How do we fund widening participation outreach that works?

By Blog editor, on 8 April 2024

By Dr Paul Martin

Last week the Secretary of State for Education, Gillian Keegan, issued DfE’s annual guidance to the Office for Students (OfS) on strategic priorities grant funding, which includes centralised investments to widen access to higher education. Amongst this year’s announcements was a reduction in funding for the ‘Uni Connect’ programme – which is designed to support students from more disadvantaged backgrounds into higher education – by £10 million per annum.

This most recent reduction is the latest in a series of cuts which has reduced Uni Connect’s budget from £60 million in 2020 to just £20 million today, and represents the continuation of more than 20 years of dithering by governments of various political parties concerning the extent to which they should fund centralised widening participation (WP) outreach programmes. From the AimHigher initiative (which launched in 2004) through to Uni Connect today, governments never seem to have been able to agree on how much money to invest in these programmes or how long to fund them for. As observed in the recent Public First evaluation of Uni Connect, the constant uncertainly surrounding the programme has led to serious challenges when it comes to planning activity and retaining staff.

The lion’s share of outreach spending

These centralised programmes represent only a minority of the money spent on widening participation, though, with the majority spent by individual universities themselves.

From 2012 onwards, there was a considerable increase in the number of WP outreach activities delivered by universities themselves, with universities only able to charge the new maximum tuition fees of £9,000 per year if a proportion of fees above £6,000 were allocated to widening participation activities. Today, the situation is very similar – universities may only charge fees above £6,165 (up to a maximum of £9,250) if they have an ‘Access and Participation Plan’ in place which spells out how they will use their additional fee income to improve equality of opportunity. Figures reported by the OfS show that in 2022-23 England’s 198 HE providers pulled in more than £3.4 billion from fees above the basic level of £6,165 and that 25% of this higher fee income (or £859 million) was spent on ‘access and participation investment’ (including financial support for students). For initiatives that support ‘access’ in particular, an estimated £185 million was spent across the providers.

Good news and bad news

While not great news, therefore, a reduction of £10 million in the Uni Connect budget represents a relatively small reduction in our overall annual spend on WP access initiatives. Of greater concern is that we don’t really know whether we’re getting the most bang for our buck in terms of the way we use this relatively large pot of money to improve equality of opportunity.

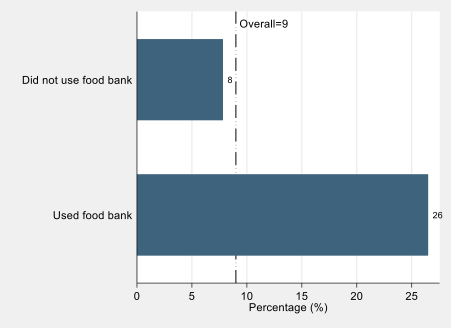

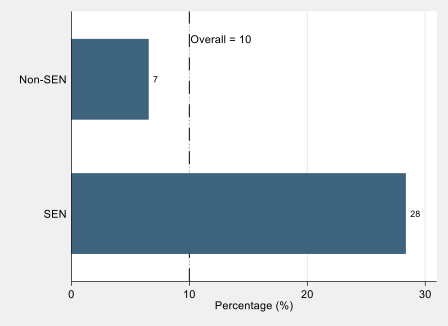

For many years we have presided over something of a “good news and bad news” situation concerning access to HE for disadvantaged young people. As pointed out in a new CEPEO briefing note on this issue, the latest DfE widening participation statistics show that the proportion of free school meals (FSM) eligible school pupils progressing to HE continues to increase year after year. This is the good news.

The bad news is that overall, there does not appear to have been any narrowing of the gap in terms of FSM versus non-FSM eligible participation rates in HE. In fact, the percentage point gap in participation most recently reported by the DfE is the widest on record since they first began collecting the data 16 years ago. This is true whether we look at access to HE in general, or access to more selective ‘high-tariff’ universities. The percentage point gap in participation by FSM status might not be the only barometer we are interested in, but the lack of progress on this metric (and only minimal progress on reducing gaps in participation between those from different neighbourhoods) sits somewhat awkwardly alongside over £200 million of annual expenditure on this issue.

The importance of evaluation

We should not necessarily infer from these statistics that WP outreach has been unsuccessful. Whilst the proliferation of WP outreach has not coincided with a narrowing of the FSM participation gap, we should bear in mind the possibility that the FSM gap might be even wider still today were it not for the influence of WP outreach. But the fact that we can’t answer this question adequately is a problem: we still don’t know anywhere near enough about whether this significant investment in outreach has been well spent, or whether it could have been more successfully deployed in other ways. How can we change this?

First, we need to significantly improve our efforts to evaluate WP outreach initiatives effectively. Often, we don’t really know what works, because of the lack of experimental or quasi-experimental design in the implementation of WP programmes. We won’t be able to make significant improvements to the evidence base until this happens.

Second, we need to ensure that WP outreach programmes are targeted effectively and are recruiting the right people to take part. Recent research has evaluated the ‘Realising Opportunities’ outreach programme, which focuses on supporting disadvantaged young people to progress to more selective research-intensive universities. Programme participants were found to be much more likely to progress to these research-intensive universities when compared to predictions made by statistical modelling which took into consideration participants’ prior attainment and personal characteristics. Part of the success of the programme hinged on the fact that most participants would be unlikely to progress to research-intensive interventions in the absence of the intervention, leaving a big margin for improvement.

In contrast, some other programmes may not be so well targeted. For example, recent evaluations by TASO of online and in-person ‘summer school’ outreach activities found that the programmes were unlikely to change participant behaviour given that most participants were already on a pathway to HE even prior to taking part in the interventions. If outreach is to be successful, it has to avoid merely preaching to the converted.

Finally, we can improve the evaluation of WP outreach by making greater use of the rich education administrative data that we are lucky to have access to in England. The Realising Opportunities research used linked National Pupil Database (NPD) and the Higher Education Statistics Agency (HESA) undergraduate record data, which remain underexploited in research in this area. The recent evaluation of Uni Connect mentioned above made use of the ‘HEAT’ (Higher Education Access Tracker) dataset which is a huge administrative record concerning participants in a large number of WP outreach programmes over many years. However, as this dataset was only available on its own, a comparison could only be made between those who had engaged more and less intensively with outreach programmes, with no comparison made with those who had not taken part in outreach at all.

If we can successfully link together datasets such as HEAT with the NPD and HESA records, we will have a more accurate view of the extent to which outreach participation makes a difference when all other observable characteristics of students are equal. If and when we are able to throw LEO earnings data into the mix too, we ought to be able to gauge the extent to which WP outreach programmes fulfil their ultimate purpose of supporting disadvantaged young people through the education system and into well paid careers. At this point we would have the clearest insight yet into which particular programmes offer the best return on investment.

Close

Close