How prepared are we for the roll-out of the early education entitlements? No-one really knows …

By Blog Editor, on 24 April 2024

By Dr Claire Crawford

Today saw the release of a report from the National Audit Office – the public spending watchdog – assessing the Department for Education’s (DfE’s) preparedness for the rollout of the new early education entitlements. We’ve all read and heard the media reports about how unprepared local authorities and providers are for what’s coming. Warning bells have been sounded for some time. What do things look like from inside the Department? Are they as bad as they seem?

Some of the figures are certainly eye-watering: an additional 85,000 places required by September 2025, delivered by an additional 40,000 staff. But the uncertainty over these estimates is at least as large: while DfE’s central estimate for the number of additional staff required by September 2025 is 40,000, this could be as high as 64,000 or as low as 17,000 according to the Department’s estimates.

The report certainly doesn’t make easy reading for those charged with implementing this policy. But one of the main takeaways for me is just how much effort has gone into figuring out how many more places and staff will be required to deliver on this huge promise – which is not an easy task. We have virtually no evidence internationally, let alone in the UK, that tells us how responsive parents of 0-2 year olds are to childcare subsidies. Very few other countries in the world have done anything like what we are attempting in England at the moment. We just don’t know whether there are reservoirs of parents – let’s face it, mostly mothers – with very small children just itching to get back into the workforce or to increase their hours. Or whether, actually, when push comes to shove, they would prefer to stop working, or to work part-time, while their children are young. We are about to test that hypothesis on a grand scale.

But unlike researchers who can just sit back and wait to evaluate what happens post hoc, policymakers have to try to estimate parental demand, to understand just how hard they (and local authorities) need to work to ensure there are enough places (and enough staff to deliver those places). The Department is doing its best to answer this exam question. (Although it is disappointing to hear that a planned pilot was ruled out for affordability reasons – what a missed opportunity!) Their estimate of the number of entitlement ‘codes’ requested by parents – which they need in order to claim the funded hours for their child – in advance of the initial rollout of 15 hours of care for 2-year-olds, which began earlier this month, is, frankly, scarily accurate (246,833 against a prediction of 246,000). It’s not clear from the NAO report when that prediction was made, and of course this is at the easier end of the prediction scale: this first phase of the rollout was always going to largely be about subsidising families who were already using formal childcare, which we have data about. Some of the children who will be eligible for the rollout in September 2025 haven’t even been born yet.

One other nugget that leapt out at me from the report is that for a policy whose primary motivation is to improve the labour supply of parents, actually the Department expects the majority of benefits (around two thirds) to arise not from the short-term benefits of higher parental labour supply, but from the much longer-term potential benefits to the children themselves, who may be accessing more formal early education than they otherwise would have done as a result of the policy.

It would be wonderful to get under the hood of these estimates and see how much of this is predicated on them accessing high quality provision – whose importance is somewhat lost because of the focus on labour supply. But, in any case, because the policy is targeted on children in working families, these benefits will not be accruing to the most disadvantaged children in society. The Department clearly recognises the risk that this will increase inequalities – indeed, the report reveals that they explored extending entitlements for disadvantaged children alongside the extension for working families during pre-budget discussions with HM Treasury. That clearly didn’t end up being part of the government’s chosen approach. But the absence of such a countervailing policy puts the onus even more firmly back on the Department to take other policy action over the coming years to prevent the gap between disadvantaged children and their more advantaged peers from widening even further.

How do we fund widening participation outreach that works?

By Blog editor, on 8 April 2024

By Dr Paul Martin

Last week the Secretary of State for Education, Gillian Keegan, issued DfE’s annual guidance to the Office for Students (OfS) on strategic priorities grant funding, which includes centralised investments to widen access to higher education. Amongst this year’s announcements was a reduction in funding for the ‘Uni Connect’ programme – which is designed to support students from more disadvantaged backgrounds into higher education – by £10 million per annum.

This most recent reduction is the latest in a series of cuts which has reduced Uni Connect’s budget from £60 million in 2020 to just £20 million today, and represents the continuation of more than 20 years of dithering by governments of various political parties concerning the extent to which they should fund centralised widening participation (WP) outreach programmes. From the AimHigher initiative (which launched in 2004) through to Uni Connect today, governments never seem to have been able to agree on how much money to invest in these programmes or how long to fund them for. As observed in the recent Public First evaluation of Uni Connect, the constant uncertainly surrounding the programme has led to serious challenges when it comes to planning activity and retaining staff.

The lion’s share of outreach spending

These centralised programmes represent only a minority of the money spent on widening participation, though, with the majority spent by individual universities themselves.

From 2012 onwards, there was a considerable increase in the number of WP outreach activities delivered by universities themselves, with universities only able to charge the new maximum tuition fees of £9,000 per year if a proportion of fees above £6,000 were allocated to widening participation activities. Today, the situation is very similar – universities may only charge fees above £6,165 (up to a maximum of £9,250) if they have an ‘Access and Participation Plan’ in place which spells out how they will use their additional fee income to improve equality of opportunity. Figures reported by the OfS show that in 2022-23 England’s 198 HE providers pulled in more than £3.4 billion from fees above the basic level of £6,165 and that 25% of this higher fee income (or £859 million) was spent on ‘access and participation investment’ (including financial support for students). For initiatives that support ‘access’ in particular, an estimated £185 million was spent across the providers.

Good news and bad news

While not great news, therefore, a reduction of £10 million in the Uni Connect budget represents a relatively small reduction in our overall annual spend on WP access initiatives. Of greater concern is that we don’t really know whether we’re getting the most bang for our buck in terms of the way we use this relatively large pot of money to improve equality of opportunity.

For many years we have presided over something of a “good news and bad news” situation concerning access to HE for disadvantaged young people. As pointed out in a new CEPEO briefing note on this issue, the latest DfE widening participation statistics show that the proportion of free school meals (FSM) eligible school pupils progressing to HE continues to increase year after year. This is the good news.

The bad news is that overall, there does not appear to have been any narrowing of the gap in terms of FSM versus non-FSM eligible participation rates in HE. In fact, the percentage point gap in participation most recently reported by the DfE is the widest on record since they first began collecting the data 16 years ago. This is true whether we look at access to HE in general, or access to more selective ‘high-tariff’ universities. The percentage point gap in participation by FSM status might not be the only barometer we are interested in, but the lack of progress on this metric (and only minimal progress on reducing gaps in participation between those from different neighbourhoods) sits somewhat awkwardly alongside over £200 million of annual expenditure on this issue.

The importance of evaluation

We should not necessarily infer from these statistics that WP outreach has been unsuccessful. Whilst the proliferation of WP outreach has not coincided with a narrowing of the FSM participation gap, we should bear in mind the possibility that the FSM gap might be even wider still today were it not for the influence of WP outreach. But the fact that we can’t answer this question adequately is a problem: we still don’t know anywhere near enough about whether this significant investment in outreach has been well spent, or whether it could have been more successfully deployed in other ways. How can we change this?

First, we need to significantly improve our efforts to evaluate WP outreach initiatives effectively. Often, we don’t really know what works, because of the lack of experimental or quasi-experimental design in the implementation of WP programmes. We won’t be able to make significant improvements to the evidence base until this happens.

Second, we need to ensure that WP outreach programmes are targeted effectively and are recruiting the right people to take part. Recent research has evaluated the ‘Realising Opportunities’ outreach programme, which focuses on supporting disadvantaged young people to progress to more selective research-intensive universities. Programme participants were found to be much more likely to progress to these research-intensive universities when compared to predictions made by statistical modelling which took into consideration participants’ prior attainment and personal characteristics. Part of the success of the programme hinged on the fact that most participants would be unlikely to progress to research-intensive interventions in the absence of the intervention, leaving a big margin for improvement.

In contrast, some other programmes may not be so well targeted. For example, recent evaluations by TASO of online and in-person ‘summer school’ outreach activities found that the programmes were unlikely to change participant behaviour given that most participants were already on a pathway to HE even prior to taking part in the interventions. If outreach is to be successful, it has to avoid merely preaching to the converted.

Finally, we can improve the evaluation of WP outreach by making greater use of the rich education administrative data that we are lucky to have access to in England. The Realising Opportunities research used linked National Pupil Database (NPD) and the Higher Education Statistics Agency (HESA) undergraduate record data, which remain underexploited in research in this area. The recent evaluation of Uni Connect mentioned above made use of the ‘HEAT’ (Higher Education Access Tracker) dataset which is a huge administrative record concerning participants in a large number of WP outreach programmes over many years. However, as this dataset was only available on its own, a comparison could only be made between those who had engaged more and less intensively with outreach programmes, with no comparison made with those who had not taken part in outreach at all.

If we can successfully link together datasets such as HEAT with the NPD and HESA records, we will have a more accurate view of the extent to which outreach participation makes a difference when all other observable characteristics of students are equal. If and when we are able to throw LEO earnings data into the mix too, we ought to be able to gauge the extent to which WP outreach programmes fulfil their ultimate purpose of supporting disadvantaged young people through the education system and into well paid careers. At this point we would have the clearest insight yet into which particular programmes offer the best return on investment.

Catch-22: we cannot have growth without a focus on education

By Blog editor, on 8 March 2024

By Professor Lindsey Macmillan and Professor Gill Wyness

We were having a discussion in our CEPEO team meeting yesterday about Spring Budget 2024 and the implications for education policy. As we outlined in our Twitter thread, there’s resounding disappointment across the education sector based on the announcements, with very little offered in terms of investment in education and skills. It’s no real surprise of course, given there is no money. Without any real prospect of economic growth this will be the story for the foreseeable future. And yet, and this is the catch-22 of it all, we cannot have growth without a focus on education and skills. In the words of John Maynard Keynes “We do nothing because we have not the money. But it is precisely because we do not do anything that we have not the money”.

Lip service is often paid to the importance of education and skills for growth, and we hear regularly about investments to support the development of skills in particular sectors – AI or green growth, for example. But while these skills are undoubtedly going to be important for future growth, it is the skills of the many, not the few, that are critical for productivity. And, as we know from a wealth of evidence about the effects of the pandemic, the challenge here is a daunting one. We can see from the most recent assessments at the end of primary school that the proportion of pupils reaching expected standards in reading, writing, and maths are down to 60%, levels not seen since 2016. In addition, inequalities have risen. The disadvantage gap is now higher than any point in the past decade.

As outlined in the Times Education Supplement piece this morning, there was a fully-costed education strategy put in place by Sir Kevan Collins, at the request of the government, in 2021 to help children who had missed school during the pandemic. This was based on the idea of three Ts. Teachers, Tutoring, and Time. Invest in the education workforce, invest in tutoring, and invest in extending the school day. Each one supported by rigorous evidence. And each one intertwined with the other to create complementarities to support education recovery. £15 billion was the ask, equivalent to £1,680 per pupil. This might sound like a lot of money but it was against a backdrop of estimates of the economic cost of learning loss reaching as high as £1.5 trillion, because of a lower-skilled workforce. In the end, only one tenth of this £15bn was offered up by the then Chancellor (and current PM), prompting Sir Kevan Collins’ resignation.

This is one example of the short-termism of government policy relating to growth: the reluctance to spend money now for the sake of future benefit. Those incomprehensibly large numbers of the economic costs of learning loss won’t fully hit now, but will instead permeate for decades to come. This means there is little incentive to spend the required money now; government won’t see the immediate benefits and get direct political gain in this election cycle.

Human Capital or Signalling?

A telling part of Sir Kevan Collins’ interview is that there was some kind of idea that the learning lost during the pandemic “would all just come out in the wash”. That children and young people who missed months of school would just catch up with little intervention required.

But this suggests that children can miraculously learn more in a year than they might otherwise have done with no further investment. That somehow teachers could be more productive after the pandemic than before – despite the myriad other challenges the pandemic created or worsened, not least significantly higher school absences. It also suggests that the government didn’t think that investment in the education system would have led to more learning.

But that goes against one of the fundamental theories of economics – human capital theory. The idea is that education increases the stock of human capital – skills – and higher skills fuel productivity and the economy, so investing in education is one of the most effective ways to drive sustainable economic growth. This is backed up by a wealth of evidence establishing a positive return to individuals and the wider economy from investing in education. Furthermore, education has been shown to have wider social benefits as more educated societies have higher levels of civic participation, better birth outcomes and reduced crime. We outline this in more detail in our briefing note “Does education raise people’s productivity or does it just signal their existing ability?”

There was also a lot of discussion at the time that learning loss didn’t matter anyway – because education is just there to act as a signal to employers about the relative abilities of different individuals, rather than something that directly improves their productivity. In other words, if someone has 3 A*s at A level, this tells an employer that they are a better worker than someone with 3 Bs, and it doesn’t matter how much knowledge or skills the person with 3 A*s actually has. But the evidence around this is much weaker as our briefing note describes.

Wasted talent

Linked to this is the belief that learning loss would be equally felt by all pupils. But again, the evidence (including from our own COSMO study) has shown the opposite. Learning loss is felt much more by pupils from disadvantaged backgrounds, and thus failing to invest in catch-up has compounded inequality. This inevitably results in wasted talent, further stifling economic growth, as outlined in our UKRI-funded project exploring the links between diversity, education and productivity. Evidence from the US shows that between 20-40% of economic growth over the last 50 years resulted from a better allocation of talent.

Failing to invest when pupils are young also has knock on effects. Education and skills are like building blocks. It is much easier to build an individuals’ skills if they have an existing foundation of basic skills to build upon. This in turn leads to higher returns on investment, as individuals become more and more skilled.

The catch-22 illusion?

This isn’t the first time education has been side-lined in recent budgets. Even the childcare announcement of 2023 was really about increasing labour force participation, rather than investing in early childhood education.

This short-term outlook is the government catch-22: we need growth to invest, but we can’t invest without growth. We need to break this cycle and understand that human capital is the fundamental underpinning of economic growth.

Exploring gaps in teacher judgements across different groups and the implications for HE admissions

By Blog Editor, on 31 January 2024

By Oliver Cassagneau-Francis

This blog was originally published on ADR UK (Administrative Data Research UK)’s website [link to original post].

In this blog post, CEPEO research fellow Oliver Cassagneau-Francis describes how he and the project team (CEPEO director Lindsey Macmillan, deputy director Gill Wyness and affiliate Richard Murphy) will use the Grading and Admissions Data for England dataset to study differences in predicted grades and compare the resulting outcomes for different groups of students. This project is funded through an ADR UK Fellowship.

Students from more advantaged backgrounds are three times more likely to go to university than their peers from less advantaged backgrounds, and they are also more likely to go to highly selective courses. These courses often lead to better careers. Recent work has shown that for students with the same level of academic attainment, the quality of the course they enrol into varies across socio-economic groups. In particular, students from more advantaged backgrounds enrol into more selective university courses than students from less advantaged backgrounds who achieve the same grades at school. This is true across the spectrum of student attainment.

A likely driver of these differences is the important role of teacher-predicted grades in UK university admissions. Students generally apply to university and accept their places before sitting their exams, relying on predictions of their grades made by their teachers (henceforth “predicted grades” or “predictions”). These are generally inaccurate.

Predicted grades became more complex during the pandemic

Unpacking UCAS predicted grades is a difficult task. Teachers are asked to be optimistic in their predictions, and so it is unclear whether achieved grades are the correct comparison for predicted grades. However, during the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020, exams were cancelled and teachers, having already given the predicted grades needed for university applications, were asked to now give their students grades that would become their actual A-level results. These were called centre-assessment grades. Note that with these grades, teachers were asked to provide a realistic judgement of the grade each student would have been most likely to get if they had taken their exam(s) in a a given subject and completed any non-exam assessment; so there is not the element of optimism that is in UCAS predictions.

Therefore, we have two groups of students with different information on each: a group who have predicted grades and actual grades (the pre 2020 cohort); and a group for whom we have predicted grades and centre-assessment grades (the 2020 cohort). By comparing UCAS predictions with centre-assessment grades and with actual grades we can learn about how teachers make predictions.

In addition, in 2020 teachers were asked to rank students within the centre-assessment grades, meaning it’s possible to see which students just achieved a given grade and which ones just missed out.

How administrative data can provide new insights

For this project, we will use this unique information to study how teacher predictions differ across different social groups (e.g. by socio-economic status, gender, or ethnicity). We will also study the impact of receiving different predictions – teacher-predicted grades for university applications, and centre assessed grades – on outcomes, such as which university and course students went on to enrol in.

To do this, we will use the Grading and Admissions Data for England (GRADE) dataset. This contains de-identified data on students from:

- the Office of Qualifications and Examinations Regulation (Ofqual)

- the Department for Education (DfE)

- the Universities and Colleges Admissions Service (UCAS).

The data from these different sources has been linked together, de-identified and made available to accredited researchers. The dataset is very comprehensive, covering nearly all students who were in school in England and took their GCSEs or A-levels in 2018, 2019 and the 2020 cohort whose exams were cancelled in summer 2020. This project will focus on the A-level students from these cohorts.

Measuring differences in teacher judgements across groups

In this project, we will study carefully those students placed either just above or just below a grade boundary in 2020, using centre-assessment grades and teacher rankings. If these look different – for example, if women (or students from ethnic minority or lower socioeconomic backgrounds) are more often found at the top rank of a B boundary, than at the bottom of an A boundary then this suggests bias against women (or students from ethnic minority or lower socioeconomic backgrounds) – this will suggest that teachers might be predicting more or less generous grades for students from different groups. We will expand this analysis to look at specific subjects (e.g. Maths and English) and specific grade boundaries (e.g. A* / A). We can also perform a similar exercise using exam grades and marks (pre-2020), allowing us to compare the distributions of students around grade boundaries that are determined by exam versus those due to teacher judgements. Ofqual carried out their own analysis of the centre-assessment grades, finding limited evidence that student characteristics influenced grades, and they release equalities analyses for each round of exams.

In the second part of the project, we will again look closely at students just on either side of a grade boundary and compare their university enrolments and other outcomes. These students are ranked very closely by their teachers but look quite different to universities, as they received different (centre-assessment grades. It will also be interesting to compare outcomes of students who were ranked very closely by teachers, who were given different predictions pre-Covid. By comparing their outcomes, we will be able to isolate the impact of receiving an A over a B (both at the predicted grade and at the actual grade level), for example, on students’ university pathways.

Teachers are one of the main drivers of student success at GCSEs and A levels, success which then goes on to determine future outcomes. Understanding whether there are discrepancies in teachers’ judgements in favour of certain groups over others, resulting in differences in school attainment and university choices, will help us to understand the implications for social mobility and equity.

Universities bank on foreign currency

By Blog editor, on 29 January 2024

by Professor Gill Wyness and Professor Lindsey Macmillan

This weekend, we woke up to the news that reporters from the Sunday Times had discovered that some of the UK’s top universities are allowing international students into degree programmes with lower grades than UK students.

While at first glance, this sounds grossly unfair and very much against CEPEO’s mantra of equalising opportunities, others have pointed out that this isn’t ‘news’: these are ‘foundation year’ programmes that are designed to help students with lower grades get access degrees by taking a year-long course to prepare them for entry.

While the details around this are still a little murky (why does the international agent in the Sunday Times video promise guaranteed entry to second year? And why do these programmes appear to have 100% conversion rates onto degree programmes?), it has brought the perilous state of UK university finances to the forefront.

At the heart of this issue is the UK universities’ reliance on tuition fees from international students to balance the books.

The majority of universities’ teaching resources come from tuition fees, though they also receive some teaching grant from the government. However, the tuition fee cap has been frozen (apart from a small increase of £250) since 2012. This means that in real terms, it has been cut by around a fifth over the last ten years. Recent IFS analysis showed that per-student resources for teaching home students have declined by 16% since 2012.

Against this backdrop, international students are very attractive to universities. Their fees are unregulated, and universities typically set them at much higher levels than those for domestic students, meaning they provide huge amounts of much-needed income, particularly in tough times.

Crowding out or crowding in?

While it has long been the case that universities have used money from international students to subsidise UK students, it is reasonable to be concerned that increasing reliance on international students may result in ‘crowding out’, where talented UK students are denied a place on a course because that place has gone to a more lucrative, foreign student. But there is little evidence of this.

Research by CEPEO affiliate Richard Murphy, alongside Steve Machin, studied this question for the UK system between 1994-2011, a time of rapid internationalisation of the UK HE sector. Their study found no evidence that UK undergraduates were crowded out by international students. They also found evidence that postgraduates (whose numbers – like undergraduates under today’s system – are unrestricted) were ‘crowded in’ by foreign students. In other words, their work showed that foreign students provide much needed subsidies to the UK sector, and that without them, even fewer places would be available to UK students.

The evidence from this year also shows little evidence of crowding out; an interrogation of UCAS data from 2023 reveals that of students (under age 21) applying to all UK universities, 354,450 were from England, 28,010 were from Scotland, 15,560 were from Wales, and 14,650 from Northern Ireland. This compares to 82,760 from non-EU countries, and a further 18,810 from the EU. Thus, students from abroad make up about one fifth of total numbers.

This proportion has remained constant since 2018 – while the share of non-EU students has risen from 11% to 16% over the period, the share of EU students has fallen from 8% to 4%. Thus, it seems that UK universities are simply replacing EU students (who, as a result of Brexit, have faced higher fees from 2021 and are no longer eligible for fee loans) with non-EU students.

Out of options?

While these numbers may provide some reassurance on the issue of UK students being frozen out of the sector, there is no doubt that more funding for domestic students is urgently needed – particularly given demand from UK students is likely to increase even further in the next few years due to increasing participation and the population surge currently working its way through the secondary education system.

Figure 1: Pupil numbers in education

Source: Figure 3.1b) from IFS Annual report on education spending

However, this is politically and economically very tricky. Raising the tuition fee cap would be deeply unpopular with the electorate, given the cost-of-living crisis. A recent report by Public First found that a sizeable portion of the population still support the idea of fee abolition, although this declines when the economics of paying for this are explained in more detail. But the vast majority of respondents were opposed to the idea of increasing tuition fees.

Figure 2: Polling on support for changes to tuition fees

Source: Public First report on Public Attitudes to tuition fees

The alternative – injecting cash into the sector through raising the government teaching grant – would be extremely expensive, so is also unlikely to fly at a time of significant fiscal constraints.

In short, there are very few options available to the government, meaning reliance on overseas students is set to continue for the foreseeable future.

Too Much, Too Little? Finding the ‘Goldilocks’ Level of Assessment to Advance Personalized Approaches to Education for Everyone

By Blog editor, on 24 October 2023

By Dr Dominic Kelly

This article was first published by UNESCO MGIEP as part of The Blue Dot 17: Reimagining Assessments.

I like to think my teachers would say I was a relatively good child, but I am not sure they would say I was the most consistent one. In school, concentration on my studies was too often distracted by Pokémon cards, Arsenal F.C., and elaborate daydreams. As inconsistent as I was, from my experience, I knew that some of my classmates could be even less consistent – how they behaved yesterday could be radically different to how they behaved today, regardless of how clever they could be at their best. Given the challenges that many children face at home, there were many reasons for these inconsistencies. Did they get a good night’s sleep, despite a noisy, overcrowded house (Hershner, 2020)? Did they even have breakfast that morning (Hoyland et al., 2009)? Therefore, if you had entered our classroom with a clipboard and a page of arithmetic on a random Wednesday afternoon, I am unsure that you would have caught all of us at our best – or even at our most typical. Likewise, whether our typical selves happened to be present on the same day as standardized tests were administered, was certainly not a given. Perhaps this all seems obvious to you but, despite this, why are single assessments of children often assumed to be representative or reliable?

In recent years, there have been understandable worries that we assess children too much (Hopkinson, 2022). Students and parents have reported that schools put too much focus on ‘high stakes’ testing, potentially to the detriment of children’s ‘love of learning’ (More Than a Score, 2020) and to their mental health (Newton, 2021) – although it should be noted that recent empirical research in a British sample found no relation between children’s wellbeing or happiness in school and participating in standardized testing (Jerrim, 2021). Either way, there is a distinct possibility that high- stakes standardized assessments are not the most representative way of assessing children’s educational capabilities (e.g., Morgan, 2016). Furthermore, I would also suggest that the most vulnerable children from the least consistent home settings are often those assessed the least fairly. Increasing evidence suggests that our cognitive performance in any given moment is affected by many contextual factors (e.g., Chaku et al., 2021). If so, given the variability that we know all children but especially the most disadvantaged show, conclusions about academic behaviours which are drawn from single measurements may not be as representative of a student’s capabilities as once thought because these measurements are affected by external factors such as sleep, stress or nutrition. Given this, there should be a real concern that single assessments, whether standardized or not, could be a format that works to the advantage of children from affluent backgrounds, while being particularly unfair to children from disadvantaged ones. For this reason, I would argue that education experts and developmental psychologists typically assess children too little. Instead of having occasional high-stakes assignments which potentially disrupt learning and increase tension in the classroom, I argue that there is a need for more frequent, low-stress assessments that occur in the background of the learning environment without disrupting instruction, which are not only more representative of achievement but also allow us to really engage with what makes a child’s classroom experience so variable from day to day.

Technological advances in educational technology (EdTech) offer us the potential to fundamentally change how interventions are developed for students, which can represent their variability in a manner which is much closer to “real time”, especially in high-income countries where many classrooms might have these technologies already available. Largely because of the substantial amount of labour and expenditure required to administer assessments, longitudinal educational studies have traditionally had long measurement intervals – for example, years or months apart. But what might appear to be relative stability in educational behaviours when assessed infrequently may in fact be a highly dynamic process with substantial fluctuations between days. Modern technology in the classroom setting provides the opportunity to dramatically reduce costs and both increase the number of assessments and decrease the intervals between assessments – for example, intervals of days, hours or even minutes. This latter approach to assessment can be considered prototypical of intensive longitudinal designs, which involve the collection of many repeated observations per person (also known as micro-longitudinal designs). Data for these studies are often collected by measuring individuals’ thoughts and behaviours, typically in familiar environments (e.g., the classroom, at home), instead of unfamiliar laboratory environments, with relatively non-intrusive smartphones, tablets, wearable technology, and so on. These assessments go beyond traditional continuous assessments as contextual, non-cognitive factors can be collected too. These studies may also be more accurate due to the decreased intervals between when thoughts and behaviours occurred and when they are reported (Trull & Ebner-Priemer, 2014).

One of the most important benefits of collecting intensive longitudinal data is the potential to adapt instruction to the needs and variability of each child. Instead of generalising broad conclusions across students, we have the potential to utilize previously unfathomable amounts of data collected from EdTech to create highly personalized models for every child. To date, intensive longitudinal studies have disproportionately featured adults (e.g., Kelly & Beltz, 2021) and have rarely been set in the classroom. Yet, compared to data collected much less frequently, intensively collected data on the variability of student’s’ experience can be sought regularly in the classroom – learning behaviours and outcomes, wellbeing, peer interactions, and so on. Personalized education is a burgeoning field focused on leveraging ‘big data’ to develop complex but parsimonious models based on students’ needs and nuances, which can lead to effective interventions, but there is still relatively little known about what factors in children’s daily lives are important for their academic achievement and wellbeing. Intensive longitudinal studies can inform this and facilitate potentially powerful personalized interventions. This personalization is particularly important given the diversity we see in the classroom. Many intervention efforts for equalizing educational outcomes have been designed for the ‘average student’. Yet, no student is average: students’ learning processes are contextualized by the intersections and interactions of each element of their identity, background, and history, which may not be consistent in how they manifest in the classroom every day. Rather than apply broad educational practices across students, leveraging intensive longitudinal data offers enormous potential for developing highly personalized models and interventions tailored to each student’s unique needs.

Given that personalized approaches to education require a greater number of assessments than other approaches, there is some concern that administering regular assessments could be burdensome for teachers and potentially disrupt learning. The innovative applications of EdTech, so that assessment goes relatively unnoticed while providing the most benefit, are therefore essential. Many classrooms in high-income countries already have some relevant technological infrastructure in place, even if it isn’t intended for that purpose yet. Daily educational data is already being collected: namely, formative assessments which are used at the moment by educational professionals to monitor progress. Although continuous forms of assessment can potentially be useful for reducing the pressure on students on specific occasions, their potential is being underutilized: these data also allow for a more fine-grained understanding of what predicts and what is predicted by students’ daily variability. The thoughtful measurement and modelling of this data could be elucidating, but there is still a lack of suitable methods, leaving the field “data rich but information poor”. If this data could be complemented by other short-form, easy-to-administer surveys about behaviour or cognition, it would be possible to address questions about children’s individual progress and setbacks in the classroom, without placing extra stress on teachers. To ensure this, thoughtful teacher training will need to be developed and provided, which itself will likely need to be tailored to teachers’ existing knowledge of EdTech. An important challenge will be determining the right number of assessments that provide enough fine-grained detail to understand the complexity of a child, but that is not so demanding that it impedes the classroom – in fact, that ’Goldilocks’ number of assessments may itself be unique to each child. Of course, there are continued inequities in access to these opportunities as it is mostly high-income economies that have embedded technology in their classrooms, and there are also notable differences in opportunities within those economies. As EdTech decreases in cost and hopefully spreads to more diverse settings, an important challenge will be designing and administering assessments which are culturally specific to local educational needs and resources.

Another potential limitation of intensive longitudinal designs is that they track fluctuations over short periods of time, but do not alone allow for plotting long-term changes. Therefore, there is a clear need for studies and interventions that combine both traditional and intensive longitudinal assessments together – what are called ‘burst designs’ (Stawski et al., 2015). For example, one could measure children’s academic performance and experience in the classroom every day for two weeks, every year for five years. Such a design would have the potential to address unique questions about how short-term fluctuations become long-term change. Are there specific times in a child’s life where they are the least consistent in their behaviours, and does that matter? Is a child’s lack of consistency in daily assessments indicative of problem behaviours in later life? Only by integrating intensive longitudinal data and traditional longitudinal data can these questions be addressed.

In sum, we have good reason to question whether single assessments can truly represent the variability of a child’s experiences in the classroom. Contextual factors can lead to substantial fluctuations in cognitive performance. Intensive longitudinal studies to measure these fluctuations have previously been used primarily with adults, but this work has generally not yet translated to the classroom or with children, despite the potential that the thoughtful leverage of this type of assessment offers for our understanding of variability and the future of personalized education. Furthermore, there is a distinct need for research that suitably assesses both short-term fluctuations and long-term change together, to determine how the former becomes the latter in ways that are potentially unique to each child. I believe this to be a worthy endeavour – individualized approaches to education which fully engage with the heterogeneity of the unique disparities that students face, have the potential to reduce barriers, equalize outcomes, and improve social mobility. The inconsistency of a child’s cognition or behaviours should not be treated as error, noise or inconvenience but as a vital, and long overlooked, aspect of their development.

I’d like to thank my doctoral dissertation committee – Drs. Adriene Beltz, Pam Davis-Kean, Robin Edelstein, and Ioulia Kovelman – for their insight in developing this line of research with me.

The Class of 2023: (some of) the kids are alright

By Blog editor, on 17 August 2023

By Gill Wyness, Lindsey Macmillan, and Jake Anders

Today marks the first ‘true’ A level and Vocational and Technical Qualifications (VTQs) exam results since the more innocent days of 2019. Although pupils sat exams in 2022, their results were adjusted by Ofqual’s “glide path” which aimed to move results gradually back to pre-pandemic exam grading following the grade inflation of 2020 and 2021. So, a comparison of todays’ results versus 2019 should provide information about the extent of learning loss experienced during the pandemic. And the results present a bleak picture for inequality in England.

Back to the future?

Overall, the proportion of pupils awarded a C or above at A level is more or less back to 2019 levels. This is perhaps grounds for optimism; these students have had a very different learning experience compared to their peers in 2019. They experienced a global pandemic, and severe disruption to their schooling in critical years – as Figure 1 shows. In addition, this cohort did not sit GCSE exams, so lack that crucial experience of performing under pressure that previous cohorts have had.

Figure 1: Timeline of the Class of 2023

However, there is much less cause for optimism when we look at inequalities in the results. At the moment, these are only available across school types, and regions.

Mind the gap

Looking first at inequalities by school type, the gap between academies and independent schools has widened since 2019. The proportion awarded a C or above is down slightly in academies (75.4% in 2023 versus 75.7% in 2019) whilst it is up in independent schools (89% versus 88%). This represents a 1.3 percentage point increase in the state-independent gap, which now stands at 13.6 percentage points. For the top grades (A and above), the independent-state gap has widened slightly more, to 1.4 percentage points.

We already know that students from these different school types had very different schooling and learning experiences during the pandemic. Figure 2, from CEPEO’s COSMO Study, highlights the disparity in learning provision experienced by students from different school types during the pandemic. The disparities in A level performance that we see today are yet more confirmation that these students did not experience the disruption of the pandemic equally.

Figure 2: Provision of live online lessons, by school characteristics, lockdown 1 and 3

There are also notable inequalities across region. In particular, (and as was the case last year), London and the South East continue to pull away from all other regions with the largest increase in the proportion achieving A/A* since 2019, and some of the smallest declines relative to last year’s cohort. Meanwhile, the North East and Yorkshire and Humber are the only regions with a lower proportion achieving A/A* compared to 2019.

Competitor advantage

As discussed, it is harder to make comparisons between today’s results and last years, because 2022 results were adjusted by Ofqual’s glide path. However, for pupils receiving their results today, the 2022 cohort are their closest competitors in terms of higher education (gap year students) and more crucially the labour market, so for them, the comparison really matters.

Overall, results are down from 2022; this isn’t surprising and is part of the glide-path strategy. However, inequalities here are concerning; for C or above, the academy-private gap is up 3.8 ppts compared to 2022.

Among the highest attainers (A/A*), the story is more nuanced. Compared to last year’s cohort the state-private gap has narrowed (1ppt). Remember private schools had far more grade inflation at the top of the distribution when exams were switched to Teacher Assessed Grades in 2021, as figure 3 clearly shows. That they have failed to maintain this stark advantage among top grades suggests some of the record grades awarded over the pandemic were likely down to teacher ‘optimism’. But as mentioned above, the gap among high attainers is up since 2019, therefore also reflecting the better quality of learning experienced by private school students during the lockdowns.

Figure 3: Teacher ‘optimism’ across school types

Subjective scrutiny

Comparing subjects that are more or less objective to assess can also tell us something about how meaningful the results of 2020 and 2021 might be. For example, if we compare results for maths – arguably an easier subject for teachers to grade in their assessments – with drama, we see just how problematic the teacher predicted/assessed grades of 2020 and 2021 were.

Figure 4: Grades by maths and drama

The forgotten 378,000

Of course today isn’t just about A levels – a sizeable proportion of the Class of 2023 – over 378,000 students – took Level 3 vocational and technical qualifications. There is far less data available on these qualifications to provide any real depth of analysis – an issue in itself.

Following a similar pattern to A levels, higher attainment grades for level 3 qualifications are: – up relative to 2019 (at distinction or above), and down relative to 2022 (at merit or above)

Many have pointed out the worrying dropout rates of those taking T levels (the new, technical-level qualification which were launched in 2020) – although it’s important to note that these currently make up only a tiny fraction of vocational and technical qualifications. Of those who did complete, 90% passed with girls outperforming boys at higher levels.

Inequalities persist

In summary then, today’s results present a mixed picture for young people in England. On the one hand, results are back to the pre-Covid heyday, but inequalities are wider, and this again emphasises the inequalities in experiences during the pandemic. These will likely persist well into the labour market – a feature that our COSMO study will track well into the future. Look out for more bleak news to come. This should be a timely reminder to those making education spending decisions in Whitehall for future cohorts.

Post-pandemic schooling challenges: CEPEO’s second annual lecture by Professor Joshua Goodman

By Blog Editor, on 10 August 2023

Lisa Belabed with Jake Anders and Lindsey Macmillan

Each year, CEPEO holds an annual lecture showcasing vital research on education policy and equalising opportunities. For this year’s lecture (held at Central Hall Westminster on Thursday 20 July 2023) we were delighted that Professor Joshua Goodman from Boston University, who recently completed a year in Washington DC on the US President’s Council of Economic Advisors, joined us to talk about his ongoing research on post-pandemic schooling challenges in the United States — which have many parallels with the challenges we are facing in the UK.

Professor Lindsey Macmillan, CEPEO’s Director, began proceedings by recapping highlights from the centre’s past year, including the recently released evidence-based policy priorities, and new research from the COSMO study, as well as reminding us that CEPEO was established just six months before the pandemic started, with its huge implications for educational inequalities and, hence, the direction of our research, including a shift to carry out work to understand post-pandemic schooling challenges.

How it Started

Professor Goodman’s talk was divided into three parts. He started with his research at the beginning of the pandemic, as 50 million children across the US saw their schools close their doors, for what would turn out to be periods ranging from a few months to over a year. At this point, there was virtually no data on school disruption of this scale, and this lack of historical precedent made it difficult to predict learning losses.

However, those unprecedented learning losses were difficult both to grasp and fully anticipate, and there were disparities among parents’ ability to and proactivity in responding to them. Professor Goodman and colleagues used Google Trends to try to quantify the extent of these responses: by April 2020 searches for school- and parent-centred online learning resources doubled compared to pre-Covid levels. Partly because of these differential responses, learning losses were worse for students in high-poverty schools, whose families were less likely to have the resources to compensate for their losses outside of school. Josh pointed out his own ability as a professor and former mathematics public school teacher in helping his children stay on track as exemplifying those disparities.

Beyond learning loss, Professor Goodman highlighted that school enrolment has also been adversely affected by the pandemic, with public school enrolment dropping 3% in autumn 2020, the largest decrease since World War II. Part of this can be explained by an increase in homeschooling, likely driven by health fears, but many of those students effectively vanished.

Josh was also keen to avoid being entirely negative in his assessment of the situation. One silver lining of the pandemic relates to bullying. Turning again to Google Trends data, Goodman and colleagues found that searches about bullying and cyberbullying (perhaps especially surprising for the latter) were reduced as a result of school closures. Suicide rates among children also decreased as schools closed.

How it’s Going

Having described the immediate impacts of COVID-19 disruption, Professor Goodman turned to post-pandemic recovery efforts. Early in the pandemic, the US federal government sent $60 billion to K-12 schools: an unprecedented use of federal funds for school support, as schools in the US are mostly funded at the state- or local-level. This was followed in March 2021 by Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief (ESSER), another $120 billion to be spent by 2024. A minimum of just 20% of ESSER was allocated to be spent on programmes to reduce learning loss, and a lot has rather been spent on temporary hires and salary increases for teachers. The extent of this support dwarfs that which we have seen in England, but appears to have been less well targeted.

As our understanding of the effects of the pandemic on learning loss has become clearer, the picture has remained bleak. The US has seen a drop in 8th grade math scores estimated to lower lifetime income by 1.6% or $1 trillion across all affected students. Chronic absenteeism rates have doubled in many states — more so in schools with high proportions of ethnic minority students — with an average of 6-7 missed days per school year. And enrolment has remained an issue: there was no rebound in enrolment in autumn 2021 to offset the 3% of students who had left public schools at the onset of the pandemic in 2020. While there were widespread concerns about teacher burnout early in the pandemic, there is a lack of direct evidence on this point, but the rate of quitting has jumped 17%.

What now?

Concluding his talk, Professor Goodman was keen to focus on the future and what we should be doing to mitigate the challenges he outlined. Asking “what now?” he set out what he sees as the biggest challenges facing education policymakers at this moment. First, the big federal spending in light of the still terrible learning results is leading to a narrative of wasted funds, which makes it challenging to obtain further funding. But, he pointed out, this ignores the counterfactual: the learning losses without this federal support could very easily have been even worse.

Second, districts (somewhat equivalent to English local authorities, albeit retaining more oversight over schools than many now have here) still do not understand the scope of intervention necessary to tackle the learning loss that has become embedded. On top of this, they are concerned that adding instructional time is not popular, are finding high-quality tutoring hard to scale, and that the teacher workforce is tired, sapping energy for taking the urgent action still needed.

Third, there is a perception that parents do not have the appetite to tackle the embedded learning loss their children are facing. This is largely because they often do not recognise that their child’s academic skills were affected by the disruption of the pandemic, as school grades (“on a curve”) can have tended to obscure learning losses from them.

In the face of these challenges, Professor Goodman stressed the importance of getting attendance back to pre-pandemic levels, as absenteeism makes all other interventions less effective. This mirrors one of CEPEO’s policy priorities of reducing pupil absenteeism. He also highlighted the need to help districts (or, in a UK context, school and academy chain leadership) understand the scope of intervention needed, as well as the importance of choosing solutions that scale. For instance, tutoring has proven difficult and labour-intensive, and Josh argues that other, more widely manageable, teaching solutions would be preferable, notably through technology that supports, rather than replaces, teachers’ work.

Wrapping up

The lecture ended with Professor Goodman reasserting the importance of data, which is foundational in his research on education and economics — the same being true for CEPEO. In the US, the local nature of schooling presents major data challenges. He also stressed the need for timely datasets: federal enrolment data is released with a one-year lag, which he argues is much too long: by the time the data are released, another school year has already begun so policymakers often feel that priorities have ‘moved on’. He also stressed a lack of data on important issues such as teacher workforce, and the difficulty of measuring ESSER funds’ spending and efficiency.

Having had the opportunity to speak with members of CEPEO on their own research, Professor Goodman referred to the datasets being used and developed within the centre. These include pioneering use of administrative data such as the Longitudinal Educational Outcomes (LEO) dataset, in partnership with the UK Government, along with the COVID Social Mobility & Opportunities (COSMO) study supported by UKRI Economic and Social Research Council and in partnership with the UK Department for Education. He called for more partnerships of this kind in building datasets that will allow research that drives forward education policy by helping to identify schooling challenges rapidly and responding to them just as rapidly.

Retain external examination as the primary means of assessment

By Blog editor, on 22 June 2023

By Dr Dominic P. Kelly

Earlier this year, CEPEO launched ‘New Opportunities’, a list of practical priorities for future governments based on the best existing evidence across the social sciences. One of our recommendations regarded calls to abolish high stakes educational assessment by traditional means (i.e., ‘high stakes’ external examinations). Although these calls are not novel, in the wake of disruption to traditional GCSE and A-Level examinations in the past few years, those calls have certainly grown recently. Critics of external examinations argue that they are merely a test of rote memory of impractical knowledge and neither measure the underlying skill they claim to nor improve a child’s educational experiences or later outcomes. There is additional suggestion that these exams lack predictive value for future educational achievement, particularly in higher education, and provide additional stress for students. Based on the existing empirical evidence, we disagree with these assertions. On this basis, our recommendation is to retain external examination as the primary means of assessment and contend that not doing so would harm equity between students in a way that outweighs other concerns around external assessment. Yet, we also advocate for evidence-based improvements to assessments to be made with the intention of holistically improving both the examination system and national curricula and we detail some potential changes below.

External examinations are more resilient to examiners’ bias

One primary concern about external examinations is that they are disadvantageous for students from minority groups compared to coursework or continuous assessment. Although continued effort is needed to modernise the curriculum and provide content and skills that are relevant to diverse backgrounds, the evidence that alternatives reduce disadvantage for minority groups is lacking. It is often suggested that internal assessments by teachers would be an optimal alternative. But evidence suggests that teachers are prone to either showing bias or being inaccurate in their assessments of students from minority groups. Research has shown that some teachers demonstrably show ethnic bias in their assessments such that nearly three times as many Black Caribbean pupils received predicted scores below their actual scores than White students. Additional research also suggests that students from higher socioeconomic status (SES) are more likely to have more favourable internal assessments by teachers than those students from lower SES backgrounds. Although it is sometimes thought that students from low SES backgrounds do comparatively better in coursework than examinations, evidence from the UK suggests that this is not the case. In addition, concerns about examinations causing increasing in student anxiety are contested: although test anxiety is a notable phenomenon among students, it has been suggested that there is minimal effects of test anxiety on performance in GCSE examinations and that children’s wellbeing or happiness was not related to their participation in Key Stage 2 external examinations. Therefore, systems without anonymous external assessments are thought to have substantial biases and this would have deleterious effects for reducing inequalities in the UK education system.

External examinations can be complemented by improvements made elsewhere

Despite our recommendation that external assessments remain the primary means of assessment, that is not to say that these assessments could not be complemented by evidence-based approaches to reform to the current curricula and assessment. First, concerns over the practice of ‘teaching to the test’ could be addressed by changing the content of the external examinations to reward a richer approach to teaching, which would likely benefit students. For example, providing examples with “higher level” items in classroom assessments (which encourage deeper processing of information than items that only require rote learning) may yield comparatively stronger performance on both low- and high-level items in external examinations. Incidentally, reducing the amount of time teachers spend on providing their own assessments of students could potentially provide more time for other activities in the classroom. Second, portfolios and other types of summative assessments can have utility as a complement to traditional exams but they should be marked externally by someone unfamiliar with the student to avoid biases. Third, and most of all, the administration of thoughtful formative assessment has the potential to prepare students for external examinations and potentially providing a greater context for external examinations to be interpreted within. Formative assessment has been shown to have notable positive effects on pupil attainment and can be structured in a way devoid of teacher bias. Given the evidence that single assessments of cognition can be affected by stress, sleep and other extraneous factors, there are benefits to repeatedly assessing smaller and more specific elements of knowledge or cognition in a way that complement single external assessments and benefit learning environments – as long as it can be done objectively and with minimal bias from educators.

Summary

We advocate for external assessments to continue to be the primary means of educational assessment in the UK. Switching to internal teacher-based assessment would set back attempts to reduce inequalities in the UK education system. Furthermore, we would argue that concerns about stress are surpassed by evidence of teacher bias and inaccuracies in internal assessments. There are additional benefits to students and teachers of summative or continuous formative assessment, but these are complements rather than substitutes for external examination. The content and format of external assessments, whether high-stakes or continuous, should continue to be re-evaluated in line with well-founded and methodologically rigorous research.

Reduced engagement in extra-curricular activities post-pandemic: should we be worried?

By Blog Editor, on 19 June 2023

COSMO researcher, Alice De Gennaro, considers the potential impacts of the dip in young people’s engagement with extra-curricular activities post-pandemic.

In our previous analysis, we documented the significant changes in extra-curricular activities that occurred during the COVID-19 pandemic. We found that students from less advantaged socio-economic backgrounds re-engaged with extra-curricular activities to a much lesser degree, especially when looking at school type. Females were also less likely to re-engage with these activities and we look at the implications of this.

We also consider what might be the implications of such changes. In doing so we describe the association between continuing engagement in extra-curricular activities and young people’s health and wellbeing. We build on the analysis in the previous analysis and in our measure of continuing engagement we include those who never did any extra-curricular activities pre-pandemic to get a sense of a more general notion of extra-curricular engagement. A summary of this measure is illustrated below.

Figure 1. Continuing engagement (N=6,286)

We find that higher rates of continuing with extra-curricular activities and engaging with these activities at all are associated with lower rates of high psychological distress, better self-esteem and more physical activity. Higher frequency of physical activity is associated with better self-esteem and lower rates of high psychological distress, although only up to a threshold of five days exercise per week. We also look at associations of these findings with gender, to see how effects of reduced engagement may be distributed.

It should be noted that analysis here is descriptive and causality cannot be inferred for a number of reasons including bi-directional relationships (those with worse health/wellbeing are more likely to disengage from extra-curricular activities, as well as reduced extra-curricular engagement potentially being a risk factor for worse health/wellbeing) and the likely presence of other factors driving both more extra-curricular engagement and better health and wellbeing.

How is continuing extra-curricular engagement related to health and wellbeing?

To form a picture of the relationship between extracurricular engagement and health and wellbeing, we analyse several relevant measures of health and wellbeing: GHQ-12 scores, self-esteem scores, and levels of physical activity.

Evidence has shown links between extra-curricular activities and benefits for mental health. Another study found similar associations also during the COVID-19 pandemic. The figure below echoes these findings as rates of high psychological distress are higher among those who never did or stopped all activity. The proportion in the latter group was higher, which is suggestive that the association between engagement and mental health is amplified when people stop an activity, as opposed to never having done it. Rates of high psychological distress were lower among the respondents who started and continued with extracurricular activities, with proportions being only marginally different between those continuing with one to two activities and those who continued with three or more.

Figure 2. Continuing engagement in extra-curricular activities and GHQ-12 score (N=5,933)

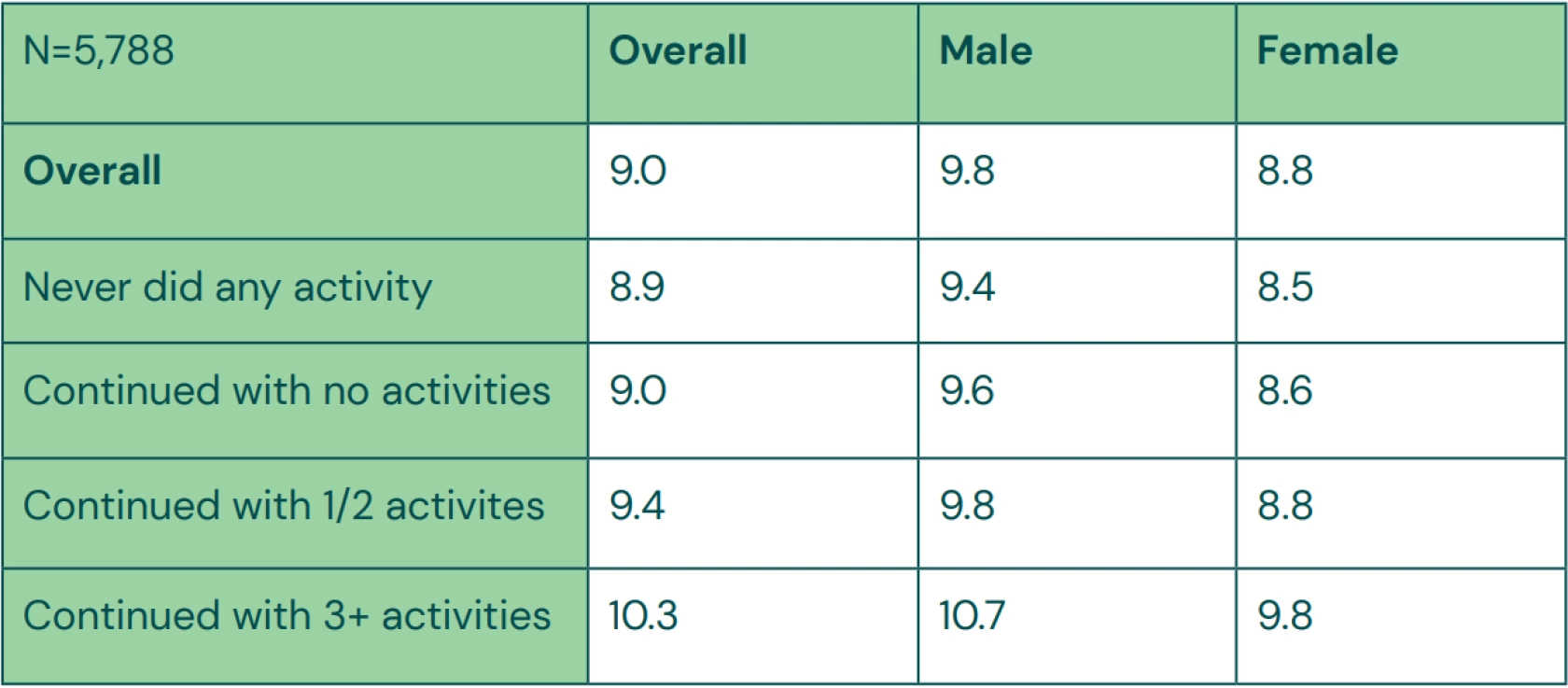

While the GHQ-12 measure attempts to capture a general picture of mental health, here we can pull out a specific relationship with self-esteem that engagement seems beneficial. Evidence suggests that extra-curricular participation is linked to self-esteem. Following this, we look at the responses to an adapted Rosenberg self-esteem scale ranging from 0-15, 0 being low self-esteem and 15 being high. The average across the whole sample is 9.27 (N=11,464). The average scores among those who never did any activity and those who continued with no activities are similar at just under 9. The score then increases by almost half a point for those continuing with 1-2 activities and then by a full point for those continuing with 3 or more.

Given the lower extra-curricular engagement of girls it is useful to look further into self-esteem by gender. Overall, we find that boys had an average reported self-esteem score of 9.8. The average for girls was lower, at 8.8, and lower still for non-binary+ individuals at 6.5 (N=11,464). The table below splits these scores out by our continuing engagement variable, and we see the same pattern persist, with scores rising with engagement but with girls reporting lower self-esteem at each level. This is consistent with common findings that girls report lower self-esteem than boys. The findings below may be cause for concern that the reduction in extra-curricular engagement following the pandemic could harm young people’s self-esteem and perhaps more disproportionately that of girls.

Previous analysis found that females in this cohort had higher levels of high psychological distress and so considering this alongside the findings about self-esteem might cause further concern about the different engagement patterns by gender.

Table 1. Average self-esteem scores by continuing engagement and gender (N=5,788)

How much of a role does physical activity play in extracurricular engagement and wellbeing?

One way to look into students’ extra-curricular life, aside from their participation in specific clubs and activities, is to look at their self-reported days of exercise per week. This allows us to focus in on the fitness aspects of their life outside of school. While the pattern between extra-curricular activity and general health is nonlinear, looking at days of exercise can tease out a more specific form of health and its relation to extra-curricular activity.

We found a significant association between students’ weekly physical activity and their continuation in extra-curricular activities, as shown in Table 2. The more students engaged with extra-curricular activities, the more exercise they did per week, with those carrying on with three or more activities doing twice as much weekly exercise as those who never took part in extra-curricular activities. This suggests (as we might have expected) that extra-curricular activities are a major source of physical activity. Looked at from a slightly different perspective, among those who reported zero days of physical activity per week, over a third didn’t continue with any extra-curricular activities. This proportion was half as much for those who exercised every day of the week, affirming that reduced engagement in extra-curricular activities was quite a hit to the physical activity of students.

Table 2. Continuing engagement in extra-curricular activities and days exercise per week (N=3,742)

We find a U-shaped relationship between number of days exercise per week and elevated risk of psychological distress. The greater the number of days of exercise per week up to five days is associated with a lower proportion at elevated risk of psychological distress. However, rates of poor mental health then increase slightly as days of exercise per week increase further from five to seven days, although the proportion at risk is still far lower than those doing no exercise in a week. This inversion at the highest levels of physical activity might be capturing an externalising response to stress, where young people are exercising more to alleviate higher levels of stress. Alternatively, it could reflect some form of burden of exercising nearly every day while handling other aspects of their life, such as schoolwork and other responsibilities.

Figure 3. Weekly physical activity and % at elevated risk of psychological distress (based on GHQ-12 score) (N=7,319)

Physical activity may be a component in the link between extra-curricular activity and self-esteem. Reported self-esteem scores on average increase by around one point when students move from zero days (7.8) to one day (8.8) of exercise per week. Students who exercised for two or more days a week had higher self-esteem scores ranging from 9.2-9.9. A similar pattern persists among boys and girls, although girls start from a lower score. While these changes are small, they are not insignificant.

Given that extra-curricular engagement appears to be a major source of physical activity, the link between self-esteem and extra-curricular activities may be driven by the apparent boost to self-esteem that higher levels of exercise are associated with.

Conclusions

In this blog post, we have tried to unpack the relationship between extra-curricular engagement and pupil health and wellbeing. By looking across a variety of measures we can draw some conclusions. There is a small but significant association of extra-curricular engagement with lower levels of high psychological distress and higher self-esteem. We should not ignore gender differences here, as females not only had lower levels of engagement but reported lower self-esteem scores overall.

Looking further into physical activity, it appears that extra-curricular engagement accounts for a large amount of the exercise students do per week, suggesting that the decline in engagement during the pandemic would have made exercise frequency lower. More frequent physical activity is also associated with lower rates of high psychological distress up to a point, along with slightly higher self-esteem.

The findings in this analysis suggest that we should not underestimate the impact of a decline in extra-curricular engagement. We should consider not just how this engagement affects labour market potential but the personal aspects for young people, such as their mental health, self-esteem and physical fitness, especially bearing in mind the different patterns for boys and girls. Because pupils from more disadvantaged backgrounds engaged less with extra-curricular activities following the pandemic, we must acknowledge that any implications of reduced engagement on health and wellbeing will likely disproportionately affect these groups. We need to address the barriers that young people face to taking part in extra-curricular activities in relation to their socio-economic background and gender, so that we can keep young people feeling positive and healthy.

This is the second piece in a two-part analysis.

Close

Close