Egyptian Languages: Explained

By tcrnlmb, on 23 January 2018

In our collection, we have representations of texts in all the major Egyptian languages.

What, more than one? Yes! From ancient Egypt to historical Egypt to modern Egypt, there were many different scripts and languages used…

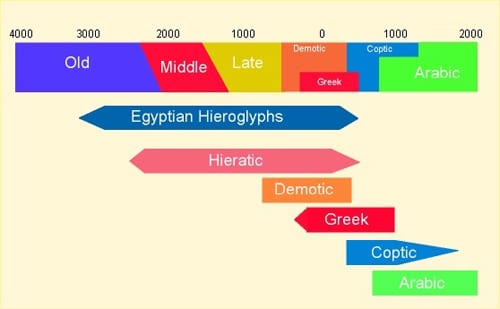

Hieroglyphs:

The script that is most recognisably Ancient Egyptian®. One of the oldest scripts used by the ancient Egyptians – and the script with the most longevity – its origins can be seen very early on in Egypt’s history, starting out life as single or small groups of signs that represented entire concepts or specific sounds. Already in the Early Dynastic Period (3100-2686BC), these signs were beginning to become standardised and by the 3rd Dynasty (2686-2613BC) were used in a wide range of contexts. They were, however, especially associated with religious texts, as it was believed that the beauty and monumental nature of hieroglyphs indicated that they were the ‘words of the gods’ (medu-netjer) and intended to be read by them.

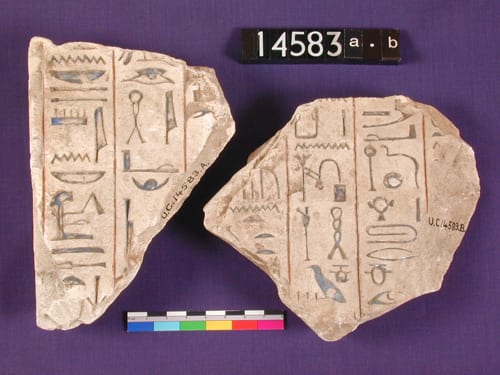

Hieratic:

As you can imagine, hieroglyphs take a lot of skill and time to write nicely. It is no wonder then that soon after the standardisation of hieroglyphs someone realised that for everyday purposes; ain’t nobody got time for that. This abbreviated and simplified version, a shorthand cursive of hieroglyphs, is called hieratic and was a script in the same language that could be used more fluently and written quickly. It was used by officials, scribes and also varying members of the general public (though all at different fluencies). If you are especially keen and the handwriting is neat, you will be able to discern how an hieratic character corresponds to its hieroglyph counterpart.

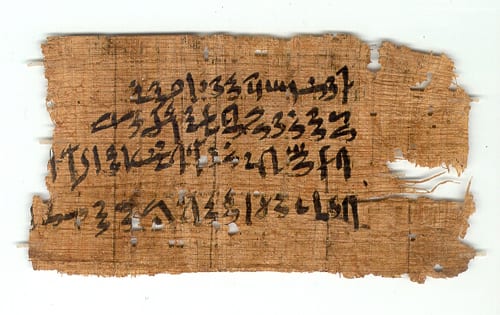

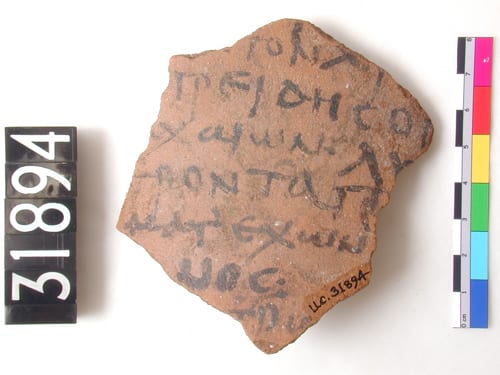

Demotic:

Demotic was developed in the north of Egypt, but did not gain widespread use in Egypt until after the conquest of Upper Egypt by Psamtek I in the 7th century BC. Derived from hieratic, it still represented the same language and kept the standardised writing structures, but it changed a couple of the phonetic pronunciations and became even more cursive. Demotic was primarily used administratively for the first couple of centuries, but was also used for personal affects and funerary items, such as the mummy label above, which would have been used to identify the person it belonged to after mummification. This script was used officially for over 300 years before the arrival of the new kid on the block…

Greek:

Greek, as a text, is present in Egypt earlier than you may think: in the 7th century BC, the Greeks settled in the Nile Delta and founded Naukratis, a colony-city that became the gateway between Egypt and Europe. However, it only becomes widespread after the conquest of Egypt by Alexander the Great and the appointment of the Ptolemy I as governor of Egypt in 323BC. After Alexander’s death and subsequent attacks from other interested parties, Ptolemy declared himself pharaoh in 305BC, which meant that Greek became very fashionable and the language of the elite.

However, as can be seen by the most famous example of a multi-lingual text, the Rosetta Stone, Egyptians at this time were speaking in a multitude of languages and writing in many scripts.

Interesting fact: quite a few of our Greek papyri have been extracted from cartonnage, a sort of paper mâché that the ancient Egyptians used to create face masks and foot casings for their burials.

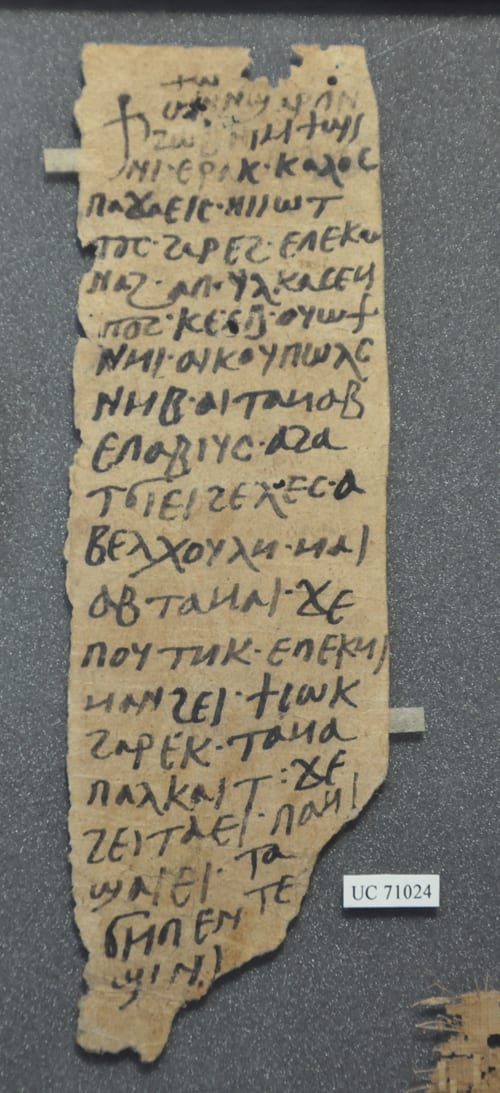

Coptic:

This is where it gets a little more complicated. When Christianity came to Egypt in the early first century AD, the primary language used in the church at that time, was Greek. Over time and as Christianity spread across Egypt, the Egyptian language evolved into Coptic, which was still the original Egyptian language, but used the Greek script with a few additions taken from demotic to represent sounds that the Greek language simply does not have.

Our collection reflects this history, as most of our Coptic texts are religious texts or were written by ecclesiastical persons.

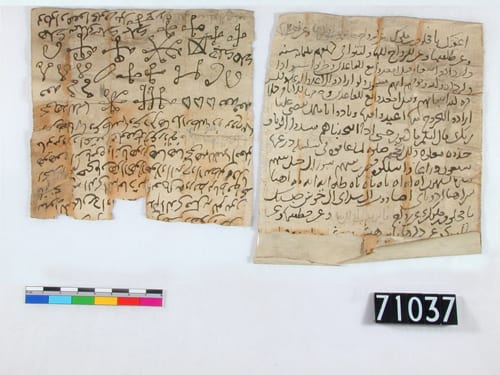

Arabic:

After Egypt was invaded and conquered by the Islamic Empire in the 7th century AD, Arabic became the main and official language in Egypt; as it still is today. Though, much like modern English has greatly changed since the 1500s, so too has Arabic in Egypt over the last 1300 years! It is also worth bearing in mind that Coptic was continuously used in contexts involving Christianity in Egypt and is even today the official liturgical language of the Coptic Orthodox church.

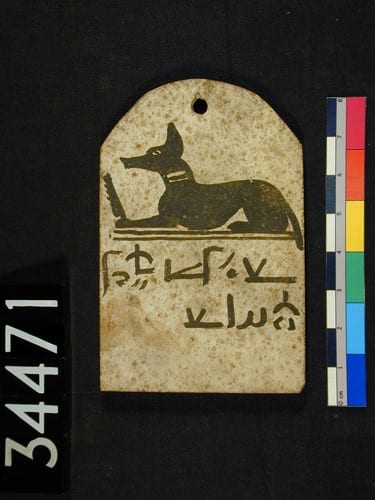

To show how these successive phases of scripts developed in Egypt from 4000BC to the present I found this diagram to be particularly helpful!

Language Timeline, Digital Egypt

So, three languages and six scripts later, I hope that this blog has helped illuminate the linguistic puzzle of ancient Egypt.

(Other languages also seen in Egypt, and in our collection to a much lesser extent, include: Aramaic, Latin and the scripts of foreigners living in Egypt, such as Cuneiform, Hebrew and Carian. To find out more about these scripts, the different languages of Egypt and about ancient Egypt in general, please visit the UCL Digital Egypt page.)

The Designation Scheme recognises, celebrates and champions significant collections of national and international importance held outside national museums. Awards of Designated status are made by an independent expert panel, based on the collection’s quality and significance.

The 2016-18 round of the Designation Development Fund is investing £1,330,849 to support projects that ensure the long-term sustainability of Designated museum collections.

The Designation Development Fund recognises the importance of excellent collections and provides funding for projects that ensure their long-term sustainability, maximise their public value and encourage the sharing of best practice across the sector. In this round, we will focus on opportunities around research and understanding of Designated collections.

***Arts Council England champions, develops and invests in artistic and cultural experiences that enrich people’s lives. We support a range of activities across the arts, museums and libraries – from theatre to digital art, reading to dance, music to literature, and crafts to collections. Great art and culture inspires us, brings us together and teaches us about ourselves and the world around us. In short, it makes life better. Between 2015 and 2018, we plan to invest £1.1 billion of public money from government and an estimated £700 million from the National Lottery to help create these experiences for as many people as possible across the country. http://www.artscouncil.org.uk/

Louise Bascombe is the Curatorial Assistant working on the Papyrus for the People Project at the Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology.

One Response to “Egyptian Languages: Explained”

- 1

Close

Close

Fascinating article!