Personal and public aesthetics: What I learned from my own visceral reactions in the field

By ucsanha, on 25 June 2015

Photo by Nell Hayes

At first, I couldn’t quite put my finger on it, but over the first several months in my fieldsite in northern Chile I began to realize that one of the reasons I never quite felt totally at home was that the aesthetics of the place never quite fit with my own sense of aesthetics. By aesthetics, I mean the effort and thought that people put into the way things look. In my fieldsite, a city of 100,000 inhabitants, I noticed this in public parks and municipal buildings, in both the inside and outside of homes, and in the way people dressed. It was not only an intellectual exercise, but a visceral feeling. If I wore the clothes that I was used to wearing, perhaps a dress or a fitted button down shirt, I felt as if everyone was staring at me because I was dressed with too much care. Perhaps they were right. There wasn’t really anywhere to go looking smart. The only bar in the city had cement floors, cinderblock walls, and heavy metal bands playing live every weekend.

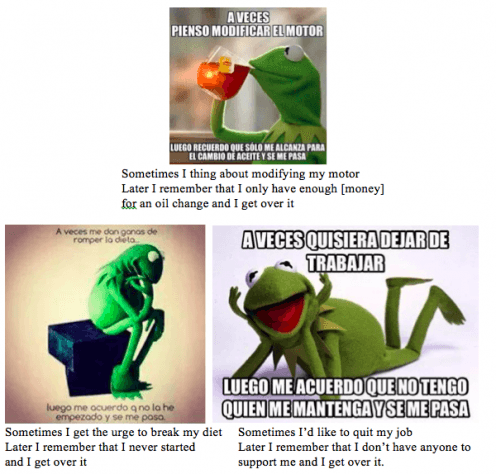

Over time I thought more about the sense of aesthetics in Alto Hospicio, and realized that while I had considered it entirely utilitarian at first, there was something more particular about it. The aesthetic was very much a part of the accessibility and normativity that prevailed in the city. The predominant aesthetic was not nonexistent, nor did it always privilege form above function or the “choice of the necessary” as Bourdieu calls the working class aesthetic. While many people clearly could afford to redecorate their homes or buy expensive clothing from the department stores in the nearby port city, their aesthetic choices leaned toward an appearance that was not too assuming. They didn’t flaunt or show off in any way. It was an aesthetic that was presented as if it were not one, because aspiring to a particular aesthetic would be performing something; a certain kind of pretension. Yet the aesthetic relies on deliberate choices to not be pretentious or striking; to be modest; to be unassuming. This aesthetic then not only predominated in the material world, but also online. Unlike in Brazil, where young people would never post a selfie in front of an unfinished wall, this was precisely the type of place youth in northern Chile might pose. While in Brazil this would associate the person with backwardness that contradicts the type of upward mobility they hope to present, in northern Chile this type of backdrop would add a sense of authenticity to the person and their unassuming lifestyle.

So, in the end, what began as a visceral feeling of discomfort in the field site, actually led to a very important insight. As I told academic friends many times during my fieldwork, “This place is a great site for research, but not at all a great site for living.” Fortunately, even some of the “not at all great” parts of about living in northern Chile helped my research more than I realized at first.

Reference

Pierre Bourdieu, Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgment of Taste. Richard Nice, trans. New York: Routledge (1984), pp 41, 372, 376.

Close

Close