Trapped in the desert – part one

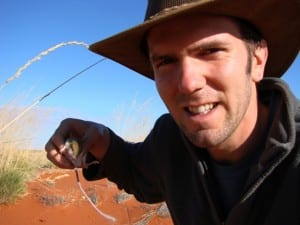

By Jack Ashby, on 10 March 2011

From April 2010 I spent about five months undertaking several zoological field projects across Australia. I worked with government agencies, universities and NGOs on conservation and ecology studies ranging from Tasmanian devil facial tumour disease, the effect of fire, rain and introduced predators on desert ecology and how to poison cats. This series of blog posts is a delayed account of my time in the field.

Week Eight

Having spent the last month in the cool temperate rainforests, alpine highlands and green misty sclerophyll forests of Tasmania working on devil facial tumour disease fieldwork, it was going to take some adjusting to the climate I was expecting camping in the middle of the Simpson Desert. Fortunately it wasn’t a sudden change as it took three days for the team from the University of Sydney to reach camp, 2400km northwest, nearly halfway up the border of Queensland, and the Northern Territory.

Our convoy of 4x4s was carrying fourteen people working or volunteering for the Desert Ecology Research group at Sydney, plus their food and equipment for three weeks, spades. Their base, “Main Camp”, was in truth a crumbling caravan between two dunes in a stand of gidgee trees, which smell like sulphorous popcorn. The caravan was the storeroom. We dug a fire pit as a kitchen, beds were either in swags or tents. The bathroom was over the dune. If the dune was occupied, one of two pink lengths of flagging tape were tied in a knot, to let others know which side – left or right – should not be disturbed. The Simpson Desert is home the world’s longest parallel dune system (check out a satellite view on google), so the view from the top of a high dune is a genuinely stunning place to spend alone time.

Chris Dickman and the research group he runs have been visiting this area three or four times a year for the last twenty years, making it one of the best long-range ecological studies in the world. They study the effect of different factors on the animals and plants that live here in the sand. Expectations were high because a few months before there had been a massive amount of rain and the desert as we saw it had massive patches of green.

A few years ago, partly as a result of the research the University of Sydney have done here, the conservation NGO Bush Heritage bought two of the three cattle stations that the study is carried out on here. To my mind, a desert is a pretty terrible place to raise cattle, but they do. There’s not much other work for locals to be had here. Since then the Reserve Manager here has been pulling out fences and restoring it to it’s former habitat.

In future posts I’ll talk about what the science was – in brief we were looking at the effect of rain, fire, introduced predators and cattle on native animals and plants. This is the technique:

We drove off in teams for four days at a time to different sections of the massive study site. On the first day we set the traps, and check them for the next three days. We were using pitfall traps aimed at catching small mammals and lizards. They are 60cm long pipes dug straight down in the ground, halfway along a 10m long drift fence. As animals go wandering about their business, they hit a fence and follow it. If they turn the right way they’ll reach the pit and fall in. The pits were arranged in 100m grids of 36 traps, and every morning (before they get hot and cook) we would empty them of animals. Small lizards can bury themselves in a couple of millimetres of sand, so it all needed to come out (which isn’t easy in a desert with big sand drifts). Small mammals – carnivorous rodents (mostly dunnarts, mulgaras and ningauis) and native rodents (mostly hopping and other mice) and large lizards are retrieved by putting your hand inside a canvas bag and pushing your hand down the tube to grab them at the bottom, without them climbing up your arm and escaping.

Generally I prefered to find the scorpions in the pile of sand I’d just scooped out with my hand, rather than seeing them at the bottom of the trap and have to think my way around getting them out.

All animals were given an ID by clipping their ears (mammals) or toes (lizards) in a set formula, to see how far they range if re-trapped, and measured in many ways, including reproductive status, before being released.

Next week I’ll talk about what we found, predator monitoring and excluding, and spot-lighting from the roof of a moving truck driving over sand dunes at top speed.

UPDATE: PART EIGHT HERE

2 Responses to “Trapped in the desert – part one”

- 1

-

2

UCL Museums & Collections Blog » Blog Archive » Sympathy for the devil – part three wrote on 2 May 2011:

[…] UPDATE: PART SEVEN HERE […]

Close

Close

[…] Last week I went through the tactics for trapping small animals in pitfall traps in the Simpson Desert where I spent a month with the University of Sydney’s Desert Ecology Research Group. This week I’ll talk about some of the other things that we did while we were there. […]