Whitechapel Bell Foundry

By the Survey of London, on 14 May 2021

It was announced today that permission is to be granted for a hotel conversion of the Whitechapel Bell Foundry. It is timely, and sad, to repost this account from December 2016.

On 2 December it was announced that the Whitechapel Bell Foundry will close in May 2017. This will mark the end of what has been a remarkable story. Business cards claim the bell foundry as ‘Britain’s oldest manufacturing company’ and ‘the world’s most famous bell foundry’ – the first not readily contradicted, the second unverifiable but plausible. It has been said that the foundry ‘is so connected with the history of Whitechapel that it would be impossible to move it without wanton disregard of the associations of many generations.’[1] The business, principally the making of church bells, has operated continuously in Whitechapel since at least the 1570s, on its present site with the existing house and office buildings since the mid 1740s.

Shopfront at the east end of 32–34 Whitechapel Road in 2010 (© Historic England Archive, photographed by Derek Kendall)

The foundry’s origins have been traced to either Robert Doddes in 1567 or Robert Mot in 1572, giving rise to a traditional foundation date of 1570. It is said then to have been in Essex Court (later Tewkesbury Court, where Gunthorpe Street is now). There is no continuous thread, but it has also been suggested that the Elizabethan establishment had grown out of a foundry in Aldgate that can be tracked back to Stephen Norton in 1363.

Whitechapel Bell Foundry in 2010, from the north-east at the corner of Whitechapel Road and Plumber’s Row (© Historic England Archive, photographed by Derek Kendall)

From 1701 Richard Phelps was in charge. He made the great (5¼ ton) clock bell for St Paul’s Cathedral in 1716. When he died in August 1738 he was succeeded by Thomas Lester, aged about 35, who had been his foreman. It has been supposed that within the year Lester had moved the foundry into new buildings on the present site on Whitechapel Road, a belief which can be traced to Amherst Tyssen’s account of the history of the foundry in 1923, where he related that ‘according to the tradition preserved in the foundry and communicated to me by Mr John Mears more than sixty years ago, Thomas Lester built the present foundry in the year 1738 and moved his business to it. The site was said to have been previously occupied by the Artichoke Inn.‘[2] That has never been corroborated and it is implausible as such a move would take more than a few months.

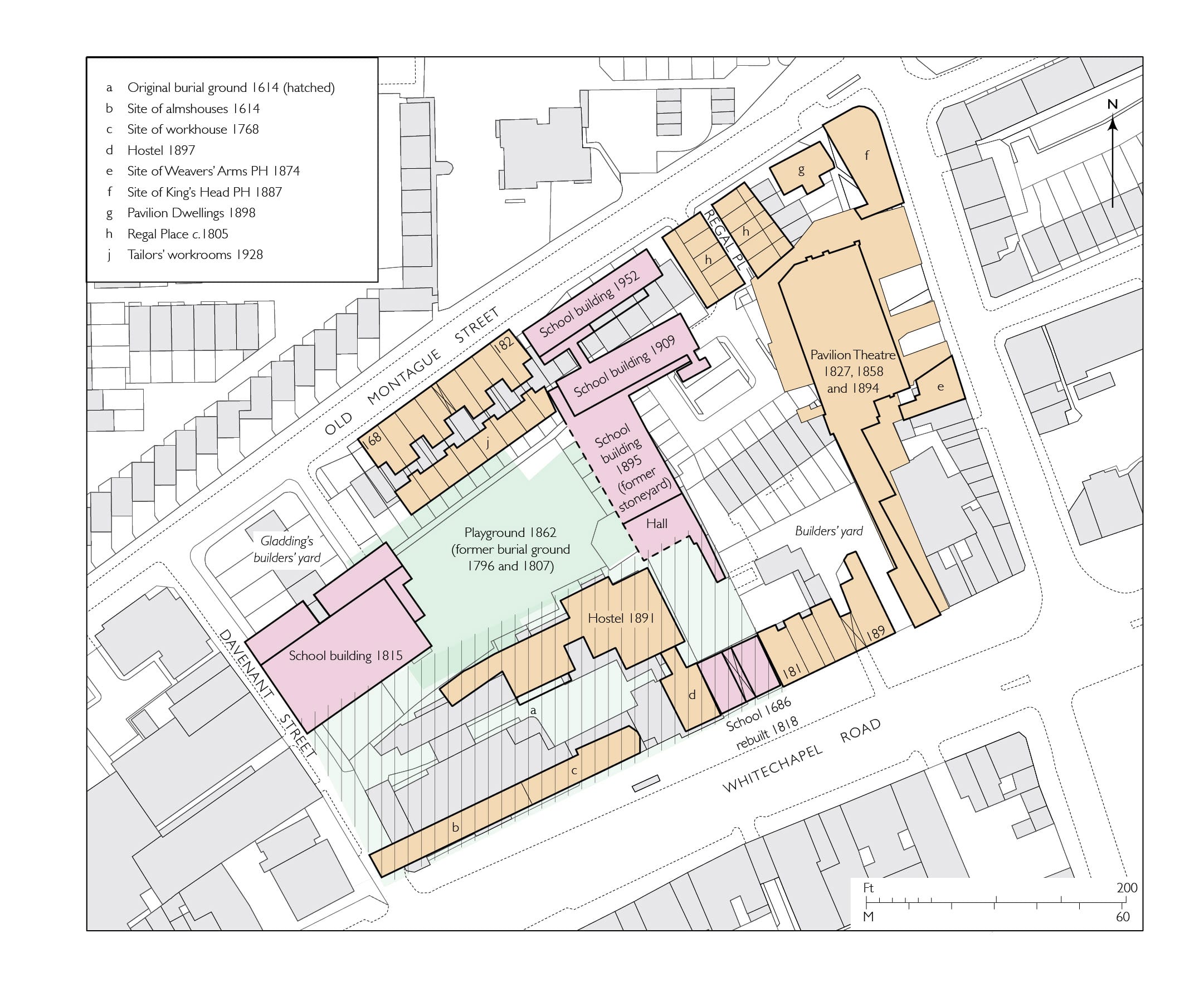

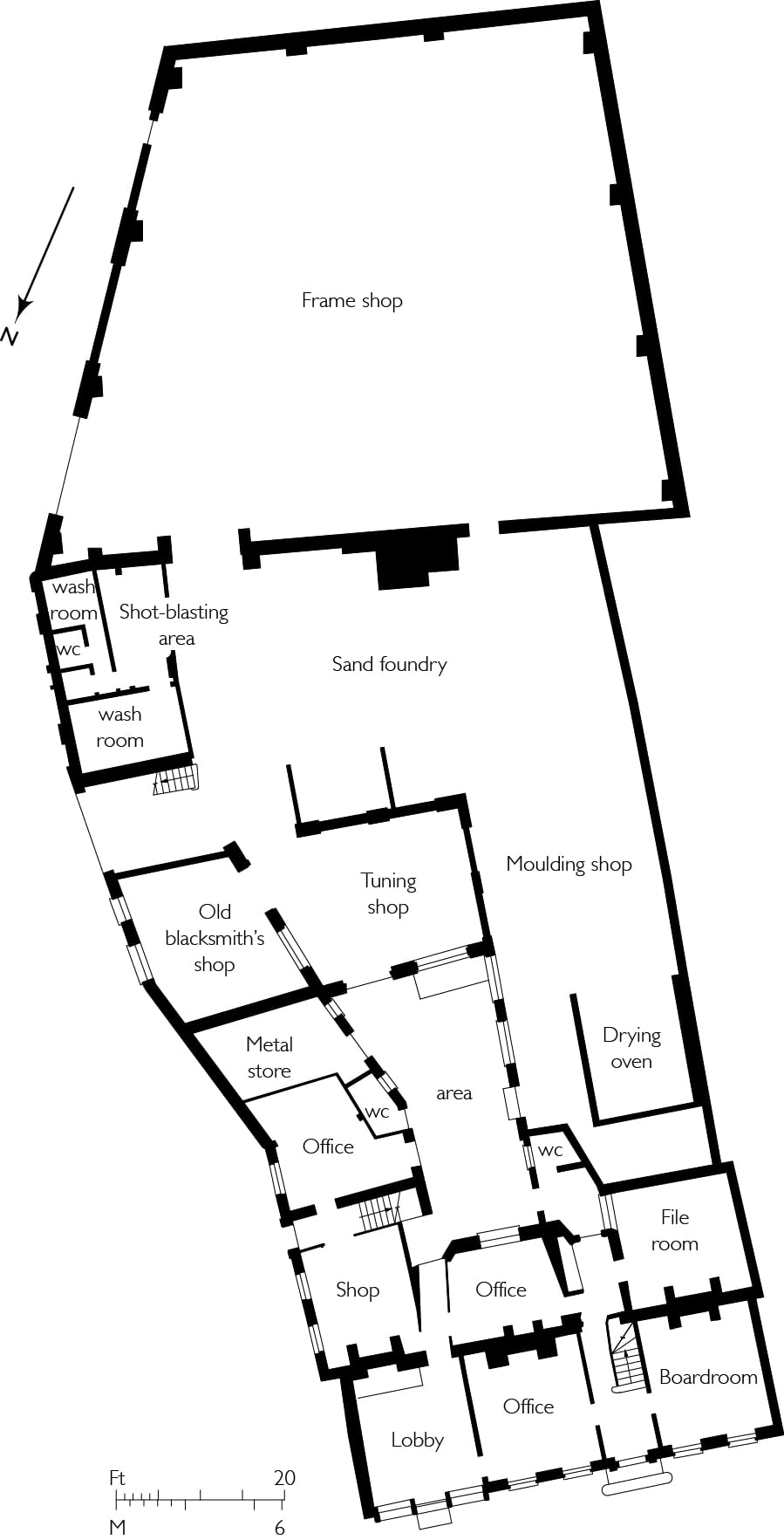

Ground-floor plan of the Whitechapel Bell Foundry (Survey of London, Helen Jones)

Contemporary documentation suggests a slightly later date for the move. An advertisement in the Daily Advertiser of 31 August 1743 reads: ‘To be let on a Building Lease, The Old Artichoke Alehouse, together with the House adjoining, in front fifty feet, and in Depth a hundred and six, situated in Whitechapel Street, the Corner turning into Stepney Fields.’ Those measurements tally well with the foundry site. Stepney Manor Court Rolls (at London Metropolitan Archives) refer to ‘the Artichoke Alehouse, late in the occupation of John Cowell now empty’ on 8 April 1743 and to ‘a new built messuage now in possession of Thomas Leicester, formerly two old houses’ on 15 May 1747. A sewer rates listing of February 1743/4 does not mention Lester at the site. The advertised building lease was no doubt taken by or sold on to Lester, who undertook redevelopment of the site in 1744–6, clearing the Artichoke. The motive for the move would have been the opportunity for a larger foundry and superior accommodation on this more easterly and therefore open site.

View of the Bell Foundry’s workshops from the roof of the front range, looking south in 2010 (© Historic England Archive, photographed by Derek Kendall)

The seven-bay brick range that is 32 and 34 Whitechapel Road is a single room deep with three rooms in line on each storey, all heated from the back wall. It was built to be Lester’s house and has probably always incorporated an office. The Doric doorcase appears to be an original feature, while the shopfront at the east end is of the early nineteenth century, either an insertion or a replacement. Internally the house retains much original fielded panelling, a good original staircase, chimneypieces of several eighteenth- and nineteenth-century dates and, in the central room on the first floor, a fine apsidal niche cupboard. Behind the east end is 2 Fieldgate Street, a separately built house of just one room per storey, perhaps for a foreman. Its Gibbsian door surround is of timber, as is its back wall.

The ground-floor front ‘lobby’ (former shop) at 34 Whitechapel Road in 2010, showing the casting profile of Big Ben over the front door (© Historic England Archive, photographed by Derek Kendall)

Eighteenth-century outbuildings to the south are single storeyed: a former stables, coach-house and smithery range along Fieldgate Street; and the former foundry (latterly moulding shop) itself, across a yard behind the west part of the house. Facing the street on the former stabling range is a tablet inscribed: ‘This is Baynes Street’ with an illegible date, perhaps 1766, a reference to what later became Fieldgate Street. This junction, which now incorporates Plumber’s Row, bisected property owned by Edward Baynes from 1729.

Plumber’s Row range in 2010 (© Historic England Archive, photographed by Derek Kendall)

Tablet inscribed ‘This is Baynes Street’ on the foundry’s former stabling range (© Historic England Archive, photographed by Derek Kendall)

Thomas Lester took Thomas Pack into partnership in 1752 and acquired ownership of the foundry from a younger Edward Baynes in 1767. Lester’s nephew William Chapman was a foundry foreman who, working at Canterbury Cathedral in 1762, met William Mears, a young man he brought back to London to learn the bell-founding trade. Lester died in 1769 and left the foundry to relatives to be leased to Pack and Chapman as partners. After Pack died in 1781 Chapman was pushed out and for a few years descendants of Lester ran the establishment. Their initiative failed and William Mears returned in partnership with his brother Thomas, who came to Whitechapel from Canterbury. Ownership of the property remained divided among descendants of Lester and in 1810 Thomas Mears was still trading as ‘late Lester, Pack and Chapman’. On a promotional sheet he listed all the bells cast at the foundry since 1738, 1,858 in total, around 25 per year – including some for St Mary le Bow in 1738, Petersburg in Russia in 1747, and Christ Church, Philadelphia, in 1754.

Inner yard of the bell foundry, looking north-west in 2010 (© Historic England Archive, photographed by Derek Kendall)

A son, also Thomas Mears, acquired full control of the foundry in October 1818 when Lester’s descendants sold up. The younger Mears took over the businesses of four rival bell-founders and undertook works of improvement. By 1840 the firm had only one major competitor in Britain (W. & J. Taylor of Oxford and Loughborough). The next generation, Charles and George Mears, ran the foundry from 1844 to 1859, the highlight of this period being the casting in 1858 of Big Ben (13.7 tons), still the foundry’s largest bell. From 1865 George Mears was partnered by Robert Stainbank. Thereafter the business traded as Mears & Stainbank up to 1968. Arthur Hughes became the foundry manager in 1884 and took charge of operations in 1904.

Inner yard of the bell foundry, looking south in 2010 (© Historic England Archive, photographed by Derek Kendall)

Given the ownership history, there was little significant investment in the buildings before 1818. However, the smithery end of the eastern outbuilding does appear to have been altered if not rebuilt between 1794 and 1813. Around 1820 a small pair of three-storey houses was added beyond a gateway that gave access to the foundry yard. There are also early nineteenth-century additions behind the centre and west bays of the main house, the last room incorporating a chimneypiece bearing ‘TM 1820’. Thereafter, possibly following a fire in 1837 or in the 1850s, the smithery site was redeveloped as a three-storey workshop/warehouse block extending across a retained gateway. In 1846 the foundry was enlarged with a new furnace by enclosing the south end of the yard, to make an 11.5 ton bell for Montreal Cathedral. Another furnace was added in 1848 when a tuning machine was housed in a specially built room that ate further into the yard with a largely glazed north wall. Two years later a 62ft-tall chimney was erected against the south wall. A large additional workshop or back foundry had been added to the far south-west by the 1870s, by when the pair of houses to the south-east had been cleared for a carpenter’s shop, the front wall retained with its doors and windows blocked. The whole Plumber’s Row range has latterly been used for making handbells and timber bell wheels.

Handbell workshop in 2010 (© Historic England Archive, photographed by Derek Kendall)

Moulding shop, showing moulds being prepared in 2010 (© Historic England Archive, photographed by Derek Kendall)

The back foundry was damaged during the Second World War. Proposals to rebuild entirely behind the Whitechapel Road houses emerged in 1958 by when the foundry was already protected by listing. The workshops were considered expendable, but even then it was suggested that the timber jib crane on the east wall should be preserved. First plans were shelved and a more modest scheme of 1964–5 was postponed for want of capital, though plant and furnaces were replaced and there were repairs. In 1972 Moss Sprawson tried to acquire the site for office development. For the foundry, Douglas Hughes (one of Arthur’s grandsons) proposed a move east across Fieldgate Street to what was then a car park owned by the Greater London Council. A move entirely out of London was also considered. The GLC’s Historic Buildings Division involved itself in trying to maintain what it considered ‘a unique and important living industry where crafts essentially unchanged for 400 years are practised by local craftsmen.’[3] But plans came unstuck again in 1976 when the GLC conceded it had no locus to help keep the business in situ. In the same year the UK gave the USA a Bicentennial Bell cast in Whitechapel.

A large new engineering workshop was at last built in 1979–81, with James Strike as architect. At the back of the site, it was faced with arcaded yellow stock brick on conservation grounds. In 1984–5 the GLC oversaw and helped pay for underpinning and refurbishment of the front buildings. The shopfront was grained and the external window shutters were renewed and painted dark green. In 1997 proprietorship passed to Douglas Hughes’s nephew, Alan Hughes, and his wife, Kathryn. The foundry has since continued to manufacture, though not without growing concerns as to its tenability in Whitechapel. Now the Hughes have announced that the foundry will close in May 2017 after sale of the site. The future of the business is to be negotiated.

We are very grateful to Alan Hughes for showing us round the premises and sharing his knowledge of the foundry.

The Survey of London has launched a participative website, ‘Histories of Whitechapel’. Please visit at: https://surveyoflondon.org. We welcome contributions from any and all. For more information about the Whitechapel Bell Foundry, and to add your memories and photographs, please visit https://surveyoflondon.org/map/feature/155/detail/.

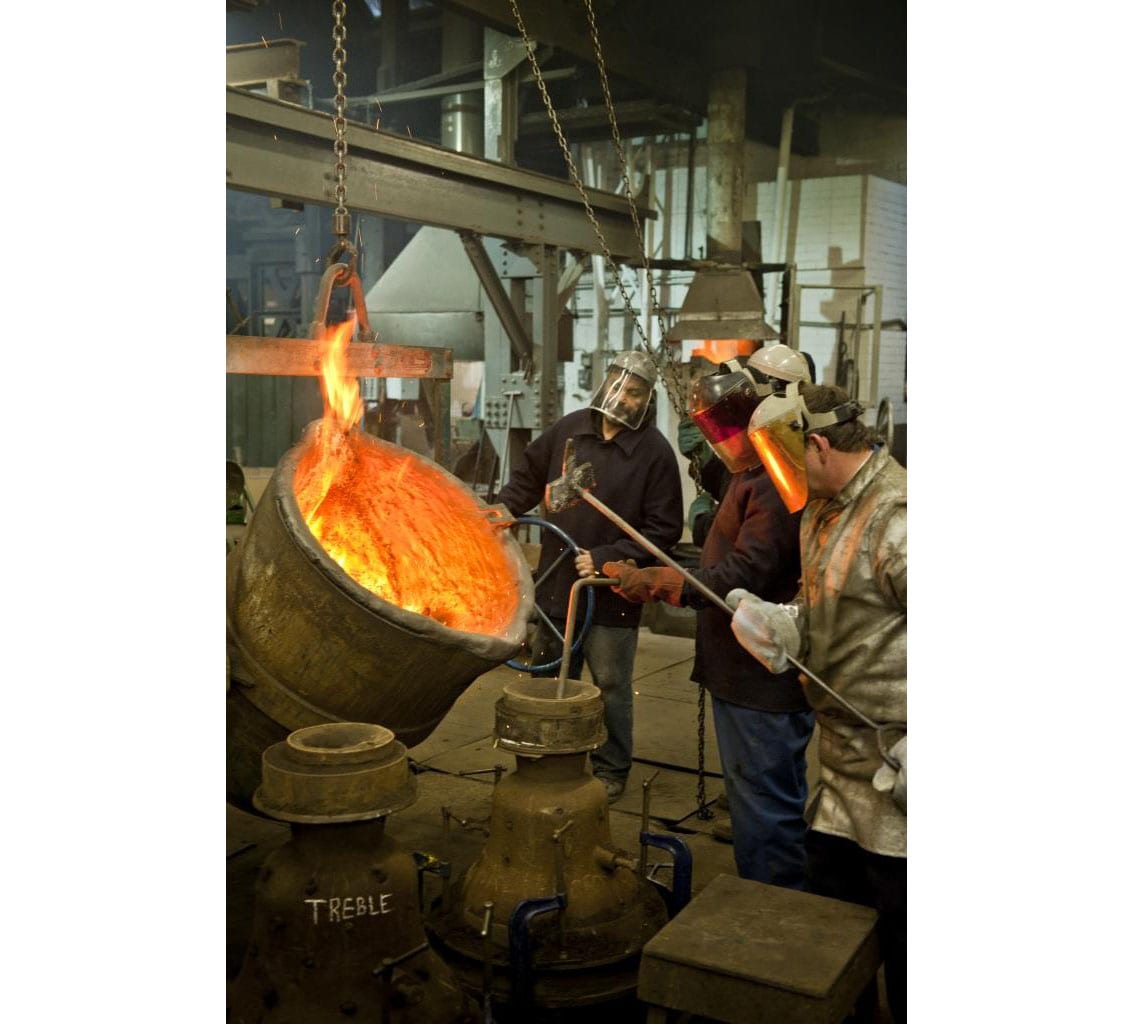

Sand foundry, filling the moulds in 2010 (© Historic England Archive, photographed by Derek Kendall)

Tuning shop in 2010 (© Historic England Archive, photographed by Derek Kendall)

Bell recast in 2010 (© Historic England Archive, photographed by Derek Kendall)

References

[1] D. L. Munby, Industry and Planning in Stepney, 1951, p. 254

[2] Amherst D. Tyssen, ‘The History of the Whitechapel Bell-Foundry’, Transactions of the London and Middlesex Archaeological Society, vol. 5, 1923, p. 211

[3] London Metropolitan Archives, LMA/4441/01/0821

Close

Close