Visibly invisible: you can always see me

By Xin Yuan Wang, on 24 March 2014

The Little Prince is probably the novel which I have read the most times. Each time I read it, I am warmly touched. Amid field work, I am reading it again. My favorite part is the conversation between the fox and the little prince, when the fox tells the little prince that meaning of ‘to tame’ is to ‘establish ties’.

“Just that,” said the fox. “To me, you are still nothing more than a little boy who is just like a hundred thousand other little boys. And I have no need of you. And you, on your part, have no need of me. To you, I am nothing more than a fox like a hundred thousand other foxes. But if you tame me, then we shall need each other. To me, you will be unique in all the world. To you, I shall be unique in all the world…”

“My life is very monotonous,” the fox said. “I hunt chickens; men hunt me. All the chickens are just alike, and all the men are just alike. And, in consequence, I am a little bored. But if you tame me, it will be as if the sun came to shine on my life. I shall know the sound of a step that will be different from all the others. Other steps send me hurrying back underneath the ground. Yours will call me, like music, out of my burrow. And then look: you see the grain-fields down yonder? I do not eat bread. Wheat is of no use to me. The wheat fields have nothing to say to me. And that is sad. But you have hair that is the color of gold. Think how wonderful that will be when you have tamed me! The grain, which is also golden, will bring me back the thought of you. And I shall love to listen to the wind in the wheat…”

I have to quote the whole lot what the fox said, not only because it is beautifully written, but also it reminders me of a recent talk between myself and my informant LX about QQ (social media) permission settings.

LX is a sweet factory girl who is 19-year-old. One day she complained that I was always ‘invisible’ (my QQ status) online, which is true. My QQ default setting is ‘invisible’ which means I can get QQ messages but my QQ contacts don’t know I am online when I log in. To be ‘invisible’ means I won’t be disturbed by other online contacts and it has become an accepted/applied strategy among my informants who have hundreds of QQ contacts to log in as ‘invisible’.

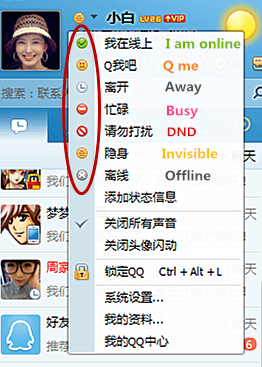

There are six online status of QQ (see the screenshot below): I am online; Q me (chat with me); Away; Busy; Do not disturb; and Invisible. For most people (90%) as long as they are online, the status is either ‘online’, or ‘invisible’, or ‘away’ with auto-response. The reason for being ‘invisible’ varies– the main reason is that people do not want to be disturbed or get involved in a conversation, however still want to view others’ Qzone (online profiles) and don’t want to miss any important message. ‘Do not disturb’ as a status is rarely used since people think that is rude.

I thought there were only six alternatives one can choose until LX taught me that actually there were some other ‘hidden’ options in the advanced permission setting. Right click any QQ contact’s avatar, on the pop-up select box (see screenshot below) there are a few options which enact different operations upon the certain contact, for instance: send instant message, send an Email (QQ offers email service which is the dominant email service my informant used), view chat log (one can check the local chat log, which is the chats that occurred on the current digital device or roaming chat log, which refers to all the chats under the same account occurring on different digital devices), put this contact on top of the contact list, edit the name (QQ names, in most cases, are not real names, as I mentioned in my previous report. As a result users will usually note the real-name if they know it), group the contact, delete the contact, report the contact (for online harassment), create a desktop shortcut, enter his/her Qzone, check his/her Tencent weibo (twitter-like service QQ offers) etc. and permission setting (see the screen shot below, blue highlighted). In the permission setting, there is one option that says “yin shen dui qi ke jian” (make visible to him/her in invisible status) which means the selected contact can always ‘see’ you even when you are in ‘invisible’ status.

I felt honored to realize that I am the second person who can ‘see’ LX when she is ‘invisible’ to others on QQ (the first one is her boyfriend).

“It is like you can always see me, and I am always there waiting for you, you know, very close and exclusive.”

LX further explained the significance of ‘visible invisibility’. In return, I set her as the first contact that can ‘see’ me when I am ‘invisible’, which made her very happy. Such mutual advanced permission setting reinforced our relationship.

‘To see’ is different from ‘to look.’ The latter happens all the time, however in many cases does not necessarily lead to the former. A senior manager of a local factory told me that the logic of assembly line is that humankind is a part of the machine. I asked him whether he personally knew any of the factory workers. Rather than answer ‘no’, he told me “it’s not necessary”. True, he only needs to know the machine. I am probably the first one (the weird one) who visited the factory workshop and paid more attention to the workers rather than the product, the building, and the machine.

“All the rural migrants are just alike” as some of my local informants put it. In this small town, in factory workshops, monotonousness on a daily basis is the grand narrative, eclipsing individuality. Most of the time, my rural migrant friends are ‘invisible’ to most people, even though they certainly did not ‘set’ themselves as ‘invisible’. Unfortunately unlike on QQ, the default ‘social’ setting of ‘invisible’ cannot easily be changed in their offline life. To live against such daily ‘invisibility’, LX’s skillful usage of QQ allows herself some ‘privileged’ visibility, and in consequence, an ordinary factory girl who is just like a hundred thousand other rural-to-urban migrant girls shall be unique in all the world, at least in the ‘virtual world’ created by social media.

Close

Close