Karol Tchorek’s studio

By editorial, on 3 March 2020

Magdalena Moskalewicz

On Tuesday afternoon, we visited the workspace of the late sculptor Karol Tchorek (1904-1985) and his son Mariusz, a known art critic and co-founder of Galeria Foksal, who died in 2004. The space is currently under the care of Mariusz’s widow, the British artist Katy Bentall—hence the current name, the Tchorek-Bentall studio— and is the only artist’s studio in Warsaw with the official status of a heritage site, which means it is under the protection of the city conservator.

An established sculptor already in the mid-war period—he received the silver medal at the 1937 World Exhibition in Paris—Karol Tchorek moved into this location in the early 1950s. This is when the previous building he had occupied, and where he’d run an art dealership called “Nike’s Salon” during the War, had been torn down to make space for the Stalinist rebuilding of Warsaw. Tchorek effectively built the studio, which is attached to the back of a nineteenth-century tenement building, beginning with the tiled floor he moved from the Salon, and created the unique atmosphere that it has till today. When we visited, the floor-to-ceiling window shone winter light directly on the decorative tiles and the multiple sculptures that populated the room in all its niches and corners. Other artifacts, documents, and photographs as well as historical furniture both added to the impression of an active, creative space and simultaneously provided a historical narrative about the studio and its residents.

Hosted by the custodians of the studio, Renata Wagner and her daughter Agnieszka, our group engaged in a conversation about the rebuilding of Warsaw in the aftermath of the World War II and Karol Tchorek’s involvement in it (the artist authored, among others, the iconic figure of mother and child at MDM, Warsaw’s Stalinist residential-commercial district); about the significance of the “General Theory of Place” co-authored by Mariusz Tchorek with other members of Galeria Foksal in 1966; and about today’s status of the historical sites like this one, when reprivatization and neoliberal policies in urban planning remove many of them from the Warsaw city map.

Holocaust Memory

By editorial, on 3 March 2020

Daniel Véri

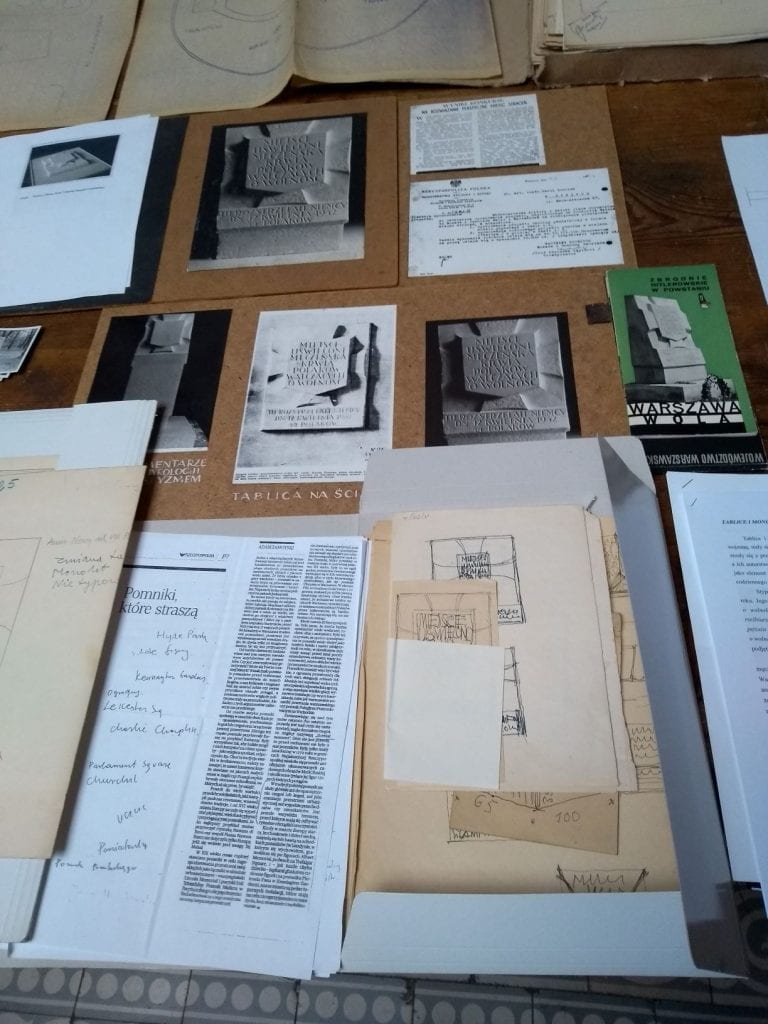

In Karol Tchorek’s studio a table is covered with material concerning the design and history of the so called Tchorek plaques. After the Second World War, people of Warsaw spontaneously started to commemorate in public spaces the various battles and executions that took place in the city during the Nazi occupation. A competition, organized in 1948, aimed to provide a standardized form for these initiatives.

The winning design was created by Karol Tchorek: on the memorial plaque a shield with a standardized inscription is placed in the middle of a Maltese cross, with an additional inscription below, explaining the specificities of each commemorated event. The general inscription translates as “This place is sanctified by the blood of Poles fighting for the freedom of their homeland.” The second inscription provides the details, including the number of victims, and also names the perpetrators, often worded as “Hitlerites”. Although according to the original concept for Jewish and Soviet victims a different type was designed, lacking the cross, in many cases the original form was used, with a shortened, standard inscription: “Honour their memory”. Many of these plaques are still scattered all around the city.

From the perspective of Holocaust-memory, they constitute an important, early initiative, even though their interpretation might be debated. On the one hand, the inscriptions separate “Poles” from “Jews”, thus creating an uneasy impression of Polish Jews being denied their “Polishness”. Yet on the on the other hand these plaques are rather straightforward, not shadowing the Jewish origin of the victims they aim to commemorate, as did for instance many Hungarian plaques at the time using the generalized expression: “victims of fascism”.

Power of Secrets

By editorial, on 3 March 2020

Corina L. Apostol

Karol Radziszewski “The Power of Secrets” at Ujazdowski Castle Centre for Contemporary Art in Warsaw is probably one of the best shows I’ve seen in Europe this year. It was a revealing experience having a special tour of the project with the artist himself and the art historian and critic Adam Mazur. The exhibition is the first large scale presentation of Radziszewski’s extensive art practice and it comes at a critical moment in Polish art history. The recent appointment of a director for the Center, Piotr Bernatowicz has been strongly criticized in Poland and abroad as a politically motivated decision that would go a long way to advance a far-right agenda in the arts. Indeed we experienced first hand the effects of Poland’s turn to the far-right even before we entered the exhibition when one of our colleagues was almost banned from having her baby with her, as Radziszewski’s work could only be viewed by adult visitors, given its queer subject matter. Nonetheless, after some tense negotiations with the guards, we were all allowed inside.

Karol Radziszewski “The Power of Secrets” at Ujazdowski Castle Centre for Contemporary Art in Warsaw is probably one of the best shows I’ve seen in Europe this year. It was a revealing experience having a special tour of the project with the artist himself and the art historian and critic Adam Mazur. The exhibition is the first large scale presentation of Radziszewski’s extensive art practice and it comes at a critical moment in Polish art history. The recent appointment of a director for the Center, Piotr Bernatowicz has been strongly criticized in Poland and abroad as a politically motivated decision that would go a long way to advance a far-right agenda in the arts. Indeed we experienced first hand the effects of Poland’s turn to the far-right even before we entered the exhibition when one of our colleagues was almost banned from having her baby with her, as Radziszewski’s work could only be viewed by adult visitors, given its queer subject matter. Nonetheless, after some tense negotiations with the guards, we were all allowed inside.

The artist acts as an amateur art historian, a collector of queer histories, and as a curator in this exhibition (the show also includes works by Ryszard Kisiel, Natalia LL, Libuše Jarcovjákova, Wolfgang Tillmans and the collective General Idea). The show opens with quotes and drawings from his childhood, combining fairy tales with fantasies and memories. The histories he is recuperating are very compellingly presented in the show, which mixes political events with intimate stories, private narratives, and public ones. Part of the exhibition is dedicated to queer heroines and heroes (Taras Shevchenk, Wojciech Skrodzki and Ewa Hołuszko) as well as other prominent figures from Polish history whose queer identities have remained hidden. These are shown as part of the Queer Archives Institute, an informal institution created by the artist focused on the ongoing research of queer histories in Central and Eastern Europe.

Radziszewski’s work can be thought of as a practice of self-historicizing and also part of a larger movement in our field to write overlooked or erased queer art practitioners and their stories into art history, which compels us to rethink what counts as art historiography. Due to the policing of queer lives and queer art in Poland it, unfortunately, seems that many significant works and artists will remain more private or hidden away in personal archives rather than in major museums in the country. Which is what makes “The Power of Secrets” even more significant today.

Church Art in the Palace of Culture and Science

By editorial, on 3 March 2020

Ivana Bago

First thing in the morning was the ideal time to visit the famous Palace of Culture and Science, built in 1955 on the model of the “Seven Sisters,” a group of skyscrapers built under Stalin in Moscow. We were there to visit the exhibition and storage spaces of the Studio Teatr Gallery, but we also used the opportunity to ride the elevator and get a 778-ft-tall bird’s-eye view of Warsaw. Following the tour of the Palace and the gallery storage spaces, where we had the privilege of seeing mannequins used in the theater plays of Józef Szajna, who also directed STUDIO Theater during the 1970s. This was also the time when the STUDIO Theater Gallery was founded, as we later learned in the presentation by the gallery director, Dorota Jarecka, held in the exhibition space.

The presentation on the history and the program of the gallery was followed by a seminar on Polish art of the 1980s in Warsaw, with Dorota Jarecka and Piotr Rypson. One of the central topics of the conversation was “church art,” or a series of exhibitions that took place in churches during the post-Solidarity 1980s – an exotic and surprising topic for all who had earlier not been acquainted with the phenomenon. Jarecka, an art historian and curator who did research on the topic, protested the term “church art,” finding it misleading: not all artists who exhibited at churches were religion, and the (Catholic) church today is not what it was in the 1980s. In Jarecka’s view, what is intriguing about the phenomenon is the way that artists negotiated the exhibitions with the church and parishioners, at the same time seeking to maintain the autonomy of art. Rypson, art historian, writer and witness of the era, disagreed to an extent, reminding us that there were artists who were also genuinely interested in Christianity, as well as alternative forms of spirituality, towards which a number of priests and parishes were also open at the time. Rypson himself was more drawn to alternative culture and told us very compelling stories about the Remont gallery, a student-run space that also housed punk concerts and distributed zines, as well as a number of other relevant spaces and events in Warsaw, and beyond.

Mapping Łódź Eighties

By editorial, on 3 March 2020

Juliane Debeusscher

Tomasz Załuski’s comprehensive presentation “Lodz in the 1980s – The Local is Networked” immersed us into the atmosphere of the local cultural scene of the decade. With the introduction of martial law on December 1981, artistic initiatives sought to explore a “third way” far from any political, religious and even artistic authority – and, possibly, ridiculing it. The idea of “embarrassing art” invented by Łódź Kaliska epitomises this attitude of anarchism, surrealism and self-mockery, promoting art as “unfruitful, insignificant, stupid, uninteresting, unconstructive, incoherent” (and so on…).

Particularly interesting to me were the critical discussion on the authoritative position and legacy of the neo-avant-garde of the 1970s and the emblematic phenomena of the “Pitch-In-Culture.” Understood primarily as a means of collecting money for alcohol (vodka) and food, it manifested itself through gatherings, performances, screenings and exhibitions in private locations, like the Attic (Strych) run by Łódź Kaliska. While many projects focused on black humour, absurdity and excess, they also reflected a sense of community, self-organisation as well trans-generational and transnational cooperation that could provide a ground for a fruitful comparison or dialogue with other Eastern European initiatives of that time.

Such communal experience was not devoid of agonistic dimension, as Tomasz remarked. No consensus around common principles, but rather a particular form of “atomization” – also evoked by Piotr Rypson in Warsaw – that allowed these practices to survive under martial law and even be continued in other forms after the system’s change in the 1990s.

PRL – GDR

By editorial, on 3 March 2020

Constanze Fritzsch

A local art history and mapping of the art scene of a single city can be very problematic because of flattened art history that proposes only a very narrow narration. Nevertheless, as in translocal, comparative art history the scale plays an important role, the art history of a region or a city may permit a comparison that otherwise would not be possible as in the case of Poland and GDR. A Polish, East-German comparison is especially challenging because of the lack of significant translocal exchanges or networks as well as different chronologies due to different socio-political settings. The presentation of the Łodź art scene of the 1980s by Tomasz Zaluski provided a common ground for parallels of the art scenes of Łodź, Leipzig and Dresden beyond a strict chronology and without neglecting the very specific context. Parallels can be drawn and studied between the necessary irony and sarcasm to deal and face an over-ideologized everyday life and a disastrous economic situation in the exhibitions of the Eigen + Art Gallery or the performances of the Auto-Perforations-Artisten. As a result, in parts of all three art scenes the art practices are characterized by a disillusionment with the socialist project and a network of private initiatives, as the production of Super film in Dresden or the different groups around A.R. Penck shows. Moreover, the church serves not only as a host for art events, but also as a spiritual resource and biographical background for artists like f. e. Else Gabriel (member of the Auto-Perforations-Artisten) as well as a platform which would allow a forum to debate and communicate. This analyze of similarities can be embedded in a Europe-wide art history of tendencies, characteristics and issues of the art of the 1980s.

Sounds of the Underground

By editorial, on 3 March 2020

Johana Lomová

In his talk Daniel Muzyczuk (a curator at the Muzeum Sztuki in Łódź) presented research behind two exhibitions that he had prepared together with David Crowley. Sounding the body electric mapped connections of sound and visual culture in Eastern Europe, and Notes from the underground concentrated on the underground culture where music and visual arts has merged. A few important issues came out during the presentation. Besides the regional interest of both curators in Eastern Europe that included Russia (St. Petersburg has a special place in their research), we have been introduced to a different time frame for research of culture under socialist politics as the second mentioned exhibition ended in 1994. In this way Muzyczuk and Crowley were able to show how the underground culture reacted to a new political regime. A rather provocative thesis of connection between neoprimitivism and right-wing radicalism opened a discussion and our attention was drawn towards a concept of overidentification, politics of self-representation and other. The blurriness of the boundary in between official and unofficial art (or rather the uselessness of this division) was illustrated by the fact that a number of nonconformist artists did have an artistic licence.

Deterritorialising Modernity

By editorial, on 3 March 2020

Asja Mandić

After the group seminar and thought-provoking presentations in Museum Sztuki/MS 1, the group headed to the newest museum branch, MS 2 for a guided tour with Joanna Sokolowska who showed us the museum collection through the Atlas of Modernity exhibition.

The venue, located inside Manufactura, the former 19th century factory complex, now the city’s main touristic hub, associates the museum to the world of spectacle, entertainment and leisure culture of the post-industrial consumer society. Enveloped in the redbrick, it does retain the image of the mill factory, nevertheless the interior gallery spaces are somewhat conscious of the modern white cube. Atlas of Modernity reflects a similar mode. Modernity, the ideas about it and the experience of modernity in the 20th century art as well as its traces in recent artistic practices, as the main conceptual framework of this show, directs presentation of national as well as international pieces from the collection. Rather than providing an historical overview of modern art in Poland, the exhibition pinpoints several themes, like the points in an atlas or a map, among which are machine, progress, capital, revolution, emancipation, but also autonomy and the self. Arranged in a manner to correspond to this web of ideas or fragments of modernity, the works from various media, time periods as well as stylistic features, make very interesting juxtapositions.

This inspiring museum visit brought us back to some questions addressed in our previous discussions, such as relationship between socialism and modernisation, issues of socialist modernity… as well as to the notion that “socialism and modernity do coexist”. (Tomáš Pospiszyl)

Galeria Wschodnia

By editorial, on 3 March 2020

Hana Buddeus

After an intensive day spent at Muzeum Sztuki, we were happy to go out and experience the reality of the post-industrial atmosphere of the city of Łódź. During a visit to the Galeria Wschodnia, we were presented with an opportunity to zoom in on the image of the 1980s Łódź art scene, which we had been introduced to through the presentations that morning.

The gallery – established in the early 1980s and one of the oldest artist-run spaces in Poland – is still situated in the same location, an old apartment building on Wschodnia street. It consists of two gallery rooms, a guest room used by artists in residence, and a kitchen, the place of social interaction, under the reign of a cat, Benek, who has experienced the gallery’s entire long history. Adam Klimczak, one of the two artists who has run the space from the very beginning, was kind enough to not only show us the current exhibition but also let us enter the kitchen, where he recounted some of the adventures connected to the place. A recently published book Galeria Wschodnia. Dokumenty 1984-2017 / Documents 1984-2017, edited by Tomasz Załuski, confirms (and reassesses) the historical importance of the space.

Museum in Process

By editorial, on 3 March 2020

Agata Pietrasik

During our visit to Muzeum Sztuki in Lodz the Confrontations group had a chance to see the highlights of the collection of Muzeum Sztuki, as well as reflect on the history of the institution. We began our tour with visiting the most famous part of the museum – the Neoplastic Room designed by the pioneer of Polish avant-garde Władysław Strzmiński. Daniel Muzyczuk, curator at the Muzeum Sztuki, presented the complicated history of the space, which was opened in 1948, destroyed only two years later due to introduction of socialist realism, and eventually re-created in 1960.

We also discussed how museum tries to activate the space with interventions by contemporary artists. We also paid a visit to the Museum’s library, which is one of the oldest art libraries in Poland and possesses many unique books and documents. Some of them were on display. For example, we could read a letter to Strzemiński written by his Jewish colleague Jozef Kowner. The letter resonated strongly with the earlier lecture by Luiza Nader.

Our group was taken away by the visit to museum’s storage rooms, where we could see a fascinating combination of artistic practices: avant-garde artworks of Karol Hiller, socialist realist paintings by Wojciech Fangor and rarely exhibited 1949 Strzeminski’s sketch for the Egzotyczna cafe in Lodz.

Touring Muzeum Sztuki

By editorial, on 3 March 2020

Marta Zboralska

At Muzeum Sztuki in Łódź, Maciej Cholewiński introduced us to the institution’s library collections. They include the personal correspondence of key figures in twentieth-century Polish art, a selection of which was on display inside a dedicated vitrine. Maciej also hand-picked other archival materials relevant to the interests of our group – such as the pamphlet issued by the Łódź branch of Solidarity for Construction in Process, the 1981 exhibition discussed during the presentations the day before.

We then had the privilege of being shown around the museum’s open storage by Paulina Kurc-Maj. Few of the paintings we saw were straight-forwardly Socialist Realist, instead complicating the coherence of this category. Some of the period’s inherent contradictions were exemplified by Władysław Strzemiński’s study for a wall relief entitled Colonial Exploitation, made during 1949: the year that both followed the opening and preceded the destruction of the famous Neoplastic Room. As we toured the Room’s reconstruction with Daniel Muzyczuk, we had the opportunity to reflect on the historical intersections of figuration and abstraction – or the plasticity of this very dichotomy.

Complexity

By editorial, on 3 March 2020

Gregor Taul

After a week of inspiring meetings and discussions we sat down for the closing session to phrase some of the overriding questions we had been so far trying to find answers to. The following list of inquiries, by no means conclusive, offers also a practical introduction to our last gathering in Paris and London: Where is transnational art history being done? What is the relationship between national and transnational art history? How to come up with meaningful terms for comparison? Are we looking for similarities or differences? Who has the right to write comparative art history? Do we actually need national art histories? How to avoid simplifications? How to avoid the appeal of the Other? How important are political events for comparative art history? What is the role of art museums and national collections in telling transnational art histories? Which museological approach is most up to date?

Exchange Gallery

By editorial, on 3 March 2020

Pavlína Morganová

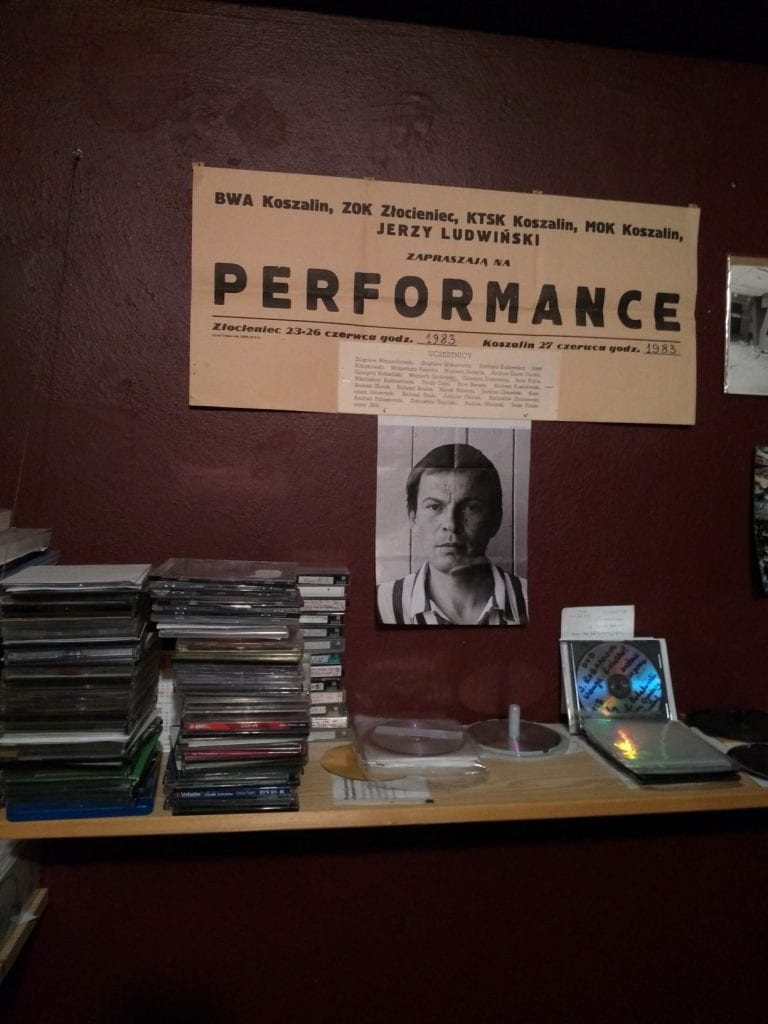

As Tomasz Załuski put it in his essay On Art History and Its Advantages for Living, Józef Robakowski is a one-man institution: he is an extraordinary multimedia artist, gallerist and archivist at the same time. In 1979 he founded along with Małgorzata Potocka The Exchange Gallery. Located in their studio apartment on the 9th floor of the Łódź tenement building called Manhattan, it invited artist to exchange ideas in original presentations as well as all kinds of textual and visual archival records.

Now into his 80s, the artist accepted the group on Friday evening and generously answered all our questions about the history of the Workshop of Film Form, The Exchange Gallery and his own work. I was especially interested in the series of his famous films From My Window shot from the windows of the apartment from 1978 until 1990s. Robakowski started to film the series on film camera and later in 1980s switched to video camera. His apartment is not just witness of many artistic experiments, exchanges, exhibitions, but also the site of creation of his extraordinary audiovisual pieces.

Breaking the Rope

By confrontations, on 5 November 2019

Picking up the threads of the conversations about East European art history from the first session of Confrontations, the focus of the initial seminar at the Academy of Fine Arts in Prague was on attempts to locate East European art within global art history. This entailed discussing the legacy for East European art of the tripartite division of the Cold War, the relation of East European art to other global non-Western art regions and collectively analysing methodologies and curatorial approaches to reframing East European artistic identity three decades after the fall of communism.

Taking sides on the issues of whether belonging to the Second World during the Cold War was a privileged position for East European art, is East European art closer to the Euro-American axis or to the art histories of the global South, and how relevant is the decolonial project for the region, again saw the engagement of participants in a symbolic Tug of Art History. The impassioned position-taking on art historical dilemmas this time ended up breaking the rope.

Discussions that arose confronted the theorisation of decoloniality with the actual situation on the ground of East European art history. There were calls to pluralise decolonialisms, warnings about the dangers that the decolonial project could turn into nationalism and a desire expressed for political, ethical and microhistorical approaches that would allow for other narratives to emerge.

(Maja & Reuben Fowkes)

Socialist Art

By confrontations, on 5 November 2019

After Pavlina’s fruitful introduction to the various Confrontations exhibitions throughout the socialist period in Czechoslovakia and beyond, we continued the morning session with a lecture on socialist art by Tomáš Pospiszyl, Czech critic, curator and art historian. In 2018 JRP Editions published Pospiszyl’s monograph An Associative Art History: Comparative Studies of Neo-Avant-Gardes in a Bipolar World which aimed to locate East European postwar art in global history. Speaking at his home institution – Pospiszyl is a lecturer at the Academy of Fine Arts in Prague – he gave a most amiable overview of the tasks for the study of East European art during the socialist era.

After Pavlina’s fruitful introduction to the various Confrontations exhibitions throughout the socialist period in Czechoslovakia and beyond, we continued the morning session with a lecture on socialist art by Tomáš Pospiszyl, Czech critic, curator and art historian. In 2018 JRP Editions published Pospiszyl’s monograph An Associative Art History: Comparative Studies of Neo-Avant-Gardes in a Bipolar World which aimed to locate East European postwar art in global history. Speaking at his home institution – Pospiszyl is a lecturer at the Academy of Fine Arts in Prague – he gave a most amiable overview of the tasks for the study of East European art during the socialist era.

The presentation started on a positive note: East European art history has enjoyed much success during the last 15 years, nearly every important artist has had a catalogue published (in English) about his/her oeuvre, private and public collections have shown great interest in this field. However, at times this has come with a cost of assimilating western concepts to East European art. By emphasising neo-avant-garde tendencies or the semi-official artistic culture of the so-called grey zone, art historians have left behind blind spots in recent art histories, especially in terms of the most common official visual culture of the socialist era. In other words, we don’t know much about socialist art.

In order to encourage his colleagues to pick up the topic, Pospiszyl proposed dozens of ‘tasks’ (e.g researching the creation of socialist reality by socialist artists, analysing institutional conditions, looking into the relationship between high and low/mass culture under socialism) and urged fellow researchers to share the knowledge. I presume that the majority of the audience welcomed Pospiszyl’s urge to study the official art of the socialist era, but it seems to me that most of the listeners were reluctant to agree with the strictly socio-economically defined concept of socialist art. As always, it’s recommended not to go from one extreme to another.

(Gregor Taul)

Milan Grygar Unplugged

By confrontations, on 5 November 2019

Finding time in his hectic schedule, the chief curator of Modern and Contemporary Art Michal Novotný opened up the National Gallery for the Confrontations group on a Monday evening and gave us a wide-ranging talk in the cavernous space of the Milan Grygar retrospective. Born in 1926, with an enduring interest in contemporary music and its transposition into musical notation, Grygar’s spatial scores appear on canvas, as sculptural installations and as video works. The curator fielded searching questions from the participants on a variety of pressing topics, such as the ideal age for an artist to have a solo show in the National Gallery and the challenges of mounting shows in the enormous spaces of the Trade Fair Palace. He also shared with us the backstory of his Re-Orient series of exhibitions about East European artistic identity, the fourth instalment of which we were to see in Bratislava.

(MRF)

Czech Art Differently

By confrontations, on 5 November 2019

Giving insights into the history of the Confrontations exhibitions in Prague from the years around 1960 and the early 1980s, Pavlína Morganová began the group seminars at the Academy of Fine Arts. Among the specificities of the secluded spirit of the early Confrontations that she revealed was the rule that each artist was allowed to invite only a single visitor to the exhibition to avoid drawing the attention of the authorities, giving a fresh perspective on the question of audience numbers in exhibition making.

Giving insights into the history of the Confrontations exhibitions in Prague from the years around 1960 and the early 1980s, Pavlína Morganová began the group seminars at the Academy of Fine Arts. Among the specificities of the secluded spirit of the early Confrontations that she revealed was the rule that each artist was allowed to invite only a single visitor to the exhibition to avoid drawing the attention of the authorities, giving a fresh perspective on the question of audience numbers in exhibition making.

Hana Buddeus posed the question of what kind of art history could be reconstructed by taking account of the work of a photographer favoured by other artists to document their work through her research on prolific Czech photographer Josef Sudek. By analysing the content of these images, she demonstrated the fluidity in practice of divides between official and unofficial streams of artistic production.

Hana Buddeus posed the question of what kind of art history could be reconstructed by taking account of the work of a photographer favoured by other artists to document their work through her research on prolific Czech photographer Josef Sudek. By analysing the content of these images, she demonstrated the fluidity in practice of divides between official and unofficial streams of artistic production.

Johana Lomová drew attention to the specific role played by the applied arts in socialist states. To this end she focused on a lesser known aspect of the work of Czech art critic Jindřich Chalupecký, later renowned for his advocacy of neo-avant-garde and experimental art, but who during the 1950s and early 1960s published almost exclusively on the applied arts and their contribution to Czechoslovak socialist society.

Juliane Debeusscher put forward the idea of an Eastern-Southern European connection as a heterogeneous area of cultural transfers and entanglements during the Cold war. Examining the trajectories of Jiří Valoch’s exhibition exchanges with Franco’s Spain during the 1960s, she argued for a more differentiated understanding of ‘non-socialist countries’ rather than a monolithic West, in order to account for the cultural specificities of authoritarian dictatorships.

(Maja & Reuben Fowkes)

Hop Field Art

By confrontations, on 5 November 2019

Curator and art historian Marie Klimešová recounted to the group how her work progressed in the Czechoslovak art scene in the 1970s and 1980s, working outside official institutions and despite the challenges of the Normalisation period. She explained that her university courses at the Art Academy never went beyond Kandinsky and Brancusi for ideological reasons; nevertheless she was drawn to contemporary art and staged several exhibitions of “forbidden” artists (such as Jiří Sopko and Karel Nepraš), whose striking aesthetics, dark humor, and defiant spirit she admired.

Curator and art historian Marie Klimešová recounted to the group how her work progressed in the Czechoslovak art scene in the 1970s and 1980s, working outside official institutions and despite the challenges of the Normalisation period. She explained that her university courses at the Art Academy never went beyond Kandinsky and Brancusi for ideological reasons; nevertheless she was drawn to contemporary art and staged several exhibitions of “forbidden” artists (such as Jiří Sopko and Karel Nepraš), whose striking aesthetics, dark humor, and defiant spirit she admired.

One of her most impressive undertakings was a large-scale land art symposium held in 1983 at Chmelnice, in a hop field outside Prague and supported by the local Agriculture Cooperative. The artists, both Czechoslovak and from outside the country, included Magdalena Jetelová, Stanislav Zippe, Čestmír Kafka, Jitka Svobodová, Ivan Kafka, and Vladimir Merta. They made inventive use of the system of tall constructions made of 9 metre tall wooden poles that hop plants require in order to grow. The days long symposium created a sense of community among the artists, but unfortunately the works were destroyed almost immediately by the same members of the cooperative which hosted the participants on the demand of the authorities.

(Corina Apostol)

First Republic

By confrontations, on 5 November 2019

We had the opportunity to visit the exhibition 1918–1938: First Republic at the National Gallery in Prague in the company of co-curator Jitka Šosová. Through a vast number of artworks, this exhibition presents the artistic life of the interwar period, during the First Czechoslovak Republic. The curators have chosen to present the artistic production of this period concentrating on one aspect: the institutions. This well-defined approach makes the extensive material readable, creating a clear narrative of this period. The exhibition provides a refreshing, new look at interwar art in Czechoslovakia, offering new understandings, especially compared to traditional, stylistic narratives.

We had the opportunity to visit the exhibition 1918–1938: First Republic at the National Gallery in Prague in the company of co-curator Jitka Šosová. Through a vast number of artworks, this exhibition presents the artistic life of the interwar period, during the First Czechoslovak Republic. The curators have chosen to present the artistic production of this period concentrating on one aspect: the institutions. This well-defined approach makes the extensive material readable, creating a clear narrative of this period. The exhibition provides a refreshing, new look at interwar art in Czechoslovakia, offering new understandings, especially compared to traditional, stylistic narratives.

For me, the most interesting part however was not a specific institution but the introduction to the exhibition, featuring different charts: one showing the geographic setting with the numbered halls relating to the art centres, another highlighting the multi-national composition of the population, varying from region to region, and finally a chart providing a comparative periodization of the eighteen (!) institutions showcased at the exhibition.

The curatorial concept attempts to be as geographically inclusive as possible, dedicating one room to each major artistic centre, namely Brno, Bratislava, Zlín, Košice, and Užhorod. Nonetheless, thirteen parts are still dedicated to Prague. One, without a thorough knowledge of the different art scenes, only wonders whether this thirteen to five ratio in favour of Prague represents the overwhelmingly dominant role of the capital, or it is rather – at least partly – due to the composition of the collections at the National Gallery that the curators had to build upon? Whichever is case, the 1918–1938: First Republic remains a magnificent contribution to art history; one can only hope that the somewhat outdated floor dedicated to the post-war period will receive a similarly refreshing treatment in the close future.

The curatorial concept attempts to be as geographically inclusive as possible, dedicating one room to each major artistic centre, namely Brno, Bratislava, Zlín, Košice, and Užhorod. Nonetheless, thirteen parts are still dedicated to Prague. One, without a thorough knowledge of the different art scenes, only wonders whether this thirteen to five ratio in favour of Prague represents the overwhelmingly dominant role of the capital, or it is rather – at least partly – due to the composition of the collections at the National Gallery that the curators had to build upon? Whichever is case, the 1918–1938: First Republic remains a magnificent contribution to art history; one can only hope that the somewhat outdated floor dedicated to the post-war period will receive a similarly refreshing treatment in the close future.

(Daniel Véri)

Impermanent Collection

By confrontations, on 5 November 2019

After National Gallery’s permanent exhibition “1918-1938: First Czechoslovak Republic”, which gave a very good insight into the art produced in this time period including the representation of the wider cultural framework that influenced production, distribution and reception of the art, we visited the exhibition “1930-Present:Czech Modern Art“ with a gallery curator Adéla Janíčková. Intended to present progress and development of nation’s art— singling out important figures of the interwar avant-garde, the unofficial art of the 1950s, neo-avant garde, i.e., neo-constructivist tendencies, action art, new sensitivity to postmodernism — this permanent exhibition gave us a somewhat fragmented and homogenic view of a very complex history. There was a lack of narrative between official and unofficial art (also no Socialist Realism in the display) as well as the information on the socialist time or the social, cultural and political context that shaped these practices (in comparison to the First Czechoslovak Republic exhibition). In fact, this exhibition layout was indicative that the National gallery is in some kind of transition, suspended between past practices and future possibilities. For us, however, it successfully set the scene for the next event “Questioning National Collection”, the discussion dealing with issues on how to represent national identity as well as plurality and diversity of identity through its permanent displays.

(Asja Mandić)

Close

Close