Alphabet, Manuel-Figure des Sourds-Muets de Naissance, An VIII (1799-1800)

By H Dominic W Stiles, on 17 March 2017

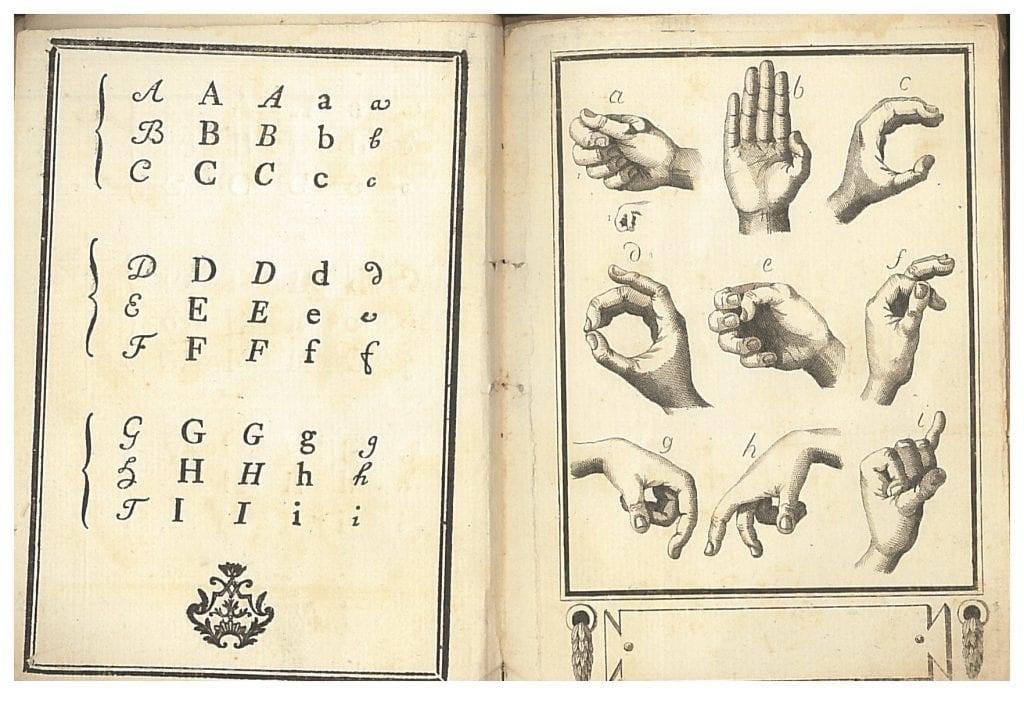

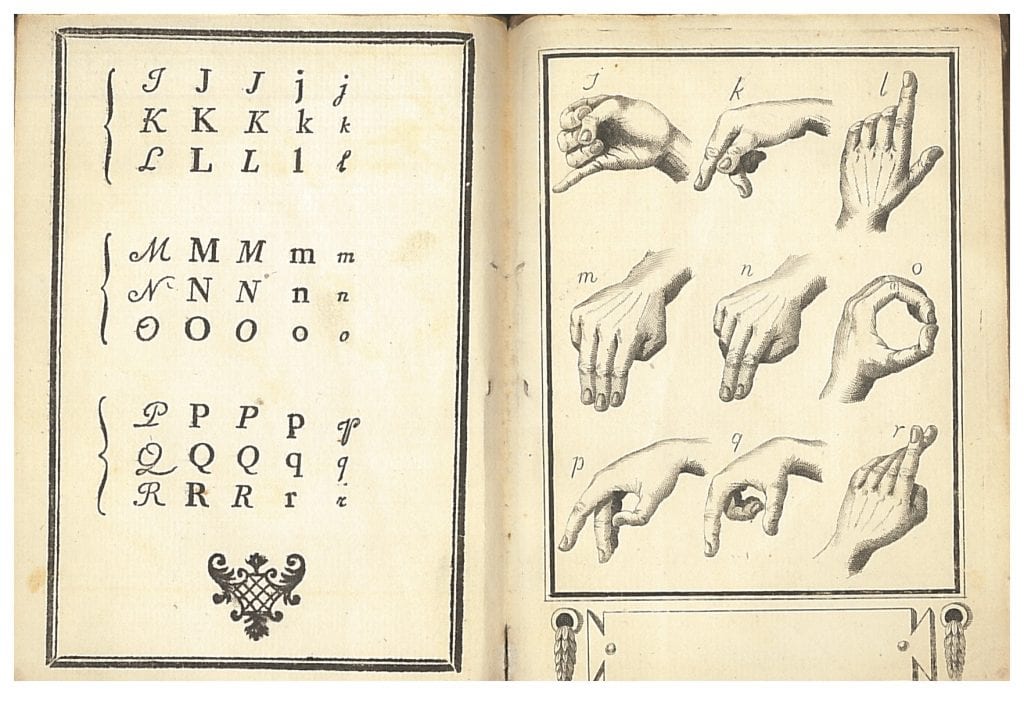

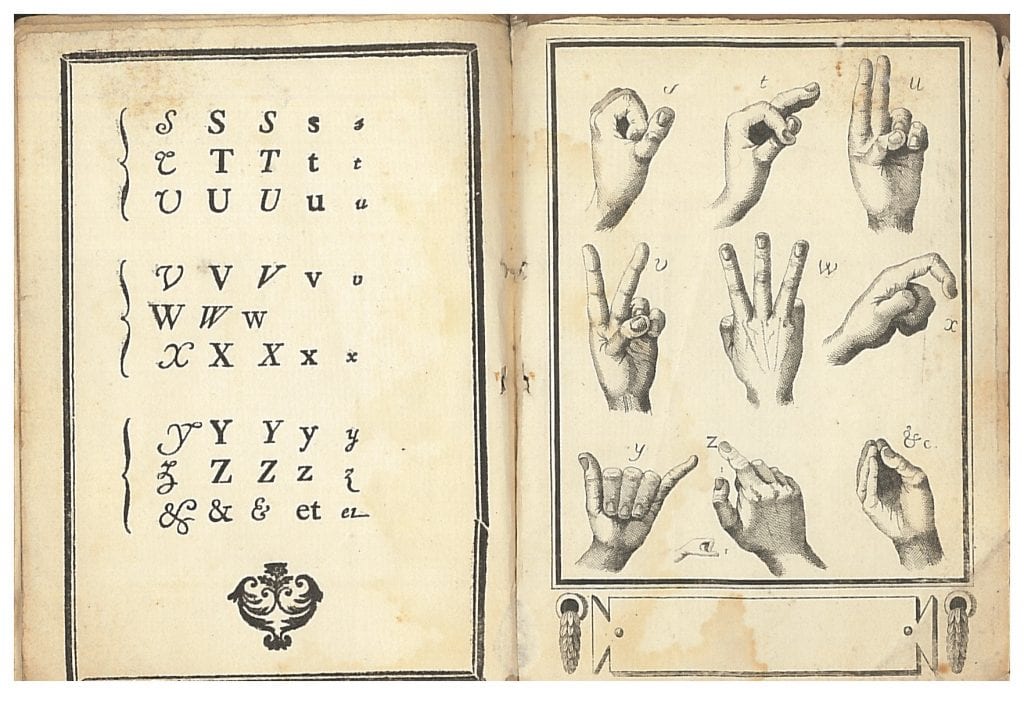

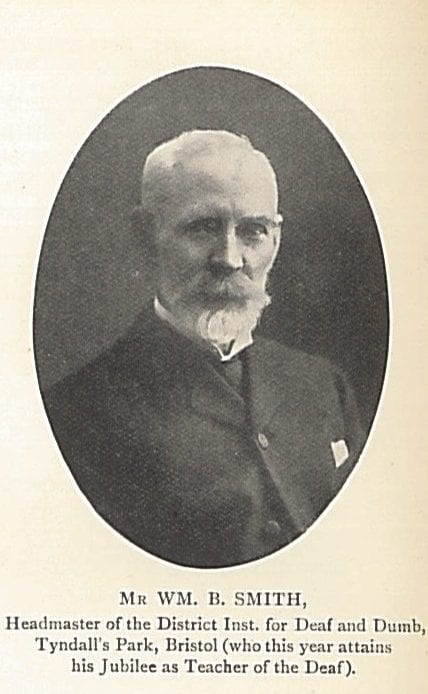

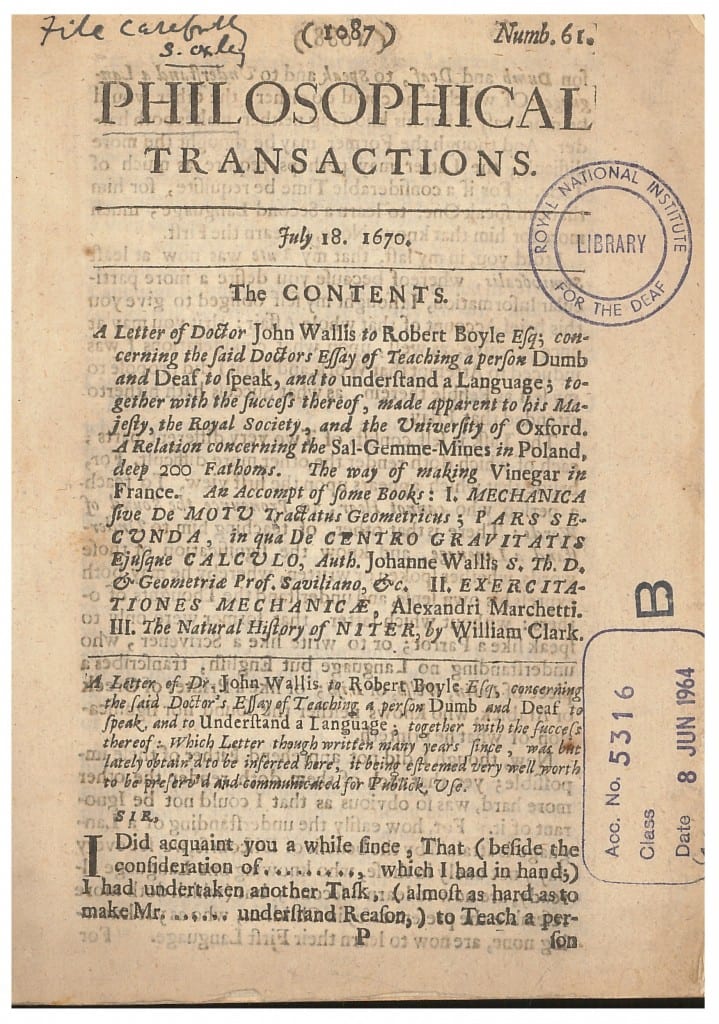

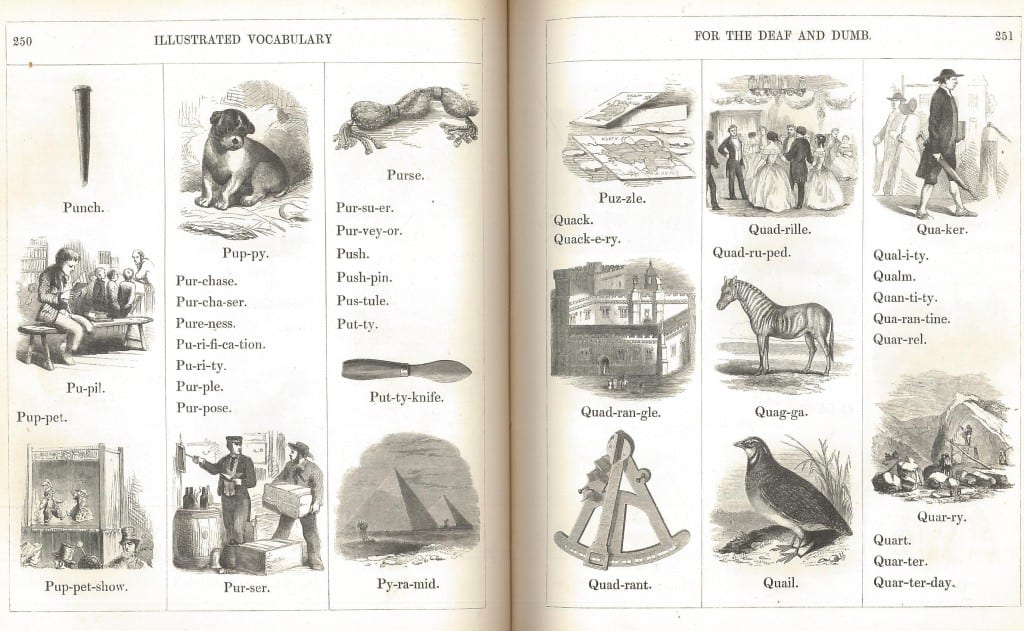

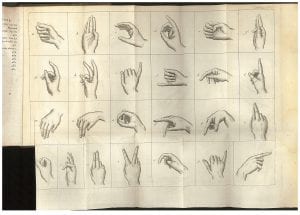

A year or so ago we came across, in our French language collection, this extremely rare manual alphabet – Alphabet, Manuel-Figure des Sourds-Muets de Naissance. It was printed in Paris, in an VIII, revolutionary year 8, which dates from the 23rd of September, 1799, to the 22nd of September, 1800. That was the period when Bonaparte returned from Egypt and used his popularity to instigate the coup of 18 Brumaire, becoming ‘consul’ and virtual dictator. It was possibly printed by the pupils (boys) of the Institution Nationale des Sourds-Muets à Paris, then under the principal, the Abbé Sicard. Sicard had an extraordinary life, narrowly avoiding execution during the French Revolution in 1792, when he was arrested by the Revolutionary Commune for failing to take the oath of civil allegiance. You can read about that in Harlan Lane’s book, When the Mind Hears (1984, see chapter 2 in particular), and in the more recent Abbé Sicard’s deaf education : empowering the mute, 1785-1820 (2015) by Emmet Kennedy. The coup of 18 Fructidor sent Sicard into hiding, and he only emerged when Bonaparte came to power. We have a copy of Sicard’s first book published in an VIII (year 8), Cours d’instruction d’un sourd-muet de naissance, pour servir a l’éducation des sourds-muets, but it appears that the sign alphabet that is supposed to be in it, is missing from the first edition we have. Here it is from the back of the 1803 second edition. Click for a larger size.

A year or so ago we came across, in our French language collection, this extremely rare manual alphabet – Alphabet, Manuel-Figure des Sourds-Muets de Naissance. It was printed in Paris, in an VIII, revolutionary year 8, which dates from the 23rd of September, 1799, to the 22nd of September, 1800. That was the period when Bonaparte returned from Egypt and used his popularity to instigate the coup of 18 Brumaire, becoming ‘consul’ and virtual dictator. It was possibly printed by the pupils (boys) of the Institution Nationale des Sourds-Muets à Paris, then under the principal, the Abbé Sicard. Sicard had an extraordinary life, narrowly avoiding execution during the French Revolution in 1792, when he was arrested by the Revolutionary Commune for failing to take the oath of civil allegiance. You can read about that in Harlan Lane’s book, When the Mind Hears (1984, see chapter 2 in particular), and in the more recent Abbé Sicard’s deaf education : empowering the mute, 1785-1820 (2015) by Emmet Kennedy. The coup of 18 Fructidor sent Sicard into hiding, and he only emerged when Bonaparte came to power. We have a copy of Sicard’s first book published in an VIII (year 8), Cours d’instruction d’un sourd-muet de naissance, pour servir a l’éducation des sourds-muets, but it appears that the sign alphabet that is supposed to be in it, is missing from the first edition we have. Here it is from the back of the 1803 second edition. Click for a larger size.

Was Alphabet, Manuel-Figure printed for the use of the pupils, or to sell in order to raise money? Was it printed by the pupils, as an exercise, or a way of learning a trade? I think we may well attribute Sicard as the man behind the publication, but perhaps it was just publicity material for the school with another teacher responsible. It is beyond my expertise to say anything more about the Alphabet, so I present the printed pages. It is not printed on every page, and I suspect it was printed on one sheet, then folded and cut, but if you have a more informed view about how it may have been laid out, please contribute below.

I think that this item is, as I said above, extremely rare, but it may well be unique. The small plaque under each picture is probably aesthetic, but seems to me to make the pictures seem more ‘monumental’ and, if I dare use the term, (it may be legitimate here!), ‘iconic.’ Now compare the hand shapes in the 1803 alphabet above, with those in our 1799 one below. See the interesting differences. Is one drawn by a ‘reader’ of the signs, and one by the ‘speaker’, or is one drawn by the artist from his (or her) own hand shapes? Is the 1799 Cours d’instruction alphabet different? If both were by Sicard, would they not be identical, or could that just be a matter of the artist executing the engravings?

It measures approximately 14cm by 23cm. We are in the process of getting many of these books, previously on card index only, onto the UCL catalogue, to make them more ‘visible’ to researchers.

The pages between those below, are blank.

Cours d’instruction d’un sourd-muet de naissance, pour servir a l’éducation des sourds-muets – on Google Books, unfortunately lacks the sign alphabet at the back.

Close

Close