Turbulence on the glide path: A-level results 2022

By Blog Editor, on 18 August 2022

Jake Anders and Lindsey Macmillan

This year sees A-level (or equivalent) results for the cohort of pupils who were on the cusp of sitting their GCSEs in 2020 when exams were first cancelled due to the Covid-19 pandemic. Now exams are back, much to the dismay of many who believe that teacher-assessed grades should become the new norm. Here at CEPEO, we’ve regularly made the case for externally set and externally marked exams, based on academic evidence that teacher assessment leads to biases against certain groups. But what has the return of exams meant for results?

The implementation of a “glide path” has been successful – generally speaking, the results are pretty much halfway between those from 2019 and 2021. While the headlines are all focused on grades being down on last year, they are, if anything, slightly more generous than might have been predicted given the intention to deal with half of the grade inflation from teacher assessment seen in 2020 and 2021. This will be driven by the fact that these weren’t strictly exams in the 2019 sense – leniency in marking was encouraged and pupils had extra information in advance of exams, which may also have had other consequences that we’ll come back to shortly.

They don’t mean that learning loss for these students is no longer a problem – since the overall level of grades was decided by that “glide path”. As such, we do not know if this group of students would have achieved as good grades as their peers in 2019 despite the disruption. This is particularly the case given some remaining incomparability with 2019 around leniency in marking and advance notice of exam content. Ongoing concerns about learning loss, its consequences, and support for catching up need to be informed by other evidence, not allayed by these results.

Regional differences present a worrying picture for inequalities – the gap in the proportion of pupils achieving A or above at A level has increased between regions, from 7.3ppts in 2019 to 8.2ppts in 2022. So, London and the South East are continuing to pull away from other areas while the North East and Yorkshire and the Humber are particularly being left behind. This trend of Southern regions pulling ahead was also evident in the Key Stage 2 data released last month, and will provide a big headache for a government that has put ‘levelling up’ at the heart of what they plan to achieve.

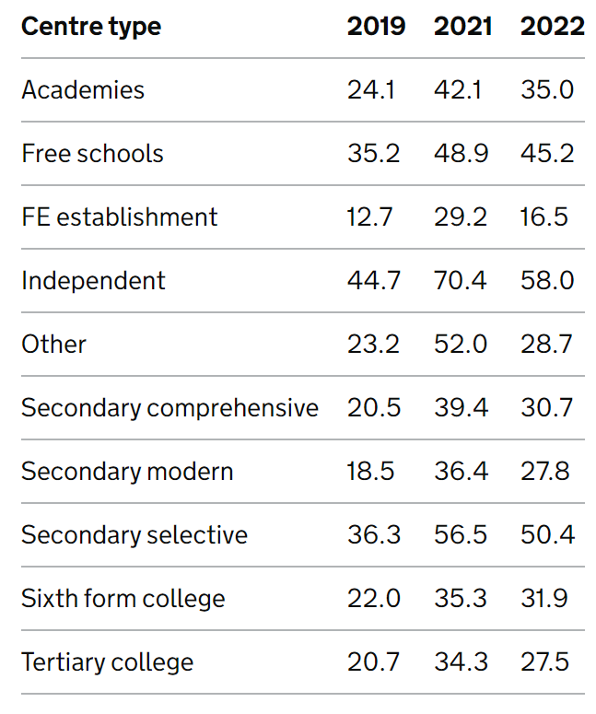

Source: JCQ

A mixed picture across centre type – FE colleges and independent schools have seen the biggest absolute declines in the proportion of A-levels awarded A or above. For independent schools, this is not altogether surprising given their huge grade inflation from 2019 to 2021, which saw a massive 25.7ppt increase in the proportion of pupils achieving A or above over the period, and over 70% of all private school pupils awarded an A or above in 2021. This number has returned to a more ‘reasonable’ 58% for 2022. Two points to make here: First, this highlights the extent of grade inflation in this type of centre during the period of teacher assessment. Second, this is still an extremely high proportion of pupils achieving a grade A or above, which could be indicative of private school pupils being better placed to make use of the additional information on exam content made available in advance this year, as well as the advantages that private school pupils had in terms of relative learning loss during the pandemic.

FE colleges are far more puzzling – they have seen a similar absolute decline in the proportion achieving A or above, but from a much lower base. They saw a 16.5ppt rise in pupils achieving A or above from 2019 to 2021, only 29.2% reached this level of achievement by 2021. This has fallen back down to 16.5% in 2022. Somewhat speculatively, it seems plausible that students in FE colleges were, in contrast to those at independent schools, particularly badly affected by the disruption wrought by COVID-19.

Source: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/guide-to-as-and-a-level-results-in-england-summer-2022

Grammar schools, on the other hand, have found themselves performing at a level that is almost comparable with that seen in 2021, despite the different type of assessment, and 14.1ppts higher than 2019. One explanation for this could be, like private schools, that grammar school teachers and pupils were better placed to use the additional information released in advance of exams this year, focusing on a far narrower set of curricula. Additionally, this may be the first indication (through exam results at least) that pupils from more advantaged backgrounds were less constrained by learning loss during the pandemic.

In many ways, these results have not told us much we did not already know – it was already pretty clear that independent school grades, especially, were artificially inflated by teacher assessment, although the percentage coming back down now challenges those who told a tale of Covid learning loss advantages last year. We already knew that the impacts of COVID-19 disruption were likely to be unequal. And we already knew that this was going to be an extremely tough transition for those young people in the middle of it, rightly proud of what they have achieved through difficult circumstances, but unsure of what it all means compared to their peers one year above or below them.

Close

Close