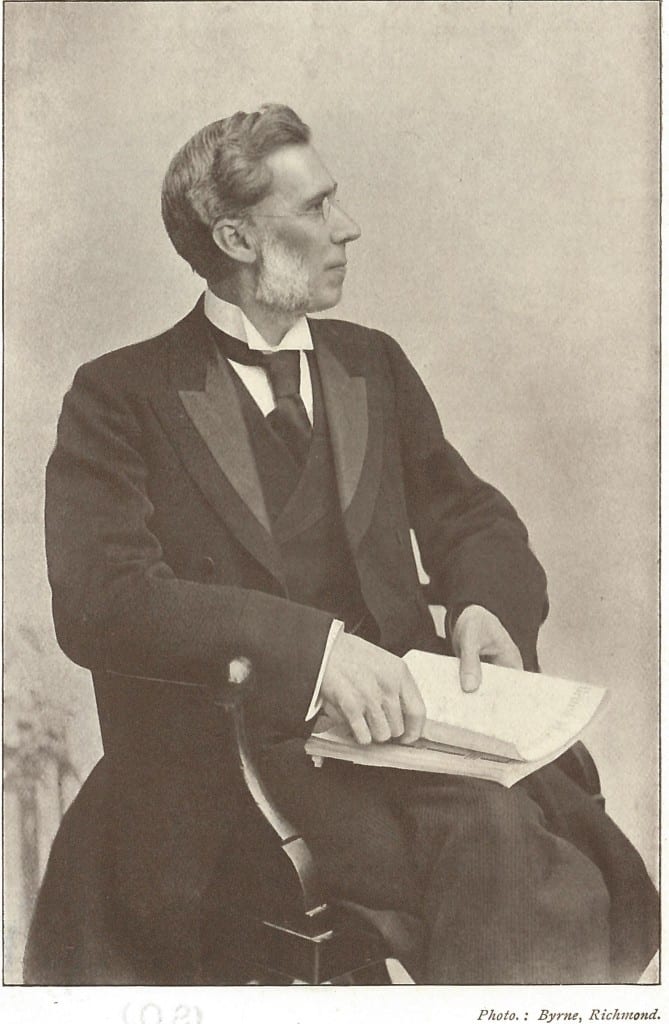

“I think I am as devoted to and I hope I have been as as successful in promoting the oral system as any one living.” Dr. David Buxton

By H Dominic W Stiles, on 10 February 2017

Dr. David Buxton (1821-1897) was a teacher of the deaf at Liverpool. He was co-founder of The Quarterly Review of Deaf Mute Education, an important publication that pre-dated the foundation of the National Association for Teachers of the Deaf and its journal, the Teacher of the Deaf, and spent the last years of his life working as secretary then Superintendent to the Manchester Adult Deaf and Dumb Institute. He was also a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature.

Buxton was born in Manchester, son of Jesse, a cotton spinner, and his wife Ann. On the Manchester baptismal register he was one of 64 children baptised on Sunday the 17th of June, 1821 (see records on ancestry.com). His obituary in The British Deaf Monthly, from which much of the following comes, says, “Of his early life we know little until his twentieth year, when he became an inmate of the Old Kent Road asylum, remaining there ten years, at first as junior, and ending as head assistant teacher.” According to his evidence to The Royal Commission on the Blind, the Deaf and Dumb, he started his teaching career at Old Kent Road in January 1841, and went to Liverpool in October 1851 (page 309. paragraph 9183 in the Minutes of Evidence). From there he moved to Liverpool as headmaster, where he remained for 26 years. Branson and Miller (p.194) tell us that Buxton joined the Old Kent Road Asylum “on the recommendation of the Reverend Alexander Watson of St. Andrews Ancoats, a relative of Dr. Watson whom he had met through a mutual interest in literature.” Unfortunately they give us no source for that statement. Alexander Watson was in fact a son of Dr. Joseph Watson by his second wife, Susannah Littlewood (thanks to @DeafHeritageUK for pointing that out).

In 1878 David Buxton became Secretary of the Ealing Teacher Training College, and was consequently on good terms with the oralist, Sir Benjamin Ackers. Ackers was one of the members of the Royal Commission. In his evidence to the Royal Commission of 1886, Buxton said (p.309), “I think I am as devoted to and I hope I have been as successful in promoting the oral system as any one living.” In paragraph 9179, he explains “My own special duty at the Old Kent Road was to teach the first class; I taught all to speak as it was called then, teaching them articulation.” Further on in his extensive testimony, which continues for over twelve pages of dense text, he was asked, presumably by the chairman of the committee for that session, Lord Egerton of Tatton,

We have three systems of teaching the deaf and dumb: the sign system, the combined system, and the oral system. Do you think that any one of those is so superior to the others that the State ought to insist that only should be taught; or do you think that there must be two or more systems recognised side by side by the State?”

He responded,

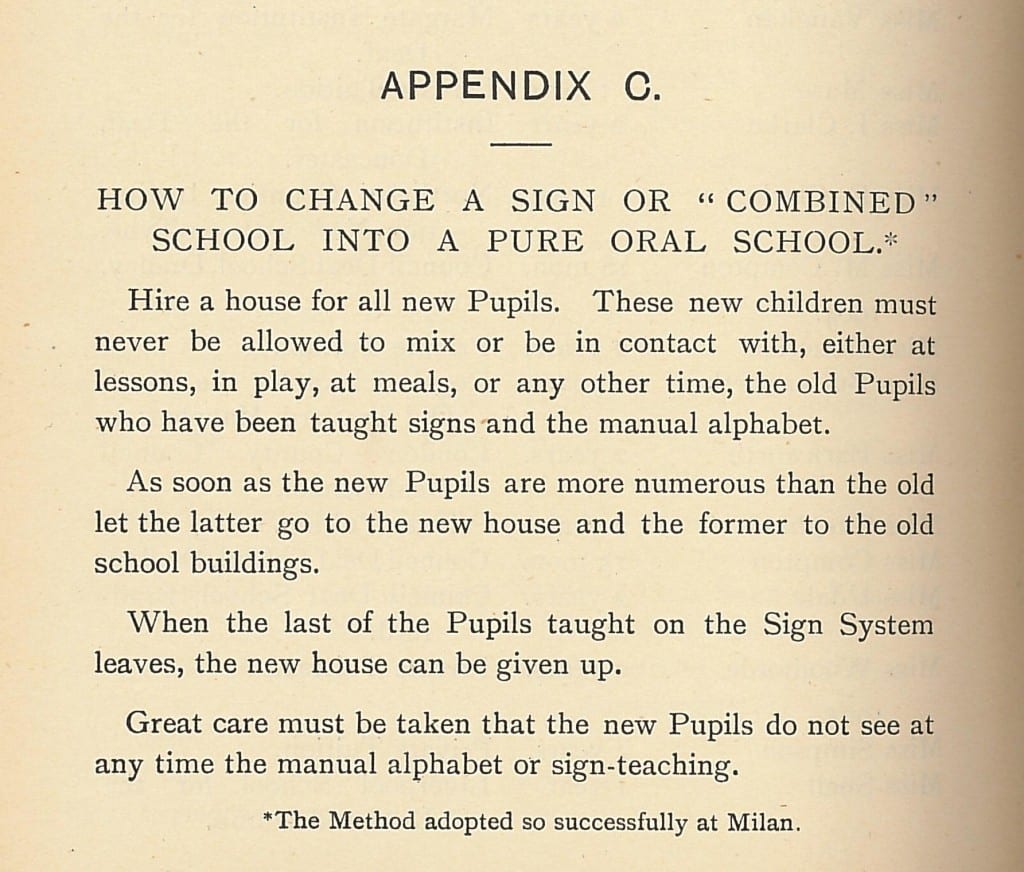

“I am so thoroughly in earnest in my advocacy of the superiority of the oral system, that I should be very glad to see every other extinguished; but I know that must be a matter of time. The oral system is incomparably the best; it is not open to question at all, because it assimilates the deaf to the class with whom they live. If I want to communicate by signs to a deaf child I have to descend to his level: but by the oral system I endeavour to raise him to my level. For a time perhaps the combined system may struggle on: I think that is very probable; but that the sign system in itself will last I have not the slightest expectation. I think it will die out. (paragraph 9221)

Some might say it is “an unconscionable time dying.”

On a curious note, in paragraph 9255 (p.314), he is asked about encouraging games such as cricket and football in school, and tells the commission, “One of my pupils at Liverpool came from Chester; he came to Liverpool to school to save himself from being drowned in the Chester Canal, I expect, for they could not keep the fellow out of the canal; he was in all day long on a summer’s day.”

The whole report is very long, but reading snatches of it brings the period to life, being reported speech, and I imagine, accurately recorded as an official report. This exchange is very illuminating:

9262. […] when I first became a teacher the very large proportion of those who taught in the institutions were deaf teachers.

9263. That is objectionable, is it not? – Most objectionable. When I went into the Old Kent Road Asylum, I think the staff was 12; I was the third who who could hear and all the other nine were deaf. They were very good specimens of what the combined system could do; most of them could speak; they all made signs to their pupils and to one another, but nearly all spoke to us, the hearing staff. Now I think deaf teachers are almost obsolete […]*

Buxton’s degree of 1870 was a rare honour, conferred on him, Harvey Peet, William Turner, and Charles Baker, by Edward M. Gallaudet (American Annals of the Deaf, 1870, p.256). It illustrates how influential his various articles were in the years before the Milan Congress.

In the Rev. Fred Gilby’s memoirs (p.149) he recalls Buxton :

I remember that Dr. Buxton was living, an extra-pure oralist though he was in theory, he ended up his days by acting as missionary to the deaf, and was acting as such in 1895 when I got there. A foremost champion of pure oralism, he was polite enough to come and lunch with me and to honour me with his company. He was a master of pure English but “how are the mighty fallen”, and he was now “preaching to the deaf on his fingers!” Sunday after Sunday in his old age he came to be using the method he had for a number of years been cursing up hill and down dale.

Buxton died of influenza on the 23rd of April, 1897, and was buried at Smithdown Road Cemetery, Liverpool. Ephphatha‘s editorial for June, 1897, says,

Many regarded him as the Nestor of our cause. He undoubtedly possessed a vast store of knowledge and a ready pen and tongue. But he did not prosper in a worldly sense. His life was beset with difficulties, with thorns and trials, yet he worked bravely on, good natured, patient, and scholarly unto the last. Let him be remembered for the good he did, and for the strenuous service of his seventy years.

American Annals of the Deaf, 1897, Volume 42 (4), p,269-70

Branson, J. & Miller, D., Damned for their Difference: the Cultural Construction of Deaf People as Disabled. Gallaudet, 2002

Obituary. British Deaf Monthly, 1897, 6, 151.

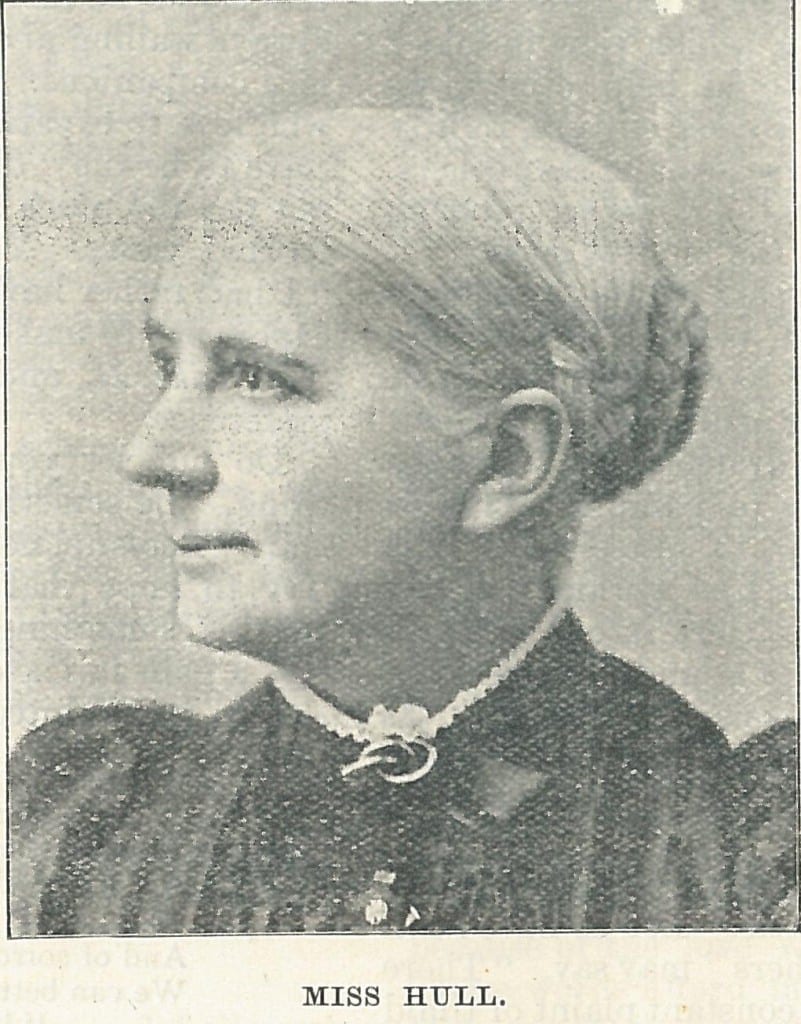

Portrait. British Deaf-Mute and Deaf Chronicle, 1894, 3, 36.

Buxton, D., On the Education of the Deaf and Dumb in Lancashire and Cheshire, Volume: 6 (1853-1854) Pages: 91-102

Buxton, D., On some results of the census of the deaf and dumb in 1861, Volume: 17 (1864-1865) Pages: 231-248

1891 census – Class: RG12; Piece: 3183; Folio: 67; Page: 19; GSU roll: 6098293

1861 census – Class: RG 9; Piece: 2683; Folio: 84; Page: 1; GSU roll: 543012

Alexander Watson (1815/16–1865): doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/28827

*[For the continuation of this exchange, I feel a future blog entry will be necessary]

Close

Close