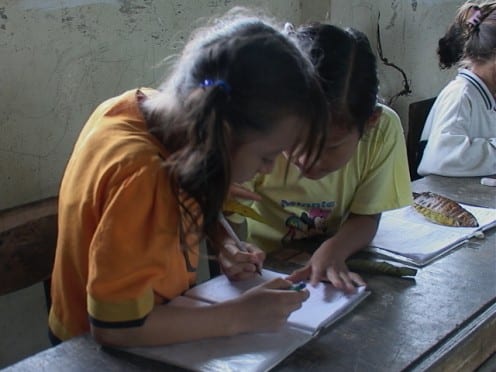

Nike cap, international sports shirt, colorful shades, and softdrinks – all items teens use to display financial progress. Photo by Juliano Spyer.

Fantástico, a popular Sunday TV news programme in Brazil, had two long pieces related to social mobility this past week. One was about teens learning to install braces themselves as they became a fashionable item. The other is about slums and how, in contrast to the common (external) view, residents now feel happy about living there (both links conduct to pages in Portuguese).

The first story is not framed as something related to social mobility (I will suggest the relation further ahead), but simply as another weirdness that became cool among teens and that can have serious consequences to one’s health. The other story is grounded in market research conducted with over two thousand people by Data Popular, a research institute specializing in investigating what has been called Brazil’s “new middle class”.

A distorted view

It is a good thing to see national news pieces such as the one linked above that question the social stigmas related to living in favelas. At the same time, I found the research to be problematic in the sense that instead of engaging with the usually complex and paradoxical social realities, it shows only positive aspects as a way of promoting this new consumer segment.

The data analysis reinterprets the idea of progress, bringing individualization and breaking social bonds. As an informant explains during the report, outside the slum, life is not just unsafe but also boring. Alternatively, in slums families progressed economically but retained the dense sociality and the networks of cooperation that existed before.

A more nuanced view

I have been living in a working class villa for the past 11 months; I wouldn’t call it a slum although it resembles one in many aspects including the aesthetics of the urbanization.

So signs of prosperity do appear all around but this prosperity is strictly combined with a great sense of competition. Part of consuming is only a way of showing off ones financial conditions. So buying a large TV is not necessarily a choice related to the desire to have that item, but also a form of informing the others about one’s economic progress.

Nobody wants to be seen as the lower part of the social latter; it is as if one’s reputation now corresponds to his or her ability to have and display wealth. If a neighbor buys a certain item, the others around may use all means possible to get the same thing, even if that results in spending the money she or he does not have.

The illusions of progress

This sort of competition does not necessarily make people work harder. In some cases, it has the opposite effect as individuals and families spend a lot of energy partying – because expensive loud speakers and the burning smell of barbecues are efficient ways of displaying one’s means.

But this competition brings even more serious consequences. The poorer families are being more violently confronted with their lack of conditions, and it is the youth from those families that show greater propensity to choose drug dealing as a way of acquiring respect and money.

Using braces, then, is yet another symbol of economic improvement as teenagers have become a sort of showcase for the family’s progress. Similarly, not having to work is equal to not having the obligation of helping in the household. But these changes are affecting the structures of families and society.

Junk food, branded clothes, and quick money

Using braces is as much a health problem as, for instance, the desire to consume highly industrialized goods such as chips and sugar drinks. Either one has the means to purchase junk food or it means their family are “struggling”.

Another problem is that most teenagers on my field site seem to look at schools as only a social arena; a sort of extension of their Facebook friend’s list. It is the place to display one’s means through wearing fashionable items. As an education coordinator told me recently, the poorest ones feel almost obliged to wear the most expensive brands.

Studying is not really something they see as being valuable. Having a diploma is maybe necessary, but learning is not clearly perceived as an advantage. Almost all my informants at this age group said they would much rather have a motorcycle – to show off and make quick money – than to have a professional degree.

So, yes, there is something significant happening in Brazil related to social and economic mobility. A large number of those that previously lived outside of the formal economy are now intensely involved in consuming. The problem is using statistics and research methodologies to simply support a claim that ultimately serves as a sales pitch and does not necessarily improve people’s lives.

Filed under Brazil, Fieldsites, Low income, Methodology, Parenting, Themes

Tags: branded clothes, Brands, Brazil, distinction, economic mobility, education, ethnography, Facebook, fieldwork, money, progress, social mobility, social networking, status

Comments Off on Glamorizing social mobility through market research

Close

Close