“Brandy for giddiness, 2s” – Jonathan Swift’s Meniere’s Disease

By H Dominic W Stiles, on 13 April 2018

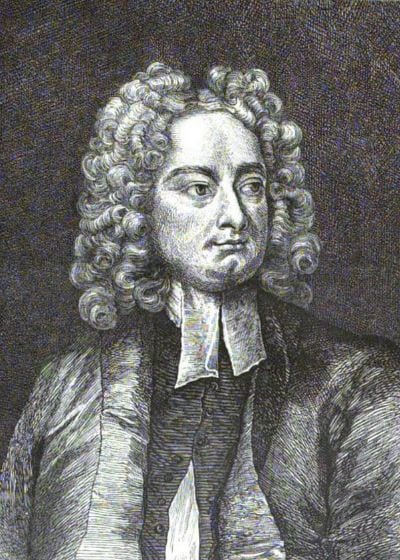

One of the great writers of English, Jonathan Swift (1667-1745) was plagued for much of his life by bouts of giddiness, and by increasing deafness, though in many other respects he was healthy and lived to the age of seventy-seven. It sometimes incapacitated him for long periods.

In August 1727 he wrote to Lady Henrietta Howard,

About two hours before you were born, I got my giddiness by eating a hundred golden pippins at a time at Richmond, and, when you were five years and a quarter old, baiting 2 days, I got my deafness, and these two friends, one or other, have visited me, every year since: and being old acquaintances, have now thought fit to come together.

It seems to have begun when he was twenty, according to the autobiographical notes in Forster’s biography (p.27), but there, there is a footnote inserted that says Swift had added, “in 1690.” The word ‘hours’ in the letter to Henrietta Howard may be an error for, or misreading of, ‘years,’ or it could be he had forgotten precisely when it happenened.

At first he self-medicated – on the 16th of November, 1708, he wrote “Brandy for giddiness, 2s.”

Bucknill (p.495-6) quotes Swift’s ‘Journal to Stella’ for October 1710: “This morning, sitting in my bed, I had a fit of giddiness; the room turned round for about a minute and then it went off leaving me sickish, but not very. I saw Dr. Cockburn to-day, and he promises to send me the pills that did me good last year; and likewise has promised me an oil for my ears, that he has been making for that ailment for somebody else.” The diagnosis seems to be that he had Ménière’s disease (see Bucknill and Bewley).

Some years after the letter, several newspapers published a poem that Swift had written about his illness, both in Latin and in English (Grub Street Journal, Thursday, November 14, 1734; Issue 255), although the version with the answers seems to be later –

Vertiginosus, inops, surdus, male gratus amicis;

Non campana sonans, tonitru non ab Jove missum,

Quod mage mirandum, saltem si credere fas est,

Non clamosa meas mulier jam percutit aures.DOCTOR: Deaf, giddy, helpless, left alone.

ANSWER: Except the first, the fault’s your own.

DOCTOR: To all my friends a burden grown.

ANSWER: Because to few you will be shewn.

Give them good wine, and meat to stuff,

You may have company enough.

DOCTOR: No more I hear my church’s bell,

Than if it rang out for my knell.

ANSWER: Then write and read, ’twill do as well.

DOCTOR: At thunder now no more I start,

Than at the rumbling of a cart.

ANSWER: Think then of thunder when you fart.

DOCTOR: Nay, what’s incredible, alack!

No more I hear a woman’s clack.

ANSWER: A woman’s clack, if I have skill,

Sounds somewhat like a throwster’s mill;

But louder than a bell, or thunder:

That does, I own, increase my wonder.

Although he lived to a good age, Swift’s final few years seem to have found him the victim of what Bewley calls, ‘terminal dementia’ (p.604).

Bewley, Thomas, The health of Jonathan Swift. J. R. Soc. Med. 1998;91 :602-605

Bewley, Thomas, The health of Jonathan Swift. J. R. Soc. Med. 1998;91 :602-605

Bucknill JC. Dean Swift’s disease. Brain 1881;4:493-506

Forster, John, The Life of Jonathan Swift, Volume 1

The Works of the English Poets. With Prefaces, Biographical and …, Volume 40

Close

Close