at the Grant Museum is actually made of glass in an intriguing story of mystery and days of old…

Leopold Blaschka and his son Rudolph were descended from a long line of Czech artisans. They began their careers as jewellers in the mid 1800s in Germany. Museums of the day commissioned the family to make glass models of, amongst other things, marine invertebrates, as their soft bodies made them too hard to preserve. The mystery is that, how the Blaschkas made these exquisite, finely-detailed models is unknown, as their skills and secrets died with them in the 1800s. Most interestingly, no-one has been able to repeat their work in the modern day using the tools that were available at the time. Strange. Witchcraft perhaps?

Emma-Louise Nicholls is the Museum Assistant at the Grant Museum of Zoology

Close

Close