Arthur Wellesley, the Duke of Wellington, who was born 250 years ago, in 1769, suffered from noise-related hearing loss caused by artillery. William Wright tells us,

The Duke of Wellington was inspecting an experimental carriage for a howitzers and whilst in advance of the gun, gave the word ” Fire ;” the result was the rupture of the membrane of the drum of the left ear. The Duke went immediately to Mr. Stevenson who told his Grace the story, about thickening the drum of the ear. The solution of caustic was applied; instant pain ensued, from the caustic passing through the ruptured membrane amongst the ossicula, and very sensitive internal tissues. Within six hours the Duke was conveyed home from Lord Liverpool’s, in a state of insensibility, and it was only by most careful, skilful treatment that his life was then preserved. He went to Verona, a great sufferer, and the country had very properly to make a handsome compensation to Dr. Hume, and his family, for giving up his practice to attend the Duke on his mission. (Wright, 1860, p.75-6)

Graham Smelt says that this was on On August the 5th, 1822. His hearing loss was made considerably worse by the botched treatment, a story related by a Mr Gleig, in an anecdote that suggests it was Hume who was to blame –

The Duke, many years ago, being deaf, sent for his medical man, who poured some stuff into his ear, not knowing that the drum of the ear was broken. This proved very mischievous in its results. The Duke said it was not sound that was restored to him; it was something terrifically beyond sound: the noise of a carriage passing under his window was like the rolling of thunder. Thus suffering, he returned home about the middle of the day, and went to bed. Next day, Dr. Hume called and found the Duke staggering about the room. Dr. Hume, although he well knew the Duke’s temperate habits, supposed that he had taken a little too much wine overnight, and had not recovered from it. He was leaving the room, when the Duke said to him : Hume, I wish you would look to my ear ; there is something wrong there.’ Hume looked and saw that a furious inflammation had begun, extending to the brain ; another hour, and the stuff would have done for the Duke what all his enemies had failed to do : it would have killed him. Hume bled him copiously, sent for Sir Henry Halford and Sir Astley Cooper, who treated him with great skill, and brought him round. The poor man came next day and expressed his great regret. The Duke spoke to him in his kindest manner and said, I know you did not mean to harm me ; you did your best, but I am very deaf.’ Upon which, the Doctor said, I am very sorry for it ; but my whole professional prospects are at stake, and if the world hears of it I shall be ruined.’ ‘The world need not hear at all about it,’ said the Duke; ‘keep your counsel, and I’ll keep mine.’ The Doctor, encouraged by this, went a little further : Will you let me attend you still, and let the world suppose that you still have confidence in me ?’ ‘No, no,’ said the Duke, ‘I cannot do that ; that would not be truthful.’ (Davies, 1854 p.16-17)

The Duke, many years ago, being deaf, sent for his medical man, who poured some stuff into his ear, not knowing that the drum of the ear was broken. This proved very mischievous in its results. The Duke said it was not sound that was restored to him; it was something terrifically beyond sound: the noise of a carriage passing under his window was like the rolling of thunder. Thus suffering, he returned home about the middle of the day, and went to bed. Next day, Dr. Hume called and found the Duke staggering about the room. Dr. Hume, although he well knew the Duke’s temperate habits, supposed that he had taken a little too much wine overnight, and had not recovered from it. He was leaving the room, when the Duke said to him : Hume, I wish you would look to my ear ; there is something wrong there.’ Hume looked and saw that a furious inflammation had begun, extending to the brain ; another hour, and the stuff would have done for the Duke what all his enemies had failed to do : it would have killed him. Hume bled him copiously, sent for Sir Henry Halford and Sir Astley Cooper, who treated him with great skill, and brought him round. The poor man came next day and expressed his great regret. The Duke spoke to him in his kindest manner and said, I know you did not mean to harm me ; you did your best, but I am very deaf.’ Upon which, the Doctor said, I am very sorry for it ; but my whole professional prospects are at stake, and if the world hears of it I shall be ruined.’ ‘The world need not hear at all about it,’ said the Duke; ‘keep your counsel, and I’ll keep mine.’ The Doctor, encouraged by this, went a little further : Will you let me attend you still, and let the world suppose that you still have confidence in me ?’ ‘No, no,’ said the Duke, ‘I cannot do that ; that would not be truthful.’ (Davies, 1854 p.16-17)

To me this sounds like a well-rehearsed anecdote, but there is something ‘missing,’ it seems to me, in Wright’s account, in that he seems to imply that Hume had some hand in the affair without explicitly saying so. Or is he just omitting Stevenson’s name, and ‘the poor man’ is Stevenson? Smelt says that Stevenson was to blame, and that Hume treated him afterwards. In an earlier book, Wright tells us –

To me this sounds like a well-rehearsed anecdote, but there is something ‘missing,’ it seems to me, in Wright’s account, in that he seems to imply that Hume had some hand in the affair without explicitly saying so. Or is he just omitting Stevenson’s name, and ‘the poor man’ is Stevenson? Smelt says that Stevenson was to blame, and that Hume treated him afterwards. In an earlier book, Wright tells us –

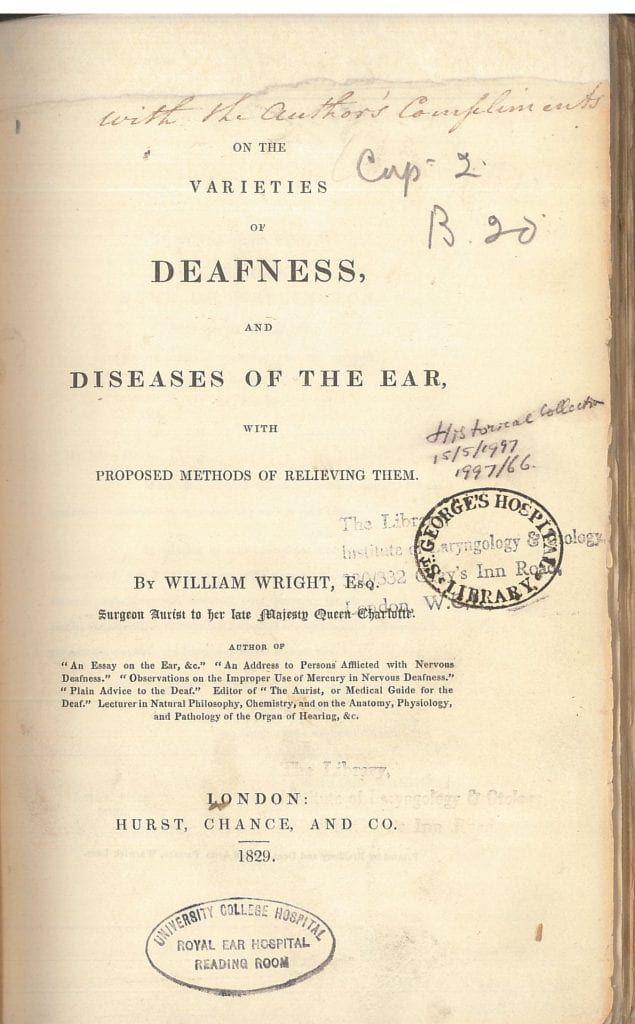

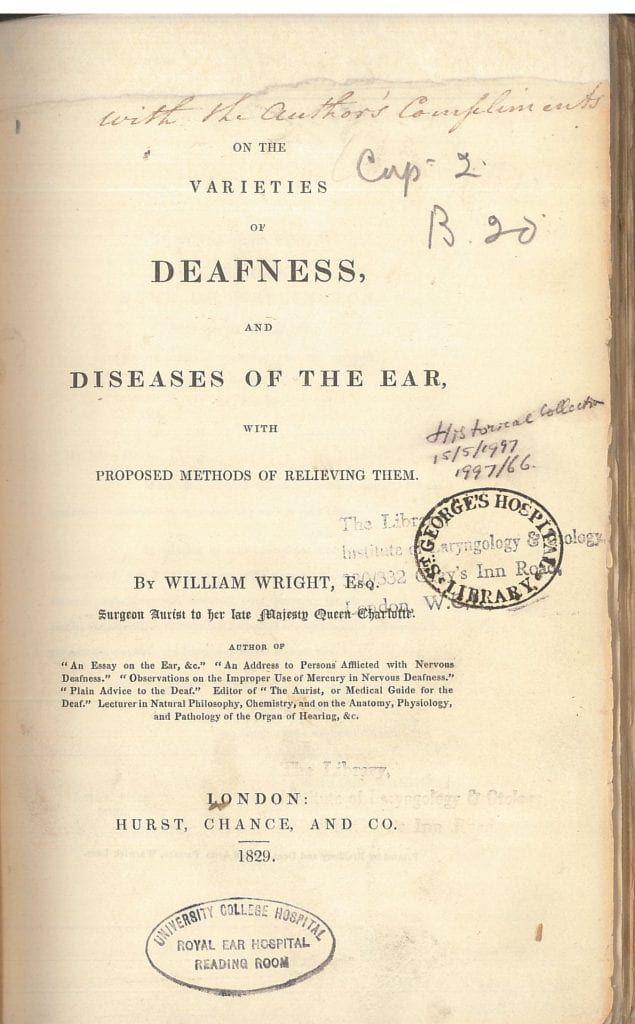

Deleau states that he can reach the cavity of the tympanum by a bent probe, or catheter. If he even can do so, which I consider is very problematical, I am convinced the operation is attended with considerable danger, for the ossicula (the small bones) which extend from the inside of the membrana tympani, to the opposite side of the cavity, would be in great danger of being forced from the situation in which Providence has been pleased to place them, or their functions would be otherwise diminished, or destroyed, and such would be the effect of any injury being inflicted on this delicate organization, that inflammation of the brain, and even death, would be a probable consequence. An example of this was unfortunately nearly afforded about the end of 1822, or beginning of 1823, in the case of the Duke of Wellington, a lotion of lunar caustic had been dropped into the external auditory passage, there was an opening at the time through the membrane (or drum), from an accidental cause, and the caustic lotion entered the cavity beneath, containing the highly sensative [sic] integuments, and machinery therein placed ; the results were intense pain; in a few hours inflammation of the brain, with symptomatic fever, and his life was only preserved by the most prompt and efficient treatment pursued by his Physician, aided by other medical and surgical advice derived from the first men of the age. In June, 1823, I was called into attendance on his Grace, as his aurist, and continue still to attend him when necessary ; even at this distant period from the unfortunate occurrence, the Duke feels sufficient unpleasant effects occasionally, not to allow him to forget it, independent of the privation of his left ear.* Similar, if not even worse, must necessarily be the consequence of introducing an instrument into the cavity of the tympanum, even if the patient be in a state of health; but if there exist any tendency to inflammatory action, scrofula, or erysipelas, the danger is increased, and the disastrous effects, or even fatal termination of the experiment, for it is nothing more in ninety-nine cases out of a hundred, unavoidable. (Wright, 1839, p.55-7)

* In pp. 159 and 160, of “An Exposition of Quackery and Imposture in Medicine,” written by Dr. Caleb Ticknor, of New York, republished in this country, which I edited, and upon which I wrote copious notes, will be found a further account of the Duke of Wellington’s case.

Note how free doctors were then with patient information, while the patient was still alive. Smelt suggests as well as the seriously damaged ear, he also had noise-induced hearing loss in his other ear as he got older.

In 1852 the Duke wrote in a letter,

I have none of the infirmities of old age I excepting Vanity perhaps. But that is a disease of the mind, not of the Body ! My deafness is accidental ! If I was not deaf, I really believe that there is not a youth in London who could enjoy the world more than myself or could bear fatigue better, but being deaf, the spirit, not the body, tires. One gets bored, in boring others, and one becomes too happy to get home. (Wellington, 1854, p.314-5)

Losing his hearing had other consequences, as we see from this on February 20th, 1848 from the Greville memoirs –

At the House of Lords on Friday night, for the Committee on the Diplomatic Bill. Government beaten by three, and all by bad management ; several who ought to have been there, and might easily have been brought up, were absent : the Duke of Bedford, Duke of Devonshire, Lord Petre, a Catholic, dawdling at Brighton, and Beauvale. The Duke of Wellington, with his deafness, got into a complete confusion, and at the last moment voted against Government. (Greville, 1888, p.129)

When he was in his eighties, as members of Derby’s 1852 government were announced, the now quite deaf Duke kept repeating, “Who? Who?” It became known as the “Who? Who?” ministry.

Davies, George Jennings, The completeness of the late duke of Wellington as a national character, 1854

Greville, Charles Cavendish Fulke, The Greville Memoirs: A Journal of the Reigns of King George IV, King … 1888

Hazlitt, William, ed, Arthur Wellesley Duke of Wellington, The Speeches of the Duke of Wellington in Parliament, Volume 2, 1854

Smelt, Graham, Wellington’s Deafness. Abstract presented at the meeting British Society for the History of ENT, Held December 1st 2011 In the Toynbee McKenzie Room, at the Royal Society of Medicine, London

Wright, William, A few minutes’ advice to deaf persons…, 1839

Wright, William, On the varieties of deafness and diseases of the ear, 1829

Wright, William, Deafness and Diseases of the Ear: The Fallacies of Present Treatment Exposed … 18

Filed under Audiology, Deaf History, Deaf people, ENT History, Health, Hearing loss, Old books, Science, Tinnitus, Vertigo & dizziness

Tags: tinnitus, vertigo

Comments Off on “but being deaf, the Spirit not the Body tires” – the Duke of Wellington’s Hearing Loss

Close

Close