Marks & Spencer (Pantheon store), 169–173 Oxford Street

By the Survey of London, on 17 May 2019

The site of the celebrated Pantheon (1772–1937), fronting Oxford Street and carrying through to Poland Street at the side and Great Marlborough Street at the back, is occupied today by the best-known London outlet of the Marks & Spencer chain, familiar for its distinctive polished black-granite frontispiece. The Pantheon was a place of public entertainment (originally with a spectacular domed interior) from its opening in 1772 to 1814, and afterwards the site of a bazaar and W. & A. Gilbey, wine and spirit merchants. The site was sold to Marks & Spencer Ltd in 1937. The store was constructed in 1938 by Bovis Ltd to designs prepared by W. A. Lewis & Partners in collaboration with Robert Lutyens (the son of Edwin Lutyens). It originally covered just the Oxford Street frontage of the Pantheon site, numbered 173 after 1880, together with the premises behind, but was extended eastwards in 1962–3 to take in the sites of Nos 169–171.

The front of the Pantheon branch in 2018 (© Historic England, Chris Redgrave)

Marks & Spencer Ltd opened their first West End branch at Orchard House, 454–464 Oxford Street near Marble Arch, in 1930. The decision to establish a larger store in the West End confirmed the success of the earlier enterprise and the energetic pace of the firm’s expansion. In 1916, Simon Marks took the helm of the company co-founded by his father and set about improving the business to fend off competitors such as Woolworth. Marks travelled to the United States in 1924 to study retail practices in chain stores, and returned with an insight into ‘the value of more imposing, commodious premises’, modernised administration and counter footage. [1] The public flotation of the company in 1926 generated funds for the construction of new stores. By the beginning of the Second World War, the company had built or rebuilt 218 shops and extended approximately 200 more. The Pantheon store was set apart from its contemporaries by its size, sophistication and superior location. One of its architects later recalled that it was ‘the store to outstore all stores, and the amounts involved in the acquisition of the site and the building were, by comparison with the stores which had already been erected, quite astronomical’. [2]

The task of designing this prominent store was entrusted to Lewis & Partners (later Lewis & Hickey), the architectural firm largely responsible for work in the south of England for Marks & Spencer. The building process was overseen by Ernest E. Shrewsbury, the head of its building department. Lewis & Partners also worked in collaboration with Robert Lutyens, who was appointed consultant architect to the company in 1934. He devised a standardised system for the street elevations of stores, which were faced with square artificial-stone tiles based on a ten-inch module to ensure uniformity and coherence. This inventive approach was applied to frontages of any size, including extensions. The application of polished black granite to the Pantheon and Leeds stores signalled their prestige and imitated the glamour of West End blocks such as the National Radiator Building (Ideal House) in Great Marlborough Street, Drages in Oxford Street, and the Odeon Cinema in Leicester Square. [3]

The Pantheon store, photographed in 1938 (The M&S Company Archive, P2/87/195)

The original store occupied the full site of the former Pantheon, reaching south to Great Marlborough Street and east to Poland Street. Lewis & Partners had produced plans for a three-storey north range fronting Oxford Street in 1936, but these were supplanted by a more ambitious scheme with a showy arcade. A four-storey block faced with shiny black granite was devised for the north front. The sleek façade was composed of five bays, with square first-floor windows set among chequer-work panels and three embrasures above containing tall Crittall windows and flat paterae. A plain parapet contained green neon lettering. The ground floor incorporated an arcaded shopfront executed by Holttum & Green of Holloway. This was lined with Bianca del Mare marble and furnished with gilded bronze display cases, including a central freestanding showcase. Two-storey ranges facing Great Marlborough Street and Poland Street were more modest in scale and quality of materials, being faced with glazed terracotta tiles. The east frontage initially comprised 39 and 41 Poland Street, its regularity interrupted by a pre-existing front at No. 40. The remainder of the site was occupied by a single-storey range which provided nearly 22,000 square feet of retail space. [4]

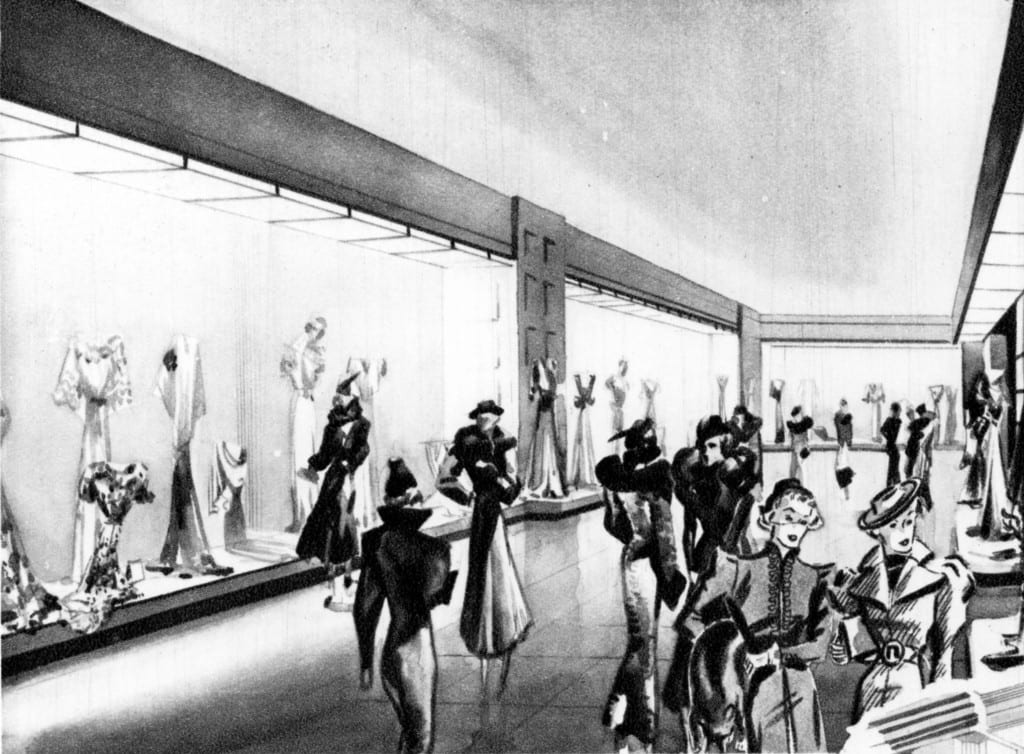

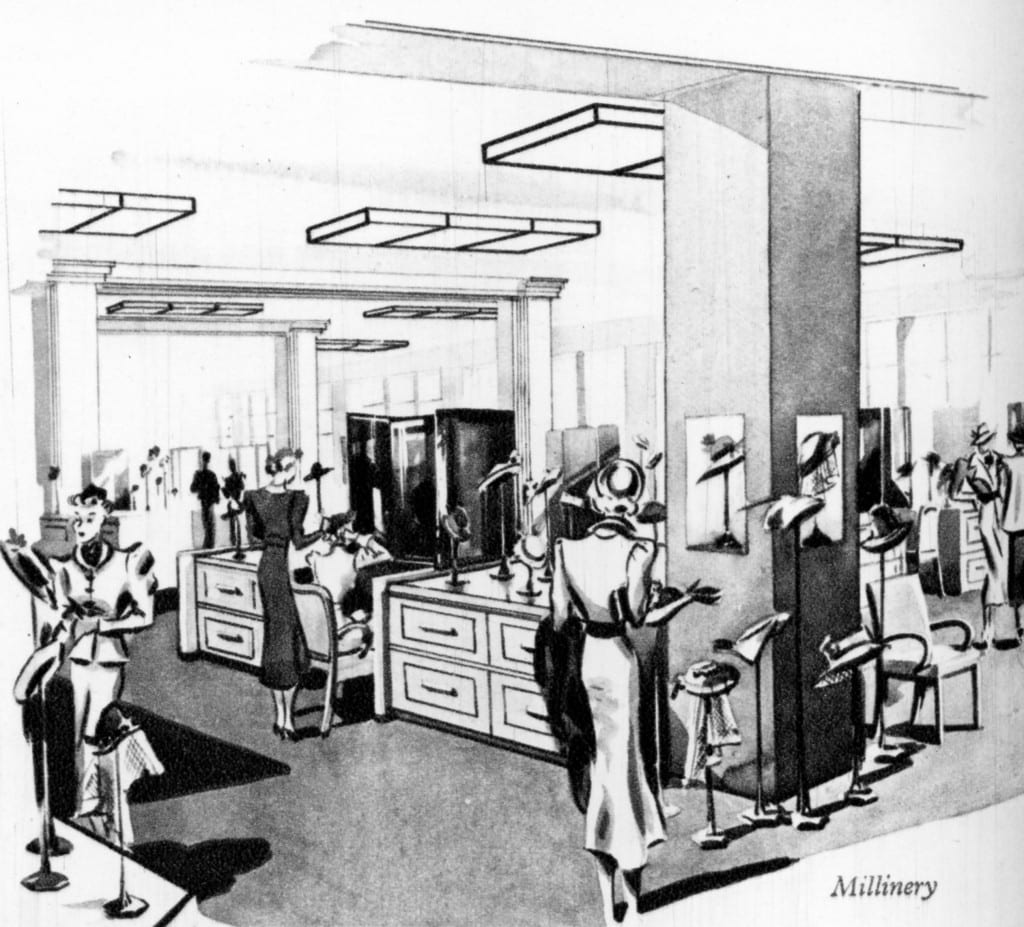

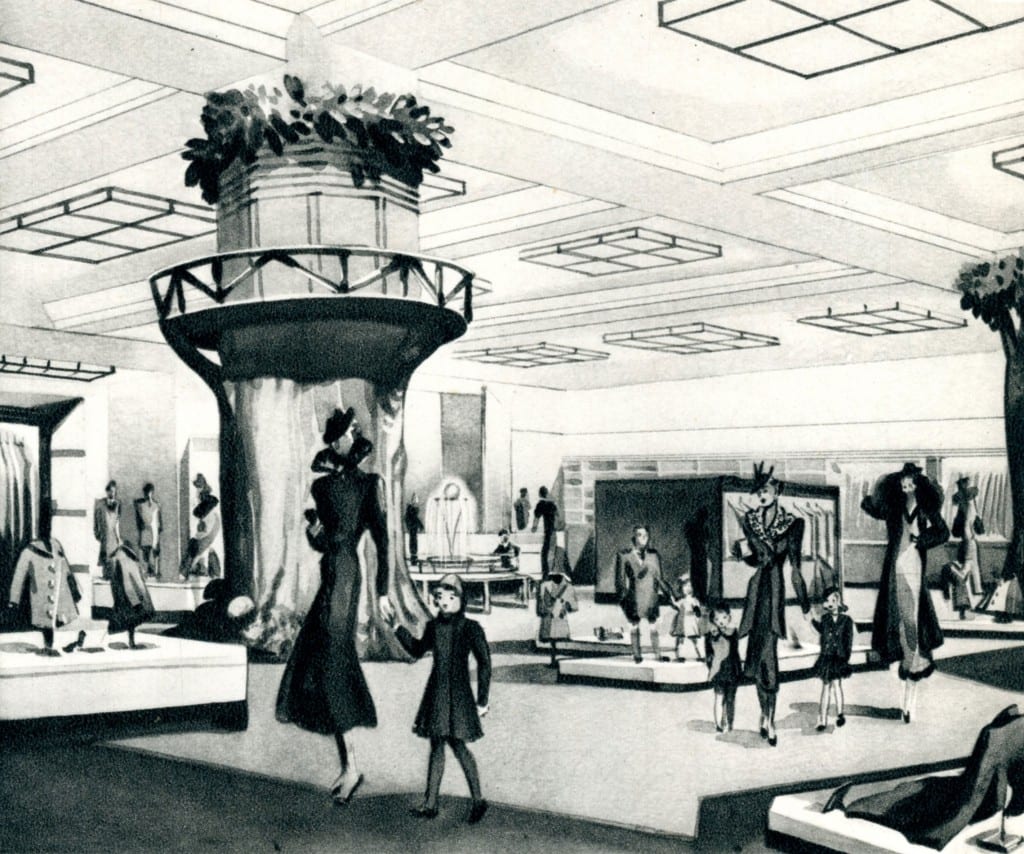

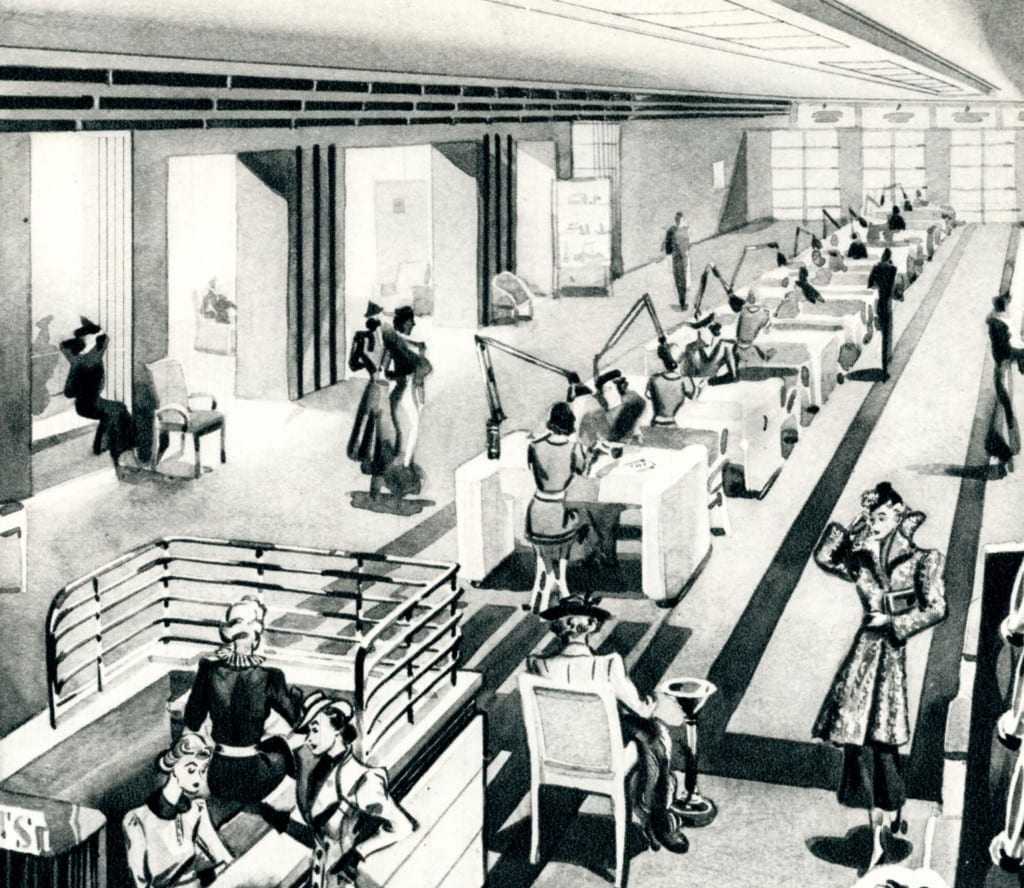

After the Pantheon branch opened in October 1938, an article in a trade magazine remarked that it was ‘designed and equipped on lavish lines’, incorporating features more commonly found in department stores. [5] The ground floor was devoted to sales, with approximately 2,200 feet of counter displays, garment rails and wall racks in an open-plan arrangement. The main retail departments were food, clothing, millinery, footwear and household goods. Extravagant decorative finishes included walnut counters and wall panelling, coffered ceilings and oak block floors laid in a basket weave pattern. Specialist technology in the store included a clock with a signalling system for managerial staff and pillars capped by aluminium light reflectors and grilles for heating and ventilation. A café at the back of the shop adopted a bold, streamlined style based on Wanamaker’s luncheonette in Philadelphia, with curved bars encircled by tall fixed stools with red-leather upholstery. A ladies’ writing and rest room was located on the first floor, with an adjoining lavatory and attendants’ office. The store also provided amenities for the welfare and training of nearly 300 employees, who included an interpreter for seven languages. The upper floors of the north range contained offices, a training room, comfortably arrayed rest rooms, and a canteen serving meals at low prices. The basement contained stock rooms with air-conditioned stores for foodstuffs and a loading bay in Great Marlborough Street.

The Pantheon store, photographed in July 1951 after its extension eastwards into 169–171 Oxford Street (The M&S Company Archive, P2/87/195)

In 1951 Marks & Spencer Ltd expanded eastwards into the basement and ground floor of 169–171 Oxford Street. This six-storey speculative block had been built in 1934 by James Carmichael Ltd to designs by Morris de Metz, replacing Vanoni’s restaurant and a shop. It had been mainly occupied from 1935 by Associated Talking Pictures Ltd, for whom the cinema architect George Coles made alterations, but the shop below had been in separate occupation. By this time, Marks & Spencer Ltd had expanded its catering provision for customers with tea and sandwich bars, ice cream counters, and a large self-service cafeteria with seating for 260 people. These additions probably compensated for the shortage of clothing during rationing. After the acquisition of the adjoining property, openings in the party wall were formed to extend the ground-floor shopping area and the basement stock rooms. Additional shopping space was formed by clearing the arcade shopfronts at both premises, restricting the main entrances to narrow lobbies flanked by display cases.

Sales at Marks & Spencer, Oxford Street Pantheon branch, in the early 1960s. Stocking counter in the foreground (Historic England Archive)

The eastern extension at Nos 169–171 was rebuilt in 1962–3 to secure a continuous street front for the enlarged store. The black-granite façade of the original store was extended by four bays, creating a symmetrical and uniform composition that attested to the adaptability of Lutyens’s modular system. A new shopfront had two recessed public entrances flanked by display cases, which admitted customers into an extensive and open-plan shop. The east front was also extended southwards to include 42–43 Poland Street. In the 1970s, a series of extensions tripled the area devoted to retail space. Lewis & Hickey oversaw a first-floor extension and the rebuilding of the rear of the store in 1971–2. A substantial five-storey range fronting Great Marlborough Street was constructed with irregular fenestration, grey-slate cladding interspersed with raised brown-brick panels, and a steep mansard roof. Public staircases, lifts and escalators on the ground floor ascended to a first-floor sales floor, with an adjoining stock room in the north range. A basement sales floor opened in 1978, increasing the retail space to 93,100 square feet arranged over three main floors. Around this time, the east front in Poland Street was rebuilt on an extended footprint to similar designs prepared by Lewis & Hickey, with a brown-brick and grey-slate elevation. The addition of a second-floor sales area followed. Successive refurbishments of the interior have left no original features behind the black-granite front.

The Pantheon store, photographed in March 1963 during construction works to extend the black-granite façade (The M&S Company Archive, P2/87/195)

References

1. Israel Sieff, Memoirs, 1970, pp. 141–60.

2. Patrick Hickey, cited by Asa Briggs, Marks & Spencer, 1884–1984, 1984, p. 47.

3. Lewis & Hickey, Sixty-Two Years Association with Marks & Spencer, 1984: Kathryn Morrison, English Shops and Shopping, 2003, p. 230.

4. Neil Burton, ‘Robert Lutyens and Marks & Spencer’, Thirties Society Journal, no. 5, 1985, pp. 8–17.

5. The Chain and Multiple Store, 22 October 1938.

Close

Close