Prize Letters from Abraham Fink, Catherine Lewis, and Edith Dingley, to ‘Our Monthly Church Messenger to the Deaf’, & a Deaf Private School

By H Dominic W Stiles, on 1 November 2019

Our Monthly Church Messenger to the Deaf was a London-based magazine, that was intended as a national church magazine for the Deaf. One of the main editors was the Reverend Fred Gilby. They had a regular children’s page written by ‘Aunt Dorothy’ and the editors offered prizes – we cannot say what – to letter writers. It seems there were some regular writers. In the June edition, there is a letter from Abraham Fink – not the first from him that year.

Abraham was, he tells us, 15 years and 5 months old, so would have been born in 1880/81. His birthplace was Russian Poland, and he was the son of Solomon and Rebecca Fink. I assume that the came to London in the 1880s.

The Finks had nine children altogether, and were Naturalized on the 7th of April, 1903, at which time Abraham is said to be twenty, and so ‘under age.’ He was in fact about 23, but presumably this saved him having to undergo the same process as a Deaf person, which might have been more difficult. Note that I spell naturalized with a ‘z’ – this is because the act was the ‘Naturalization Act.’ The family lived for many years at 49 Buxton Road – presumably now lost or with a changed name, but near Brick Lane.

Abraham attended the Summerfield, or Somerford Road School, and was a pupil of Mary Smart. After leaving school Abraham became a Cabinet Maker, his job in 1901, but later he became a Furrier, which was his job in 1911, at which time he was living at 8 Leman St, Aldgate. He married Deborah Cohen, a hearing girl, in 1908, and they had I think two sons, Bennett, and Gerald. He died in Harrow Hospital on the 7th of October, 1956. Another Deaf life that was unspectacular, but which illustrates the British Deaf experience in the last century.

Edith Maud Dingley was born in Birmingham, on the 17th of December. 1885, and was deaf from birth according to the 1911 census. Her father, Richard, was a Birmingham jeweller, and in 1911 they lived at 330 Hagley Road, Edgbaston. She never married, and she is given no occupation on the census return. She had lost a brother at Arras in 1917. The 1939 register says she was ‘incapacitated’ so perhaps she had other health issues, or was that just a code for her deafness? She died in 1943.

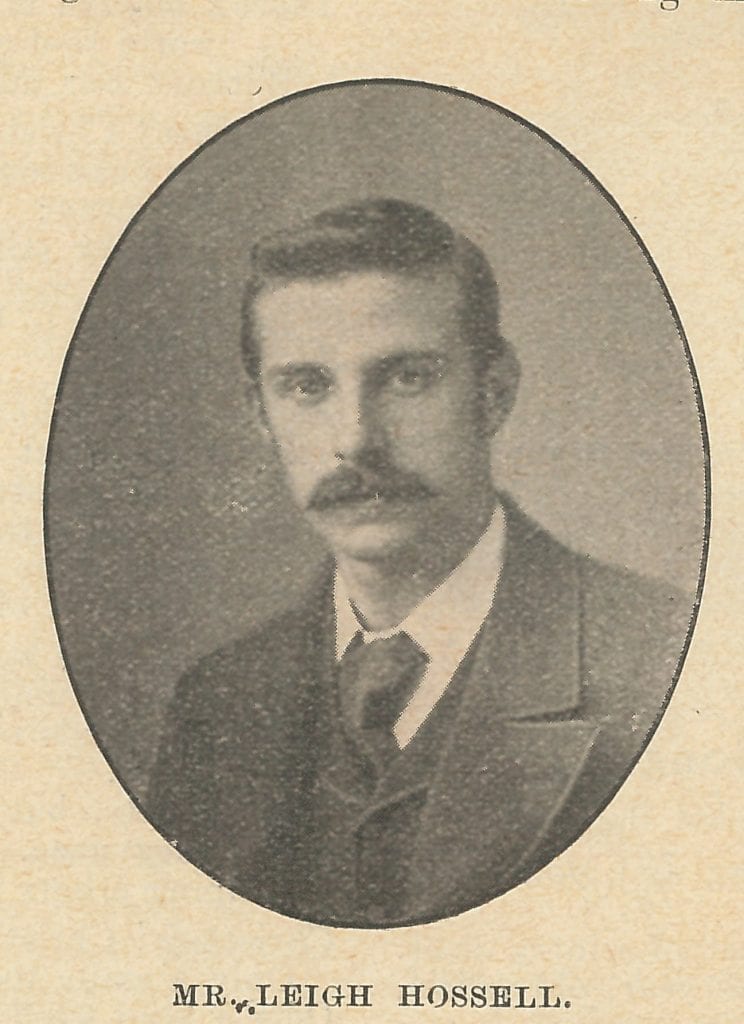

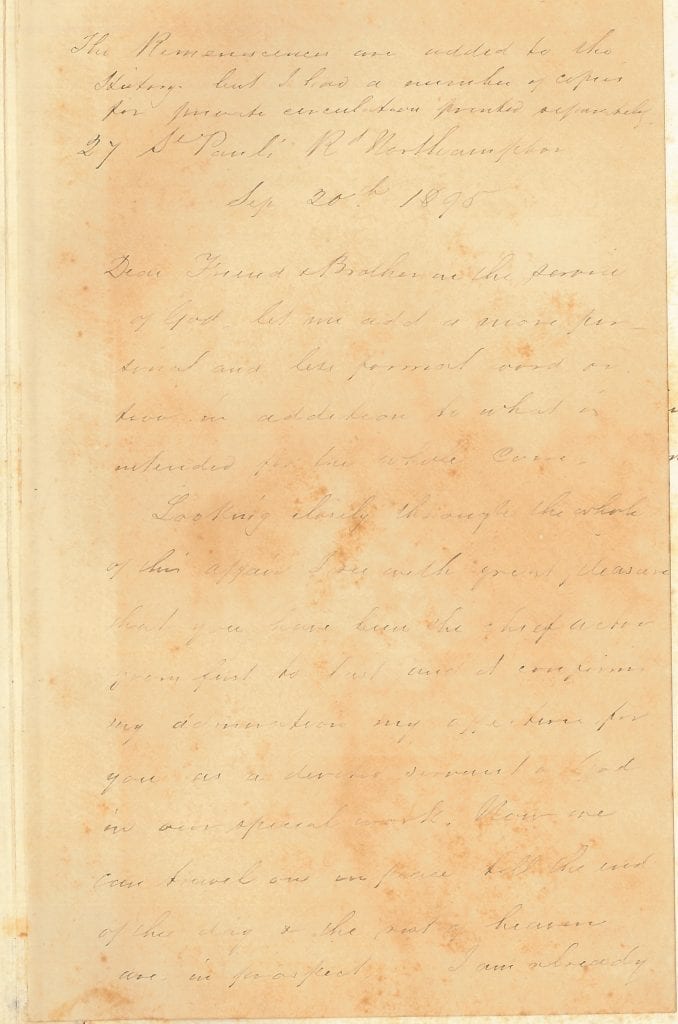

Catherine Lewis, was born in Bangor, North Wales, in 1884.* In the 1891 census, she was living in Sutton Coldfield, at a school in someone’s house, with five other deaf children. She was only seven at the time, and the household, headed by George Masters, a commercial Traveller, was at 70 Anchorage Road, Sutton Coldfield. I was fascinated to see that this was yet another private Deaf school, run by Fanny Masters, nee Fanny Armitage Rutherford (1860-1945) the wife of George. Her nephew, Albert Rutherford, son of her brother, was also Deaf, and living with the family.

1891 Census –

| George | Masters | Head | Male | 42 | 1849 | Cirencester | Gloucestershire | |

| Fanny A | Masters | Wife | Female | 31 | 1860 | Nottingham | Nottinghamshire | |

| Jenny A | Jones | Servant | Female | 26 | 1865 | Birmingham | Warwickshire | |

| Albert M | Rutherford | Nephew | Male | 19 | 1872 | Birmingham | Warwickshire | Deaf |

| Harriet F | Wacker | Pupil | Female | 15 | 1876 | Wolverhampton | Staffordshire | Deaf |

| John H | Croxford | Pupil | Male | 14 | 1877 | Gloucester | Gloucestershire | Deaf |

| Henry | Lowe | Pupil | Male | 9 | 1882 | Birmingham | Warwickshire | Deaf |

| Arthur R | Tatlow | Pupil | Male | 9 | 1882 | Glasgow | Deaf | |

| Catherine | Lewis | Pupil | Female | 7 | 1884 | Bangor | Caernarvonshire | Deaf |

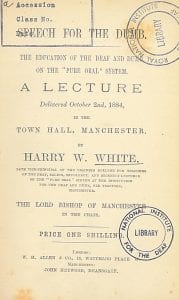

In the 1881 census, Fanny Rutherford and her nephew Albert, were at the oralist Ealing Training College, the Society for Training Teachers of the Deaf and for the Diffusion of the German System.

In the 1901 census – (at Gravelly Hill, Erdington)

| George Masters | Head | 52 | 1849 | Male | Cirencester, Gloucestershire, England |

| Fanny Armitage Masters | Wife | 41 | 1860 | Female | Nottingham, Nottinghamshire, England |

| Albert M Rutherford | Nephew | 29 | 1872 | Male | Birmingham, Warwickshire, England |

| Ethel Perkins | Boarder | 11 | 1890 | Female | Astwood Bank, Warwickshire, England |

| Minnie Pountney | Servant | 19 | 1882 | Female | Birmingham, Warwickshire, England |

In the 1911 census –

| George Masters | Head | 1849 | 62 | Male | Married | Companys Secretary | Cirencester | 72Kingsbury Road Gravelly Hill Birmingham |

| Fanny Armitage Masters | Wife | 1860 | 51 | Female | Married | School For Deaf Children | Nottinghamshire | 72Kingsbury Road Gravelly Hill Birmingham |

| Mildred Rutherford | Sister | 1839 | 72 | Female | Widowed | Living On own Means | Cirencester | 72Kingsbury Road Gravelly Hill Birmingham |

| Albert Masters Rutherford | Nephew | 1872 | 39 | Male | Single | Merchants Clerk | Birmingham | 72Kingsbury Road Gravelly Hill Birmingham |

| Cecil Hull Jordan | Pupil | 1895 | 16 | Male | Single | At School | Handsworth, Birmingham | 72Kingsbury Road Gravelly Hill Birmingham |

| Dorothy Violet Lepage Sanders | Pupil | 1895 | 16 | Female | Single | At School | Crudwell Nr Malmesbury | 72Kingsbury Road Gravelly Hill Birmingham |

| James Gordon Calder | Pupil | 1901 | 10 | Male | Single | At School | Smethwick | 72Kingsbury Road Gravelly Hill Birmingham |

| Winifred Adams | Servant | 1892 | 19 | Female | Single | Domestic Servant General | Walsall | 72Kingsbury Road Gravelly Hill Birmingham |

It would make a really interesting project, to trace all those Ealing teachers and see where they ended up, then look at census returns and map and follow through with all their pupils.

Anyway, we can also now see that Edith Dingley was one of Fanny Masters’s pupils as well. It seems that middle class families were the people who most feared sending their children to ‘ordinary’ public Deaf Schools, and chose instead small private schools.

I do not know what happened to Catherine after leaving school.

*Thanks to John Lyons for identifying Catherine Lewis in the 1891 census, and enabling me to write a bit about her story.

Abraham Fink

Naturalization – Class: HO 334; Piece: 35

1891 Census – Class: RG12; Piece: 265; Folio: 30; Page: 55

1901 Census – Class: RG13; Piece: 304; Folio: 18; Page: 28

1911 Census – Class: RG14; Piece: 1489

Edith Dingley

1891 Census – Class: RG12; Piece: 2390; Folio: 47; Page: 3

1901 Census – Class: RG14; Piece: 17917; Schedule Number: 237

1911 Census – Class: RG13; Piece: 2814; Folio: 150; Page: 13

1939 Register – Reference: RG 101/5526A

Catherine Lewis

1891 Census – Class: RG12; Piece: 2438; Folio: 90; Page: 13

Fanny Masters

1881 Census – Class: RG11; Piece: 1344; Folio: 48; Page: 51; GSU roll: 1341327

1901 Census – Class: RG13; Piece: 2875; Folio: 130; Page: 41

1911 Census – Class: RG14; Piece: 18341

1939 Register; Reference: RG 101/5490G

Close

Close