Colouring London

By the Survey of London, on 4 October 2019

Some of our readers will have noticed the Survey of London’s recent appearance alongside Layers of London in The Telegraph, which published an interview with Peter Guillery under the title ‘Meeting the historians bringing London’s past to life with maps’. We would now like to share tidings of an inspiring map-based project that is working to advance understandings of London’s history and evolution, while contributing to issues relating to its future. Colouring London is a new crowdsourcing platform designed to collect information on every building in the capital, launched formally only yesterday. This innovative project has been developed by the Centre for Advanced Spatial Analysis (CASA), part of the Bartlett Faculty of the Built Environment at University College London, with funding from several academic and government organizations. The Greater London Authority, Historic England and the Ordnance Survey are core partners. The Survey of London is one of the project’s collaborators, offering advice on how to incorporate historical detail and sharing data from current research in Marylebone, Oxford Street and Whitechapel.

The Colouring London website, showing building age data in Camden

Colouring London has been designed to collect and visualize information about the built environment, inviting participation from any and all. The website provides a free knowledge exchange platform for data relating to all of the capital’s buildings and structures. As users contribute data, the footprints of individual buildings are colour-coded instantly to build legible maps about the city. In addition to submitting information, reading and interpreting the maps, users will be able to download the data. The website is currently in the early stages of testing, which makes your involvement and feedback all the more important. This blog post offers some guidance on contributing to Colouring London by mining for data in the Survey of London series, an essential source for information about the city’s buildings and places.

Polly Hudson, a researcher at the Bartlett and the instigator of Colouring London, has designed the website to harness information on building age, characteristics and lifespans. Data on the built environment is currently incomplete, fragmented and inaccessible, as organizations are slow or reluctant to release information to the public. The difficulty of collecting information about buildings and places is at odds with its inherent value. The Survey of London traces its beginnings to the Arts and Crafts architect, designer and social thinker Charles Robert Ashbee, who believed that to mark down a record of the historic environment is an essential and enriching public good. In the present day, accurate and comprehensive data about the city is also instrumental for urban analyses that contribute to research on significant issues, from sustainability to the housing crisis. These data also feed into scientific research on the reduction of energy use through the adaptive reuse of buildings and the use of predictive models relating to the vulnerability and resilience of cities in the future. For this type of research to be successful, knowledge needs to be converted into numerical data.

In the long term, there are plans for Colouring London to collect, store and visualize a broad spectrum of data relating to the built environment, spanning twelve categories such as land use, building type, designer and constructional details. For the initial testing phase of the project, a smaller number of categories have been launched, including:

Location

Location: This category covers the basic but essential data required to locate buildings accurately, such as address and coordinates. The colours on the map indicate the percentage of data collected. This screenshot shows that the locational information for King’s Cross Station and St Pancras Station is almost complete, whereas smaller buildings in the neighbouring streets are still waiting to be coloured in.

Age

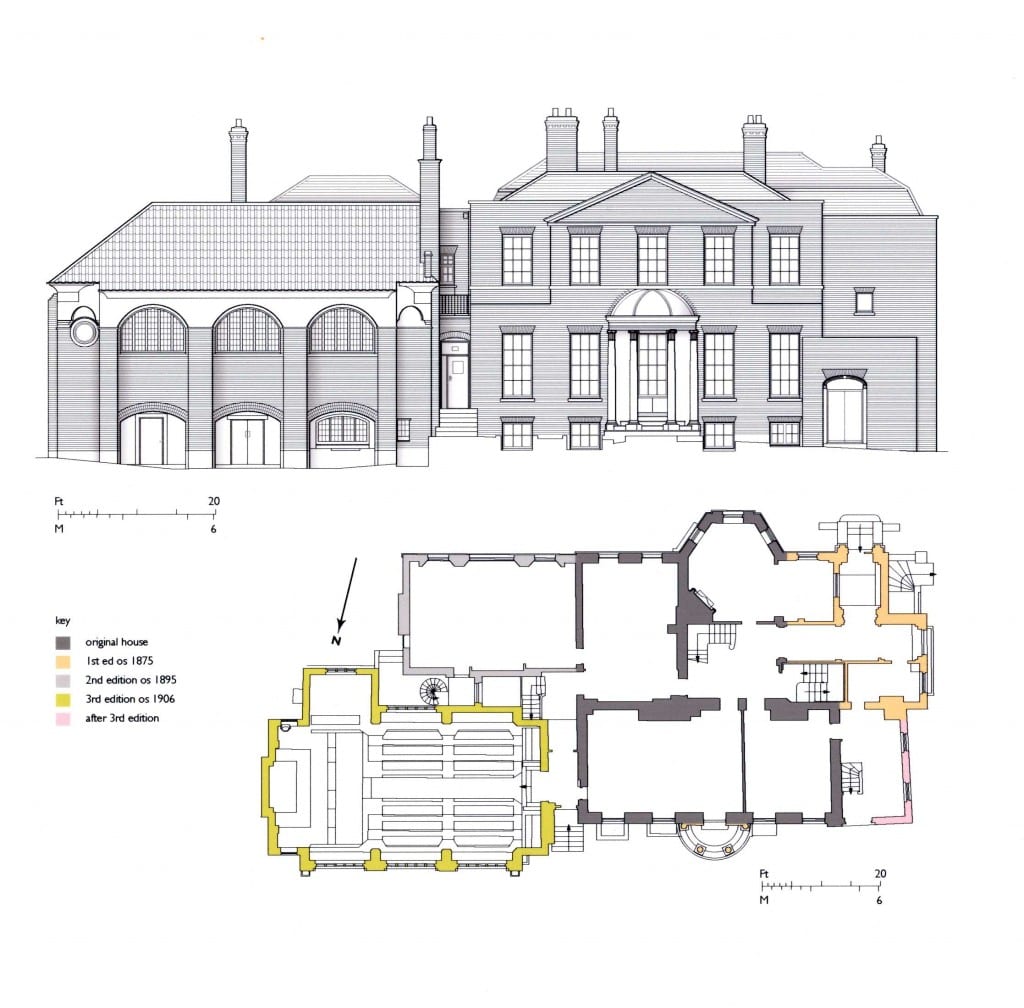

Age: This section includes estimated construction date and façade date, with options to add sources and links. This screenshot shows the grid of streets east of Langham Place, covered in the Survey of London’s South-East Marylebone volumes (published in 2017). If you have used the Survey’s volumes to find construction dates, please use the drop-down box to mark ‘Survey of London’ and include a link to the online version.

Size and shape

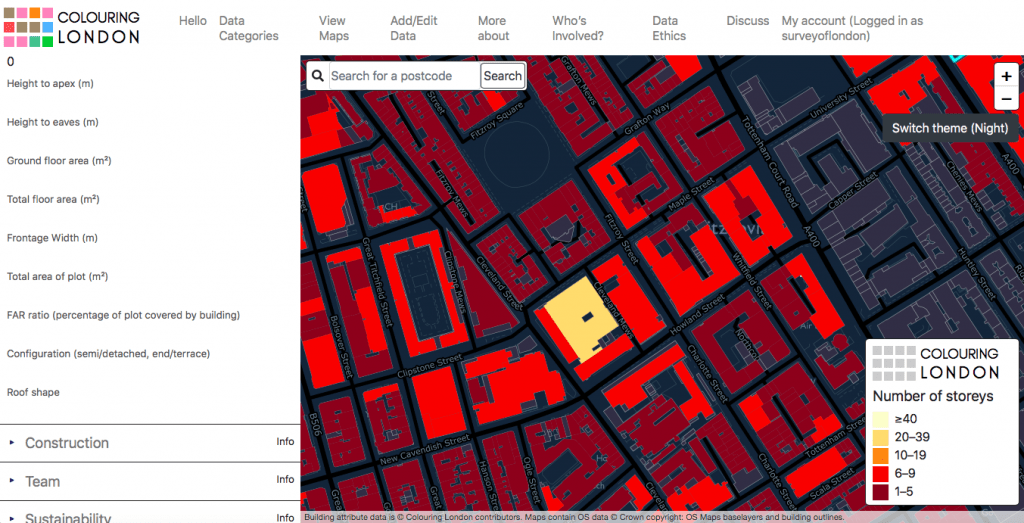

Size and Shape: This category relates to the form of the building, including the number of storeys, height and area. This screenshot shows the streets lying west of Tottenham Court Road and expresses the height of the Post Office Tower in relation to its neighbours.

Planning

Planning: This category links the building to conservation areas, local lists and the National Heritage List for England administered by Historic England. This screenshot shows buildings which are located in conservation areas around Aldwych and the Strand.

Like me

Designed to welcome positivity and inclusivity, the ‘like me’ function is a tick-box inviting users to pinpoint buildings that are admired and thought to contribute to the city. This screenshot shows the British Museum and Bedford Square.

Since its beginnings in 1894, the Survey of London has amassed a wealth of information about the city, its districts and buildings. Fifty-two ‘main series’ volumes, which generally cover historic parishes, and eighteen monographs on individual sites of particular interest have been published, with the next ‘main series’ volume on Oxford Street expected to follow in Spring 2020. The hallmark of the Survey of London series is accessible and readable writing, based on a combination of detailed archival research, secondary sources and field investigation. The volumes contain a vast amount of reliable information – data, essentially – relating to the construction, form and evolution of buildings over time. All of these data may be uploaded to Colouring London.

It is possible to sign up to the Colouring London website within a few minutes, and start colouring building footprints immediately by adding data. If you would like to focus on making contributions about a particular building, street or area, please start by referring to the Survey’s Map of Areas Covered (see below). This map provides a guide to the geographical remit of each volume in the series. From here, a catalogue on our website contains links to online versions of volumes, available via British History Online or in the form of draft chapters uploaded to our website. The detail and scope of the volumes vary significantly, with a shift from the 1970s towards a more inclusive and contextual approach. Today the Survey aims to deal with buildings of all types and dates; with this in mind, it may be worth turning to the latest volumes if you would like to produce a fairly comprehensive map of a particular area. On the other hand, referring to earlier volumes will present an interesting challenge, with the opportunity to trace separately the recent history and evolution of a street or wider area.

Map of areas covered by the Survey of London (please click here to download a pdf version)

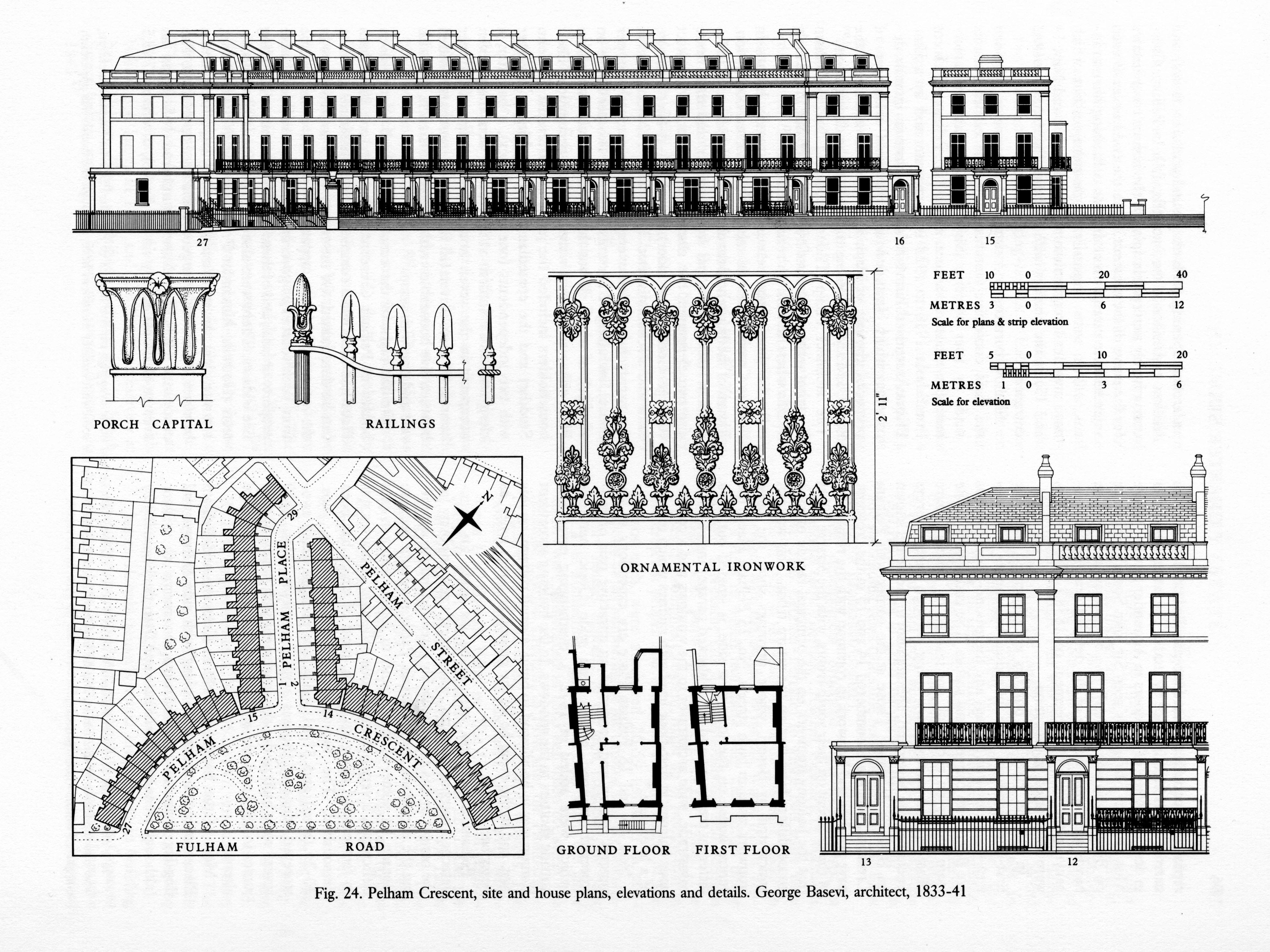

Alternatively, contributors to Colouring London could upload information from one of many gazetteers printed in Survey of London volumes. These lists contain concise descriptions and facts, such as key dates, architects and builders. Maps printed in the volumes will assist in comparing buildings listed in the gazetteer to building footprints on the Ordnance Survey’s MasterMap, which is the base for Colouring London. If you are not familiar with a particular street, it is worth visiting it in person or referring to online street views to check whether buildings still exist.

Gazetteers in recent volumes:

Volume 46, South and East Clerkenwell (2008)

Volume 47, Northern Clerkenwell and Pentonville (2008)

- King’s Cross Road and Penton Rise area

- Amwell Street and Myddelton Square area

- Percy Circus area

- The Angel and Islington High Street

- Pentonville Road

- Rosebery Avenue

Volume 48, Woolwich (2012)

Volume 50, Battersea (2013)

Volume 51, South-East Marylebone (2017)

- Marylebone High Street

- Cavendish Square

- Portland Place

- Queen Anne Street and Chandos Street

- Devonshire, Weymouth and New Cavendish Streets

Volume 52, South-East Marylebone (2017)

Populating Colouring London with age data from Survey volumes

If you are entering construction dates on Colouring London, please use the drop-down box to indicate the source and include a link to the online version of the relevant publication. This screenshot shows Farringdon Road, covered in the Survey’s Clerkenwell volumes (2008). For the purpose of simplicity, the database does not allow ranges to be entered. When the construction date for a building is listed as a range (such as 1882–3), please choose the earliest date (1882). If the façade date differs from the remainder of a building (for example, in cases of façade retention), please enter it in the box below.

We hope this guide will inspire our readers to contribute to Colouring London, and make use of the wealth of information collected and compiled by the Survey of London. This innovative website provides an exciting opportunity to collaborate with a broad network of people – from architects, historians and amenity groups to citizen scientists, local residents and students – to produce beautiful and meaningful maps of London.

Useful links

Close

Close