The 1980s…And What Came After

By confrontations, on 28 August 2022

By Maja and Reuben Fowkes

The programme of the Confrontations meeting in London brought new perspectives to our ongoing discussions of the art of the 1980s in Eastern Europe, by offering a view of the last decade of socialism from outside the region. More specifically, presentations by Marysia Lewandowska and Fedja Klikovac revealed the complexities of artistic border crossings in an era that alternated between cultural and political stasis and epochal transformation.

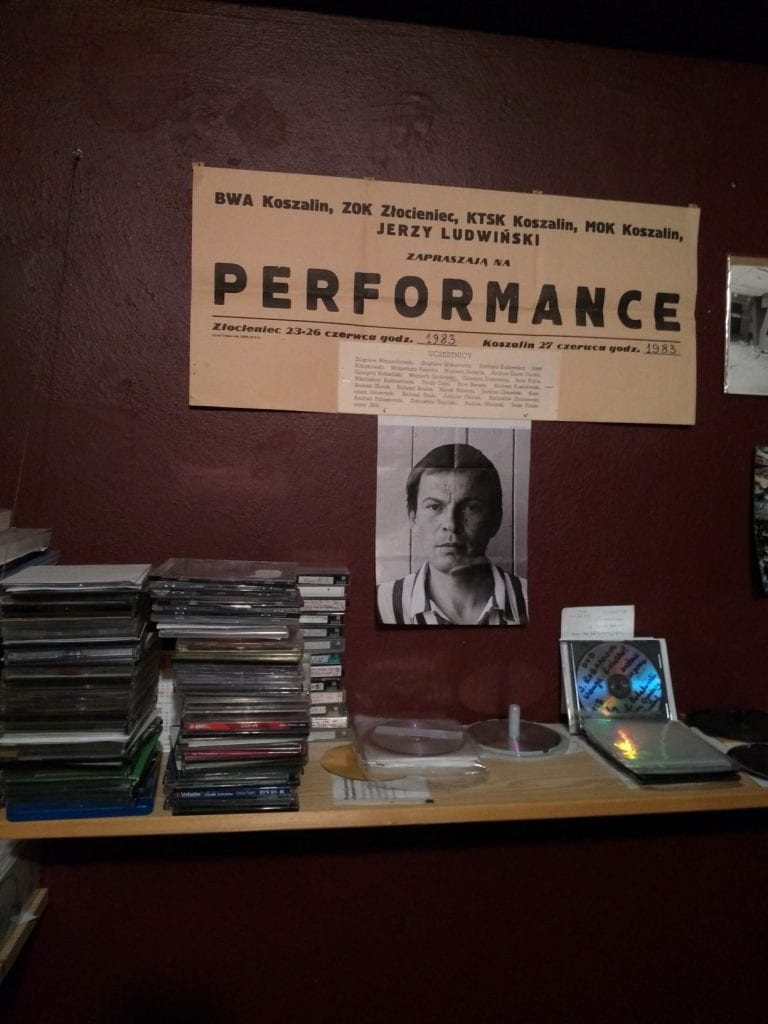

In her art practice, which across film, installation and interventions deals with the relation between public realms and private ownership in a variety of museum and archival settings, Marysia Lewandowska does not dwell on her own biography. We were therefore privileged that she took the opportunity of her presentation for the Confrontations group to talk about some of the less tangible connections between her personal history of emigration from Poland in 1984, taking a three day trip on an ocean liner in the company of fellow citizens fleeing the repressions of martial law, and the evolution of her artistic interests since settling in the UK. The group was in listening mode as she recounted the origins of the Women’s Audio Archive, a project that she launched in 2009 based on recordings of encounters in the artworld and academia taped during the 1980s. The archive is a record of the language and cultural specificities of the western artworld during a decade that saw the dissolution of the certainties of the Cold War era, but also the emergence of alternative positions and perspectives reflecting different histories and identities. Lewandowska’s abiding interest in the public realm, and the defence of public knowledge against privatising tendencies, come to the fore in her efforts to make the Women’s Audio Archive completely accessible and free of copyright restrictions. It is in the call to keep knowledge, culture and art free from state and market control that the autonomy-loving stream of Polish and East European neo-avant-garde thinking resurfaces in a different space and time, while the practices of self-instituting and self-archiving could also be traced to the art history of the region.

In her art practice, which across film, installation and interventions deals with the relation between public realms and private ownership in a variety of museum and archival settings, Marysia Lewandowska does not dwell on her own biography. We were therefore privileged that she took the opportunity of her presentation for the Confrontations group to talk about some of the less tangible connections between her personal history of emigration from Poland in 1984, taking a three day trip on an ocean liner in the company of fellow citizens fleeing the repressions of martial law, and the evolution of her artistic interests since settling in the UK. The group was in listening mode as she recounted the origins of the Women’s Audio Archive, a project that she launched in 2009 based on recordings of encounters in the artworld and academia taped during the 1980s. The archive is a record of the language and cultural specificities of the western artworld during a decade that saw the dissolution of the certainties of the Cold War era, but also the emergence of alternative positions and perspectives reflecting different histories and identities. Lewandowska’s abiding interest in the public realm, and the defence of public knowledge against privatising tendencies, come to the fore in her efforts to make the Women’s Audio Archive completely accessible and free of copyright restrictions. It is in the call to keep knowledge, culture and art free from state and market control that the autonomy-loving stream of Polish and East European neo-avant-garde thinking resurfaces in a different space and time, while the practices of self-instituting and self-archiving could also be traced to the art history of the region.

East European practices of self-instituting could also be a relevant point of reference for the career of Fedja Klikovac, who hosted the group in Handel Street Projects, a gallery which used to inhabit temporary spaces around London, but now has a permanent home on a residential street in Islington. He shared with us the prehistory of his curatorial and gallery activities, leading back to the time he spent as a participant in the distinctive ecosystem of the Yugoslav artworld in the 1980s. Born in Podgorica, the capital of Montenegro that at the time was known as Titograd, he studied art history in Belgrade in the late 1970s and was part of the vibrant international and alternative art scene around the Student Cultural Centre (SKC). His artistic career, which saw him exhibit in pivotal exhibitions such as Yugoslav Documents in Sarajevo in 1989, came to an end when he emigrated to London in 1992 following the outbreak of war. Actually it would be more accurate to say that his creativity took new directions, such as running the medievalmodern gallery in Marylebone in the early 2000s, based on the concept of inviting artists to make work in dialogue with medieval artefacts.

East European practices of self-instituting could also be a relevant point of reference for the career of Fedja Klikovac, who hosted the group in Handel Street Projects, a gallery which used to inhabit temporary spaces around London, but now has a permanent home on a residential street in Islington. He shared with us the prehistory of his curatorial and gallery activities, leading back to the time he spent as a participant in the distinctive ecosystem of the Yugoslav artworld in the 1980s. Born in Podgorica, the capital of Montenegro that at the time was known as Titograd, he studied art history in Belgrade in the late 1970s and was part of the vibrant international and alternative art scene around the Student Cultural Centre (SKC). His artistic career, which saw him exhibit in pivotal exhibitions such as Yugoslav Documents in Sarajevo in 1989, came to an end when he emigrated to London in 1992 following the outbreak of war. Actually it would be more accurate to say that his creativity took new directions, such as running the medievalmodern gallery in Marylebone in the early 2000s, based on the concept of inviting artists to make work in dialogue with medieval artefacts.

Also on view in Handel Street Projects was a display of works by Olga Jevrić, the renowned Yugoslav sculptor, whose first solo presentation in the UK was organised by Klikovac in 2019. The Confrontations group had seen Jevrić’s work in the Museum of Contemporary Art in Zagreb, and the artist’s singular sculptural oeuvre, above all her abstract works from the mid-1950s that fused metal and concrete into irregular forms, is also now represented in the collection of Tate Modern. This is indicative of the expansion of institutional collecting to encompass a greater range of periods and movements in East European art history, looking beyond the golden age of the neo-avant-garde in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

Also on view in Handel Street Projects was a display of works by Olga Jevrić, the renowned Yugoslav sculptor, whose first solo presentation in the UK was organised by Klikovac in 2019. The Confrontations group had seen Jevrić’s work in the Museum of Contemporary Art in Zagreb, and the artist’s singular sculptural oeuvre, above all her abstract works from the mid-1950s that fused metal and concrete into irregular forms, is also now represented in the collection of Tate Modern. This is indicative of the expansion of institutional collecting to encompass a greater range of periods and movements in East European art history, looking beyond the golden age of the neo-avant-garde in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

Both Klikovac and Lewandowska’s presentations made vivid the presence and often still invisible influence of East European art history on the institutions and practices of the British artworld and academia, while suggesting fleeting parallels between the economic geographies of the UK and Eastern Europe, which during the 1980s underwent different but related versions of de-socialisation and re-marketisation.

Close

Close