“Lamentable Death of a Medical Man” or how not to treat tinnitus – Joseph Toynbee

By H Dominic W Stiles, on 12 August 2016

Lincolnshire born Joseph Toynbee (1815-66) was a pioneer otologist. He attended school in King’s Lynn, then was apprenticed to William Wade of the Westminster General Dispensary, and later on at St George’s and University College Hospitals (Weir). In 1842 he became a Fellow of the Royal Society, surely one of the youngest fellows, for “his researches demonstrating that articular cartilage, the cornea, the crystalline lens, the vitreous humour, and the epidermal appendages contained no blood-vessels” (Plarr’s Lives of the Fellows). He was early on an opponent of the ‘aurists’ like John Harrison Curtis, writing letters to The Lancet on the matter. Curtis claimed that some deafness came “from a want of action of the ceruminous glands” – that is a lack of wax.

Toynbee belongs to the great set of scientists, like John Scott Haldane, who tried self-experimentation. In the case of Toynbee this did not end well. The Leeds Mercury begins its story on Toynbee’s end as follows:

Lamentable Death of a Medical Man

Yesterday afternoon a very painful investigation took place before Mr. C. St. Clare Bedford and a select jury at the New Vestry-hall, St. James’s, Piccadilly […] which was caused by the inhalation of chloroform and cyanic acid while prosecuting experiments for the advancement of science. […]

He was continually in the habit of making experiments on himself for scientific purposes and for the relief of suffering mankind (The Leeds Mercury).

His man-servant George Power described how he saw a patient in the afternoon for a few minutes. Shortly after another patient called & Power entered the room to find Toynbee lying with a piece of cotton wool over his nose and mouth. He thought he was asleep but removing the cotton wool realised that something was wrong then ran off down Savile Row trying to get another doctor to assist, to no avail. In the meantime Dr. Orlando Markham, a colleague from St. Mary’s hospital, had heard that Toynbee was in need of help, but arrived to find him dead. With another friend, Dr. Arthur Leared, they tried artificial respiration for half an hour. It seems from papers and a watch on his chairs, that he was trying “The effect of inhalation of the vapour of chloroform for singing in the ears so as to be forced to the tynpanum, either by being taken in by the breath through a towel or a sponge, producing a beneficial sensation or warmth”, and “The effect of chloroform combined with hydrocyanic acid”. He died on the 7th of July 1866, either from the chloroform, or the combination (The Morning Post, Leeds Mercury).

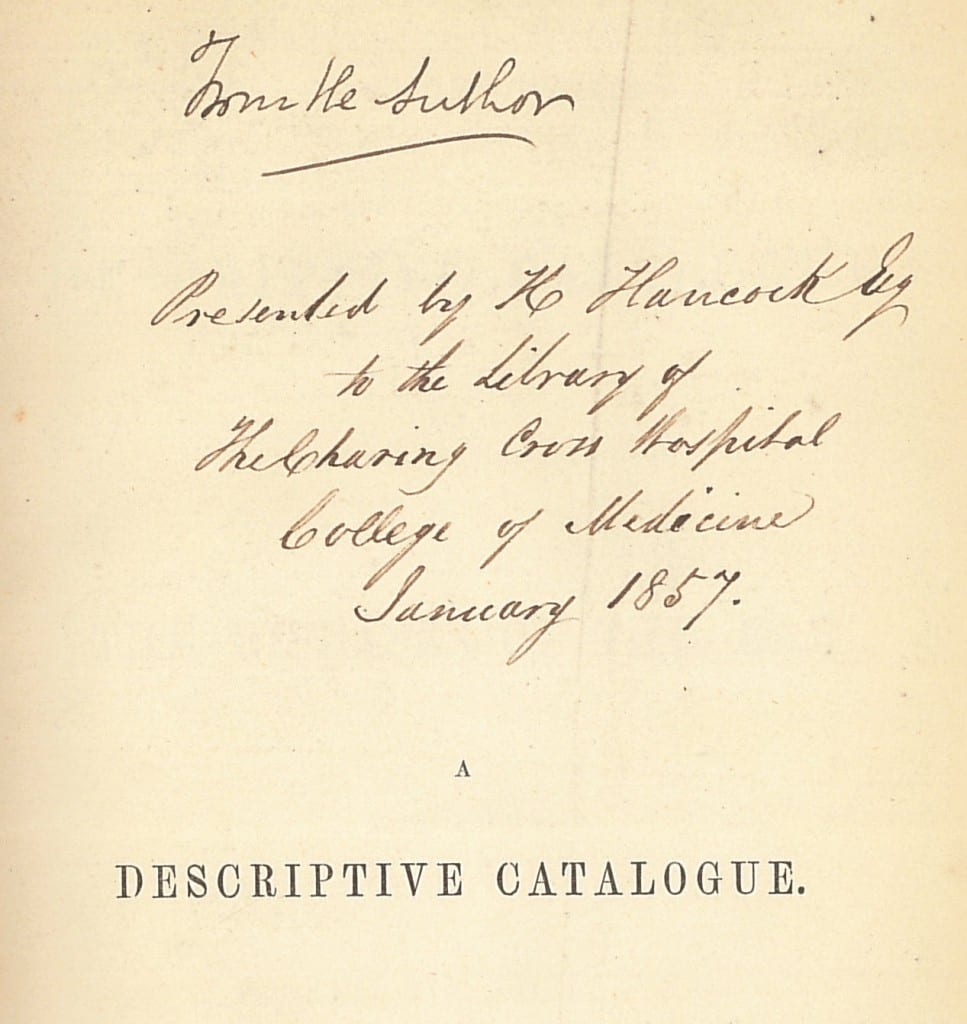

We have a copy of Toynbee’s A Descriptive Catalogue of Preparations Illustrative of the Diseases of the Ear in the Museum of Joseph Toynbee that must have been given by Toynbee as it is signed ‘from the author’, to Henry Hancock the surgeon, like Toynbee one of the original 300 fellows of the Royal College of Surgeons. He was not an ENT specialist, so perhaps that is why he then donated the book to the Charing Cross Hospital with which he had a long association. The Catalogue describes items in Toynbee’s collection, which ended up in the Hunterian but was lost during the war in an air raid. A page here shows that foreign bodies in ears are not new!

We have a copy of Toynbee’s A Descriptive Catalogue of Preparations Illustrative of the Diseases of the Ear in the Museum of Joseph Toynbee that must have been given by Toynbee as it is signed ‘from the author’, to Henry Hancock the surgeon, like Toynbee one of the original 300 fellows of the Royal College of Surgeons. He was not an ENT specialist, so perhaps that is why he then donated the book to the Charing Cross Hospital with which he had a long association. The Catalogue describes items in Toynbee’s collection, which ended up in the Hunterian but was lost during the war in an air raid. A page here shows that foreign bodies in ears are not new!

In the introduction he writes,

When, in the year 1839, I entered upon a systematic study of the diseases of the ear, the conviction was soon forced upon me, that its pathology had been almost entirely neglected. This conviction induced me to commence a series of dissections of that organ, which have continued up to the present time, and now amount to 1,659.

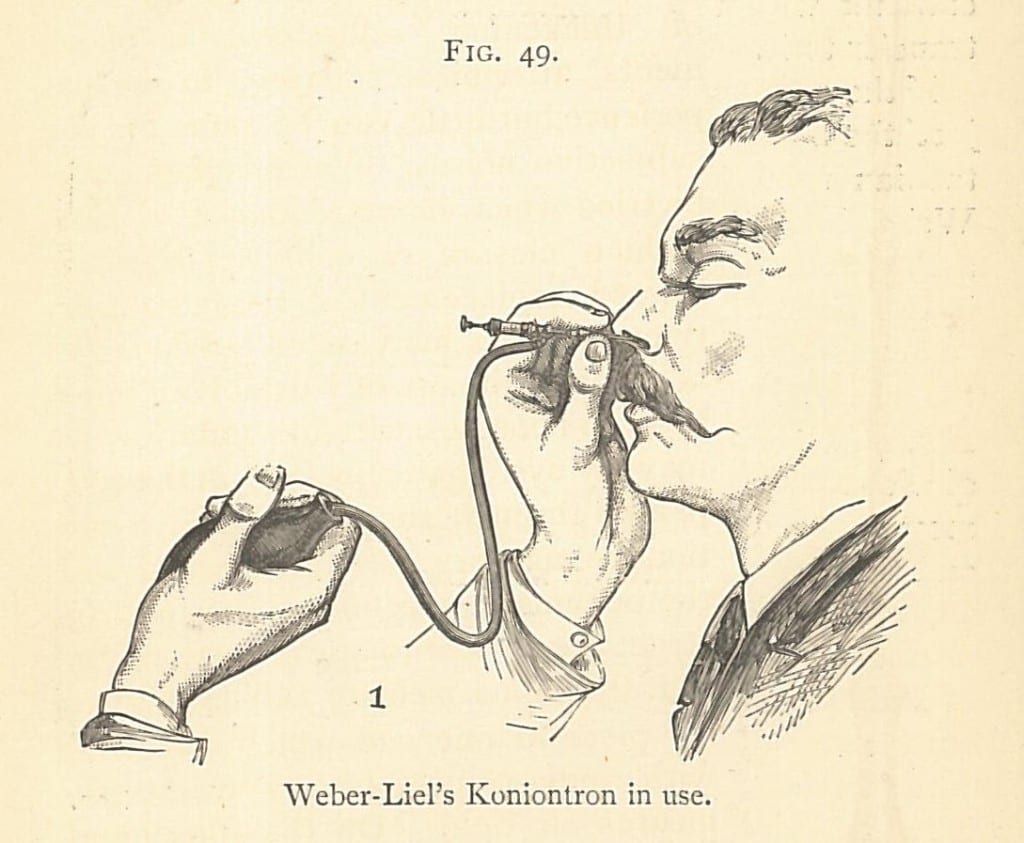

Above is a page from his book The diseases of the ear: their nature, diagnosis, and treatment (1868) which demonstrates use of a eustachian catheter.

An experiment in chloroform (from the website of our friend) Dr. Jaipreet Virdi-Dhesi, From the Hands of Quacks

Curtis J.H., Employment of creosote in deafness. Lancet 1838, 31 328-30

The Leeds Mercury (Leeds, England), Thursday, July 12, 1866; Issue 8813. British Library Newspapers, Part I: 1800-1900

The Morning Post (London, England), Wednesday, July 11, 1866; pg. 3; Issue 28886. British Library Newspapers, Part II: 1800-1900

Mudry A., The making of a career: Joseph Toynbee‘s first steps in otology. J Laryngol Otol. 2012 Jan;126(1):2-7. doi: 10.1017/S0022215111002465. Epub 2011 Sep 5.

Neil Weir, ‘Toynbee, Joseph (1815–1866)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/27647, accessed 12 Aug 2016]

Close

Close