By Blog Editor, on 7 December 2022

Education and skills contribute to differences in earnings and opportunities across generations, both at the national level and between local authorities in England. Targeted policies can help to reduce the gaps between individuals and contribute to efforts to level up the UK economy.

The UK is very unequal, in terms of both outcomes and opportunities. Among developed nations, it has one of the highest rates of income inequality – unequal outcomes – and one of the lowest rates of intergenerational mobility (unequal opportunities).

This is illustrated in the Great Gatsby Curve, a coinage of the late, great economist and US presidential adviser Alan Krueger, based on work by Miles Corak, which highlights how greater inequality is associated with less mobility across generations (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: The Great Gatsby curve

Based on this evidence, for the past few decades, successive governments have been focused on improving social mobility, equalising opportunities or, more recently, levelling up. But these things are notoriously hard to measure, not least because policies enacted today can take decades to come to fruition in terms of future changes in inequality.

Research looking at human capital emphasises the importance of education and skills in driving productivity, wages and economic growth. Those that invest in education and training are more likely to have higher skill levels and be more productive, which means that they can earn higher wages.

Education and skills have also been shown to play a direct role in inequality, contributing to differences in earnings and opportunities across generations, both at the national level and across local authorities in England.

Studies show that differences in skills can explain at least a third of the variation in earnings within countries. Further, education and skills can account for 60-80% of the transmission of income across generations – or unequal opportunities.

Trends in inequalities in education and skills can therefore give us some useful insight into future patterns of social mobility. For example, given the improvements in the educational performance of pupils in London seen over the last two decades, it is little surprise that the capital now appears to be one of the most mobile areas in the country in terms of labour market outcomes.

What do recent trends in educational inequalities tell us about progress with levelling up?

The recent evidence on levelling up doesn’t look good. Trends in educational attainment across regions show that educational inequalities are widening across places. London continued to pull away from other regions across primary school, GCSE and A-levelachievement in 2022 compared with 2019, before the Covid-19 pandemic.

While attainment fell everywhere due to the impact of the pandemic and learning losses, key stage 2 results fell by six percentage points (ppts) in London compared with eight in the North West. Similarly, 65% of London pupils achieved the expected standard in reading, writing and maths in 2022, compared with 57% in the North West, and 56% in Yorkshire and Humber, and the East (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Map of England by key stage 2 attainment

Source: Department for Education, 2022

At key stage 4, 32.6% of GCSE entries were awarded grade seven or above in London in 2022. In the North East, the figure was 22.4%, a difference of 10.2 ppts. In 2019, the corresponding gap was 9.3 ppts.

Similarly, at A-level, the percentage of pupils achieving an A grade was 39% in London, compared with 30.8% in the North East, a gap of 8.2 ppts in 2022, relative to 3.9 ppts in 2019.

There are two points to make about this. First, the fact that attainment fell everywhere is really bad news for future productivity. If pupils are progressing with less knowledge than they had previously, they have fewer of the building blocks needed for their next stages of learning – a less solid foundation to build on moving forward. This could have very serious consequences for future labour market productivity – estimates on the cost of this ‘learning loss’ range from billions to trillions of pounds. Second, the widening of these gaps is the opposite of what we want to be seeing if we are to level up or minimise the differences between regions of the UK. These widening educational inequalities are likely to translate, in part, into widening labour market earnings and incomes unless action is taken to address the disparities.

Is there scope for this to improve?

The government has committed to a range of policiesto level up the economy, including 55 new educational investment areas (EIAs), provision of high-quality online curriculum through Oak National Academy and setting the target of 90% of primary school children achieving expected standards in reading, writing and maths by 2030. There is also talk of an overhaul of funding and governance in colleges, a skills audit, and local skill improvement plans to target specific regional needs.

Yet looking forward, it is hard to see how this picture will improve against a backdrop of increasingly squeezed school budgets. Even before the pandemic, work by the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) showed that the gap in funding between state and private schools has grown steadily since 2010 (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: State school spending per pupil vs average private school fees over time (2021–22 prices)

Indeed, spending per pupil in state schools declined by 9% in real terms between 2019 and 2020. This has disproportionately hit schools serving more deprived pupils and further education colleges.

Alongside the pressure of learning losses from the pandemic, the cost of living crisis and rising teachers’ wages to be paid out of existing budgets, it is hard to see how the education sector will be able to offer the support needed, particularly for the most deprived pupils.

Where can I find out more?

This post first appeared on Economics Observatory on 7 December 2022.

By Blog Editor, on 5 December 2022

By Jake Anders

Covid-19 caused significant and widespread disruption to young people’s education. But the effects were not the same for everyone. Many pre-existing inequalities have been exacerbated, including those between state schools and independent schools.

The pandemic has had a major effect on the education and wider lives of children and young people, ranging from access to early years provision, learning losses among school age pupils, and broader effects on mental health and wellbeing (Farmer, 2020). But the impact has not been the same for everyone.

It has become clear that school closures and online learning due to the pandemic have exacerbated existing inequalities in education. Those from disadvantaged backgrounds and pupils with additional needs (including special educational needs and disabilities) have been especially badly affected by the disruption. In this article, we focus particularly on inequalities that emerged through differences in the responses of state and private schools.

Less than 10% of young people in England attend a private school during their education. Nevertheless, these institutions have an outsized influence on the persistence of educational advantage. They are highly socially selective, with the vast majority of those attending private schools coming from families in the top 10% of the income distribution (Anders et al., 2020; Henseke et al., 2021).

Further, the gap in resources between state and private schools is large (Green et al, 2017). It has grown larger over the past decade: from £3,100 per pupil per year in 2010/11 to £6,500 by 2020/21 (Sibieta, 2021).

Based on a combination of these factors, people who have attended private schools are disproportionately likely to be employed in high-status jobs later in life (Sullivan et al., 2016). Privately educated graduates are a third more likely to enter a high-status occupation than state-educated peers from similar families and neighbourhoods (Macmillan et al., 2015).

Early on in the pandemic, there were many anecdotes about differences in school responses, emphasising some schools’ rapid move to live online lessons. But much of the data available to test these narratives only covered state schools (a notable exception is Andrew et al., 2020).

Things have changed with new data from the COVID Social Mobility & Opportunities study (COSMO). This cohort study of young people in Year 10 at the pandemic’s onset provides high quality new data to explore the issue. Here, we consider some of the differences that emerged between state and private schools due to the large resource differences and why they matter.

Schooling in lockdown

When the first national lockdown began in the spring of 2020, schools played a vital role in responding to myriad challenges facing their pupils. With concerns about welfare and wellbeing, it was understandable that tasks such as free school meal voucher distribution, checking on how pupils’ families were coping in terms of mental health, welfare and food, and providing information on where they could obtain support distracted from efforts to organise online learning for pupils. This was particularly acute for schools with many pupils from disadvantaged backgrounds (Moss et al., 2020).

With more resources and fewer issues to solve, private schools were able to move quickly to set up alternatives to in-person classes. For example, 94% of private school participants who responded to the COSMO study received live online lessons during the first national lockdown.

This was 30 percentage points higher than the rate reported among those in comprehensive schools. The vast majority (84%) also reported receiving more than three online classes per school day during this period, compared with 41% in state grammar schools and 33% in state comprehensive schools.

Figure 1: Provision of live online lessons, by school characteristics, lockdown one (March-June 2020) and lockdown three (January-March 2021)

Source: COVID Social Mobility & Opportunities study (COSMO).

Notes: N=12,505, including 11,317 in state comprehensive group; analysis weighted to account for study design and young person non-response.

There were not national school closures during the second lockdown (in the autumn of 2020). By the third national lockdown in early 2021, state schools with the most advantaged intakes had largely caught up with private schools’ remote learning provision.

Pupils in these schools were now similarly likely to be offered remote lessons (around 95% in state grammar and state comprehensive schools with the least disadvantaged intakes). But they were still not providing as many per day, with 82% of those in state grammars and 71% in the least deprived state comprehensives reporting receiving more than three online classes per day, compared with 93% in private schools.

On the other hand, state schools with more disadvantaged intakes had made less progress on both fronts – 80% of pupils in these schools reported receiving any online lessons and 53% more than three per day – remaining behind in terms of online lesson provision.

Pupils at independent schools were also more likely to have regular contact with a teacher outside class during lockdowns. Here, state schools caught up slightly in the third lockdown.

But state comprehensive pupils were more than twice as likely to report difficulties in accessing support from teachers than pupils at private schools (17% compared with 8% in the third lockdown).

Pupils at private schools also reported spending more time on schoolwork during lockdowns than their state school peers. This added up to more than one extra working day per week of time spent on schoolwork in both the first and third lockdowns.

Many of these differences are not down to the schools directly. Rather, they are due to challenges faced depending on pupils’ circumstances.

For example, almost a quarter of pupils attending state comprehensives with the most deprived intakes did not have access to a suitable device for joining remote classes in the first lockdown. This figure was under 2% for pupils at independent schools.

Similarly, 13% of those at state comprehensive schools reported issues due to having to share devices needed to take part in online learning. Only 4% at independent schools faced the same issue.

Catch up

Given these inequalities, it is unsurprising that young people at state schools were more likely to think that their progress has suffered because of the Covid-19 disruption. In state schools, 81% of pupils reported this, compared with 72% at private schools. To address this, a much larger effort to support young people in state schools to catch up is needed.

This is especially important as the gap in disruption to learning did not stop with the resumption of in-person schooling. For example, teacher absence has taken a larger toll on state schools in the post-restrictions period of the pandemic.

Staff absence rates due to Covid-19 infections in state schools have been higher than private schools. In a snapshot survey in early 2022, 20% of state school teachers reported that at least one in ten staff in their school were absent. Only 12% of private school staff reported the same (Sutton Trust, 2022).

What have we learned about differences in catch-up activities between state and private schools? Evidence from the COSMO study finds that 53% of young people took part in at least one type of catch-up activity.

This figure was 54% for young people in state comprehensive schools, and slightly lower at 51% for those in independent schools. So, there is some evidence of differential catch up weighted towards the state sector, but it is not large. The definition of catch-up activities is wide, from extra online classes to one-to-one tuition. The latter of these is most likely to have had significant catch-up benefits (Burgess, 2020).

Focusing on the offer of tutoring, this was more likely for young people at independent schools (52% compared with 41% in state comprehensive schools). This is despite the government’s flagship National Tutoring Programme (NTP).

The NTP was meant to target this sort of provision to pupils who needed it most. Unfortunately, its reach was narrower than hoped, with an official evaluation report highlighting that ‘only around a half of school leads and staff felt that all or most of the pupils selected were disadvantaged’ (Lord et al., 2022).

That said, pupils in independent schools were less likely to have taken part in tutoring than those in state schools. Among independent school pupils, 23% said they had taken up this offer, compared with 27% in comprehensive schools. This seems to reflect pupils in private schools being less likely to feel that they needed this help, even if it was being offered. An equally important aspect of pupils’ ability to re-engage fully in their education is their mental health. Pupils attending private schools were more than twice as likely to report that their school mental health support was very good (26%) than state school pupils (10%) (Holt-White et al., 2022)

Figure 2: Whether participant agreed they had caught up with lost learning during the pandemic, by gender and school type

Source: COSMO Notes: N=12,149; analysis is weighted for survey design and young person non-response.

Despite catch-up efforts, pupils at state comprehensive schools were the least likely to think they had been able to catch up (34%). This compared with 58% of pupils at independent schools who felt this way. Almost half (46%) of pupils at comprehensive schools said they had not been able to catch up, while just over a quarter (27%) at independent schools felt the same.

Assessment during Covid-19

Because of the disruption to schooling, the government decided to replace GCSE and A-level exams with teacher assessed grades in 2020 (and centre assessed grades in 2021). Some adaptation was unavoidable, given the Covid-19 restrictions. But many highlighted the importance of retaining externally set and marked assessment (Anders et al., 2021).

Indeed, there is evidence of biases in teacher assessed grades that affect ethnic minority groups, those from lower income backgrounds, boys and those with special educational needs (Burgess and Greaves, 2013; Campbell, 2015). Top grades awarded in the two years in which teacher or centre assessed grades were used jumped up compared with the years before.

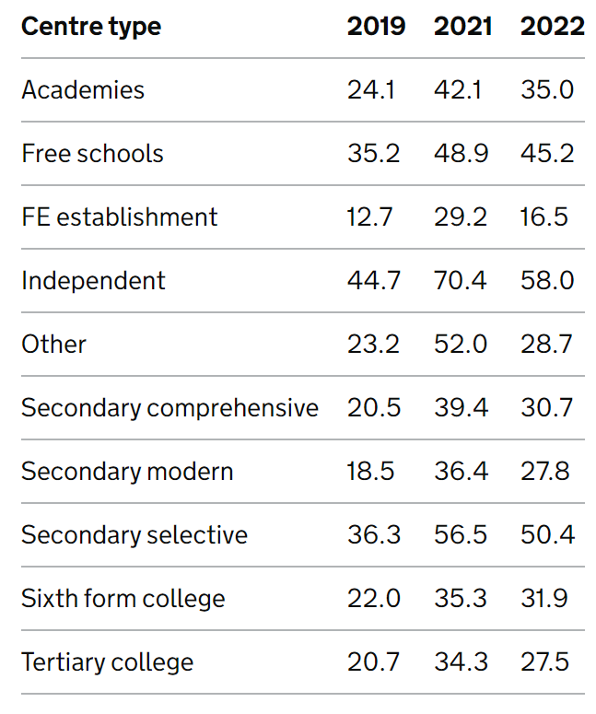

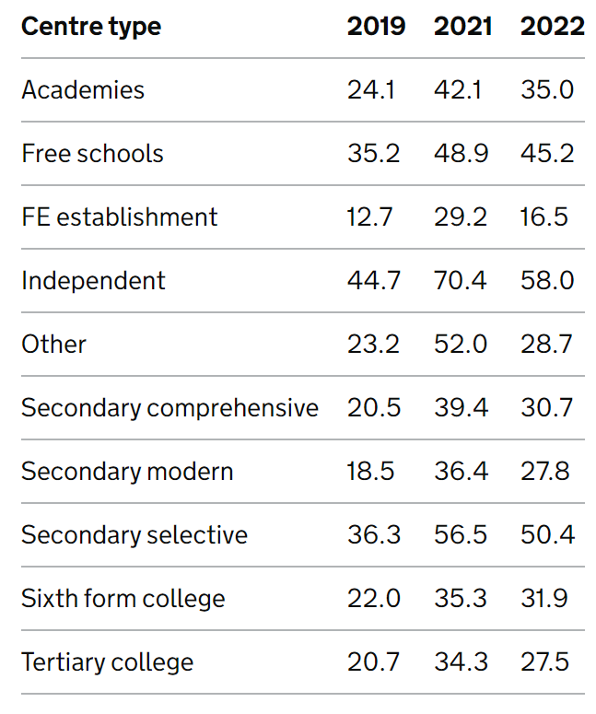

But the increase was most prevalent in private schools (Anders and Macmillan, 2022). The proportion of A grades awarded at A-level rose from 44.7% in 2019 to 70.4% in private schools in 2021 (compared with a rise from 24.1% to 42.1% in state academy schools).

Some of this could have been due to the differences in provision highlighted above. Yet, the particularly dramatic fall in grades for private schools in 2022 – a cohort that had more of their education disrupted – casts doubt on this.

We can also use findings from the COSMO study to understand differences in assessment practices between the sectors. Pupils in this cohort received teacher assessed grades for their GCSEs in 2021.

Private school pupils were more likely to say that their teacher assessed grades were better than expected than state school pupils. Likewise, they were much less likely to report that they did worse than expected. As with the changes in grades over time, this suggests a more generous approach to teacher assessed grades in private schools.

Whatever the exact mechanisms, these results represent a significant widening of the qualifications gap between state and private school pupils. This will have had – and will continue to have – significant implications for pupils’ future educational and employment trajectories.

Conclusion

Taken together, we can see that there are a range of ways in which disruption as a result of the pandemic has laid the groundwork for increased inequalities between pupils who attended state and private schools throughout their lives.

Existing gaps have been reinforced by differences in schools’ capacity to implement quick and effective responses at the outbreak of the pandemic.

It seems unlikely that these inequalities have been fully addressed with the fairly small differences in catch-up offerings – pupils themselves reinforce this view. And the use of teacher assessment in the place of usual exams appears to have baked in the results.

We will not know the full extent of the implications of this disruption for years to come. The COSMO study is designed to try to help us to do exactly that.

Some of the differences may unwind. For example, if some pupils’ grades were flattered more by teacher assessment than others, we would not expect this in itself to result in long-term productivity gains and hence to affect individuals’ wages (Wyness et al., 2021). Nevertheless, the knock-on effects (for example, access to university) may still reinforce the educational gap.

Ultimately, the early signs are not promising for inequalities in life chances between state and privately educated pupils as a result of the pandemic. We must not forget about the young people who have been disproportionately affected during this time.

As the pandemic subsides, it is easy to focus on ‘getting back to normal’, but in reality, extraordinary efforts are still needed to try to address these inequalities.

While important in itself, ensuring everyone is given the opportunity to achieve their potential in life is vital to the country’s productivity and, hence, everyone’s future economic prosperity.

This article was first published on the Economics Observatory on 5 December 2022.

By Blog Editor, on 1 December 2022

By Asma Benhenda

Shortages of school teachers – caused by a long-term decline in the competitiveness of their pay as well as challenging working conditions – are a global concern. Effective policy interventions could include targeted pay supplements and encouraging more supportive leadership practices in education.

Teacher shortages are one of the main challenges faced by education systems in most developed countries, including the UK. They stem from a combination of recruitment and retention issues. Specifically, there are not enough teaching candidates and many trained teachers leave the profession.

Policy-makers can increase the attractiveness of the profession by addressing the root causes of staff shortages: low pay and challenging working conditions. These factors are even more critical today, particularly in the context of high inflation rates and pandemic-induced learning losses among school-age children.

How does England compare to other countries?

Teacher shortage is a major issue affecting many developed countries. On average, more than a quarter of pupils across OECD countries are enrolled in schools whose leaders have reported that learning is hindered by a lack of teaching staff. In England, this figure is slightly above the OECD average, at 28.1% (OECD, 2018a).

The lack of teachers is also affecting ratios of staff to pupils. In England, pupil numbers in 2019 were more or less the same as in 2007, but teacher numbers had fallen by 7%, according to the Education Policy Institute (EPI).

This trend has emerged as a result of difficulties in both recruiting and retaining teachers. First, there are not enough teaching candidates. In England, the government regularly misses its recruitment targets, especially at secondary school level, and in sciences and languages.

Subjects that did not meet recruitment targets in 2020/21 included physics (only 45% of the target was reached), modern foreign languages (72%), design and technology (75%), chemistry (80%) and maths (84%) (Department for Education, DfE, 2022).

Second, many teachers are leaving the profession. England also suffers from high teacher attrition rates: 22% of teachers aged 50 or younger want to leave teaching within the next five years. This is above the OECD average of 15% (OECD, 2018a).

Teacher attrition in England is getting worse over time. Nearly three-quarters (74%) of teachers who qualified in 2010 were still teaching four years later. This has declined to about 70% among those who qualified in 2014.

Further, teachers are also much more likely to leave the profession in their first few years of teaching. According to the EPI, a fifth of teachers exit after their first two years, while 40% leave after five years (EPI, 2020).

Teacher attrition and turnover are particularly problematic in schools in more disadvantaged areas, which have a harder time both recruiting and retaining teachers. In England, 22% of schools in the most affluent areas report vacancies or temporarily filled positions. This increases to around 29% of schools in the most disadvantaged areas outside London and 46% in the most disadvantaged areas within London (EPI, 2020).

Similarly, the share of experienced teachers is seven percentage points lower in socio-economically disadvantaged schools than in advantaged schools. This gap is more than twice the OECD average (OECD, 2018b). The unequal exposure to experienced teaching staff contributes further to persistent educational inequalities (Gershenson, 2021).

How has Covid-19 affected teacher shortages?

Teacher applications in the UK increased temporarily during the pandemic. Compared with 2019, postgraduate initial teacher training applications were 17% higher in 2020 and 11% higher in 2021.

This allowed the DfE to reach its recruitment target in secondary schools for the first time since 2011/12, although recruitment targets were still missed in maths and sciences (National Foundation for Educational Research, NFER, 2022).

As a largely public sector job, teaching was relatively sheltered from the economic shock of the pandemic and therefore temporarily more attractive (Benhenda, 2020).

But the pandemic boost in teacher recruitment was short-lived and is unlikely to compensate for years of under-recruitment (House of Commons, 2021). Indeed, teacher recruitment is now below pre-pandemic levels, as the wider labour market rebounds.

Teacher applications are expected to be 15% lower in 2022 than in 2019 (Worth, 2022). This trend is likely to persist. Teachers are experiencing, on average, real terms salary cuts of 5% as the government’s proposals for teacher pay in 2022 and 2023 are likely to deliver salary rises well below expected inflation (Sibieta, 2022).

Even more worrying are the early signs of a post-pandemic rise in teacher attrition. Teachers’ intentions to leave the profession have increased because they feel that their working conditions have deteriorated considerably (EPI, 2021).

We do not have conclusive data on this trend in England yet, but evidence from the United States shows a 20% increase in attrition rates post-pandemic (Goldhaber and Theobald, 2022).

What policies might be effective at reducing teacher shortages?

Teacher shortages will remain a major policy challenge while the root causes – the long-run decline in pay competitiveness and difficult working conditions – are not properly addressed (Garcia and Weiss, 2020).

Teacher pay

Teachers are paid less than their non-teacher university-educated counterparts. They face this pay penalty in most developed countries.

For example, in the United States, the average weekly wages of teachers are 32.9% lower than those of other college graduates. After adjusting for age, formal education level, marital status, race/ethnicity and state of residence, the teacher wage penalty is estimated to be 23.5%. This has been on a worsening trajectory since the mid-1990s when it was only 6.1% (Allegretto, 2022).

In England, the teacher pay penalty is lower but still significant. Teachers in England are paid, on average, around 10% lower than the average tertiary (university or college) educated worker (OECD, 2021).

These averages hide large differences by teaching subject. Most of the teacher wage penalty is borne by maths and science graduates as some non-science graduates – such as art graduates – benefit from a pay premium when they choose a career in teaching (Allen et al, 2018).

This is correlated with higher attrition rates among maths and science teachers. The odds of newly qualified teachers leaving the profession are 20% higher for science teachers than for non-science teachers (Allen and Sims, 2017).

The government has put in place teacher retention payments for maths and physics teachers to address this issue. In 2019 and 2020, early-career maths and physics teachers in disadvantaged areas in England received an 8% wage bonus.

Research shows that eligible teachers are 23% less likely to leave teaching in state-funded schools in years when they were eligible for this payment. A 1% increase in teacher pay reduces the risk of them leaving the profession by 3% (what is known as a pay elasticity of exit of -3).

This is similar to results from evaluations of comparable policies in the United States. It suggests that persistent shortages of maths and science teachers can be reduced through targeted pay supplement policies (Sims and Benhenda, 2022).

Teachers’ working conditions

Teachers in England report one of the lowest levels of job satisfaction among OECD countries. These levels have been declining over time. For example, in 2018, fewer lower-secondary teachers in England believed that the advantages of being a teacher outweigh the disadvantages compared with five years previously: 83% versus 72%, respectively.

Similarly, the proportion reporting that they would still choose to work as a teacher if they were to make their career choice again is also declining (80% in 2013 versus 69% in 2018) (Jerrim, 2019).

Figure 1: Changes in job satisfaction among lower-secondary school teachers in England

Source: Jerrim, 2019

Note: Bars refer to the percentage of teachers who agree or strongly agree with each statement.

Job satisfaction among teachers hit a new low during the pandemic because of increasingly challenging working conditions (DfE, 2022). These were partly due to the impact of school closures on pupils’ learning and development, especially in disadvantaged schools (Blanden et al, 2021).

Evidence on the effects of these non-financial dimensions of teaching on retention is less developed than evidence on financial incentives.

Nevertheless, research suggests that one important influence on teachers’ decisions to leave the profession is the quality of working conditions in their school. More specifically, supportive leadership is one of the factors that is most strongly associated with teacher retention (Sims and Jerrim, 2020).

Teachers identify the quality of administrative support as a key factor in decisions to leave a school. In addition, they point to the importance of school culture and collegial relationships, time for collaboration and decision-making input. These are all areas in which head-teachers play a central role (Trickle et al, 2011).

More evidence is needed on what makes a good head-teacher and how to improve head-teacher quality, as well as selection and training policies. Further research is also needed on retention policies as England suffers from a long-term trend of head-teachers leaving the profession because of the pressures of their job (Zuccollo, 2022).

Conclusion

Low pay and challenging working conditions are the root causes of teacher shortages in England, as well as in many other developed countries. The pandemic and lack of public investment in education have exacerbated this problem over the last few years.

Recent evidence shows that persistent shortages can be reduced through targeted pay supplement policies, as teacher retention is very sensitive to pay. Supportive leadership is another factor strongly associated with teacher retention. More evidence is needed on what makes a good head-teacher and how to improve head-teacher quality, as well as selection and training policies.

This article was first published on the Economics Observatory on 30 November 2022.

By Blog Editor, on 13 October 2022

Jake Anders is the Principal Investigator of the COVID Social Mobility & Opportunities study (COSMO), and Associate Professor and Deputy Director of the UCL Centre for Education Policy & Equalising Opportunities (CEPEO)

Today marks an important landmark in the COVID Social Mobility & Opportunities study (COSMO) and, with it, our understanding of the unequal impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on young people’s life chances. After more than 18 months of development and fieldwork, we are releasing initial findings and data from the first wave of this planned cohort study.

Unlike much other research from the pandemic, COSMO comes as close as possible to recruiting a representative group of young people from across the country. This is because it is based on invitations to a random sample of all young people in schools across England, rather than a convenient sample collected for some other purpose who are not, therefore, necessarily similar to the population of young people as a whole. Why does this matter? Having a representative sample gives us increased confidence that our findings paint an accurate picture of the extent and variation in the experiences of this group.

As a result, we are extremely grateful to the more than 13,000 young people across England who responded to our invitation to take part in this study, providing us with details of their experiences to help us build up a picture of the lives of this generation and how it has been disrupted. Through this, COSMO is providing vital new evidence on the effects of the pandemic on the lives of young people, with strong signs that it has severely widened existing educational inequalities: 80% of participants told us their academic progress suffered because of the pandemic’s disruption — a figure that is even higher among those from less advantaged backgrounds. Moreover, there are worrying signs that initial impacts have not been fully addressed by the policy response in this country: only about a third of young people told us they have been able to catch up with their lost learning.

Participants’ views on whether their academic progress has suffered

We are documenting aspects of young people’s experiences during and beyond the pandemic in a series of briefing notes authored by members of the COSMO research team, with the first three of these on ‘lockdown learning’, ‘education recovery and catch up’, and ‘future plans and aspirations’ released today and more to come. These shine a light on important details of young people’s experiences.

Changes to educational plans by COVID-19 status

They highlight, for example, that well over half of young people report some change to their education and career plans because of the pandemic, and that this is particularly the case among those who report more acute direct experiences of COVID-19 itself, raising important questions about the consequences of such shifts if they are realised in the years to come.

They also increase our understanding of barriers to learning in lockdown, helping us to break down the factors that seemed to limit home learning, notably the lack of suitable electronic devices to engage in remote lessons or other online educational activities — this is particularly concerning given that over half of those who lacked such a suitable device told us this need had still not been met at the end of the second period of national school closures.

The extremely rich data from COSMO covering the circumstances and experiences of this representative sample of young people, are now available for other researchers to use to address other vital research questions. COSMO is not just a standalone effort to set out the findings as we see them, but also a resource to support others carrying out research to understand this generation.

But, importantly, COSMO’s ability to tell us about these short-term effects is just the start. COSMO is designed as a cohort study, which means that we aim to continue following the lives of its members over the coming years. Just as we are publishing findings from our first survey, we are just getting started in the process of inviting members of the cohort to take part in the first follow-up. Establishing this link through time will be vital to understanding whether conditions during the pandemic have lasting consequences for decisions that young people make about their wellbeing, education, careers and more. Cohort studies for previous generations, such as the British Cohort Study that continues to follow a group of people born in 1970, have been vital to illuminating our understanding of social mobility in society – extending such understanding to the current generation with their unique experiences completing their education will only become more vital.

Whether or not we think of the pandemic as over, its effects will continue to cast a long shadow, and COSMO will continue to help us to understand this in the years to come.

By Blog Editor, on 18 August 2022

Jake Anders and Lindsey Macmillan

This year sees A-level (or equivalent) results for the cohort of pupils who were on the cusp of sitting their GCSEs in 2020 when exams were first cancelled due to the Covid-19 pandemic. Now exams are back, much to the dismay of many who believe that teacher-assessed grades should become the new norm. Here at CEPEO, we’ve regularly made the case for externally set and externally marked exams, based on academic evidence that teacher assessment leads to biases against certain groups. But what has the return of exams meant for results?

The implementation of a “glide path” has been successful – generally speaking, the results are pretty much halfway between those from 2019 and 2021. While the headlines are all focused on grades being down on last year, they are, if anything, slightly more generous than might have been predicted given the intention to deal with half of the grade inflation from teacher assessment seen in 2020 and 2021. This will be driven by the fact that these weren’t strictly exams in the 2019 sense – leniency in marking was encouraged and pupils had extra information in advance of exams, which may also have had other consequences that we’ll come back to shortly.

They don’t mean that learning loss for these students is no longer a problem – since the overall level of grades was decided by that “glide path”. As such, we do not know if this group of students would have achieved as good grades as their peers in 2019 despite the disruption. This is particularly the case given some remaining incomparability with 2019 around leniency in marking and advance notice of exam content. Ongoing concerns about learning loss, its consequences, and support for catching up need to be informed by other evidence, not allayed by these results.

Regional differences present a worrying picture for inequalities – the gap in the proportion of pupils achieving A or above at A level has increased between regions, from 7.3ppts in 2019 to 8.2ppts in 2022. So, London and the South East are continuing to pull away from other areas while the North East and Yorkshire and the Humber are particularly being left behind. This trend of Southern regions pulling ahead was also evident in the Key Stage 2 data released last month, and will provide a big headache for a government that has put ‘levelling up’ at the heart of what they plan to achieve.

Source: JCQ

A mixed picture across centre type – FE colleges and independent schools have seen the biggest absolute declines in the proportion of A-levels awarded A or above. For independent schools, this is not altogether surprising given their huge grade inflation from 2019 to 2021, which saw a massive 25.7ppt increase in the proportion of pupils achieving A or above over the period, and over 70% of all private school pupils awarded an A or above in 2021. This number has returned to a more ‘reasonable’ 58% for 2022. Two points to make here: First, this highlights the extent of grade inflation in this type of centre during the period of teacher assessment. Second, this is still an extremely high proportion of pupils achieving a grade A or above, which could be indicative of private school pupils being better placed to make use of the additional information on exam content made available in advance this year, as well as the advantages that private school pupils had in terms of relative learning loss during the pandemic.

FE colleges are far more puzzling – they have seen a similar absolute decline in the proportion achieving A or above, but from a much lower base. They saw a 16.5ppt rise in pupils achieving A or above from 2019 to 2021, only 29.2% reached this level of achievement by 2021. This has fallen back down to 16.5% in 2022. Somewhat speculatively, it seems plausible that students in FE colleges were, in contrast to those at independent schools, particularly badly affected by the disruption wrought by COVID-19.

Source: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/guide-to-as-and-a-level-results-in-england-summer-2022

Grammar schools, on the other hand, have found themselves performing at a level that is almost comparable with that seen in 2021, despite the different type of assessment, and 14.1ppts higher than 2019. One explanation for this could be, like private schools, that grammar school teachers and pupils were better placed to use the additional information released in advance of exams this year, focusing on a far narrower set of curricula. Additionally, this may be the first indication (through exam results at least) that pupils from more advantaged backgrounds were less constrained by learning loss during the pandemic.

In many ways, these results have not told us much we did not already know – it was already pretty clear that independent school grades, especially, were artificially inflated by teacher assessment, although the percentage coming back down now challenges those who told a tale of Covid learning loss advantages last year. We already knew that the impacts of COVID-19 disruption were likely to be unequal. And we already knew that this was going to be an extremely tough transition for those young people in the middle of it, rightly proud of what they have achieved through difficult circumstances, but unsure of what it all means compared to their peers one year above or below them.

By Blog Editor, on 25 May 2022

Arun Advani and Claire Crawford

Today marks the launch of the Department for Education’s new Unit for Future Skills (UFS). Its remit is to use existing data – and champion the creation of new data – to better understand the skills businesses want and whether the education and training system is delivering them.

A focus of the UFS is to improve understanding of ‘skills mismatches’ – the gaps between the demand for and supply of different skills. The idea is that by learning more about skills mismatches and, crucially, their sources, we can design more effective policies to close these gaps, and hence raise productivity.

The UFS was the brainchild of the current Secretary of State for Education, Nadhim Zahawi. Its origins, though, lie at least in part in the Skills and Productivity Board (SPB), set up by the former Secretary of State for Education, Gavin Williamson, to investigate both skills mismatches and how skills contribute to productivity. The SPB comes to an end as the UFS launches.

This apparent change in remit between the UFS and its predecessor is an important one. While the focus of the new unit on collating and sharing data is undoubtedly welcome, the loss of the explicit link to productivity risks losing the ‘bigger picture’ rationale for such a unit.

Part of our work on the SPB – on which we sat alongside four other academic experts – was to provide some initial insights into the skills which seemed to have significant mismatches between demand and supply, or for which demand was likely to grow over time.

Unfortunately, the data at our disposal were not well suited to identifying skills mismatches, and we made a series of recommendations to the Secretary of State about the ways in which the UFS could improve upon this. For example, information about the demand for skills is collected either using relatively small-scale national surveys or in different ways across different local areas, for example as part of the new Local Skills Information Plans, making granular information that is comparable across areas difficult to obtain. Instead, we had to infer the demand for skills by combining information on the number of jobs in different occupations in the economy with the importance of each skill in those occupations.

The difficulties in identifying the supply of skills were even greater: while the Longitudinal Education Outcomes (LEO) data provides excellent information about the qualifications of younger cohorts in England, there is no straightforward way of identifying which skills – rather than knowledge – different qualifications develop, and no way to reflect the skills that workers acquire – or indeed lose – through on-the-job training rather than in formal education.

Despite these challenges, our analysis highlighted some skills which seemed to be particularly important and potentially worthy of further investment by the government:

- We identified a set of ‘core transferable skills’ that are important across a large number of jobs in the economy now, and are expected to remain so in future. These skills included communication skills, people skills and ‘information skills’ – including decision-making, problem solving and critical thinking. Ensuring people have these skills means they should be equipped to perform a range of jobs well, and should also help them to transfer between jobs as needed.

- We also identified a set of skills that, despite being important for only a small number of jobs, seem to be in shortage now, and are valuable in occupations that contribute disproportionately to productivity. These include Science, Technology, Engineering and Maths (STEM) knowledge and the application of this knowledge, including scientific and mathematical reasoning.

The appropriate policy responses to these findings are not straightforward. While encouraging more people to study STEM subjects may be sensible for many reasons, it may not help fill STEM job vacancies: not if the main challenge is that these occupations pay a lot less – or have other less attractive job characteristics – than occupations in which those skills can be equally effectively applied and are rewarded more highly.

In bringing together richer skills and labour market data, the work of the UFS should enable us to better understand these issues and support the development of policies to eliminate these gaps. But an important question is how far eliminating skills mismatches – and indeed increasing skills more generally – can get us in terms of boosting productivity, especially in ‘left behind’ areas.

One potential risk of relying heavily on skills investments as a route to ‘levelling up’ is that higher skilled or more educated individuals may move away, meaning the areas in which the investments are made do not benefit fully from those investments. We already know this is the case for many graduates.

But our work suggests that, unlike graduates, those with lower level qualifications are highly likely to remain in or close to the areas in which they grew up. While around half of both graduates and non-graduates have moved at least locally by age 27, only one in six non-graduates moves to a different commuting area, compared to a one in three graduates. Amongst those who move, a majority of non-graduates move less than 5km, compared to more than 20km for graduates. This suggests that poorer performing areas would benefit from investments in skills, at least up to degree level.

Our work also suggests that while a substantial proportion (two-thirds) of the difference in wages (a proxy for productivity) across areas can be explained by the qualifications and skills of the individuals living in those areas, a significant minority (one-third) cannot. This highlights that investments in human capital (skills) on their own will not be enough to ‘level up’. Such investments will need to be supplemented with investments in other types of capital – the type and extent of which will differ from place to place – to ensure that the benefits of investments in education and skills can be fully realised.

Better data will help shed light on the extent of and reasons for skills mismatches, and hopefully lead to policies aimed at addressing these mismatches. However, reducing mismatches alone is unlikely to be sufficient to deliver the necessary boost to productivity if we are to eliminate differences across areas, or between the UK and its international competitors.

Without greater demand for skills, particularly in poorer performing areas of the country, we risk levelling down rather than levelling up. It is crucial that the UFS works closely with colleagues across government and in local areas to ensure that they support the ‘productivity’ as well as the ‘skills’ part of the board they are replacing.

By Blog Editor, on 18 May 2022

By Jo Blanden (University of Surrey/CEP, LSE), Matthias Doepke (Northwestern) and Jan Stuhler (Universidad Carlos III de Madrid)

This post was first published on the LSE Covid-19 blog on May 16th 2022, at https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/covid19/2022/05/16/what-do-we-know-so-far-about-the-effect-of-school-closures-on-educational-inequality/

Ninety-four percent of the world’s student population was affected by school and university closures in the spring of 2020, according to UNESCO. By May 2021, schools across countries had been fully closed for an average of 17 weeks. These closures varied widely in length, and were only partially determined by infection rates. Students in many developing nations, and in some US states, experienced closures that lasted more than a year — whereas there were no designated school closures at all in Belarus and Burundi. Closures were particularly long in China, Indonesia, and some countries in Southern Europe, but of similar intensity in most other countries.

School closures have been especially controversial in the US and Canada, where they have continued much longer than in other developed economies. In the US, closures were determined at the state or school district level, resulting in substantial variation in children’s experiences, as well as posing a challenge for the systematic collection of data. Evidence from mobile phone locations indicates that nine out of 10 schools were closed in April 2020, falling to 40 percent in September but then rising again to 56 percent in December of that year. Halloran et al. (2021) use school district-level data from 12 US states for the 2020–2021 academic year and show that shares of in-person schooling time varied from 9 percent in Virginia to 98 percent in Florida.

Learning is a cumulative process, where skills acquired at one life stage foster further learning later on. This means that learning losses, once incurred, are difficult to compensate for later. Many of the schoolchildren affected by the pandemic are therefore likely to enter adult life with fewer skills and lower educational attainment than they would have otherwise. This loss of what economists call ‘human capital’ will be reflected in lower lifetime earnings at the individual level, and could result in a lower stock of human capital and lower national income at the aggregate level for decades to come.

We are particularly interested in whether school closures increase educational inequality by differentially impacting children from different socio-economic backgrounds. There are two reasons why this might occur. First, the incidence of school closures themselves may vary by social background, for instance when public schools close while private schools attended by richer families stay open. Second, children from disadvantaged backgrounds might experience greater learning loss if their school closes. Children’s learning depends on inputs from educational institutions, parental inputs, and neighbourhood and peer effects. The potential for other inputs to compensate when schools are closed is likely to differ across families.

During the closures, the inputs provided by schools and teachers were often delivered via online education. Yet just how well virtual education can replace in-person schooling depends on factors such as having a reliable internet connection, functioning tablets or laptops, and a quiet work environment, all of which are more likely to be met in higher-income families. Parents also play an important role, and richer parents may not only be more capable of assisting their children in making up for lost time but also more likely to work from home, so they can help if need be.

School closures are not the only mechanism through which the pandemic may impact educational inequality. Its macroeconomic effects could decrease parents’ income and educational investments, reduce public spending on schooling, or affect the returns and incentives to acquiring education. The full impact of all of these changes on educational inequality will gradually emerge over the next few years, but researchers are already offering predictions based on several sources; from pre-pandemic evidence on the consequences of school closures, from early evidence from the pandemic, and from structural modelling of its long-run impact.

The pre-pandemic evidence suggests that COVID could increase educational inequality via two channels: a greater incidence of school closures in low-income neighbourhoods, and a greater learning loss conditional on closure among disadvantaged students. Indeed, early work on the pandemic supports both channels. Parolin and Lee (2021) show that school closures in the US in the autumn of 2020 were more common for students from ethnic minorities. School closures were also more widespread in institutions with lower third grade math scores, more homeless students, more students with limited English proficiency, and a larger share of students eligible for free or subsidised lunch. Halloran et al. (2021) confirm this picture, documenting that districts with a greater share of black students and a higher share of students receiving free lunches offered less in-person schooling.

In the UK, school closures are determined at the national level, but local mitigation procedures led to varying incidence, as groups of children were required to isolate if a positive case was detected in their “bubble.” Eyles and Elliot Major (2021) show that in autumn 2020, these localised measures led to nine days of missed schooling in the poorest areas compared to only two days in the most affluent municipalities. This evidence suggests that variation in the incidence of school closures could exacerbate educational inequalities.

Some alarming direct evidence is emerging on the impact of school closures in the early phases of the pandemic. Engzell, Frey, and Verhagen (2021) find that in the Netherlands, eight weeks of online rather than in-person learning led to 0.08 of a standard deviation lower test scores for students aged eight to 11. The impact is 40 percent larger among those in the least educated homes, suggesting that the pandemic not only increased educational inequality, but that disadvantaged children’s skills actually deteriorated. Tomasik, Helbling, and Moser (2021) analyse improvement in student skills in German-speaking Switzerland over the initial eight-week school closure starting in March 2020, compared to the eight weeks just prior. On average, primary school pupils learned half as much under distance learning, and there was more inequality in their progression. In particular, those with higher ability going into the pandemic saw stronger effects. Students in secondary school learned at the same speed as before.

Maldonado and De Witte (2020) provide evidence on 5th graders in Flemish Belgium who experienced seven weeks of school closure, partially replaced with online teaching. This period led to reduced test scores, equivalent to 0.19 of a standard deviation in maths and 0.29 of a standard deviation in Dutch compared to earlier cohorts. Students performed worse than if they had simply retained their initial knowledge, suggesting a slide in skills. The authors observe weak effects on inequality, with no differences across schools by initial average test scores or by the school’s social mix for math outcomes, and only slightly larger effects for poorer schools in Dutch.

These results suggest that school closures during the pandemic had greater effects on test scores than one might have expected based on extrapolations from prior evidence. Children’s learning may have been affected not just by the school closures themselves but also by other effects of the crisis, such as the disruption of peer interactions or increased anxiety during the pandemic. Improved virtual instruction might have helped reduce learning losses as the pandemic wore on, but uneven engagement has the potential to worsen inequalities even further. Lewis et al. (2021) point to “pandemic fatigue” as an explanation for why they observe more learning loss in the spring of 2021 compared to six months previously, and cite evidence that students were more likely to report not liking school in the winter of 2021 compared to the start of the academic year.

Halloran et al. (2021) show that proficiency rates in English and maths were on average 14 percentage points lower during the pandemic. By associating variation in time spent in different learning modes over the 2020/2021 academic year (remote, hybrid, in-person) with district-level information on test scores, the authors conclude that this gap would have only been four percentage points if schools had remained open throughout the period, though the effects are likely to be downward biased due to missing data. The authors see larger effects in districts with more students of colour and a greater number of students eligible for free school meals.

Underlying the impact of school closures on overall learning and educational inequality are several distinct mechanisms. First, the availability and quality of virtual learning offered by schools is clearly important. Second, there may be differences in parents’ ability to support virtual learning and to compensate for the lost investments from schools. Third, the work put in by the students themselves matters as well. Clark et al. (2021) consider evidence from China and show that children who have access to online learning through their school do 0.22 of a standard deviation better on tests that follow the end of a seven-week period of school closures. While effects by family background are not reported, the authors find that effective online learning is especially beneficial for low achievers. This observation suggests that inequalities in access to online learning may in part drive inequalities in the impact of school closure.

Andrew et al. (2020) survey parents in the first period of English school closures and find that primary school students in the tenth percentile of the family income distribution did about 35 minutes less learning per day than those from median-income families, and 1 hour and 10 minutes less that a child from a family in the 90th percentile of the income distribution. Similarly, Grewenig et al. (2021) and Werner and Woessmann (2021) find that during school closures, low-achieving students in Germany disproportionately replace learning time with less productive activities, such as playing video games.

School closures during the pandemic affect learning through three channels. First, there is a decline in the overall efficiency of skill accumulation because remote learning is less effective than in-person instruction. Second, parents have to replace some inputs that are usually provided by teachers. Parents’ ability to provide these inputs depends on time constraints: parents who are able to work from home during the pandemic have an easier time helping their children with school work than do essential workers who must work outside the home. Third, peer effects and peer-group formation is also disrupted during the pandemic.

Agostinelli et al. (2022) assess the contribution of these channels to educational inequality. All three channels are found to contribute to a widening of educational inequality. While all parents increase their time investments during the pandemic, the ability of low-income parents to respond is hampered by the fact they are much less likely to have jobs that can be done from home. Hence, inequality in parental input increases between high- and low-income neighbourhoods. Inequality in peer effects also rises, in part because children from low-income neighbourhoods lose the ability to meet more high-ability peers at school, and in part because the effect of losing any peer connection on learning is worse for children already struggling in school.

In the US, secondary and public schools were closed for longer periods than elementary and private schools, respectively. Fuchs-Schündeln et al. (2021) predict that the earnings- and welfare losses will be largest for children who started public secondary schools at the onset of the crisis. Welfare losses are smaller for children from richer families, who are more likely to send their children to private school. The authors further suggest that a policy intervention to extend schooling (by shortening the summer breaks in future years) would raise tax contributions sufficiently to be self-financing.

Survey evidence shows that considerably fewer children continued learning activities during school closures in low-income countries, with particularly large reductions in sub-Saharan Africa. Limited education funding and less access to communications technology implies that few children had access to virtual lessons during school closures. Many children essentially received no education at all during prolonged school closures, so that the total learning loss is likely to be severe. Moreover, beyond the size of the learning loss, a given learning loss is likely to have a greater long-run economic impact in low-income countries. This is partly due to demographic reasons. Low-income countries have much younger populations than do high-income countries, which means that cohorts of children finishing school are large compared to the adult labour force.

Commentators on both sides of the Atlantic have called for policy action to help offset the damaging effects of school closures. These primarily focus on what schools can do once children return. Proposed interventions include increased school funding, providing small group instruction, and lengthening the school day or year. All of these have potential, with targeted small group instruction shown to be especially fruitful. Evidence suggests that additional days spent at school raise test scores for poorer students, but the likelihood of diminishing returns means the optimal length of the post-pandemic school year is unclear.

It has already become clear that the pandemic has had a major negative impact on many children’s learning and is likely to have substantially increased educational inequality within the affected cohorts. Tracing the effect of this shock over the following years and contributing to the design of effective policy responses represents an important challenge for future research.

This post is an edited extract from Education inequality: a Centre for Economic Performance discussion paper, by Jo Blanden, Matthias Doepke, and Jan Stuhler, April 2022.

By Blog Editor, on 11 February 2022

John Jerrim, UCL Social Research Institute

This blog post first appeared on the IOE blog.

In the third blog post in this series, I started to investigate socio-economic differences in the inputs into young people’s financial skills, focusing upon the role of parents.

Schools, of course, also have a key role in helping to develop children’s financial skills. Therefore, in this final blog of the series, we turn to socio-economic gaps in the provision of financial education within primary and secondary schools.

Big gaps in primary schools

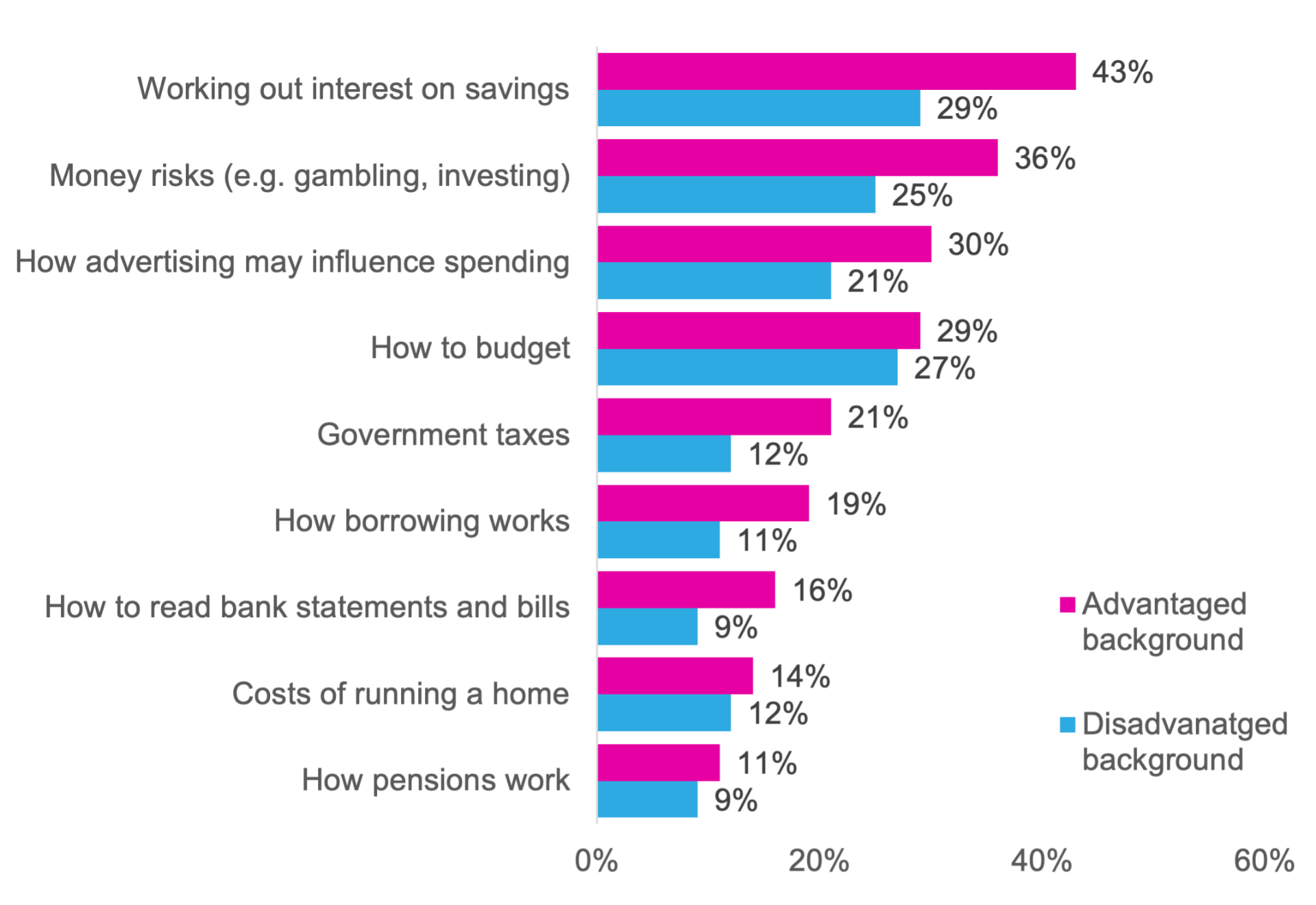

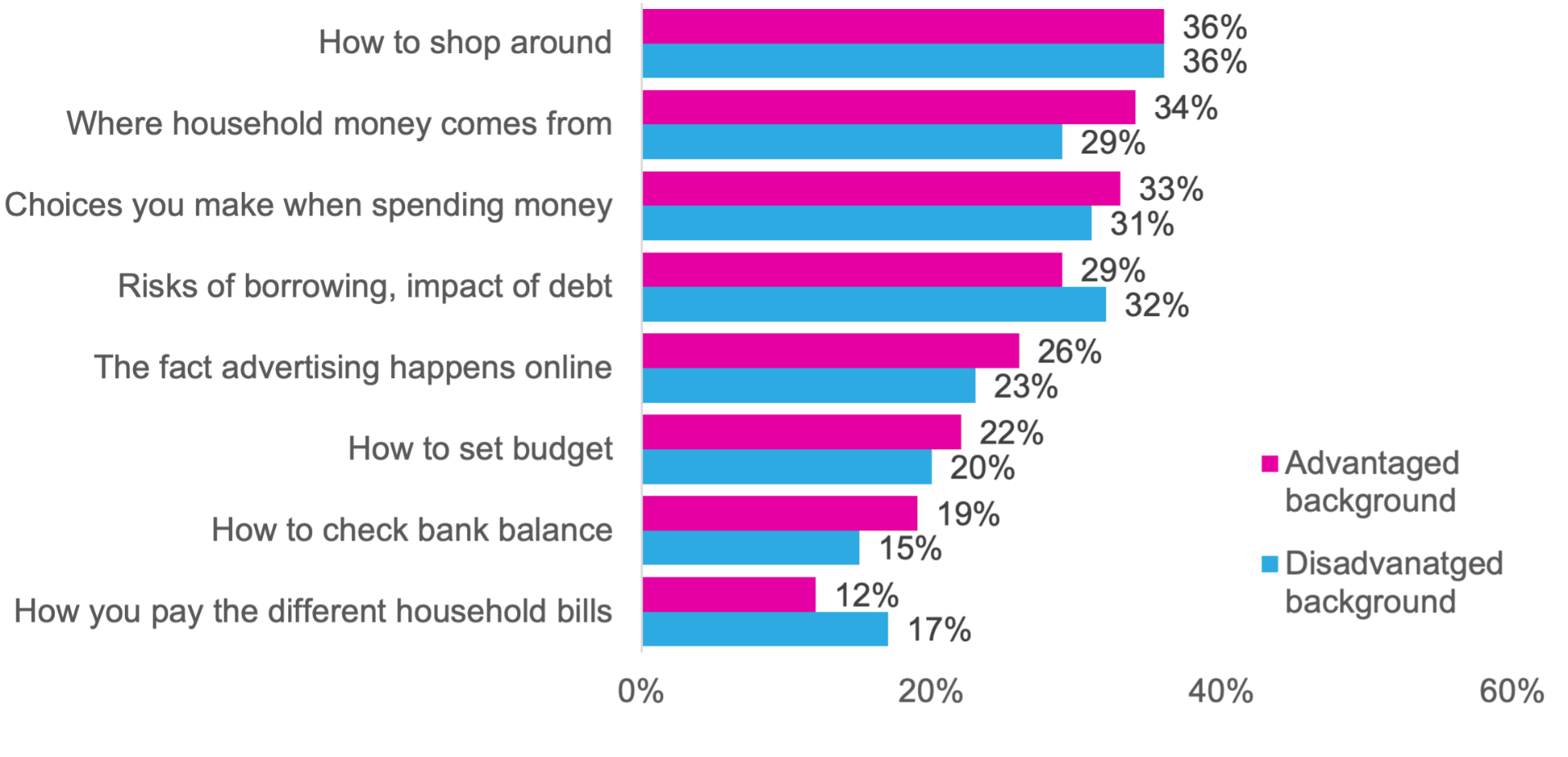

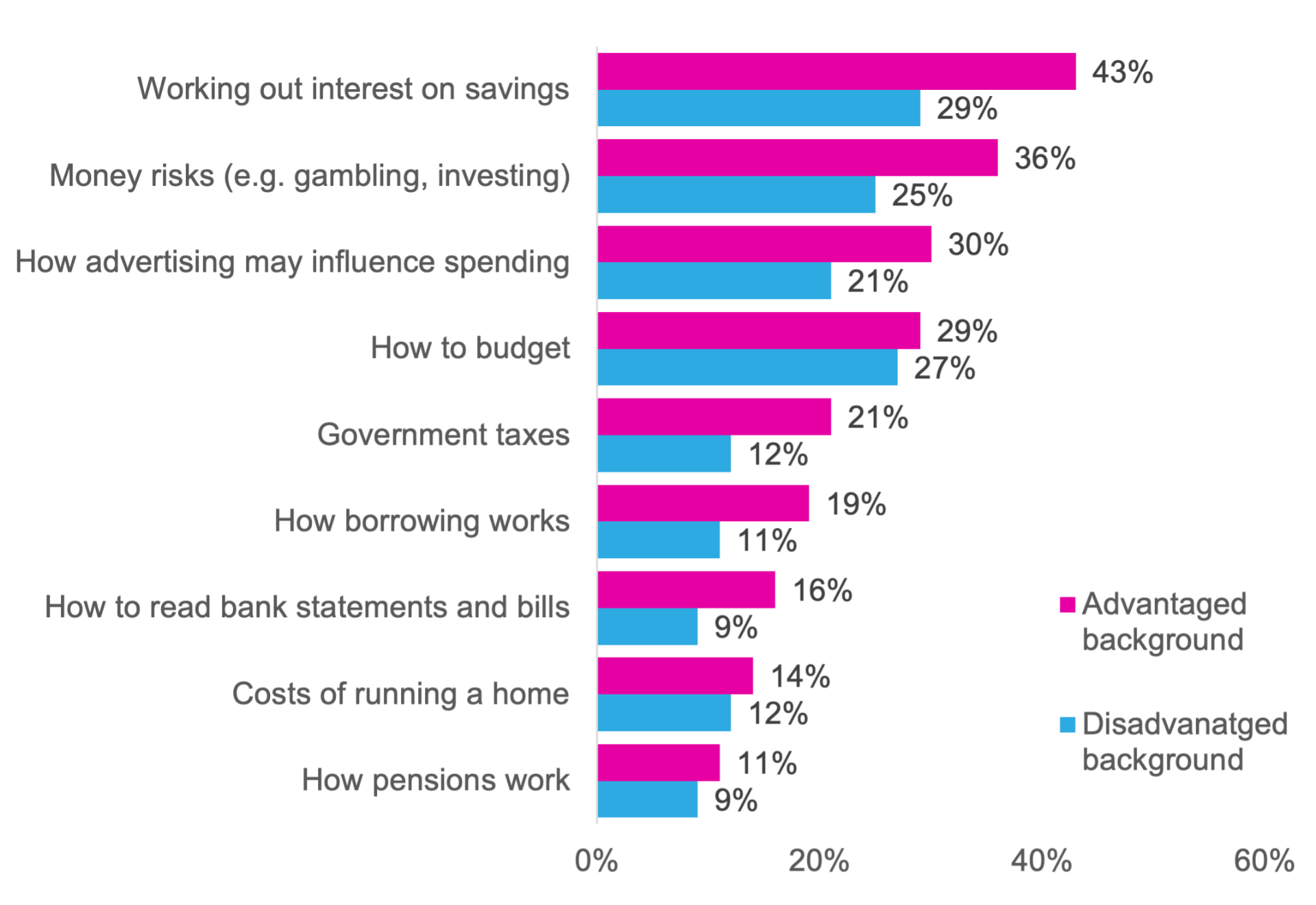

Let’s start by looking at what happens in primary school. Figure 1 illustrates the percent of primary pupils who say they have been taught various financial skills at school, stratified by socio-economic background.

There are two striking results.

First, there are consistently large socio-economic gaps. For instance, children from advantaged socio-economic backgrounds are much more likely to report that they have been taught skills such as working out change from shopping (67% versus 54%), saving money (43% versus 28%), and the difference between the things you “need” and things you “want” to buy (36% versus 27%) than their disadvantaged peers.

Second, it is notable how only quite a small proportion of primary school children are taught some really key financial skills at school. For instance, even amongst higher socio-economic status families, only around one in five primary children are taught about bank accounts, how to keep track of spending and saving, and how to spot that advertising is trying to sell them something.

Interestingly, Figure 2 illustrates how a similar pattern emerges during secondary school as well. This presents the clearest evidence to date that the financial education provided to socio-economically advantaged and disadvantaged pupils differs significantly throughout their time at school. Moreover, some key basic financial life skills – such as learning how to budget, how to read bills, and understanding how borrowing works – are only taught by schools to a minority of disadvantaged pupils.

Figure 1. Socio-economic differences in the provision of financial education during primary school

Figure 2. Socio-economic differences in the provision of financial education during secondary school

With respect to the socio-economic gap in financial education provision during primary school, it is also notable how it seems to increase over time, between age 7 (end of Key Stage 1) and age 10 (nearing the end of Key Stage 2). This is illustrated in Figure 3, which combines responses to various questions into a scale, and reports changes in the socio-economic gap over time as an effective size.

In other words, while seven-year-olds from rich and poor backgrounds report receiving similar amounts of financial education at school, this gap in provision increases significantly during Key Stage 2.

Figure 3. Change in socio-economic status gap in “money planning” education provided to primary school pupils

Notes: “Money planning” includes topics such as saving, how to keep track of spending and saving, how to keep money safe and borrowing from banks.

Increase the focus of financial education in the school curriculum

The above suggests that greater time needs to be made in the school curriculum to provide financial education to young people – particularly those from lower socio-economic backgrounds.

Currently, only a minority of low-income children report receiving any education through their school in some key financial life skills. This puts them at a disadvantage compared to their more advantaged peers, with the gap in provision particularly pronounced towards the end of primary school.

One option could be to integrate financial education skills into the Key Stage 2 tests (with the most obvious choice being mathematics). This would provide schools with a clear incentive to ensure young people develop these vital life skills, which currently seem to be pushed out of the school curriculum.

By Blog Editor, on 11 February 2022

John Jerrim, UCL Social Research Institute

This blog post first appeared on the IOE blog.

In the previous blog post in this series, I investigated socio-economic differences in young people’s financial skills. This focused upon the types of financial questions that young people from advantaged backgrounds can successfully answer, that their peers from disadvantaged backgrounds can’t.

In this next post, I start to consider socio-economic differences in one of the key inputs into the development of young people’s financial skills – the role of their parents. Are there certain things that higher-income parents do with their offspring to nurture their financial skills, that lower-income parents do not?

Let’s take a look (with further details available in the academic paper here).

Differences in knowledge

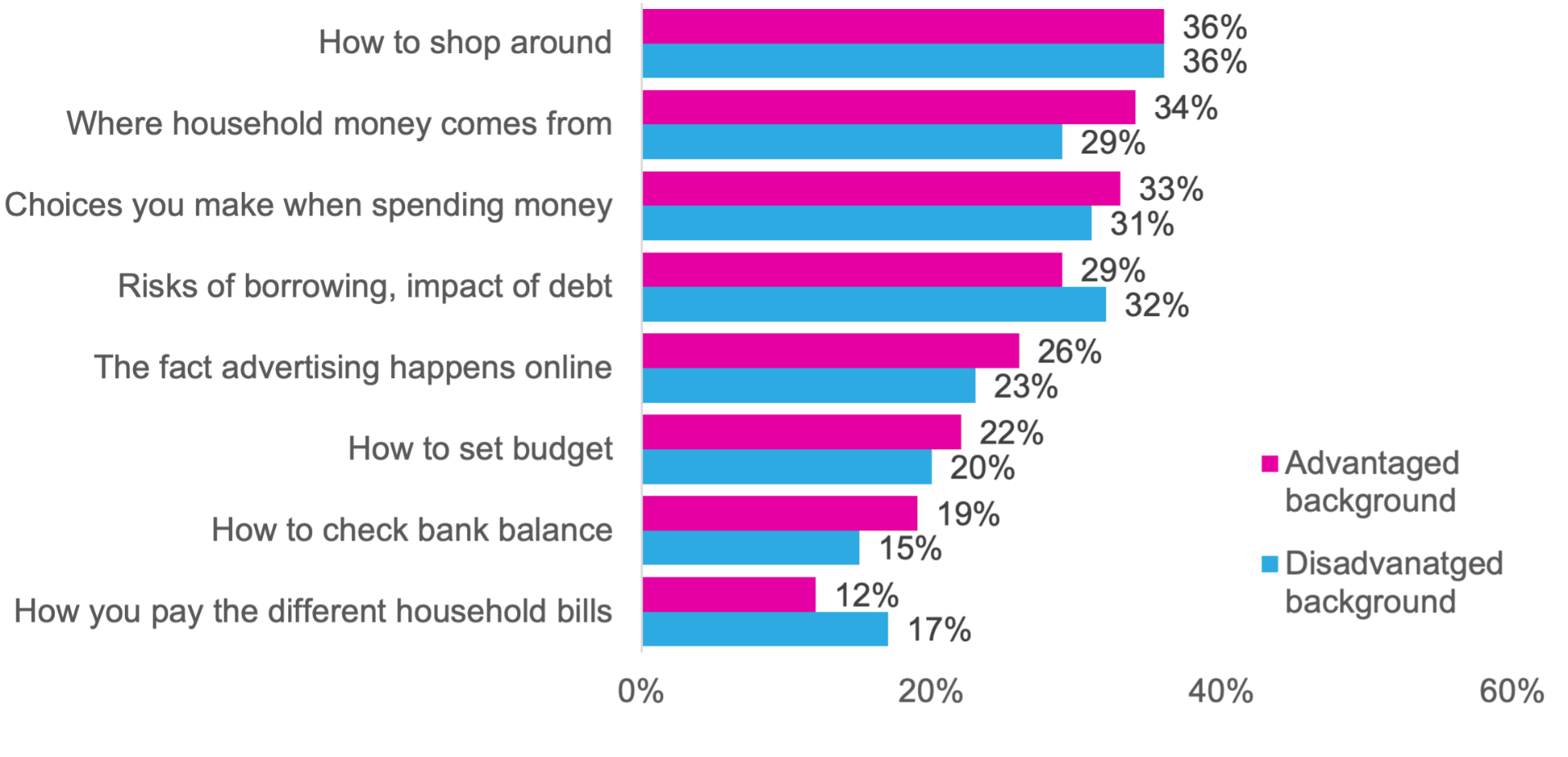

Figure 1 presents the percent of parents who say they do various financial activities “often” with their children, divided by socio-economic group.

Figure 1. Socio-economic differences in parent-child conversations and demonstrations of money use

Note: Figures refer to the percentage of parents who report that they “often” talk to or who show their child how to do the following things with money.

Although higher socio-economic parents are slightly more likely to regularly do most of the activities with their offspring, differences are generally quite small. For instance, although high socio-economic status parents are more likely to talk to their child about where their household money comes from than low socio-economic status parents (34% versus 29%) and the fact that advertising happens online (26% versus 23%) there is no difference in – for instance – showing their child how to shop around.

There are also certain areas that lower socio-economic status parents are more likely to talk to their children about, such as the risks of borrowing, the impact of debt, and how they pay for different household bills.

So, on the whole, socio-economic differences in the informal types of financial education parents provide their children are relatively muted. This point is reiterated by another finding from the survey – that the vast majority of parents recognise the importance of teaching their children about money, regardless of socio-economic background (see the top row of Table 1 below).

Where there does seem to be a notable socio-economic difference, however, is in parents’ confidence in their ability to effectively teach their children about money.

For instance, as Table 1 illustrates, more affluent parents tend to have greater confidence in being able to teach their child about how to manage money (65% versus 52%), that they can act as a good financial role model (65% versus 52%) and that they will be able to affect how their child will behave with money in the long-term (46% versus 37%), than disadvantaged parents.

Table 1. Socio-economic differences in parental views and confidence in teaching their children about money

| |

Disadvantaged background |

Advantaged background |

| % who believe it’s important to teach children about money |

85% |

88% |

| % very confident in talking to your child/children about how to manage money |

52% |

65% |

| % who strongly agree they can be a good role model for child around money |

32% |

47% |

| % who strongly believe they can affect how child will behave around money when they grow up. |

37% |

46% |

| % who don’t know how to talk to my child/children about money |

13% |

13% |

Now, such differences could either reflect that (a) higher socio-economic parents are indeed able to teach their children about money more effectively or (b) they are simply more confident in doing so.

Either way, any socio-economic gap in financial skills does not seem likely to be linked to the frequency with which high and low-income parents interact with their children about money – as they report having money conversations and conducting money demonstrations equally regularly. Rather, it seems more likely to be related to low-income parents’ ability to provide effective financial education to their offspring, either through a lack of skills or lacking in confidence to do so.

By Blog Editor, on 10 February 2022

John Jerrim, UCL Social Research Institute

This blog post first appeared on the IOE blog.

The first blog post in this series illustrated how there are substantial socio-economic gaps in children’s financial literacy skills, with these differences emerging before the start of primary school.

But what exactly can rich kids do – in terms of their financial knowledge and skills – that poor kids can’t?

This blog post takes a closer look.

Differences in knowledge

As part of the Children and Young People’s Financial Capability Survey, young people age 11 and above were asked whether they knew the correct term for various financial concepts, such as “the money people pay to government” (taxes) and “the amount the price of things in shops does up by”.

The percentage of young people who provided the correct response – stratified by socio-economic group – can be found in Figure 1. This provides a clear and consistent story of there being around a 10 to 15 percentage point difference on each of the concepts asked; young people from disadvantaged backgrounds have consistently weaker knowledge across a range of financial concepts.

Figure 1. Inequality in young people’s knowledge of different financial concepts (children age 11 – 17)

How about how money works “in practice”? Young people were also informally tested about their knowledge of how interest on savings work. The exact questions they were asked can be found in Table 1.

Around one-in-three 11-17-year-olds from low socio-economic status families could not work out the amount of money they would have in their savings account with an interest rate of two percent. This is compared to just 14% of children from affluent family backgrounds.

Even fewer disadvantaged children – around two-thirds – failed to understand the concept of a real savings rate, and how inflation erodes the purchasing power. Again, as Table 1 illustrates, the socio-economic gap here is particularly stark.

Table 1. Inequality in understanding interest rates (children age 11 – 17)

|

Low SES |

High SES |

| Suppose you put £100 into a savings account with a guaranteed interest rate of 2% per year. You don’t make any further payments into this account and you don’t withdraw any money. How much would be in the account at the end of the first year? |

68% |

86% |

| If the inflation rate is 5% and the interest rate you get on your savings is 3%, will your savings have more, less or the same amount of buying power in a year’s time? |

31% |

53% |

But what about the consequences of not keeping up with paying important bills? This may have more salience for young people from disadvantaged backgrounds than advantaged backgrounds, given how their parents are more likely to face such financial difficulties.

Interestingly, in this area, socio-economic differences are a lot less pronounced, as illustrated by Figure 2.

Figure 2. Inequality in young people’s understanding of the consequences of not paying council tax (children age 14 – 17)

Almost all children, regardless of their socio-economic status, understood that failing to pay council tax has consequences, and that the government won’t simply pay it for you.

But only around one-in-three understood that this is a criminal offence, which could result in a custodial sentence, with the percentage actually slightly higher for those from disadvantaged backgrounds. Similarly, only around half of 14-17-year-olds realised that possessions may be seized by a debt collector, with again only a comparatively small difference between socio-economic groups.

Conclusions

Although disadvantaged children’s knowledge of key financial concepts is weaker than their more advantaged peers, they seem to be equally tuned in to the consequences of failing to meet important financial commitments.

Nevertheless, it is somewhat concerning the way there do appear to be significant gaps in disadvantaged children’s financial knowledge. Many cannot work out simple interest rate calculations, with most not understanding that inflation erodes the purchasing power of money. More than half of disadvantaged teenagers also do not grasp the full severity of not paying their taxes due.

Given the potential long-term consequences of such weak financial skills, more needs to be done to improve disadvantaged young people’s understanding of money and how it works.

Close

Close