“there is nothing, as I have said, in this mortal life except inanity, emptiness, and dream-shadows” – Girolamo Cardano 1501-76

By H Dominic W Stiles, on 1 June 2018

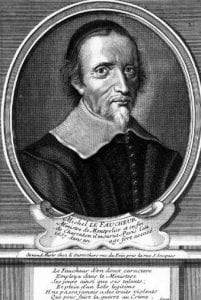

Girolamo Cardano (1501-76), or Hieronymus Cardanus, or Jerome Cardan, to use the Italian, Latin and English forms of his name, was born in Pavia. His family lived in Milan during its occuption by the French. His father was a lawyer. Jerome was a sickly child, and seems to have had more than his fair share of accidents. He attended the academy at Pavia, now the university, where he first lectured on Euclid (Cardano, p.11-13). When he was twenty-five he became a doctor of medicine in Padua.

Attempting to make money from gambling, Cardano was the first person to work out the science of probability, though he did not get the credit for being first as he wanted the advantage of keeping the information to himself, and did not publish it in his lifetime.

Rejected by the Milanese College of Physicians (until 1539), he felt snubbed and was forced to make his reputation in the provinces (see Hannam, p.238). His philosophy was to allow patients to heal naturally so he did not introduce invasive and painful treatments to patients, rather prescibing rest & sensible eating. This meant he was more successful than his fellows. He was invited to Scotland by John Hamilton the archbishop of St. Andrews in 1551, who was very ill, and the archbishop recovered, and was full of praise for Cardano (ibid p.239).

He was rather obsessed by horoscopes, predicting he would die aged 45. He prepared horoscopes of historical figures, including Jesus, though that later got him into trouble with the Inquisition.

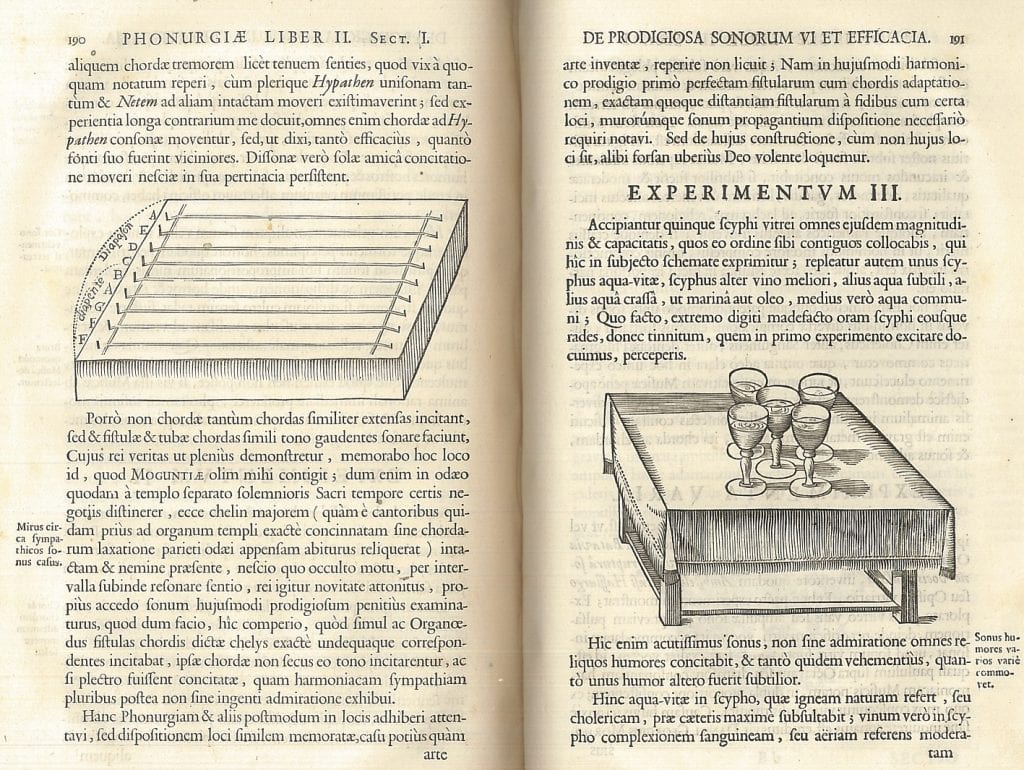

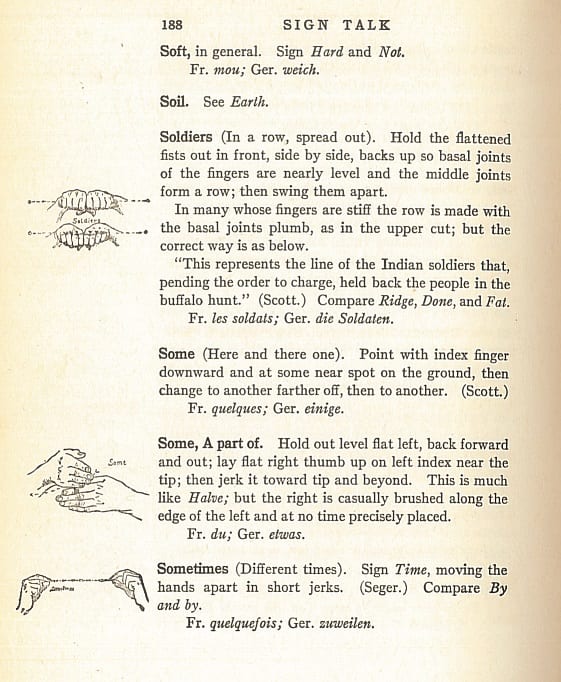

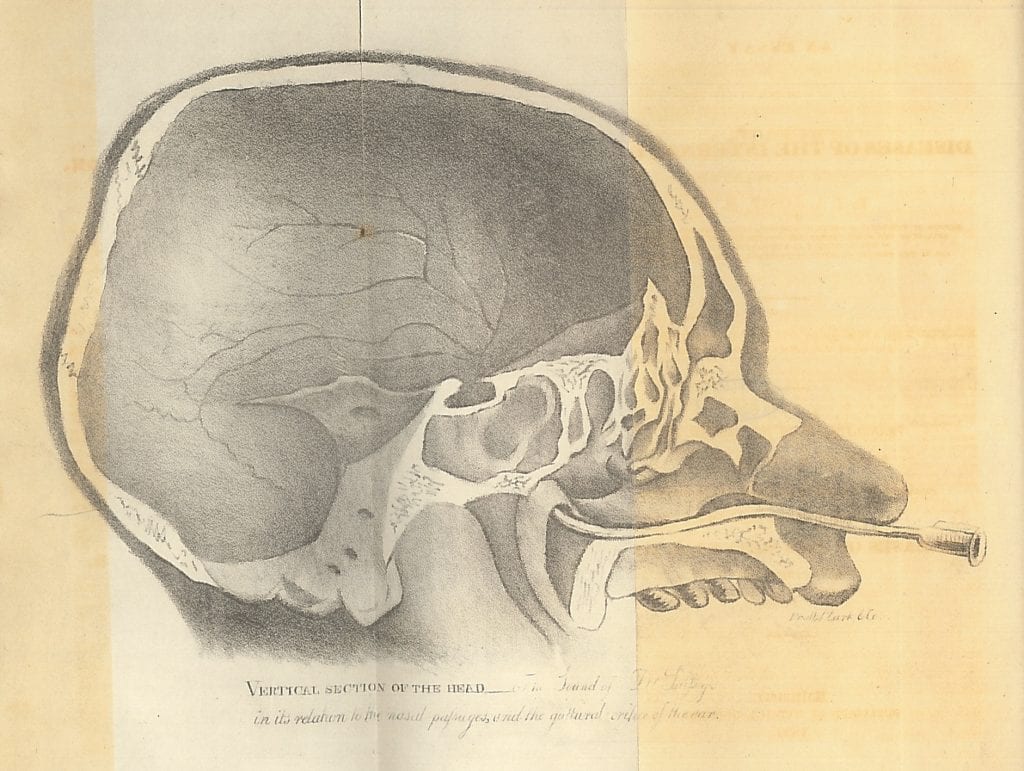

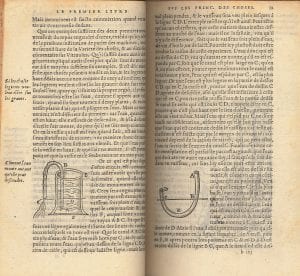

We have a French version of De subtilitate rerum – On natural phenomena, whence came the illustrations here.

He was a remarkable and fascinating man, and his memoir makes for a lively and vivid read. He is resonably honest and certainly phlegmatic. The behaviour of his sons might have crushed a lesser man, one being a violent criminal, and the other in an unhappy marriage poisoned his wife and was executed.

“I am by no means unaware that these afflictions may seem meaningless to future generations, and more especially to strangers; but there is nothing, as I have said, in this mortal life except inanity, emptiness, and dream-shadows.” (p.83-4)

Below we see the page on the beaver. For some reason, perhaps connected with the use of Castoreum, according to Aesop’s Fables and then Pliny the Elder, mediaeval tradition said beaver’s would chew off their own testicles to escape hunters. As a beaver’s testicles are internal, perhaps that contributed to the myth. Cardano, Girolama, The Book Of My Life. Translated by Jean Stoner (2002)

Cardano, Girolama, The Book Of My Life. Translated by Jean Stoner (2002)

Les livres de Hierosme Cardanus medecin milannois: intitulez de la subtilité, & subtiles inuentions, ensemble les causes occultes, & raisons d’icelles. Traduits… Richard Le Blanc, Paris, Pour Pierre Cauelat ruë S. Iaques, à l’enseigne de l’escu de Florence (1584)

Hannam, James, God’s Philosophers (2009)

Close

Close