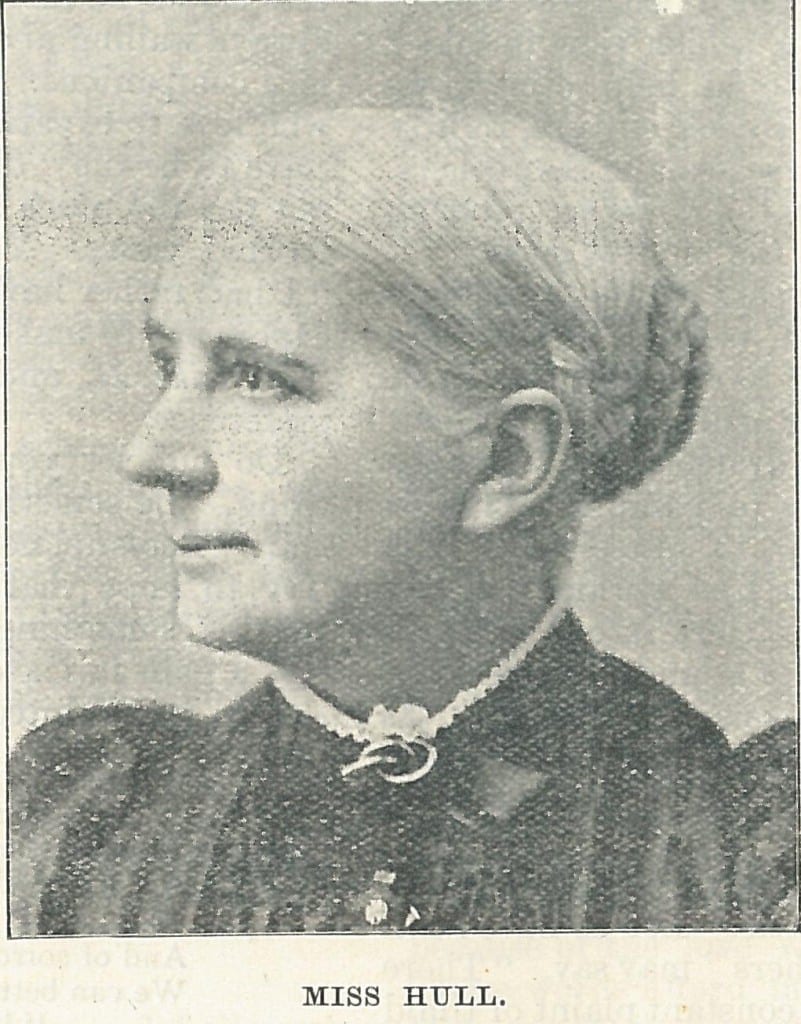

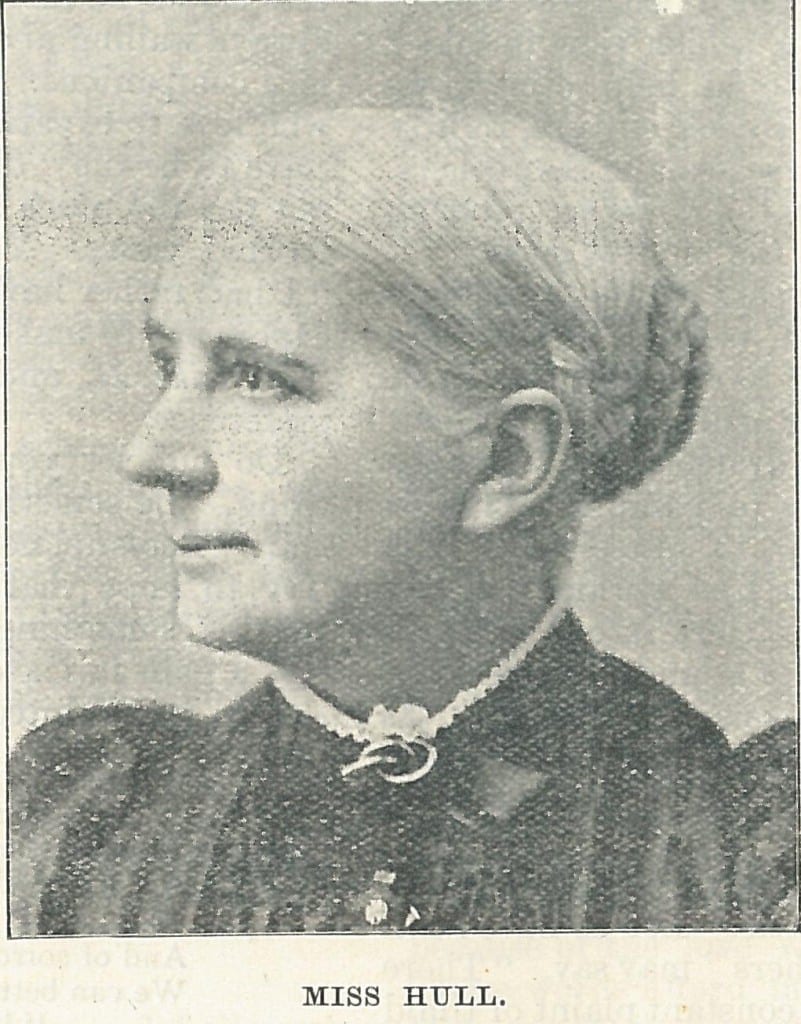

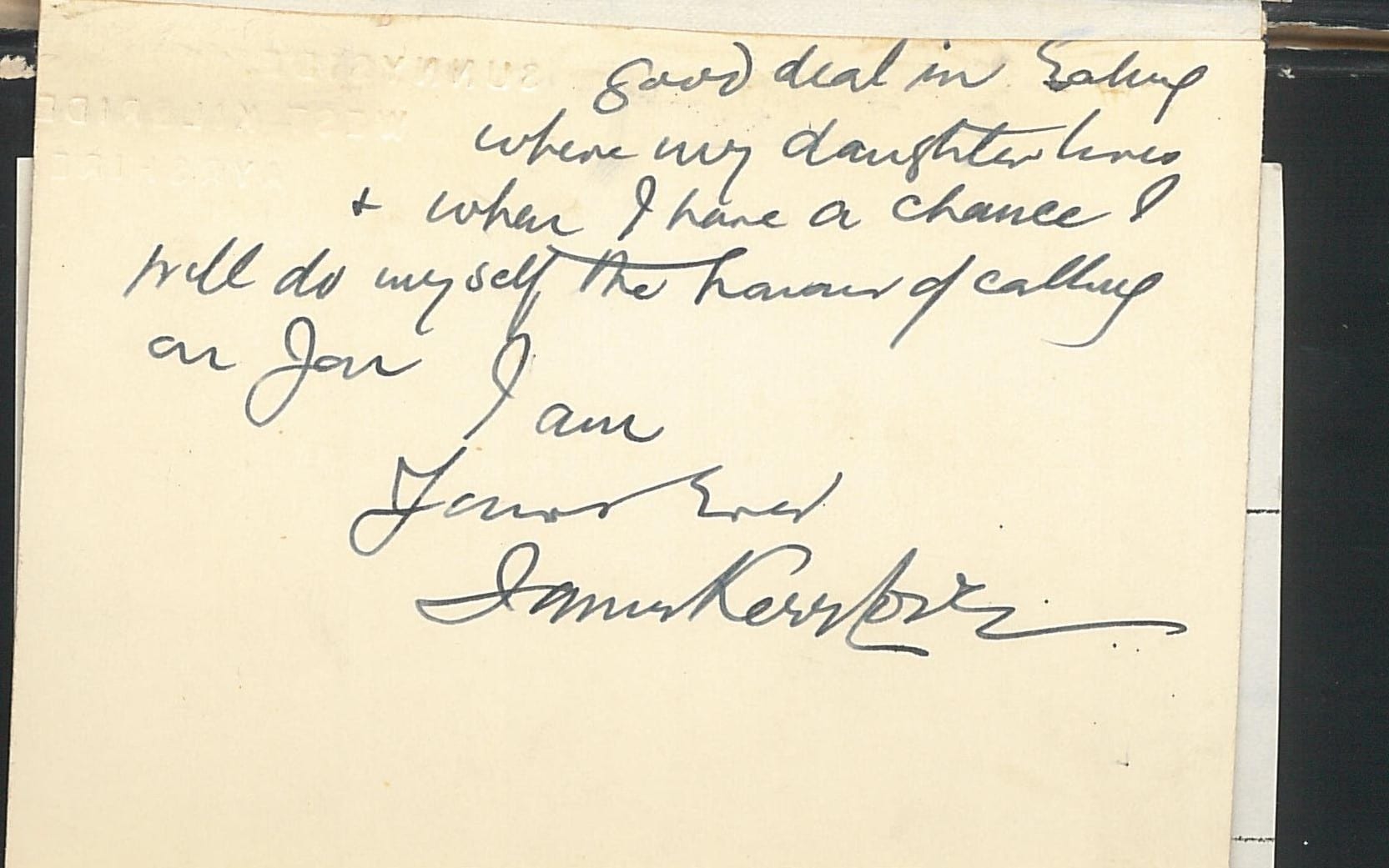

Susannah Elizabeth Hull, (1843-1922) was born with her twin Agnes in Camberwell, daughter to George Hull a Scottish Doctor and his wife Susanna. He was a member of the Royal College of Surgeons, Edinburgh, and the Royal College of Physicians, Edinburgh. In 1851 the family were living in Tonbridge, Kent, but her father clearly prospered in his medical practice as by 1861 they were living in Kensington. Susannah is hardly remembered today, but she was one of the British representatives at the Milan Conference, and knew Alexander Graham Bell well. She was first attracted to work with deaf children on reading about Laura Bridgeman, the American deaf-blind lady according to British Deaf Monthly, and was told by her father of the case of two deaf children. She wrote to the British Deaf Monthly to correct several inaccuracies in their story (Hodgson 1953, p.207-8, BDM vol 9 p.103). In 1862-3 she became interested in a small girl who was left deaf, blind, and paralysed by scarlet fever. She was, we are told, encouraged by Dickens’s account of the deaf-blind lady, Laura Bridgman, which he wrote in American Notes. Accordingly she opened a small home school in 1862, in her father’s house at 1, St. Mary Abbott’s Terrace, Kensington, moving to Warwick Gardens with her family after six years, the better to accommodate her expanding school.

The BDM says she taught at first with the manual alphabet and writing. In his biography of Alexander Graham Bell, Bruce says

Since 1864 the idea of teaching speech to deaf-mutes had grown in Melville Bell’s mind from an incidental possibility to “one of the prominent utilities of the system,” as he put it. This claim caught the eye of Bell’s former pupil Susanna E. Hull, who now ran a private school for deaf children at South Kensington. In the spring of 1868 Miss Hull asked Melville Bell for help following up on the idea. Thus, on May 21, 1868, Alexander Graham Bell first tried his skill at teaching the deaf, his pupils being two “remarkably intelligent happy-looking little girls” named Lotty and Minna. (Bruce, p.56)

The BDM article differs slightly – it says

on hearing of Prof. Bell’s “Visible Speech,” by which the deaf could be taught to speak, she went over to America, in one of her vacations, and studied this method, and for some years taught her children to speak in this way. When however, the late Mr. Arthur Kinsey was appointed Principal of the Ealing College, Miss Hull went to him, and studied the Oral system, and from that time – 1878, has been a strong advocate of the Pure Oral method; not only teaching her own pupils to speak but leacturing on behalf of the children of the poor all over the country, and always pleading for speech for the deaf. (ibid.)

Bruce says that she went to the U.S.A. and spent a month with Alexander Bell in Boston – this would have been in 1872 (Bruce, p.90). “During the school year a dozen or so pupils came to him, among them Theresa Dudley for two or three months, Susanna Hull from London for a month (somewhat to Bell’s regret, since she had “very little ear” for speech) […]” (ibid). Farrar says, “Another pioneer of the oral teaching in this country is Miss Susanna E. Hull, who had begun the private education of the deaf in 1862, but her method was more a combined than oral one, in which lip-reading was hardly recognised, and it was not until 1873 that she adopted the oral system in its entirety.” (Farrar, 1923, p.75)

Bruce says that she went to the U.S.A. and spent a month with Alexander Bell in Boston – this would have been in 1872 (Bruce, p.90). “During the school year a dozen or so pupils came to him, among them Theresa Dudley for two or three months, Susanna Hull from London for a month (somewhat to Bell’s regret, since she had “very little ear” for speech) […]” (ibid). Farrar says, “Another pioneer of the oral teaching in this country is Miss Susanna E. Hull, who had begun the private education of the deaf in 1862, but her method was more a combined than oral one, in which lip-reading was hardly recognised, and it was not until 1873 that she adopted the oral system in its entirety.” (Farrar, 1923, p.75)

Susannah Hull attended the Milan Conference, and in the address or paper which she read there, she said that when she began her work in 1863,

I was ignorant that so vast a number of our fellow beings were deprived of the sense of hearing, and I had no idea that so many institutions existed for the amelioration of their condition. All I then knew had been gathered from a short account of Laura Bridgman and James Mitchell, in Chambers’ Magazine. […] Then I heard through my father, a London Physician, of the miserable condition of a young lady, who by a succession of fevers had been left lame, maimed, deaf, and almost blind. No one could be found to educate this unhappy child, and my father was appealed to for advice and assistance. The slumbering desire of my heart awoke, and I gained permission to attempt the task. (p.69-70)

Told that she could “do nothing for those born deaf without signs”, and that she would have to enter an institution to gain that knowledge, she continued, “Nothing then remained but to teach without signs, or form them for myself.” She continues,

I enter thus minutely into my first steps to show how utterly unprejudiced I was to any system, how ready to adopt anything that could be to the advantage of my pupils.

With regard to signs, I must add, that, on looking back, I date a decline in my success in teaching language, from the time of the introduction of those signs. (p.71)

She explains more of the history of her methods, complains the the “Combined” system “injures the tone of voice”, and that “as the deaf are only to ready to think themselves the objects of detractive remarks, persons so taught will soon find out that their speech is peculiar, and be driven to use their voices less, to depend on silent methods more, and to prefer the society of the deaf.” (p.76)

Hull was a member of the Ealing Society for Training Teachers of the Deaf, and taught at the college’s school in order to gain an insight into Mr Kinsey’s use of the German Method of oralism, and to that end visited German Deaf Schools in 1883 with miss Yale of Northampton, Massachusetts (BDM p.103). She was one of the many who gave evidence to the Royal Commission on the blind, the deaf and dumb, &c., of the United Kingdom in 1886. In her testimony, on pages 255-9, she says (§ 7815) that she visited American Institutions in 1872 and 1873, and many German Institutions in 1883. Among other interesting things, she also says (§ 7884-5) that they had trouble at the college in recruiting men.

Susannah Hull wrote several pamphlets, some are listed below. She died on November the 24th in Sidcup, Kent, well regarded by her teaching friends, if the obituary in Teacher of the Deaf (thin as it is on biographical detail) is to be believed, but no doubt she was a disappointment to those who favoured manual education.

Clearly there are interesting avenues for research here, such as the teaching methods of early oralists as opposed to manualists (the Royal Commission report is useful here), a better understanding of the chronology of oralism and manualism, and following up on individuals from oralist and manualist backgrounds to examine as far as possible their stories after leaving education.

[Note: I originally wrote that there should be no ‘h’ Susanna, but she did sign her letter to the BDM with the ‘h’ so I have made a few corrections & added a little more information 7/2/2020]

Bruce, Robert V. Bell : Alexander Graham Bell and the Conquest of Solitude., 1973

Farrar, A., Arnold on the Education of the Deaf. 2nd edition, 1923.

Hodgson, K. The deaf and their problems. 1953

McLoughlin, M.G., A History of the Education of the Deaf in England,

Miss Hull’s Life Work, British Deaf Monthly, 1899, Vol.8, no.90, p.113

New Institute for the Deaf at Rochdale, opened by Miss Hull, Oldham Deaf-Mute Gazette, November 1907, p.45-53

Obituary. Teacher of the Deaf, 1922, 20, 161-64.

Our teachers: Miss Susannah E. Hull. British Deaf Monthly, 1900, 9, 84, 103, 121. (photo)

Susannah E Hull, works in the Historical Collection:

Lessons in intuitive language, from the pictures published by the Educational Supply Association…No.1, Industrious children moral series. London, Educational Supply Association, 18–?

My experience of various methods of educating the deaf-born: a paper written for the International Congress at Milan, September, 1880, p.69-84.

Teaching the dumb to speak: a health question for the working classes, a question for the rich. London, Witherby, 1884.

Letter to Miss Rogers on the International Congress held at Milan, Italy, September 6-11, 1880. Dated November 10, 1880 [Northampton, Mass: Clarke Institution, 1880]. Published as pp. 35-43 of the Appendix to the 13th Annual Report of the Clarke Institution.

A few words on the extension of our work. 18–?

I thought it might be of interest to add a list of her pupils from the 1881 census, the only one where she is listed with her students. I was unable to track her in the 1871 census and I suspect that she was travelling, though a careful search with variants of her name might find her, as transcribers often make errors. Most of these pupils will have been in the school when Hull attended the Milan Congress in September 1880.

| Address |

|

Surname |

Relationship to Head |

Age |

Estimated birth year |

Gender |

Occupation |

Place of birth |

|

Country of birth |

| Holland Rd 89 |

Susanna |

Hull |

Head |

38 |

1843 |

Female |

Instructor Of The Deaf By Vocal Speech |

Peckham |

Surrey |

England |

| Holland Rd 89 |

Clementina M. |

Hull |

Sister |

37 |

1844 |

Female |

Artist Oil Watercolor |

Peckham |

Surrey |

England |

| Holland Rd 89 |

Jessie M. |

Warden |

Pupil |

11 |

1870 |

Female |

Scholar |

(Brit Sub) |

|

India |

| Holland Rd 89 |

Phoebe G. |

Sandbach |

Pupil |

9 |

1872 |

Female |

Scholar |

Manchester |

|

|

| Holland Rd 89 |

Laura E.J. |

Gofton |

Pupil |

8 |

1873 |

Female |

Scholar |

|

Yorkshire |

England |

| Holland Rd 89 |

Beatrice M. |

Isleton |

Pupil |

9 |

1872 |

Female |

Scholar |

Camberwell |

|

|

| Holland Rd 89 |

Lilian M. |

Isleton |

Pupil |

7 |

1874 |

Female |

Scholar |

Caterham |

Surrey |

England |

| Holland Rd 89 |

Margaret O. |

Allan |

Pupil |

8 |

1873 |

Female |

Scholar |

(Brit Sub) |

|

India |

| Holland Rd 89 |

Chas.F. |

Coyney |

Pupil |

9 |

1872 |

Male |

Scholar |

|

Derbyshire |

England |

| Holland Rd 89 |

Cecil H.R. |

Jones |

Pupil |

7 |

1874 |

Male |

Scholar |

(Brit Sub) |

|

Venezuela |

| Holland Rd 89 |

Philip H. |

Francis |

Pupil |

8 |

1873 |

Male |

Scholar |

Addlestone |

Surrey |

England |

| Holland Rd 89 |

Henry |

Francis |

Pupil |

6 |

1875 |

Male |

Scholar |

Addlestone |

Surrey |

England |

| Holland Rd 89 |

Harry |

Hedgland |

Pupil |

8 |

1873 |

Male |

Scholar |

|

|

|

| Holland Rd 89 |

Mary |

Van |

|

42 |

1839 |

Female |

Governess Assistant (S M) |

London, London |

Middlesex |

England |

| Holland Rd 89 |

Lititia |

Amies |

Servant |

54 |

1827 |

Female |

Hsekeeper Domestic |

Norwich |

Norfolk |

England |

CENSUS

1911 Class: RG14; Piece: 3721; Schedule Number: 15

1881 Class: RG11; Piece: 28; Folio: 15; Page: 15; GSU roll: 1341006

1851 Class: HO107; Piece: 1614; Folio: 142; Page: 20; GSU roll: 193515

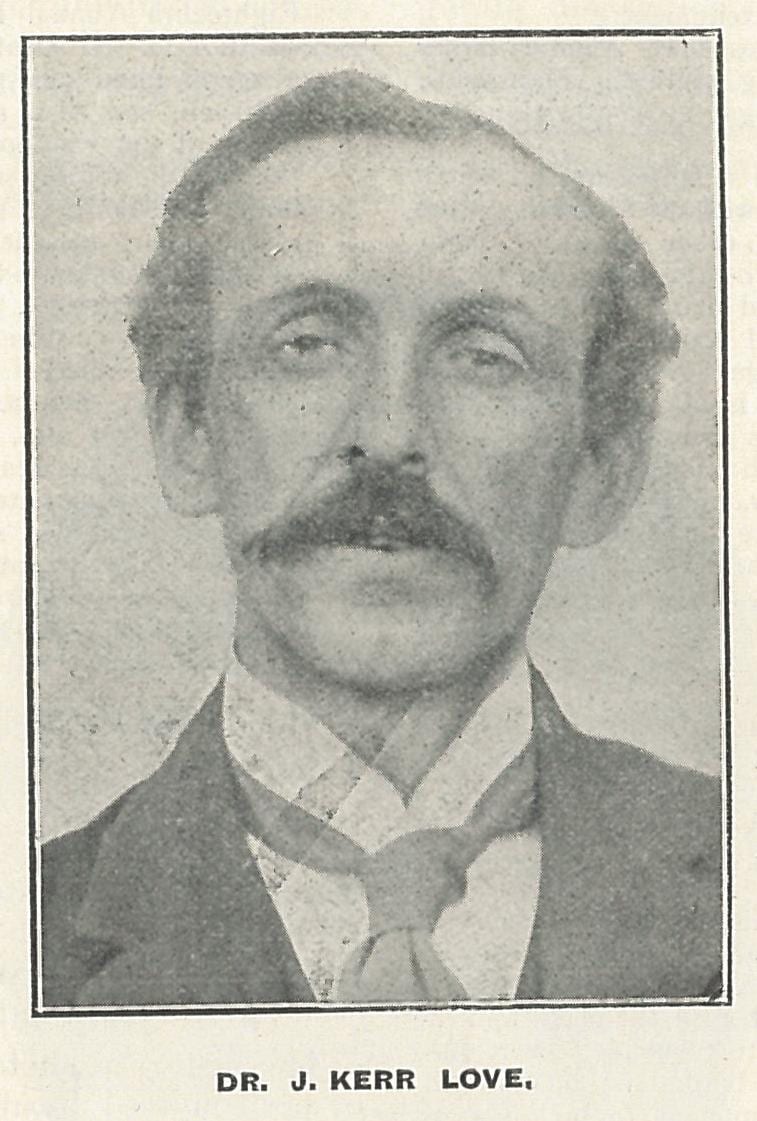

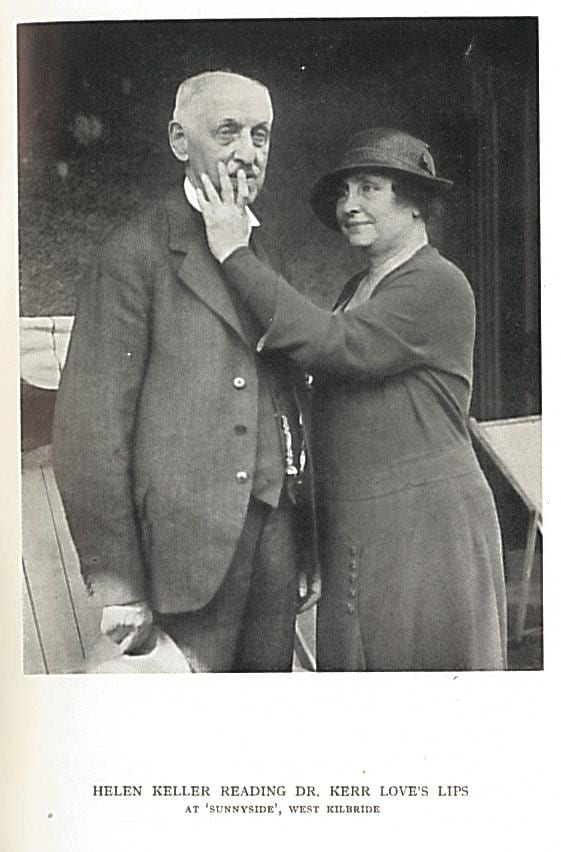

James Kerr Love was one of the leading British otologists of the early 20th century, but will be remembered more for his involvement with deaf children and his friendship with Helen Keller than for his surgical skills (BMJ, 1942).

James Kerr Love was one of the leading British otologists of the early 20th century, but will be remembered more for his involvement with deaf children and his friendship with Helen Keller than for his surgical skills (BMJ, 1942).

Kerr Love, J. & W.H. Addison. Deaf-mutism. 1904

Kerr Love, J. & W.H. Addison. Deaf-mutism. 1904 Close

Close