‘Keeping it fair and honest’: how copyright exceptions can support your thesis, publications and teaching.

By Christina Daouti, on 22 February 2024

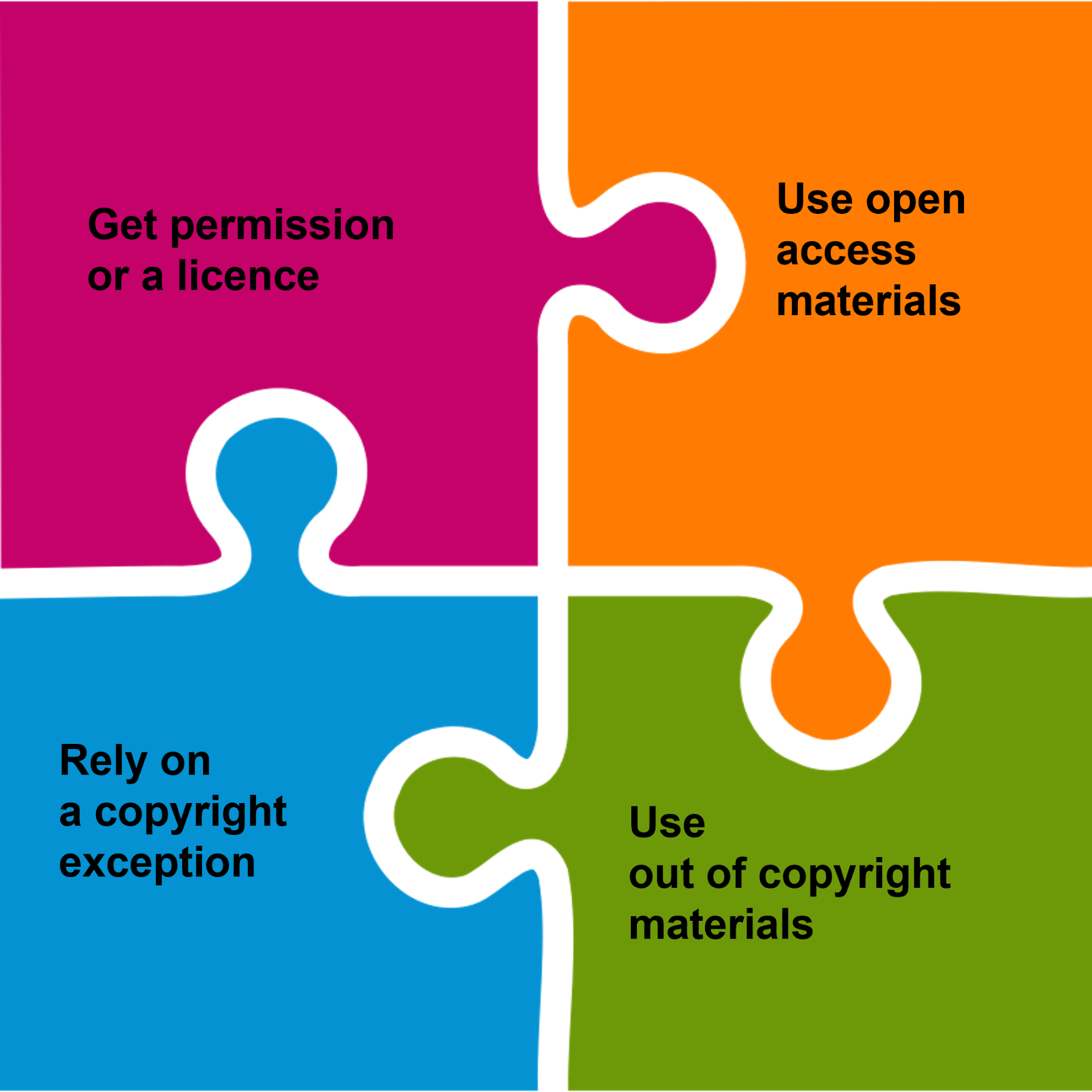

Square puzzle: Open Clipart, public domain. Text added by C. Daoutis.

Fair Dealing Week (26 February to 1 March 2024) is an annual opportunity to highlight copyright exceptions and how you may rely on them when using copyright materials in your studies, research and teaching. Although the main focus of the week is on ‘fair use’ in the US – quite different from ‘fair dealing’ – in previous years events were organised across countries with similar provisions, including the UK.

This year we will be marking fair dealing with a series of blog posts that discuss three copyright exceptions in UK copyright law that are subject to what we call ‘fair dealing’. We are also running a Q and A session on Monday the 26th of February at 2 pm at the UCL Institute of Education.

Register for the copyright exceptions Q and A

When using materials created by others (text, images, video etc) you normally need permission or a licence from the copyright owner. There are, however, other options to consider. In some cases, materials are in the public domain, either because copyright has expired or because the copyright owner has waived the copyright – as is the case in the square puzzle image used here. In other cases, materials are in copyright but are available under an open licence, allowing reuse under certain terms. Examples include open access articles, images available under a Creative Commons licence, and open source software.

In specific cases, you may also be able to use materials without permission by relying on ‘permitted acts’ (also known as copyright exceptions) which are defined in UK copyright law. Some of these exceptions are subject to ‘fair dealing’, which essentially means treating the materials in a ‘fair-minded and honest’ way. It is essential to understand how you can rely on copyright exceptions as this will help you use materials in a more flexible way. To help you test your knowledge, we have put together a 7-question quiz on copyright exceptions.

Take our new copyright exceptions quiz

Whether you are already a pro at fair dealing exceptions or would like to know more, look out for more copyright posts next week. We also hope you can join the Q and A on Monday!

Close

Close