Francis Green

Two months ago the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) revealed that the cuts in real wages in Britain over the last few years of stagnation have been the deepest since records began. And now figures collated by the House of Commons Library show that the cuts put Britain fourth from the top of Europe’s league of wage cuts, an unenviable record.

Still, some might say that many people have at least still got jobs. Three million unemployed was the forecast, but we remain still well below that. Perhaps those still in jobs are happy to have survived?

Far from it. The 2012 Skills and Employment Survey (pdf) shows that there has been a substantial drop in job-related well-being in recent years.

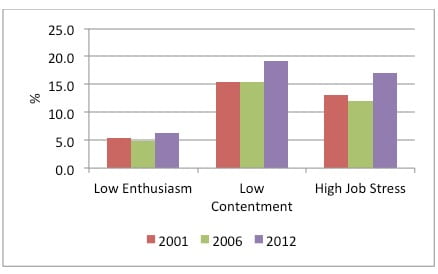

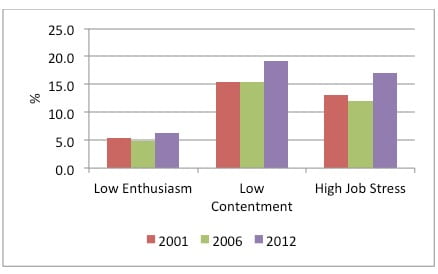

Since 2001 a research team has been periodically collecting nationally representative data. Using scales devised and validated by psychologists that capture the complex feelings that people express about their work, the trends in the index of “Enthusiasm” and in the index of “Contentment” can be plotted. These show that, whereas between 2001 and 2006 nothing much altered, between 2006 and 2012 there were some big changes. The diagram here shows how matters have gotten worse. It looks at the low end, giving the proportion of workers registering low degrees of Enthusiasm or Contentment below a certain threshold. As can be seen, there was a big jump in the proportion with low Contentment, from 15% to 19%, and a small rise in the share registering low Enthusiasm.

This means that there were many more jobs where people were reporting that their job frequently caused them to be worried, anxious, or depressed, and fewer where their jobs gave them contentment and enthusiasm.

We also used a measure of job stress, obtained by averaging responses on a 6-pt scale to three questions about the frequency of experiencing “worry about job problems”, “difficulty to unwind at the end of a work day”, or “feeling used up at the end of a work day”. We defined “high” job stress as where a worker responded “much”, “most” or “all of the time”. There was a large rise in the share of workers with high job stress, from 12% to 17%. This means that, across the country as a whole, there were nearly five million workers in the “high stress” category in 2012.

Why have people become unhappier at work? At the IOE’s LLAKES centre we have analysed the data to try to find out exactly what has been happening inside people’s jobs. We have found that part of the reason is that employers have been accelerating the pace of workplace change – including restructuring work organisation – and downsizing the numbers of other workers in the job. Such changes are detrimental for workers’ well-being. Another part is associated with increased work intensity, and employees’ decreasing sense that they have a say in matters that affect the way they do their work. Our worker respondents told us that they were having more meetings than before; but they were not being listened to as much.

A third part is down to the increased job insecurity that people are feeling. The risk of job loss is a source of stress in the workplace.

Yet fears in the workplace extend beyond just the fear of losing the job. They include the fear of being unfairly treated, and we have found that fears of unfair treatment (pdf) have risen dramatically since 2000, especially in the public sector. And in addition, as we now learn, most workers have been experiencing cuts in their pay, a change which is likely to have added to the feelings of depression and concern.

Of course, it is not all gloom and doom. Many employees have been able to do well enough in all sorts of jobs, despite the stagnating macroeconomic environment. What is clear, however, is that the detrimental effects of economic recession on well-being can be best ameliorated where employers afford their employees a good level of participation and involvement. The research shows that what matters most is direct empowerment of employees in their own jobs, but it also helps if employees can be involved in organisational matters.

Close

Close