Using social media for teaching social media

By Tom McDonald, on 2 February 2015

QQ: China is just a click away (Photo: Tom McDonald)

This term our research team has been teaching a completely new Master’s module on the Anthropology of Social Media at UCL, with many of the students taking the module being from our fantastic MSc in Digital Anthropology.

In addition to incorporating the results from our own research in each of our fieldsites into our teaching, the students have been doing their own research on social media through mini-practicals taking place every week.

Last week, I wanted the students to experience QQ themselves, to get a feel for the platform, and to get a chance to see and think about how Chinese people interact on these platforms. In order to do this they joined a QQ Group and had a chance to communicate with English-speaking Chinese students in Beijing.

It was really interesting to see the two groups interact – albeit in very different ways – and it seemed from our conversations in the seminars that many people found examining the differences between QQ and non-Chinese social media platforms a useful starting point to think about Chinese practices in communication, social relationships and culture.

Seminar at SOAS Center for Media Studies

By ucsanha, on 21 January 2015

SOAS Main Building (Photo by SOAS CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

We are holding a public talk about our research at the SOAS Centre for Media Studies as part of their weekly seminar series. Feel free to come along and hear more about the Global Social Media Impact Study.

Time: 5-7 pm Wednesday 28 January

Venue: G3, Main (Old) building, SOAS (University of London), Thornhaugh Street, Russell Square, London WC1H 0XG. Map >

GLOBAL SOCIAL MEDIA – 9 ETHNOGRAPHIC STUDIES

This talk is by seven of the nine anthropologists who recently carried out nine simultaneous 15 month ethnographies on the use and consequences of social media, including two sites in China, one in India in Turkey and elsewhere. The study looks both at the nature of comparative and collaborative work for undertaking ethnographic research on new media. The presentations also consider some of the substantive results of the study and their plans for its dissemination.

For more information, visit the SOAS event page.

The myth of ‘un-edited’ photos on QQ albums of Chinese rural migrants

By Xin Yuan Wang, on 20 January 2015

In the analysis of visual content on people’s social media profiles, I found many of my informants (around 70%) have uploaded a great amount of un-edited photos to their online album. Furthermore, many of them told me that not only they themselves, but also many of their close friends and relatives all fancy uploading all the photos from their mobile phones or cameras to their Qzones. Even those who did not upload all the photos to their Qzone told me that it was a commonplace phenomenon among their QQ friends. ‘Un-edited photos’ is a “myth” which I have acknowledged a long time ago, however have never managed to get a satisfying explanation.

My curiosity about this myth climbed to the peak when one day I found that my informant Dawei just uploaded 248 photos about his one-day trip to a nearby sightseeing mountain area (1 hour drive from where Dawei lives). Dawei visited this place with his family (wife and son) and a family of his ‘lao xiang’ (literally means, old countryside guy, refers to people from the same original rural area) who came to visit his family during the national Day Festival (7 days holiday in early October). I further clicked into his album, there are 20 web pages of photos, and each web page illustrates 12 photos (see the screenshot above).

It seems that from the first moment they met each other to the last moment when they said goodbye, EVERYTHING (not only people but also food, car, trees, bridges, river, stones, etc) was recorded by photos. Plus, there are several photos of everything they encountered. For instance, the 12 photos on page 16 reconstruct the situation at that moment: They came across a stone bridge and people took three photos with similar pose, (blue photos) the orange photos were brook and plant under the bridge, the green one was the view from the bridge. And those six red ones were taken when people came across the bridge and met an artificial tree root with calligraphy on it.

As an ethnographer, who probably is supposed to take as many photos as possible and use photos to recapture some specific moments, I find my informants’ obsession of photography and their of visual data collection on the scene put me to utter shame. But why do people do this? They not only took hundreds of photos, but also uploaded ALL OF THEM online. I am more than confused.

I asked more than 30 people at my field site about the same question. And listed below are answers I received:

1. “Lan” (Laziness) – it is the first reason given by 90% of my informants without thinking. It seems that people regard selecting photos as a big trouble, and no one is bothered to spend some time on it.

“Well, I am lazy, you know, uploading all of them is just easy and convenient” as one put it.

2. “No Memory Limit online” – 60% of my informants added this as a second reason. Given most of my informants’ technology resource, this reason is very true and pragmatic. The digital terminals that most rural migrant people can afford are a Smartphone (cheap ones), and a digital camera in some well-off families. However both of these two digital terminals have limited memory space. The only place where people can store a great amount of digital material for free is their Qzone. So, let me put it this way: even though none of my informants has ever heard about ‘cloud storage’, their QQ have actually been used as ‘unlimited cloud disk’ for years even before the idea of ‘cloud storage’ was getting popular worldwide.

“Once a few weeks, all the photos on my mobile phone have to be deleted since there is memory limit”, as LXD said, he uploaded all the ‘have-to-go’ mobile photos to his QQ online album.

“I will upload all of them to my Qzone, so that people on the photos can go and view their photos” ZGY, also used QQ as a collective album which everybody has access to.

3. “They are all memories” – When have been asked “but I am still confused that why did people still keep those somewhat unnecessary photos?” 30% of my informants came back to the first reason ‘laziness’ and showed no intentions to further discuss this somewhat ‘stupid question’, however the rest gave me some more interesting reasons.

“Don’t you think those photos, no matter bad or good, were all memories?” WYL, asked me in reply. And she is the not the only one, more than 50% of people hold the opinion that photo is one of best forms of memories and will be valuable in the future.

“You may think they are unnecessary now, but all of them will be valuable after 10 years. So keep them.” CC, an 18-year-old girl, said in a grave and earnest way as if she has already experienced several ten years.

“My friend came to visit me all the way from his place of working; it is such a unique ‘yuanfen’ (karma). I would like keep all of them, so that when you look at them many years later, you can still remember the details thanks to the photos which have recorded your trip completely.” Dawei said, he is the one who has uploaded 248 photos about his one-day trip.

It seems that photos of each moment are regarded as the result of certain karma, no matter the photo itself is good or not. Once I was viewing one of my informants’ online albums with her and her friends, I found people were still so excited about their trip last year, and thanks to the hundreds of photos, people can even recalled what kind of beer they drank, and how many bottles they drank on that day. A consistent set of hundreds of photo worked like a time machine, creating a special space-time; pulling people back into that flow of time which has been locked in the photos. Also given the fact that for my informants going outside for tourist purposes (even a one-day trip) is such a luxury thing which only happened once or twice a year, people have all the reasons to cherish each photo which they took during the trip.

4. “That’s more confident and sincere” – XM, a 23 year-old factory worker, told me that she thought “people who select photos are not confident enough, because they tried to only illustrate the best part and hide the bad, however people who have no problem of uploading all of their photos are more confident about themselves since they would like to share even not perfect aspects of themselves with others.” XM’s opinion is quiet unique and interesting, even though no other person has expressed the exactly same opinion, many people agreed that they will take those who share ‘ugly’ photos of themselves as more sincere people.

“There are so many fake things in Chinese society, I hate hypocritical person, I am not a hypocritical person, so I will let everybody see the real me, at least online.” Apparently, ZF feels very proud of himself being sincere and he actually take the social media as the place to show a real him.

5. ‘Narcissism’ – YZY told me that “I knew I am not good-looking, but I am still a little bit narcissistic”. The reason of ‘narcissism’ is not novel at all since so many scholars have pointed it out that ‘narcissism’ was one of the main reasons of people’s photo uploading. However, my informants are a group of people who can rarely have people’s attention in their everyday life. For most of the time, they have paid attention to their managers, officers, and urban people etc. Thus social media has become somehow the only place where allows them to be narcissistic.

Of course there is no fixed answer for the myth of ‘un-editied’ photos. However various reasons given by my informants have definitely showed us how social media album can be used differently among digital-less and low-income population and the meaning of photos can be valued by different group of people differently.

The church or Facebook: Which is community-lite?

By Daniel Miller, on 16 January 2015

In The Glades it is very common for people to imply that organisations such as the church represent genuine communities which are now being undermined and replaced by social media such as Facebook which instead represent a kind of community-lite. But these same villagers produce evidence which is entirely contrary to this claim. As one parishioner noted `The church put on a Facebook page, a lot of people then did become friends with the church. Then I realised how many people are actually on there that I know and I see every Sunday. (Have you got to know them better now through Facebook?) Yeah. A lot better. Normally, you don’t really discuss what jobs they do or what social activities they do. You meet them in a church setting, talk about church related things.’ She then notes that thanks to Facebook she has come to realise who is related to who and who she knew about through other channels Another villager noted `When my husband had his heart attack last year I put on that he’d had a heart attack, it was amazing how many people sort of commented on it, wanted to know how he was, when he had his heart operation, quite a few of them were praying for him, that sort of thing. That’s nice cos I thought I’ve only ever known you through Farmville, interested enough to comment and think about it. A lot of the people I know are Christian people.’

In The Glades it is very common for people to imply that organisations such as the church represent genuine communities which are now being undermined and replaced by social media such as Facebook which instead represent a kind of community-lite. But these same villagers produce evidence which is entirely contrary to this claim. As one parishioner noted `The church put on a Facebook page, a lot of people then did become friends with the church. Then I realised how many people are actually on there that I know and I see every Sunday. (Have you got to know them better now through Facebook?) Yeah. A lot better. Normally, you don’t really discuss what jobs they do or what social activities they do. You meet them in a church setting, talk about church related things.’ She then notes that thanks to Facebook she has come to realise who is related to who and who she knew about through other channels Another villager noted `When my husband had his heart attack last year I put on that he’d had a heart attack, it was amazing how many people sort of commented on it, wanted to know how he was, when he had his heart operation, quite a few of them were praying for him, that sort of thing. That’s nice cos I thought I’ve only ever known you through Farmville, interested enough to comment and think about it. A lot of the people I know are Christian people.’

On many occasions people who might once have come directly to the clergy for support, post about themselves feeling depressed or betrayed by a friend on Facebook. It is only if they clergy have friended them on Facebook that they come to hear about these problems and can respond by calling round. A third woman likes the fact that her Facebook mixes the people she knows from church with others. She finds Facebook much more effective than going on websites as a means to reminder herself about church activities but also to share some of this news with others and possibly get them to thereby become more involved in church activities – since she works on several committees organising such events. She also does this by periodically using a hand knitted Christian `lamb’ to pose by religiously related images such as festive meals for photos she posts on Facebook.

What I found was that there was a core group to each church that were very close to each other and accord with our ideals of community. But for most of those who just attend services it is the church rather than Facebook that in some ways has been community-lite, because interaction was limited to church related issues. By comparison Facebook is much more holistic and makes visible the interconnectedness of people, especially people living in the same village, linking to other aspects of their lives. But more than that, these quotations suggest that for most people neither is sufficient, but the two work surprisingly well in tandem. If one is looking for interaction that approximates to our idea of community then it is the way Facebook builds upon going to church that seems most effective.

This would certainly not be true of more evangelical churches in places such as Trinidad or indeed perhaps in any of the other fieldsites. Elsewhere the church is highly integrated into people’s family and social life and barely leaves them alone. It may reflect another finding of this research which is that in The Glades the church, especially the established Anglican church, reflects a much more English tradition where it is quite circumspect about getting involved in people’s private lives. I recall a conversation with a vicar about whether even texting to remind people of an event might be considered too intrusive. So once again the issue seems to be one of Englishness, but in this case not the Englishness of social media but the much more established Englishness of the traditional English church.

Normativity on social media in Northern Chile

By ucsanha, on 7 January 2015

As many entries in the blog affirm, local cultural aspects are often reflected or made even more visual on social media. As I have written before of my fieldsite, there is a certain normativity that pervades social life. Material goods such as homes, clothing, electronics, and even food all fall within an “acceptable” range of normality. No one is trying to keep up with Joneses, because there’s no need. Instead the Joneses and the Smiths and the Rodriguezes and the Correas all outwardly exhibit pretty much the same level of consumerism. Work and salary similarly fall within a circumscribed set of opportunities, and because there is little market for advanced degrees, technical education or a 2 year post-secondary degree is usually the highest one will achieve academically. This acceptance of normativity is apparent on social media as well.

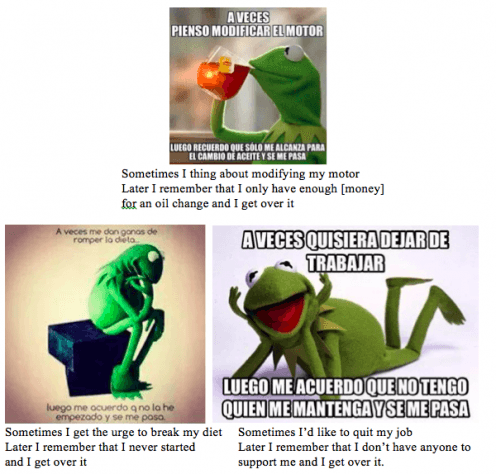

One particularly amusing example of this type of acceptance is especially apparent from a certain style of meme that overwhelmed Facebook in October of 2014. These “Rana René” (Kermit the Frog, in English) memes expressed a sense of abandoned aspirations. In these memes, the frog expresses desire for something—a better physique, nicer material goods, a better family- or love-life—but concludes that it is unlikely to happen, and that “se me pasa,” “I get over it.”

Similarly, during June and July of 2013 a common form of meme contrasted the expected with reality. The example below demonstrates the “expected” man at the beach—one who looks like a model, with a fit body, tan skin, and picturesque background. The “reality” shows a man who is out of shape, lighter skinned, and on a beach populated by other people and structures. It does not portray the sort of serene, dreamlike setting of the “expected.” In others, the “expected” would portray equally “ideal” settings, people, clothing, parties, architecture, or romantic situations. The reality would always humorously demonstrate something more mundane, or even disastrous. These memes became so ubiquitous that they were even used as inspiration for advertising, as for the dessert brand below.

For me, these correspondences between social media and social life reinforce the assertion by the Global Social Media Impact Study that this type of research must combine online work with grounded ethnography in the fieldsite. These posts could have caught my eye had I never set foot in northern Chile, but knowing what I know about what the place and people look like, how they act, and what the desires and aspirations are for individuals, I understand the importance of these posts as expressing the normativity that is so important to the social fabric of the community.

WhatsApp: A pain in the arse

By Juliano Andrade Spyer, on 4 January 2015

It is not uncommon for the people of Balduino to discuss sex. Even my least talkative informants enjoyed telling me about their love affairs outside their official relationships. So it is not surprising that loads of sex clips circulated through my informant’s smart phones’ WhatsApp exchanges. Yet I did not understand that a trusted female informant – that agreed to share her personal communication with me – constantly forwarded me clips of heterosexual anal penetration.

Most of the videos she sent me depicting sex had in common one element: they were low budged videos that displayed painful anal sex penetration.

Since I cannot show you those clips because of the nature of the content, I will briefly describe what is particular about them.

One clip shows the moment the male actor mistakenly misses the actresses’ vagina and penetrates her anus abruptly. The video is edited comically using slow motion to depict the ferocious reaction of the woman as she breaks from that predictable porn performance and, screaming, begins to attack her partner on that scene. There are also clips in which the women try to hide the pain by screaming in as if she was having an orgasm.

All these videos indicate that the women are putting up with those scenes for reasons that are not related to pleasure. They accept it, most likely because they are being paid as porn actresses, but they do not like it.

Why would adult heterosexual women be sharing this kind of content if it is not because it turns them on – as it clearly doesn’t?

My informant and her friends laugh at these scenes. For them, it is humouring the only channel that allows this kind of subject to be brought up. Laughing about these videos is a way to talk about the sudden change in gender relations in the village.

It was only in the past two decades that most women there began having the opportunity of developing a career and becoming financially independent from their male partners.

Men are no longer needed as before to provide money and protection for the family. In fact, women have become better adapted to the formal job market; they have studied more and are more productive than men according to various sources I spoke with. This change raises discomfort among men.

An informant told me her partner took away her birth control pills when she refused having sex late in the night (as she had to work early in the morning) as a way to punish her. As a mother she would again have to stay home and accept her dependence on him. Looking from this angle, the sharing of these painful anal clips exposes how difficult it has been for women and for men to negotiate new roles.

The conclusion may seem too obvious; but showing painful anal penetration clips may be just a way of agreeing that the men in Balduino are a big pain in their arses.

Does Facebook produce reality?

By Elisabetta Costa, on 31 December 2014

Facebook meme

Researchers of the Global Social Media Impact Study are currently writing a chapter about the visual material posted on social media. For this reason I’ve been carefully observing my friends’ Facebook profiles and I counted an incredibly high number of memes citing famous writers, poets, and philosophers. Differently from the Italian field-site (see Razvan’s last blog post) where highly educated people use Facebook to express their knowledge and abilities when these can’t be used in other ways, in Mardin young adults use Facebook to construct a well-educated, moral and virtuous self and make it visible to the others. As I’ve been told by many local friends, people in Mardin want to appear literate, wisdom, religious and moral, and they use social media to achieve this goal. In fact Facebook is also criticized for being used to construct an-ideal self that is quite different from the offline self. The discrepancy between the online and the offline was a discussed topic in Mardin, and it also emerged from my ethnographic observation.

On the public Facebook wall, people consciously post what they know is going to be under the gaze of others. The public Facebook wall in Mardin is a place to be observed and to be looked at. Young adults and and middle aged people don’t simply stage a successful character in that specific social context, but they perform a self that is imagined as continuously monitored, controlled and judged. In Mardin social media are spaces under surveillance, and people more or less consciously perceive themselves under the control and the gaze of others and of the State institutions.

In a region that has experienced decades of political violence and inter-ethnic conflicts, people’s traumatic experiences have led to the production of fears and suspicion towards the ‘other’, whether this is embodied by the State or by the social body, and whether the threat is real or not. These two levels, the State and the society, blend and reinforce each other. As result people tend to be aware of privacy settings, to be cautious about the material they share, and to post only what strictly confirms to dominant social norms. Surveillance is a productive force that generates specific performances and production of selves.

But probably the most interesting consequence of surveillance is that it makes the visible real. When the visible is monitored by the society and by its authorities, and for this reason it’s imagined as having real consequences, then it’s intended as real. It’s in this context of surveillance that the visible on Facebook becomes real. And this explains why many people in Mardin spend a lot of time and energy to accurately construct their idealized self on Facebook. In 1928 the two sociologists W.I. Thomas and D.S. Thomas formulated this theorem: “When men define situations as real, they are real in their consequences”. But we may also say that when one level of appearance is imagined as having consequences (and it does have consequences) then it becomes as real.

Why is Facebook so important for highly-educated unemployed people?

By Razvan Nicolescu, on 18 December 2014

The satirical blog spinoza.it is a most famous result of the phenomena I am describing in this post. With more than 500k followers on Facebook and more than 600k on Twitter, lines taken over by Italian celebrities like Roberto Benigni, and its own publication line, it is the result of the creativity of highly-educated Italian young adults who are outside the formal employment. The subtitle of the blog reads A very serious blog.

According to official data, the unemployment rate in South Italy drops dramatically with age and less dramatically with level of education. In 2013, unemployment was 51% for 15-24 year olds, 30% for 25-34 year olds, and then 16% for 35-44 year olds. In the same year, unemployment among 15-24 year olds was 56% for people with elementary or no studies, 54% for people with secondary school studies, and then to 50% for people with high school or vocational school. Similarly, for 25-34 year olds, unemployment rate was 36% for people with secondary school studies and 30% for people with graduate studies. It is after 35 years old when people with graduate studies find more work than those with lower studies.

Grano is by no means an exception. Many highly educated that live in the town could not find stable jobs until their late thirties and early forties. As I explain in my forthcoming book on social media use in South Italy, this is due to a combination of factors: firstly, and most importantly, there is no need in the local market for their specialisations: typically graduates in human sciences work on a temporary basis in food, tourism, and retail services. Secondly, specific social and economic conditions prevent people from undergoing professional reconversion or entrepreneurship: the Italian society structures individuals from very little ages to engage in, and be very faithful to, very separate cultural trajectories, such as a very defined difference between working class and public intellectuals. Thirdly, people who were educated for many years in prestigious universities in Rome, Bologna, or Milano, have a strong reticence to join the local system of networks and favours that could assure to many of them a good workplace, such as public servants.

Therefore, they are faced with the problem of how highly-educated people can do something lucrative while also making use of their very specific, and burning, cultural and social capital? The answer is through Facebook! This is more puzzling as most of these people have ambivalent feelings, or even genuinely hate this particular service.

Let’s take Bianca: she has 42 years old, is unemployed and has a masters degree in geography. She never thought she needed more than her basic Nokia phone to communicate, and joined Facebook just a few months ago. She did that mainly because she needed to be part of the Facebook group created by the small ecological association she is part of. Now, she enjoys posting about social, ecological, and sometimes political issues, and always takes brave and penetrating positions. By doing this, she established in Grano her reputation as a strong social and environmental activist.

Salvatore is 36 years old, holds a degree in Letters and never had a stable workplace. He is a quite active member of the local organisation of one of the few left-wing parties. Salvatore is renowned as an intelligent and witty character and loves to upload on Facebook comprehensive political comments and share news accompanied by smart remarks that usually attract a good number of ‘Likes’ or comments.

Indeed, just and Bianca and Salvatore, many highly educated unemployed who live in Grano started over the last couple of years to use Facebook quite intensively. This seems to be in relation to their need to build and advertise a certain cultural capital: all along the period of scarce employment, highly-educated unemployed have an acute need to express what they sense is their special knowledge – be that thoughts, skills, or talents – that is not requested locally. Thus, all these people with time on their hands just started to try articulate parts of this special knowledge on social media: they found different online niches and opportunities and also specialised themselves in different non-lucrative genres, such as, creating witty comments about current Italian politics, sharing more philosophical or poetic ideas, or sharing art and photography. Because of the constant exercise of these genres in the public space, some of these people find sporadic low-paid jobs in the hundreds of social and cultural events that take place throughout the year in the region of South Salento. Nevertheless, these jobs are particularly appreciated because they contribute to the consolidation of the kind of cultural capital these people aim for. In many cases, unemployed individuals set-up small environmental associations, vocational groups, or start to jointly promote the individual works.

This is possible in a setting in which their nuclear families and the local community provide the basic economic needs, as described here. As one woman in her early forties who never had a stable workplace suggested, if she was not present on Facebook, she would have felt she was completely dependent on her family: physically (she lives in a house owned by her family), educationally (her family supported her university studies for 8 years), and economically. Instead, Facebook was the easiest way to demonstrate to her family, and indeed to the entire community that she was not worthless. Then, social media was really the only place in Grano where she could practice her autonomy and critical thinking.

At the same time, most of the highly-educated unemployed adults enjoy positioning themselves out of the otherwise pervasive consistency between the domestic space and the online public sphere that I discussed elsewhere. They use social media in a relatively conspicuous way because they have to express their very particular ideas in the absence of a work environment suited to their training and knowledge that would absorb these. And it is this conspicuity that gives them the potential to form the next generation of local intelligentsia. It will be only in that distant and unsure future when they might recuperate the social confidence and standing that were shattered by the severe inconsistencies in the present society.

Social media Goldilocks: Keeping friendship at a distance

By Daniel Miller, on 9 December 2014

Many people seem to think that social media such as Facebook are principally a means to find and to develop relationships such as friendship. Clearly those people don’t try to study the English. I have just finished a chapter of my book on Social Media in an English Village and it has become increasingly clear that the primary purpose of some social media, such as Facebook, is rather more to keep people at a distance. But that needs to be the correct distance. Goldilocks is the ideal middle-class English story. Whether it comes to porridge or beds we, the English, don’t want the things that are too hot or too cold or too short or too long. We want the things in the middle that feel just right. So it is with many relationships.

Many people seem to think that social media such as Facebook are principally a means to find and to develop relationships such as friendship. Clearly those people don’t try to study the English. I have just finished a chapter of my book on Social Media in an English Village and it has become increasingly clear that the primary purpose of some social media, such as Facebook, is rather more to keep people at a distance. But that needs to be the correct distance. Goldilocks is the ideal middle-class English story. Whether it comes to porridge or beds we, the English, don’t want the things that are too hot or too cold or too short or too long. We want the things in the middle that feel just right. So it is with many relationships.

Yes, after Friends Reunited the early social media were often used to re-connect with people one had lost contact with. But as I heard many times this was also something one could regret, since often enough one was reminded of the reasons one hadn’t kept in touch in the first place. But that’s ok. If they become friends on Facebook you don’t actually have to see them. On the other hand you can satisfy your curiosity about what has subsequently happened in their lives as an entirely passive Facebook friend. Or if that feels a bit too cold you can add a little warm water to your bath with the occasional `like’.

When it first developed academics and journalists used to claim that the trouble with Facebook was that users couldn’t tell a real friend from a Facebook friend. Actually long before Facebook came into existence people would sit in pubs with one friend endlessly dissecting the last three encounters with a third party to decide whether that third party was or was not a `real’ friend. In fact the beauty of social media is that there are so many ways of adjusting the temperature of friendship. You can like or comment, you can have them in a WhatsApp group, you can private message them, you can send them a Snapchat, you can follow them on Twitter, you can acknowledge them in their professional capacity on LinkedIn, all on top of whether or not you phone, email and visit them.

Some of the best insights into the nuances of positioning come from discussions about the use of social media after a divorce, which might be your parents or relatives or again friends. Suddenly everyone is aware of what shouldn’t be shared with whom, and who might take offence if you are warmer to this side than you are with that side. Even in England we do sometimes actually make friends, but we then spend decades calibrating the right distance, judging exactly how much of a friend we want them to be and social media is just a wonderful way of getting things just right.

It’s all in the comments: the sociality behind social media

By ucsanha, on 2 December 2014

boys in the fieldsite hang out after school and look at Facebook on a mobile phone

As I begin to write my book about social media in Northern Chile, it’s great to see little insights emerge. One of the first of these insights is that interaction is essential to the ways people in my fieldsite use social networking sites. Facebook and Twitter are the most widely used, with 95% of people using Facebook (82% daily), and 77% using Whatsapp with frequency. But with other sites or applications, use falls off drastically. The next two most popular forms of social media are Twitter and Instagram which are used by 30% and 22% of those surveyed respectively.

So what makes Facebook so popular but not Twitter? My first reaction was that Twitter doesn’t have the visual component that Facebook does. This was partially based on the fact that many of my informants told me that they find Twitter boring. Yet Instagram is even less well-used than Twitter. And as I began looking more closely at the specific ways people use Facebook and Twitter, I began to see why they feel this way.

People use Facebook most frequently because they are most likely to get a response on that platform. In fact, this forms a sort of feedback loop in which people perceive that others use it more, so when they want the most feedback they use Facebook, which in turn keeps others coming back as well. As this cycle continues, people know that if they want their friends, family, colleagues, acquaintances, and even enemies to see something, Facebook is the place to put it. This is also what attracts older generations to use Facebook—if they want to see what is going on with younger generations, they join. But as their age-peers join for the same reasoning, they begin interacting with them as well. In essence, Facebook is the most truly social of the social media for people living in Alto Hospicio.

This desire for interaction is exemplified by the fact that far more important than writing statuses, or even posting photographs, memes, videos, or links to websites of interest, is the commenting in which people engage. It is not unusual to find a single sentence status update that has more than twenty comments. Many comments are positive and supportive. When a young woman posts a new profile picture, it will usually receive more than ten comments essentially expressing the same thing: “Oh [daughter/niece/ friend/cousin] you look so pretty and happy!” When someone expresses a complaint, like neighbours playing music too loudly, comments usually range from “How annoying!” to “Do you want to borrow my big speakers so you can show them your music is better?” These comments generally serve a function of staying in contact and supporting friends and family by simply reminding them that you are paying attention and care about them.

This type of cohesion has impacts beyond social media as well. Many friends of friends actually get to know one another through such comments on social media, so that by the time they end up meeting in person at a party or group outing, they are already familiar with one another, friendly, and if they’ve interacted enough on the same posts, may have already added one another as friends on Facebook. Thus, Facebook is not only a space for interacting with old friends, but making new ones as well.

Aside from helping me to understand how important sociality is to people in my fieldsite, this realization also serves as an excellent example of the ways quantitative and qualitative research support one another. Quantitative data from my survey alerted me to the fact that Facebook was popular not just for it’s visual uses. But I had to go back to my qualitative research to find out why exactly this might be. As I continue to analyze and write, I find that I keep bouncing between the two, reassuring me that without both aspects, this project would not have been complete.

For more on the confluence of qualitative and quantitative data, here are examples from England and Brazil.

Close

Close