Copyright myth #4: the appeal of set percentages.

By Christina Daouti, on 29 February 2024

Image by Freepik.

So far this Fair Dealing Week we have addressed a few common beliefs around what is ‘fair’ when using copyright materials. It is often thought, for example, that as long as the source is acknowledged or the use is non-commercial, it is OK to reproduce someone else’s work without permission.

This post is about the commonly asked question of quantity. How much from a work (e.g. book, article, thesis, blog post) can be reproduced in another work under ‘fair dealing’? It is often recommended that 5% (at most 10%) can definitely be used.

It is perhaps more accurate to think that, say, 5% from a source is likely to be fair in many cases, and use this percentage as a rule of thumb. However, this is still not helpful: it is not defined in the legislation how much can be used under fair dealing. How much is ‘fair’ is defined and shaped in court decisions. The quantity used (e.g. the number of extracts from a single source) and the proportion in relation to the whole original work, but also to the new work, should be taken into account. The amount used should be justified by the purpose, making related decisions a matter of judgement and risk.

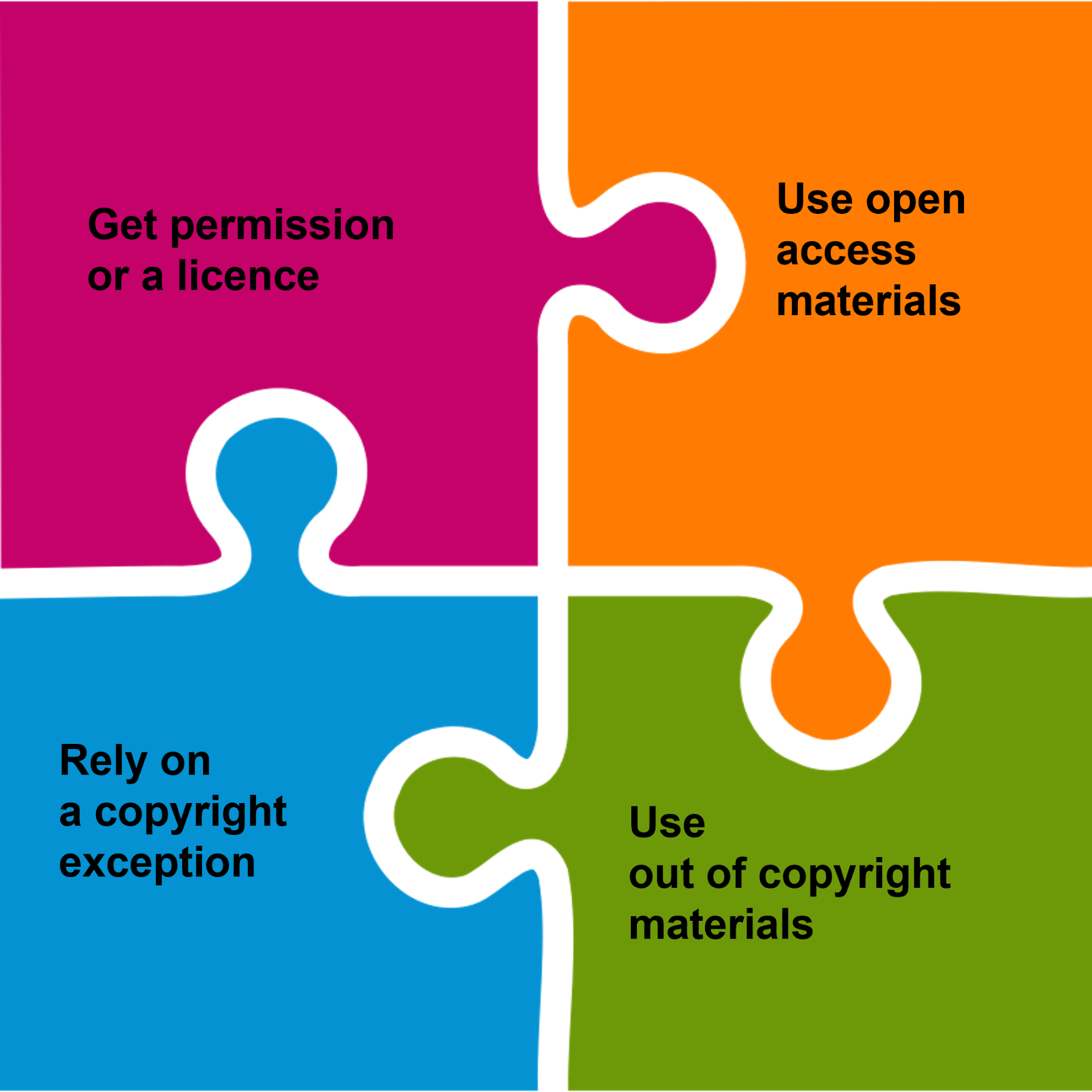

This is probably why we all tend to have an appetite for set percentages when relying on copyright exceptions – for example, like the 10%/one chapter rule specified in the CLA licence when using course materials. Our appetite for percentages is an appetite for clarity and certainty. This, however, is incompatible with ‘fair dealing’ as a concept. It is also likely to limit us, rather than help us, when making copyright-related decisions. In some contexts, it may be considered fair to use more than a prescribed percentage would suggest – and in other cases, what is deemed fair may be less. Developing a broader understanding of copyright as it applies to research and teaching helps make more nuanced decisions and ultimately be more creative when using copyright materials.

Learn more.

1. Complete our 7-question copyright exceptions quiz.

This is to help you understand copyright exceptions better: you can submit answers anonymously and we won’t be using your responses for any purpose.

2. Register for one of our sessions, on Teams or in person.

Our sessions cover copyright for PGRs, research staff and teaching staff; open licences; and publishing contracts. Sessions last up to 1 hour and 20 minutes.

3. Complete the Copyright Essentials online tutorial.

A self-paced, online tutorial introducing copyright in a fun and approachable way. It takes around 20-25 minutes to complete.

Further reading: quotation, criticism and review, copyrightuser website

Contact copyright support at copyright@ucl.ac.uk to ask a question, arrange an appointment or schedule your own training session.

Close

Close