The Central Synagogue, Great Portland Street

By the Survey of London, on 17 March 2017

The present synagogue was built to designs by C. Edmund Wilford & Sons in 1956–8, replacing its bomb-damaged predecessor of 1869–70.

Central Synagogue, Great Portland Street, Marylebone, Greater London. Exterior view from north east. Taken in 2013 for the Survey of London by Chris Redgrave. © Historic England

Jewish West Enders were obliged until well into the nineteenth century to attend long-established places of worship in the City of London, notably the Great Synagogue in Duke’s Place, Aldgate. In 1842 the Reform congregation broke this tradition with a modest synagogue in Burton Street, Bloomsbury, moving to Margaret Street in 1849. Fearing loss of worshippers to this convenient address, the Committee of the Great Synagogue agreed in 1850 to fund a new branch synagogue in the West End. The site selected lay behind 43–47 Great Portland Street, but the building there soon proved too small and could not be extended. In 1866 a Great Synagogue subcommittee headed by Sir Anthony de Rothschild was appointed to find a new site near by and build afresh for 800 worshippers, with two ministers’ houses attached. They promptly secured the houses at 133–141 Great Portland Street. The budget was ample, as the synagogue was prospering; Messrs Rothschild had promised £4,000. The committee decided against a competition and chose as architect Nathan Solomon Joseph, son-in-law to Nathan Marcus Adler, Chief Rabbi and creator of the United Synagogue, the federation to which the Central, as the congregation was by now called, adhered from 1870. Joseph presented a Moorish design in 1867, arguing that Gothic and Classical styles were both unsuitable, whereas the Moresque was well adapted to an ‘ecclesiastical’ building yet had advantages of ‘elasticity’ and economy. He was asked to present an alternative Italianate version, but the original was preferred, with modifications. That design was built in 1869–70.

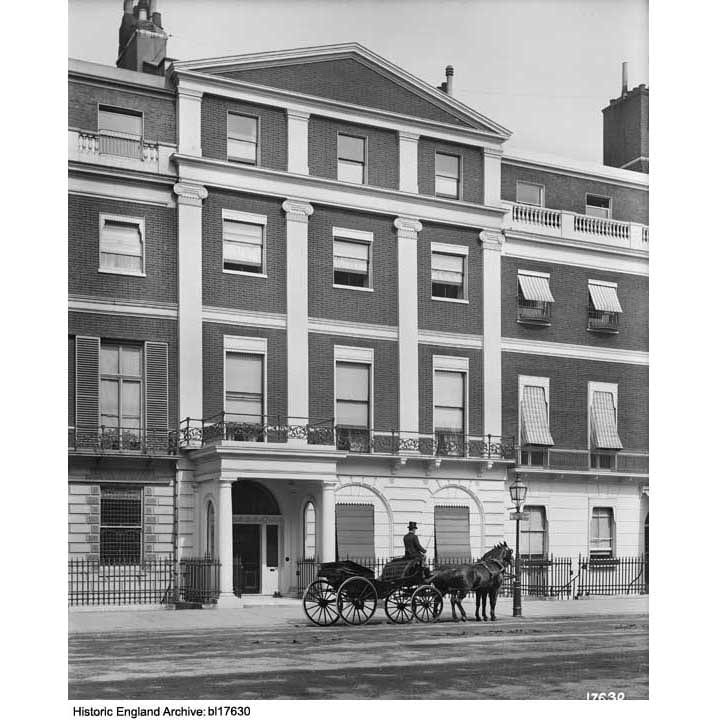

40-36 Hallam Street, Westminster, London. View from west. Photographed in 2014 by Lucy Millson-Watkins for the Survey of London © Historic England

The Central has been described as the first thoroughly Oriental-style synagogue, not just in Britain but beyond. The Great Portland Street front was an eccentric confection in brick and two types of stone, culminating at the north end in a tower-like feature over an entrance porch with a horseshoe arch. The interior, spacious, high and light, faced south like the present building, culminating in a richly decorated apsidal space for the ark. Windows and arches were round-headed, with an orientalizing horseshoe profile above the arches over the galleries, and round clerestory lights incorporating Star-of-David tracery. Cast-iron columns, painted at first, marble-clad from 1876, carried the galleries and roof, which was divided by ribs. The rabbis’ houses at the back along Hallam Street (Nos 36–40) survive, their two-tone brickwork and Moorish detail having a hint of the Great Mosque at Cordoba. Embellishments took place over the years, the grandest being the replacement of the central almemar with an elaborate new one in marble, presented in 1928 by the 2nd Lord Bearsted in memory of his parents; Joseph’s original almemar (or bimah) was relegated to the Margate synagogue. But the building was burnt out by a fire bomb on 10 May 1941, the congregation returning to a temporary building on the site in 1948.

Central Synagogue, Great Portland Street, Marylebone, Greater London. Interior view from south east. Photographed in 2013 for the Survey of London by Chris Redgrave. © Historic England

Meanwhile plans for a full rebuilding were hatching. The architects Shaw & Lloyd worked up a radical proposal in 1947, with the synagogue turned across the axis from Great Portland Street to Hallam Street, set over social space and flanked by narrow courts, with a taller block at the back facing Hallam Street, presumably for letting. Having done all the war-damage costings and negotiations, in 1954 S. John Lloyd presented a fresh scheme for a 1,028-seater, to be built of reinforced concrete with a Portland stone front to Great Portland Street.

Central Synagogue, Great Portland Street, Marylebone, Greater London. Detail of the Tebah from north east. Photographed in 2013 for the Survey of London by Chris Redgrave. © Historic England

There were tensions at this juncture, as the United Synagogue authorities were pressing for a fresh place of worship at Marble Arch and the abandonment of the Central. Isaac Wolfson and his son Leonard, resident in Portland Place, resolved things by offering £25,000 towards rebuilding the Central, which meant that, with war-damage compensation, rebuilding would cost the congregation little. The United Synagogue sent a long list of possible architects to the building committee, who shortlisted three, not including Shaw & Lloyd. At Leonard Wolfson’s request they added an outsider, C. Edmund Wilford. It seems that Wilford had shown him some sketches which, United’s president Ewan Montague agreed, showed ‘a most interesting approach to the theme of Synagogue architecture which hitherto in our experience has tended to be somewhat hackneyed’. But when Wilford was confirmed and met the building committee, he was told that the external elevation ‘should be on traditional lines’. [1]

Wilford had made a name with cinemas before the war. He had no known connection with the Jewish community, but may have worked for the Wolfsons’ company, Great Universal Stores. He and his assistants were directed to look at synagogues in London and perhaps also Venice. The result, built by Tersons Ltd in 1956–8, was a conventional, dignified building with close correspondences to its predecessor but an internal touch of cinematic glamour.

Central Synagogue, Great Portland Street, Marylebone, Greater London. Detail showing Torah Ark. Photographed in 2013 for the Survey of London by Chris Redgrave. © Historic England

The Great Portland Street façade is mainly clad in Portland stone, but the plinth and the columns flanking the high and hooded windows are of red Swedish granite. At the north end the entrance doors are set back in a high frame clad in gold mosaic. There is also a subsidiary entrance from Hallam Street. The galleried interior gives a powerful impression of height and restrained opulence.

Central Synagogue, Great Portland Street, Marylebone, Greater London. View of east windows. Taken for the Survey of London in 2013 by Chris Redgrave. © Historic England

The focus is on the ark at the south end, which stands in an outer surround of red mosaic embellished by flanking lions on tall pillars of gold and an inner frame of Sienna marble. The bronze metalwork to the ark doors and elsewhere, made by the Brent Metal Company, is strong, spiky and characteristically 1950s. The other main feature is the almemar, clad in red marble, with attached panels carved in low relief.

Central Synagogue, Great Portland Street, Marylebone, Greater London. Detail showing east stained glass window. Photographed in 2013 for the Survey of London by Chris Redgrave. © Historic England

After completion, the synagogue windows were filled over a fifteen-year period with colourful glass made by Lowndes & Drury to designs by David Hillman. There is a hall below the worship area, and the circulation spaces including the stairs to the galleries are generous.

Central Synagogue, Great Portland Street, Marylebone, Greater London. View of stair. Photographed in 2013 for the Survey of London by Chris Redgrave. © Historic England

Reference

[1] London Metropolitan Archives, ACC/26712/15/2334

South-East Marylebone Old and New

By the Survey of London, on 24 February 2017

In 2017 the Survey of London will publish two volumes (Nos 51 and 52) covering a large swathe of the parish of St Marylebone, an area comprising much of the West End north of Oxford Street, otherwise bounded by Marylebone High Street and the Marylebone Road, west and north, and Cleveland Street and Tottenham Court Road to the east. Like many of London’s place-names, Marylebone means different things to different people. To some it connotes the Marylebone Road and its penumbra, scarred by grinding traffic, to others the area adjacent to the two Marylebone Stations, main-line and underground, while those with a sense of civic history may call to mind a once-proud parish stretching from Oxford Street through St John’s Wood to the edge of Kilburn. By far the most famous association is with Lords, and the Marylebone Cricket Club founded in 1787. But the enduring image of Marylebone as a district is of the grid of alternating streets and mews, leavened by the occasional square, that picks up the West End’s uncertain structure beyond Oxford Street and shakes it into order and urbanity.

The aura of south-east Marylebone is various. Time-honoured medical connections have bequeathed cosmopolitanism and gravity to the central grid. Here patients for private clinics or guests at serviced apartments and hotels alight at the kerbside, chauffeurs linger on the qui vive for parking attendants, and pedestrians scurry rather than saunter, pressed forward by the rhythm of the streets. A mundane mews behind may be disrupted by a vision of nurses on tea-breaks clad in overall green, or a lorry backing in with oxygen canisters. Marylebone High Street and its boutiques draw their constituency of well-heeled shoppers and loafers. Yet Paddington Street Gardens and Marylebone Churchyard close by convey an air of ease, with old people reflective on benches or gaggles of schoolchildren on the grass. Lunchtime sprawlers in Cavendish Square are different – a mélange of shop assistants, office workers and tourists taking their breaks. On the fringes of Fitzrovia, the livelier portions of Great Titchfield Street and its surroundings exude conviviality, mixing pubs, small shops and cafés even now not all gentrified, patronized by the copious media businesses that have spread outwards from the BBC and taken over the premises of the dwindling garment trade.

Parts of south-east Marylebone have resisted change during the last century. The following photographs taken by Bedford Lemere & Co. at the turn of the nineteenth century are shown alongside recent photographs by Chris Redgrave.

Debenham and Freebody department store during construction, 27–37 Wigmore Street, in 1907 (Historic England Archive)

Former Debenham and Freebody department store, 27–37 Wigmore Street, in 2013 (Historic England, Chris Redgrave)

The south side of Wigmore Street offers a sudden change in scale and monumentality with the silvery bulk of No. 33, built as headquarters for the drapery business of Debenham & Freebody in 1906–7. A public offer was made in 1907 to help pay for a grand reconstruction of the Wigmore Street premises, ‘rambling and incoherent’ after 90 years of piecemeal development. The London Scots architects William Wallace and James Glen Sivewright Gibson were chosen to design the new building. The frontage was conceived as symmetrical across the whole of the block, but because of the bank there is an extra bay at the west end, devoted originally to a discrete fur shop. A giant arcade runs across the ground and first floor, with plate-glass windows to what were originally single large shops either side of the entrance, their semi-circular tops lighting the first-floor showrooms. Three segmental pediments top three bays set slightly forward with paired giant-order Corinthian columns of grey-green Truro marble forming a vestigial screen to the third and fourth floors. Decoration is mostly channelled ‘stone’ work to the first floor, applied garlands, and two seated female figures within the central pediment, all executed in Doulton’s Carrara Ware. Crowning all is a columned lantern-turret on an octagonal plinth.

46 and 48 Portland Place in 1903 (Historic England Archive)

46 and 48 Portland Place in 2013 (Historic England, Chris Redgrave)

Nos 34–60 is the best run of surviving Adam-period houses in Portland Place, still with its eye-catching stuccoed and pedimented central pair at Nos 46 and 48, with their ingenious mirrored angled entrance doors. It is here that one gets the strongest sense of the Adam brothers’ original palace-front design concept. Various alterations have changed the appearance of the middle pair at Nos 46 and 48, marring though not completely obliterating the powerful original composition. Its crowning balustrade has gone but for once, when the upper floor was extended around 1870, rather than building up the front wall as elsewhere in the street, the builders left the central pediment in situ, with an enlarged mansard roof and dormers rising behind. Like its partner opposite (No. 37, now demolished), this façade was faced entirely in stucco and decorated with a frieze, pilasters, roundels and characteristic Adam panels of griffins and urns of the same material. Unusually the rusticated ground floor has the windows flanking the entrance set within relieving arches. Particularly elegant is the shared entrance within a shallow apse under a segmental arch, with the two doorways set at an angle.

28 Portland Place in 1903 (Historic England Archive)

28 Portland Place in 2015 (Historic England, Chris Redgrave)

No. 28 Portland Place retains its Adam pediment and Ionic pilasters (though both were raised in the nineteenth century to accommodate an extra storey), as well as a later Doric entrance porch. Despite many changes it still exudes an aura of old-world elegance. Though it was sold by the Goslings to the Institute of Hygiene in 1928 and has been in institutional or corporate use ever since, No. 28 is still a first-rate example of a London society townhouse adapted and added to over time by one family. The interiors have survived well, of which the most notable is an exceptionally fine ballroom, comprising a suite of linked first-floor drawing rooms fitted out in an elaborate late-Victorian Adam Revival style, with an abundance of painted and gilded plaster decorations and a figurative front-room chimneypiece in the manner of Wyatt.

11 Harley Street in 1903 (Historic England Archive)

11 Harley Street in 2013 (Historic England, Chris Redgrave)

9 and 11 Harley Street are tall red-brick rebuildings, of 1891 and 1886 respectively, in similar styles, with plentiful stone dressings and pediments. No. 9 was designed by F. M. Elgood as a speculation for W. H. Warner (of Lofts and Warner, estate agents). Elgood was also involved in the design of No. 11, one of his earliest works in the area, whilst still in partnership with Alexander Payne (to whom he was articled) as Payne & Elgood. Their client was the physician and surgeon William Morrant Baker. The building was extended to the rear in 1906 for another doctor, the dermatologist J. M. H. McLeod. Stone figures on the gable were removed in 1937.

Bedford & Co. offices at 24 Wigmore Street in 1894, No. 22 to the right (Historic England Archive)

18–24 Wigmore Street in 2014 (Historic England, Chris Redgrave)

Nos 18–22 Wigmore Street were built by Holloway Brothers in 1892–3 to the designs of Leonard Hunt, as showrooms and offices for the piano manufacturer John Brinsmead & Sons. The business, founded in 1837, moved to No. 18 (then 4) in 1863 and subsequently expanded into 20 and 22. The works moved from Charlotte Street to Kentish Town in 1870, and by 1893 produced around 3,000 pianos a year. Hunt’s building, expensively finished with mahogany panelling and leaded glass, was ‘one of the sights of fashionable London’. The ground floor was given over to display space, divided by a hallway with pavement lights illuminating basement showrooms, the upper floor comprising offices and chambers. In 1895 a recital room was added at the back of the basement, seating 130. Lit from two sides with leaded windows, it had mirrored columns and fully-tiled walls. Bedford & Company, surveyors, had offices next door at No. 24. Brinsmeads went out of business in 1922, but was re-established at 17 Cavendish Square in 1924. Lloyds Bank acquired the Wigmore Street building, creating a strong room within the former recital room, and subletting the western shop, which retains a 1928 neo-Georgian bronze shopfront fitted for the opticians Curry & Paxton. The upper floors were converted to flats in 1933.

34 Weymouth Street in 1910 (Historic England Archive)

34 Weymouth Street in 2014 (Historic England, Chris Redgrave)

On the other side of Upper Wimpole Street, of 1908 in a strong, shaped-gable style, is 34 Weymouth Street, by F. M. Elgood for the developer W. H. Warner. Here the gables have oculus windows with attractively sculpted stone surrounds and festoons beneath, the work of A. J. Thorpe, who was also responsible for the carved stone consoles to the door surround.

30–31 Wimpole Street in 1917 (Historic England Archive)

30–31 Wimpole Street (left) and 30a and 30b New Cavendish Street (right) in 2014 (Historic England, Chris Redgrave)

Though treated as one architectural piece, this large and imposing Portland stone corner block of 1910–12, extending round the corner into New Cavendish Street, appears to have been a joint redevelopment and was built as four separate ‘houses’, each originally comprising doctors’ consulting rooms on the lower floors and residential accommodation above. The two properties facing Wimpole Street (originally numbered 30 & 31) were designed by F. M. Elgood, working for the developer Samuel Lithgow. But the two houses fronting New Cavendish Street (30a & 30b) were by Banister Fletcher & Sons, acting for Dr James Lennox Irwin Moore, who had consulting rooms at 30a – and it was these two ‘doctors’ houses’ that attracted attention in the architectural press. The style is a muscular free Jacobethan, with mullioned and transomed windows, and a stone balcony resting on decoratively carved console brackets, all topped off by pedimented gables with deep modillion eaves – offering a strong contrast to Wimpole House opposite, with its dressing of florid salmon-pink terracotta. The composition is stylistically dissimilar to most of the Edwardian buildings on the Howard de Walden estate (and is none the worse for that) but there are a few oddities about the design. For instance, above the deep modillion cornice on the New Cavendish Street elevation, instead of gables as elsewhere, broad dormers flank a flat-roofed pavilion with a concave façade in what appears to be Bath stone but is probably coloured render. In terms of their construction, the buildings made use of expanded-steel reinforced concrete, with interiors awash with oak panelling and polished oak to the floors and staircases.

In advance of the publication of Volumes 51 and 52 of the Survey of London, on South-East Marylebone, in 2017, the draft chapters have been made freely available online.

The Grocers’ Company’s Wing of the former Royal London Hospital

By the Survey of London, on 3 February 2017

The long former Royal London Hospital complex on the south side of Whitechapel Road has its origins in the hospital built in 1752–78 to designs by Boulton Mainwaring. Its eastern section was constructed in 1873–6 as part of the Grocers’ Company’s Wing, built at the same time as a Post Mortem Department and Nurses Home. Their completion secured the hospital’s status as the largest general hospital in the country, with almost 800 beds. The only remnant of this building programme is the north range of the Grocers’ Company’s Wing, which presents an orderly 120ft frontage to Whitechapel Road terminating at its junction with East Mount Street. Two bays of the south part of the wing survive; the rest was cleared in the 1960s for the construction of the Holland Wing (demolished).

At the time of writing, the north range of the Grocers’ Company Wing lies empty as the former hospital awaits conversion into a civic centre for Tower Hamlets Council. Despite 140-years of hospital use, the surviving portion of the Grocers’ Company’s Wing retains its back-to-back ‘Nightingale’ wards and neat brick frontage overlooking Whitechapel Road.

The main front of the Royal London Hospital in Whitechapel Road, with the Grocers’ Company’s Wing in the background. Photographed by Derek Kendall in 2016

This significant wing extension was catalysed by rising numbers of inpatients. Despite the completion of the Alexandra Wing in 1866, the hospital struggled to keep pace with demand for beds. In 1870 the House Governor, William Nixon, recorded an ‘extreme pressure of inpatients’, averaging at over 500 at any one time. Despite the opening of quarantine wards in the old medical college, the hospital failed to secure a long-term solution to overcrowding. A few years later, Nixon reported an alarming ‘state of repletion’ in the wards. He declared that the hospital was ‘not large enough’ to fulfil the demands of the surrounding district, despite its strict policy of admitting only urgent cases. [1]

The proposed solution was to extend the hospital to provide 200 additional beds. A public fundraising campaign was launched with the aim of securing £100,000 towards new buildings and the operating costs of an enlarged hospital. A new wing extending east from the front block was deemed preferable to ensure the proximity of new wards to the ‘working centres’ of the hospital, namely the lifts, the staff offices, the laundry, the kitchen, the operating theatre, and the depository. The intended site was occupied by the old medical college and a carriage shed fronting Whitechapel Road, along with various workshops, sheds and stables in East Mount Street.

The Grocers’ Company’s Wing from the north-west. Photographed by Derek Kendall in 2016

The centrepiece of this wave of hospital expansion was the Grocers’ Company’s Wing, named in recognition of a donation from the City livery company. Their ‘princely gift’ was accompanied by numerous conditions, including that the proposed wing should be completed within three years. Whilst the House Committee had intended to postpone work on the new east wing until the fundraising campaign had realised its target, the Company stipulated that construction should begin immediately.

As the projected cost of the wing exceeded £25,000, it was reasoned that sole responsibility for its design should be entrusted to Charles Barry, Consulting Architect to the hospital. He planned an L-plan three-storey wing with basement and attics, composed of two blocks; a north range extending east from the front block in line with Whitechapel Road, and a south range running along East Mount Street. This arrangement preserved a yard between the extension and the main building, with the benefit of supplying light and ventilation to the inward-facing wards. The plan of the principal floors of each block followed the pattern of the earlier ward wings, comprising paired back-to-back wards separated by a central spine wall with fireplaces. On each floor, the north range was accessed from its south-west corner via lobbies connected with the long corridors of the front block. Partitions at the west end of the wards formed linen stores and areas for water closets, kitchens and sinks. The attics provided dormitories for seventy nurses.

The Grocers’ Company’s Wing from the north side of Whitechapel Road. Photographed by Derek Kendall in 2016

A foundation stone was laid on 27 June 1874. Construction by Perry & Co. was complicated by the intended route of the East London Railway, set to curve beneath the north-east corner of the new wing. As a precautionary measure, the foundations nearest the railway line were excavated to a depth of thirty-five feet and filled with concrete. The outward appearance of the new wing matched the austerity of the Alexandra Wing, with plain brick elevations decorated by a string course and a dentil cornice of Portland stone. The tiled roof was punctuated by pedimented dormer windows that admitted light into the attic dormitories, and tall brick chimneys with oversailing tops and stone string courses. Two rear towers rose above the roofline of the wing, displaying louvered openings and steeply pitched roofs; one contained a water tank and the other was fitted with a ventilation shaft. There were fireproof floors. At street level, a wooden carriage shed built in 1876 occupied the narrow stretch between the north front of the new wing and Whitechapel Road.

The Grocers’ Company’s Wing was formally opened by Queen Victoria in March 1876, in a grand celebration reported to have lent ‘an attractive and joyous aspect to (an) ordinarily dull and dingy but busy quarter’. [2] In the following months, patients were gradually moved into the new wards, which were praised for their ‘light and pleasant aspect’. [3] The wards were fitted with specialised ventilation systems devised by T. Elsey and George Jennings. Two rows of evenly spaced beds extended across the long walls of each ward, facing inwards. This utilitarian arrangement was relieved by potted flowers and pictures on the walls amongst formal plaques bearing the name of each ward. At the time of writing (January 2017), the appearance and plan of the north range of the Grocers’ Company’s Wing had survived with only minor alterations, despite changes in room use. By the 1930s an operating theatre was located on the north side of the ground floor, lit by a large bay window overlooking Whitechapel Road. On the ground floor of the south range, wards were converted into isolation rooms. The X-Ray Department was housed in the basement of the north range and later extended to accommodate a suite of rooms, including several X-Ray rooms, dark rooms, a film store and offices. The building closed in 2012, when the hospital moved into its new premises.

References

[1] Royal London Hospital Archives & Museum (RLHA), RLHLH/A/5/35, pp. 58, 86, 110–1, 123, 208, 425, 439.

[2] ‘London: Saturday, March 11, 1876’, Illustrated London News, Issue 1911, p. 242.

[3] ‘The Queen’s Visit to Whitechapel, Reynolds’s Newspaper, Sunday 12 March 1876.

The Rise and Fall of the Adelphi

By the Survey of London, on 13 January 2017

Although little of it survives today, the Adam brothers’ innovative town-planning experiment at the Adelphi, off the Strand, of 1768–74, remains one of their best-known and admired works. Colin Thom of the Survey of London will give an evening talk on the theme of ‘The Rise and Fall of the Adelphi’ at Sir John Soane’s Museum on Monday 23 January 2017 – the first in a series of events to accompany the museum’s Robert Adam’s London exhibition. Here Colin provides a brief account of the Adelphi, which the Survey recorded at the time of its demolition in 1936. The results were published in Survey of London, volume 18, St. Martin-in-The-Fields II: the Strand (1937).

The Adelphi and the Thames riverside, looking east (engraving by Benedetto Pastorini, reproduced in the third (posthumous) volume of the Adam brothers’ Works in Architecture (1822)

The Adam brothers’ concept at the Adelphi is immediately striking for its monumentality and ambition. Here was an unprecedented attempt to create a large and entirely new district of elegant housing, raised up by some extraordinary engineering on a series of vaulted warehouses above the River Thames, on what had been an unfashionable, run-down stretch of ground known as Durham Yard.

Robert Adam’s genius lay in his ability to take and adapt elements of antique architecture and create from them something that was uniquely his own. At the Adelphi, his principal inspiration was the ruined palace of the Roman Emperor Diocletian at Spalato (modern-day Split, in Croatia), which he surveyed in 1755 as part of his Grand Tour and which formed the subject of a detailed monograph, published by Adam in 1764.

The remains of the sea front of Diocletian’s Palace at Split (engraving by Paolo Santini, Plate VII from Robert Adam’s Ruins of the Palace of the Emperor Diocletian at Spalatro in Dalmatia, 1764)

The similarities were evident. Both sites sloped down to the waterfront, hence both required embanking and the construction of vaults to create an even ground level above. The grouping of the long continuous frontage of the palace at Split along the shore, flanked by projecting towers at either end, is immediately recognizeable in Adam’s massing of the Adelphi blocks when seen from the river, with the central range of the best terraced houses – the Royal Terrace (later renamed Adelphi Terrace) – flanked by the ends of the lesser blocks of housing in the side streets leading to the Strand. In a characteristic Adam act of self-publicity most of the streets were named after the brothers – Adam Street, John Adam Street, Robert Street, &c.

Adam office design for the riverfront elevation of the Adelphi development (Sir John Soane’s Museum, Adam vol. 32/10), and elevations of the sea wall of Diocletian’s Palace (Plate VIII from Adam’s Ruins of the Palace of the Emperor Diocletian)

Robert Adam had been captivated by the transformation of the palace at Split into a bustling modern city, as well as by its Roman remains. This aspect he reinterpreted for London as a mixed environment of houses of several sizes and classes arranged in a grid of streets, along with shops, coffee houses, a tavern, hotel, Coutts’ bank, and a new Adam-designed headquarters for the Royal Society of Arts on John Adam Street – all underpinned by the cavernous wharves and warehouses. There was something undeniably Picturesque about the Piranesian sequence of dark vaults beneath the urbane streets of housing above.

The Adelphi vaults in 1936 (Historic England Archive photograph, AA65/00065)

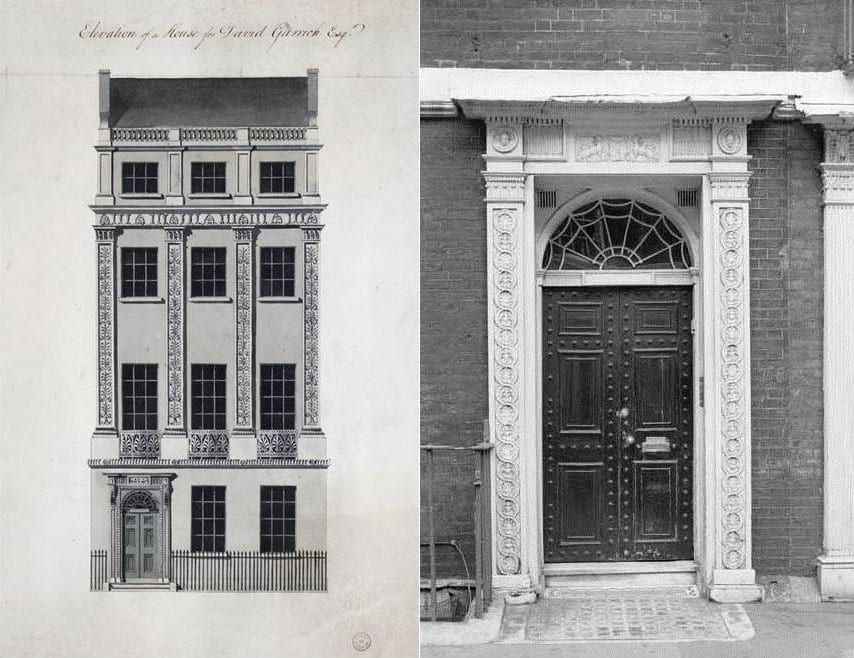

As originally built, the Adelphi houses showed the fine balance between ornament and plain surface at which Adam excelled, with relatively simple brick façades enlivened by ornamental stucco pilasters (emblazoned with honeysuckle motifs), entablatures, string courses, decorative doorcases and pretty iron balconies.

David Garrick’s House, Royal Terrace (Adam office elevation in Sir John Soane’s Museum, Adam vol. 42/60), and a typical Adelphi doorcase at No. 9 Adam Street (Historic England Archive photograph, AA65/06112)

Though built as a speculation, the houses were decorated inside in the distinctive ‘Adam style’ familiar from his bespoke country and town house commissions, with decorative plasterwork to the walls and ceilings, and carved chimneypieces. The house at the centre of the Royal Terrace, taken by the actor David Garrick, a friend of the Adams, was especially fine, with painted panels by Antonio Zucchi incorporated into its main drawing-room ceiling, and a staircase with attractive bronze balustrading.

Adam design for the front drawing-room ceiling in David Garrick’s house (Sir John Soane’s Museum, Adam vol. 13/30)

The Adelphi was begun at a time when Robert Adam’s star was in the ascendant. With a flourishing London practice and a succession of spectacular country house commissions behind him, he was Britain’s most fashionable architect; his Diocletian monograph had affirmed his status as a leading expert in the antique and in antique-derived Neoclassicism; and with his three brothers, John, James and William, he had recently established a London-based contracting and building supplies company – William Adam & Co. (which built the Adelphi) – echoing the family’s wide-ranging business interests in Scotland. But bold though the Adelphi was in its architecture and engineering, as a financial venture it was risky and impetuous, coming uncomfortably soon after the Adams had agreed with the Duke of Portland to build Portland Place on his estate at Marylebone – another ambitious town-planning commitment. They also had difficulty selling houses at their full valuation. Badly overstretched and with many properties unfinished, the Adams were forced to mortgage houses or sell them cheaply in order to raise capital to finish the development. Then a Scottish banking crash in the summer of 1772 tipped them to the verge of ruin. Though the sale of their assets by a private lottery saved them from bankruptcy, the brothers’ reputation had been tarnished, and they were never able to regain the heights of their earlier successes. The name Adelphi, chosen to immortalize the Adam ‘brotherhood’, also became a byword for over-reaching ambition.

The Adelphi survived in relatively good condition into the nineteenth century, though its immediate connection to the riverfront – such a fundamental element of the design – was lost when the Thames was pushed back and the Victoria Embankment and Gardens were created in front of it in 1864–70. Then in 1872, shortly after the lease had been renewed, heavy Victorian window dressings and a lumpy pediment were added to the Adelphi Terrace façade, disrupting its careful proportions. Also, by then the vaults beneath had become infamous as a haunt of the poor, the homeless and other outcasts of society.

Adelphi Terrace in the 1790s (from Thomas Malton’s A Picturesque Tour Through the Cities of London and Westminster, 1792–1801), and in 1901 (Bedford Lemere photograph in Historic England Archive, BL16618/001)

In 1927 the Adelphi estate was sold at auction, and in 1936 many of the houses, including the great riverfront terrace and its underground vaults, were torn down and a new Art Deco Adelphi building (designed by Collcutt & Hamp) erected in their place.

The remains of the demolished Adelphi Terrace, 1936, with buildings in John Adam Street beyond (Historic England Archive photograph, AA65/00065)

Today only a few runs of houses remain from the Adam development, in Robert Street, Adam Street and John Adam Street, including the beautifully proportioned Royal Society of Arts building, designed by Robert Adam.

Surviving houses in Adam Street, 2016 (Historic England photograph by Chris Redgrave) and Robert Adam’s pencil design for the elevation of the Royal Society of Arts building, John Adam Street (Sir John Soane’s Museum, Adam vol. 30/28)

Other fragments survive here and there, particularly in the Victoria and Albert Museum, including David Garrick’s front drawing-room ceiling, now incorporated into the British Galleries.

The ceiling from Garrick’s front drawing room in the V&A British Galleries. Photograph © Victoria and Albert Museum

You can read the Survey of London’s 1937 account of the Adelphi on British History Online here

East London Mail Centre and E1 Delivery Office, 180–206 Whitechapel Road

By the Survey of London, on 11 November 2016

The large concrete building which dominates the corner of Whitechapel Road and Cavell Street represents the last expression of postal activity on an extensive site which was once the centre of the Post Office’s operations in the East End. Before its closure in 2012, the East London Mail Centre (formerly known as the Eastern District Post Office) processed mail for the entire ‘E’ postal district, an area covering over 50 square miles from Chingford to Poplar, and was the eastern terminus of the Post Office Railway. During its 130-year association with the Post Office, the site has seen successive building projects prompted by rising workloads, technological developments and changing patterns of consumption.

East London Mail Centre, view from Cavell Street in 2016 (© Survey of London, Derek Kendall).

By the 1880s the Eastern District Office had outgrown its premises in Commercial Road and sought land for a chief office with room for expansion. It purchased a piece of former waste ground near the London Hospital, occupied by a paper-stainer’s shop and two cottages. With a 50ft frontage extending south from Whitechapel Road to Raven Row, the site was generous in size and its situation ideal. A new post office was built to designs by Henry Tanner of the Office of Works. It comprised a three-storey red-brick range with a public office fronting Whitechapel Road, and a single-storey sorting office at the rear. The main elevation of the public office was grand in character, with a central pedimented gable and round-arched windows on the third floor. In contrast, the sorting office presented a robust brick elevation to Cavell Street, with a plain staff entrance and large recessed windows.

Rapid growth in demand for postal services sparked plans to extend the building to relieve ‘cramped’ working conditions. By 1899 the number of letters processed at the Eastern District Office had increased twofold. Ground to the west of the building was acquired and a significant extension built to designs by Jasper Wager of the Office of Works, which nearly doubled the floor area. Further alterations followed with the construction of the Post Office Railway, or ‘Mail Rail’, to plans by William Slingo, engineer to the General Post Office, and Harley H. Dalrymple-Hay, consulting engineer. The underground electric railway was conceived in 1911 as a solution to the strain on London’s postal services caused by traffic congestion and a soaring volume of letters and parcels. It opened in 1927 to connect all of the capital’s major post offices, with its eastern terminus at Whitechapel. The line approached from Liverpool Street, following the route of Whitechapel Road before curving southwards to meet the station platform and terminating in a loop to the south of Raven Row. Although the railway was closed in 2003, the infrastructure survives and has attracted proposals for reuse.

Map of the Post Office Railway in 1937 (British Postal Museum and Archive catalogue)

East London Mail Centre, north elevation overlooking Whitechapel Road.

The introduction of mechanised postal sorting equipment in the 1930s led to new requirements for sorting offices and Whitechapel Road’s was probably considered unsuitable for modernisation. A scheme for redevelopment of the site seems to have been in place by 1956, when plans indicate that the adaptation of the former clothing factory on the east side of Cavell Street for post-office use was considered, most likely as an interim measure. The acquisition of Nos 180–188 Whitechapel Road and the adjacent builder’s works provided a substantial site with a frontage of over 200ft.

The earlier buildings were demolished and the present Modernist building constructed in two phases by 1970. The first phase comprised the eight-storey west block, which housed a ground-floor public post office with administrative offices above. It was followed by the adjoining four-storey sorting office, which extends along Cavell Street to Raven Row. The drab utilitarian exterior was the product of a short-lived initiative to standardise the design of post office buildings, in a new house style showcased in a 1960s exhibition produced by the architects’ department of the Ministry of Public Building and Works, headed by Eric Bedford. The main elevation facing Whitechapel Road is divided into eleven bays clad with prefabricated-concrete panels and horizontal bands of glazing. The structural frame of the building is exposed on the ground floor by four concrete columns flanking the van entrance to the sorting office. The widely publicised ‘modular system’ was contrived as a ‘common approach’ to building design to make post offices ‘instantly recognisable in any setting’.

Photograph of a model of the Eastern District Office (BPMA catalogue)

Van entrance to the former sorting office, flanked by open concrete shafts.

The interior of the sorting office was laid out for a mechanised workflow, which processed four million items each week. The ground floor functioned as a loading yard, with large entrances for postal vans opening onto Whitechapel Road and Raven Row. A warren of chutes and conveyors enabled the flow of letters, parcels and mail bags between stages in the sorting process. A chain conveyor brought inward mail bags from the yard to the sorting floors, to be processed by specialised machinery. The first, second and third floors of the sorting office comprised open-plan rooms with continuous steel-framed windows on each exterior wall to maximise light provision. Offices for inspectors were formed from light partitions. The Eastern District relied on over 2,000 postal staff working through the day and night, and a lounge, games room and bar were provided on the fourth floor.

Isometric plan of the basement, ground floor, first floor and mezzanine (BPMA catalogue)

Isometric plan of the second, third and fourth floors (BPMA catalogue)

The East London Mail Centre did not survive plans announced in 2000 to modernise London’s sorting system and, at the time of writing (2016), its former offices are occupied by tenants and only a modest delivery desk continues to operate. As the site has been earmarked for redevelopment by Tower Hamlets Council, the building is likely to be demolished.

The Survey of London has launched a participative website titled ‘Histories of Whitechapel’. Please visit at https://surveyoflondon.org.

White Church Lane, Whitechapel

By the Survey of London, on 21 October 2016

White Church Lane is a last redoubt of Whitechapel’s rag trade, still (or until very recently – it’s hard to be up-to-the-minute) sporting shopfronts pertaining to manufacturers and wholesalers: Tip Top Casual Wear, K. K. Hosiery Ltd, Raw Blue Ltd, N.E.W.S. Urban, Mekyle (Bayfield Trading Ltd), Denim World, Alish (wholesale jewellery and accessories), HIP HOP Collections (wholesalers of American street wear), Senior Style Ltd, Abraham Posh Lady London. There is also an efflorescence of street art, work from 2012 facilitated by Global Street Art’s negotiations with property owners.

The road’s origins are as the north end of Church Lane, the only north-south route through the parish, in existence by the seventeenth century to link Well Close to Whitechapel High Street. The northern stretch may not have been much built up until the 1660s and back building suggests density and low status – Church Rents or Maidenhead Court (later Dyer’s Yard), and Hatchet Alley (later Spectacle Alley, now Whitechurch Passage) which had Adam and Eve Court on its south side, and there was Back Yard off the lane’s west side. All this had gone by 1800. Eighteenth-century property holders included Joel Johnson, the carpenter and architect who worked on local churches and the London Hospital. There was a sugar house near the north end and the Fir Tree public house was at the south end of the east side, adjacent to a site taken in the 1840s for John Furze’s St George’s Brewery (subsequently Johnny Walker’s St George’s Bond, now Hult International Business School). The north end of Church Lane’s east side was redeveloped in the early 1850s and the south end was obliterated by extension of the Commercial Road in 1869–70. Redevelopment since has been piecemeal, with a central section of the east side replaced in 2000-2 by the Naylor West flats, designed by Michael Squire and Partners for Ballymore Properties. That block’s artless greyness was a herald of cleansing, and sites at the street’s south end on both sides are now destined to host tower-block flats.

4-8 White Church Lane, buildings of the 1850s with painted shutters of 2012 (© Derek Kendall, 2016).

The north end of the street’s east side is anchored by what was St Mary’s Clergy House, now a Japanese restaurant, a building of 1894–5, Herbert O. Ellis, architect, that was an adjunct to the parish church that stood on the site of Altab Ali Park (see blog post of 15 April 2016). Next door, No. 4 of 1852–3 was built to be a sale room for Isaac Bird, auctioneer. Hunto has painted its shutter. A workshop behind an entrance passage at No. 4A was built in 1899–1900 for William Nay, a mirror manufacturer, and converted to be a necktie factory in the 1920s. The front-door shutter has a figure by Tizer. Next door at No. 6 the shutter art is by 2Rise, whose tag has also been prominent on the south side of Whitechurch Passage. Nos 8 and 10 were built in 1852 by Jabez Single of New Road, houses with shops first occupied by Mark Berry, a zinc and tinplate worker, and James Fullerton Barber, a printer. Alterations and extensions to the rear were made for a bedding factory that was later a silk-screen and joiners’ workshop. Dining rooms at No. 12, run by Alfonso Pappalardo in the 1930s, were held from the early 1940s to the early 1950s by Narian Singh for one of the area’s first Asian-run restaurants. At the time Bonn & Co Ltd had a large biscuit warehouse behind Nos 16–32.

Solomon Kirstein’s letterhead, showing 29 Commercial Road (Tower Hamlets Local History Library and Archives, Building Control file 41978) and Kirstein Mansions, 34-40 White Church Lane, shops, tenements and workrooms of 1911 built for Solomon Kirstein (© Derek Kendall, 2016).

A house and shop at No. 34 were the premises of Henry Bear, a tobacco manufacturer here from the 1840s to the 1880s. He acquired the freehold of the buildings on the sites of Nos 34–40 and an empty site at 29–31A Commercial Road and in 1901 a lease was transferred to Solomon Kirstein, a printer based at No. 38. By 1902 Kirstein had built three three-storey houses or workrooms with shops at Nos 29–31A, with Herbert O. Ellis as his architect. Kirstein took the shop at No. 29, living above with his wife, three children and a servant. It was not until 1911 that Kirstein redeveloped his Church Lane frontage as Kirstein Mansions, shops, tenements and upper-storey workrooms, this time with John Hamilton & Son, architects. Around 1970 David Abraham began selling knitwear at No. 34. In 2015 the David Abraham Partnership put forward a redevelopment scheme for the whole site proposing a seventeen-storey tower designed by Stock Woolstencroft.

3 White Church Lane, with embellishments of 2012 (© Derek Kendall, 2016).

On White Church Lane’s west side a small bomb-damage replacement building of c.1960 at No. 3 was decorated in 2012. The entrance-door shutter has wings by Probs, and the south return to Whitechurch Passage a head by Hunto and ‘The Lady’, a low-relief ceramic by ChinaGirl Tile.

‘The Lady’, by ChinaGirl Tile (© Derek Kendall, 2016).

Further south, first-floor blind arcading in a little-altered stock brick front at No. 17 was built around 1840 for Charles Marshall, a veterinary surgeon who probably dealt largely with horses. The shop is infill of what was an open carriageway into the twentieth century. Stables to the rear were rebuilt for Marshall’s successors. Around 1880 Simon Cohen, a pastry cook based at No. 32 across the road, established a refuge for homeless immigrant Jews in a house at No. 19. Named the Poor Jews’ Temporary Shelter, its closure as insanitary in 1885 led to fundraising that permitted the establishment of better premises on Leman Street. Other properties continued to be used as ad hoc refuges or lodging houses. In late 1885 a Shelter employee took five immigrants from Brest-Litovsk to 11 Church Lane, then occupied by Paul Meczyk, a printer, only for them to be turned out on to the street. By 1891, in which year he fell out with the Shelter Committee, Cohen had converted the house at No. 19 to be a ‘Beth Hamedresh’ (Study Circle and Synagogue). He acted as his own builder and carried out further works in 1895–6. But this did not last. In 1898–9 Jacob King redeveloped the site with 9 Manningtree (formerly Colchester) Street; Arthur C. Payne was his architect. On the corner (No. 21) there was a Horse and Groom pub by 1760. The two-storey pub that had been run by Henry Levy was rebuilt for King in 1902 to designs by Ralph J. Miller, architect. It was a Truman, Hanbury & Buxton pub by 1910.

19-37 White Church Lane and 27 Commercial Road, demolished 2016 (© Derek Kendall, 2016).

Fishel K. Abrahamson converted a house at No. 29 to be a synagogue in 1895–6, and nineteenth-century houses at Nos 35–37 were part rebuilt and perhaps refronted in 1915. The four-storey corner warehouse that was 27 Commercial Road had been built in 1872–3 and more warehousing went up to its west in 1876–8 at No. 27A which accommodated Hyam Goldstein’s cap factory, then Aaram Bagel’s boot factory, Burstein Isaac & Co.’s cigarette factory, and tea packing. Nos 29–33 Church Lane and 27A Commercial Road were redeveloped in 1936–7, with George Coles as architect for M. Freedman, a gown manufacturer. Coles is best known as a cinema architect, and there was a faint echo of his Art Deco skills in the façade fenestration of the factory and showroom block. Shutter painting of 2012 here was by Malarky, Chase and Billy. A scheme for redevelopment of Nos 29–37 and 27–27A Commercial Road was prepared in 2012, approved in 2014 and refined in 2016 prior to clearance of the whole site, now complete. Plans initiated by Reef Estates Aldgate Ltd propose a 270-bedroom hotel in a 21-storey tower to be operated by Motel One, a German firm. The architects are Stock Woolstencroft.

The Survey of London has launched a participative website titled ‘Histories of Whitechapel’. Please visit at https://surveyoflondon.org.

Histories of Whitechapel

By the Survey of London, on 30 September 2016

The Survey of London has launched a participative website titled ‘Histories of Whitechapel’. Please visit at https://surveyoflondon.org.

We are inviting anyone with an interest in or experiences of Whitechapel’s rich history to contribute anything from research to memories, sketches to film clips. Visitors can explore an interactive map of the area and click on any building to discover or contribute more. The website will be active and evolving until the end of 2018 and will include the Survey’s own work in progress. It will continue in static form thereafter and the reservoir of material on Whitechapel will be edited to make volume 54 in the Survey’s main series of books.

To help to get the website off to a lively start we commissioned some illustrations of kinds not heretofore typical of the Survey of London, to evoke aspects of the character of Whitechapel. Judit Ferencz has given us some delightful illustrations based on observed outdoor life and Rehan Jamil has photographed some local domestic interiors to depict ordinary people in their homes.

We hope you enjoy their work. Please do have a look at the website. New contributions will be very welcome.

Altab Ali Park, illustrated by Judit Ferencz. Please click here to view Altab Ali Park on the ‘Histories of Whitechapel’ website.

Rehan Jamil, photographer.

Altab Ali Park, illustrated by Judit Ferencz.

Rehan Jamil, photographer.

Whitechapel Market, illustrated by Judit Ferencz. Please click here to view Whitechapel Market on the ‘Histories of Whitechapel’ website; new contributions are very welcome.

Rehan Jamil, photographer.

Peabody Estate, illustrated by Judit Ferencz. Please click here to view the Peabody Estate on the ‘Histories of Whitechapel’ website.

Rehan Jamil, photographer.

Whitechapel Market, illustrated by Judit Ferencz

Rehan Jamil, photographer.

37 Harley Street

By the Survey of London, on 9 September 2016

37 Harley Street, Marylebone (photographed by Chris Redgrave © Historic England).

Perhaps one of the most widely admired late-nineteenth century buildings in South East Marylebone is 37 Harley Street, built in 1897-9 to designs by Arthur Beresford Pite. It is remarkably different from the houses and flats around it, and when newly built the architectural press proclaimed it to be ‘nothing short of a revolution in Harley Street architecture’.

37 Harley Street, Marylebone, detail of oriel window (photographed by Chris Redgrave © Historic England).

Marylebone was once the heartland of Beresford Pite’s London buildings, and his office was just around the corner at No.48 where he added turquoise mosaic tiles to the ground-floor front. Many of his Marylebone buildings have gone, although his earlier 82 Mortimer Street survives, with its still arresting sculptural window treatment. At both houses Pite was working with a local building firm, Matthews Brothers. But while the Mortimer Street house was built with a specific client in mind, the anaesthetist Dudley Buxton, this one in Harley Street was a speculation. This was a boom time for medicine in the area, when houses were being snapped up by physicians and surgeons as homes with consulting rooms, and so it was designed with that end in mind.

37 Harley Street, Marylebone, detail of bay window (photographed by Chris Redgrave © Historic England).

The Georgian house that formerly stood at this corner was narrow and relatively small, without back yard or mews. By shifting the main entrance from Harley to Queen Anne Street (without altering the address) Pite created a more open and versatile layout within. But the real charm of the building is on the outside, in the use of warm Bath stone, a rarity hereabouts, and the harmonious integration of the architectural sculpture that adorns it. It is not bold and thrusting, as in the Mortimer Street figures, but sinuous and restrained.

37 Harley Street, Marylebone, detail of bas-relief panel by Schenck depicting anatomy (photographed by Chris Redgrave © Historic England).

The success of the sculptural element can be ascribed at least in part to the close collaboration between architect and carver. The many bas-relief panels of allegorical figures are the work of the architectural sculptor Frederick E. E. Schenck. Low-relief friezes on the bay windows are arranged with figurative subjects, flanked by flowing branches and leaves, representing Grammar, Astronomy, Justice and Philosophy, with Poetry represented by Homer. A dramatic winged figure atop the oriel symbolises Fame.

37 Harley Street, Marylebone, detail of Schenck panels on the oriel window (photographed by Chris Redgrave © Historic England).

The first occupants in 1901 were (Sir) Edward E. Cooper, an underwriter (later deputy chairman) at Lloyds, talented amateur singer, chairman of the Royal Academy of Music and future Lord Mayor, and his wife (Lady) Leonora.

37 Harley Street, Marylebone, detail of the iron railings (photographed by Chris Redgrave © Historic England).

The Coopers later moved out to Hampshire and by 1905 the surgeons Edred Moss Corner and (Sir) Percy William George Sargent were both practising and resident here; Corner’s son, the botanist Edred John Henry Corner (d. 1966) was born at No. 37 in January 1906. Other medical men associated with the building included the surgeons Sir Henry John Gauvain and Sir James Cantlie, both in the 1920s.

37 Harley Street, Marylebone, detail of coloured glass in the circular window in the door (photographed by Chris Redgrave © Historic England).

Though now subdivided and in mixed residential and office use, the building retains much of its original character.

37 Harley Street, Marylebone, first-floor landing with Pite-designed stair balustrade and coloured glass in landing window (photographed by Chris Redgrave © Historic England).

Text taken largely from the draft chapter from the forthcoming South East Marylebone volumes, which can be found online here.

Cavendish Square 5: the Duke of Cumberland’s statue

By the Survey of London, on 19 August 2016

This is the fifth instalment in an occasional series of posts about Cavendish Square. John Stewart’s Critical Observations on the Buildings and Improvements of London (1771) said of Cavendish Square that ‘the apparent intention here was to excite pastoral ideas in the mind; and this is endeavoured to be effected by cooping up a few frightened sheep within a wooden pailing; which, were it not for their sooty fleeces and meagre carcases, would be more apt to give the idea of a butcher’s pen’. This was a satirical allusion to the square’s new statue of the Duke of Cumberland, the ‘Butcher of Culloden’, commander at that final and decisive defeat of the Jacobite rising in 1746. All the same, the square was indeed let to a butcher for grazing.

John Stewart’s Critical Observations, 1771.

The gilt lead equestrian statue of the Duke of Cumberland had been erected in 1770 at the cost of Lt. Gen. William Strode, who had fought under and befriended the Duke, and whose own memorial in Westminster Abbey records him as ‘a strenuous assertor of Civil and Religious Liberty’. At the time Strode lived on Harley Street, on the north-east corner with Queen Anne Street. The Duke’s sister Amelia, who had paid for a lead statue of George III for Berkeley Square in 1766, lived at the west end of the north side of Cavendish Square. Strode conceived what was London’s first outdoor statue of a soldier in 1769, the same year he was alleged to have withheld clothing from his soldiers, a charge of which he was acquitted at a court martial in 1772.

J. P. Malcolm’s engraving of 1808 (© City of Westminster Archives Centre).

The statue was by John Cheere, who had made another version of Cumberland for Dublin in 1746. The paunchy figure in modern dress faced north to the contemporary temple fronts of what are now 11–14 Cavendish Square (see earlier post). That the statue faced this way, presenting its rear to those who approached the square along the Hanover Square axis, may reflect where Princess Amelia and Strode lived. It also looked to Scotland. The statue was immediately ridiculed on aesthetic grounds; any politics in the gesture appear to have passed without published comment.

Meekyoung Shin’s soap statue, photographed in 2013.

Lacking admirers, the statue fell into dilapidation. In 1868 the 5th Duke of Portland took it down, ostensibly to be recast. It never was, perhaps simply melted down instead. Its Portland stone plinth survived, with Strode’s inscribed dedication. By 1916 this had been encircled by a roof on thin columns to create a summer house. That lasted into the 1970s.

Meekyoung Shin’s soap statue in 2014 (© Historic England, Chris Redgrave).

In 2012 a replica of the lost statue was mounted on the plinth, made of soap on a steel armature by the Korean artist Meekyoung Shin as Written in Soap: A Plinth Project. She anticipated its gradual and scented erosion within a year, but its tenure was extended, her commentary on mutable monumentality complicated by endurance and popularity. An identical replica was installed at the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art in Gwacheon, South Korea, in July 2013. The Cavendish Square statue was dismantled in 2016.

Meekyoung Shin’s soap statue in 2015 (above and below).

RIBA headquarters, Nos 66–68 Portland Place

By the Survey of London, on 29 July 2016

RIBA Headquarters, view from the south-west (© Historic England, Chris Redgrave).

Ian Nairn once noted the irony that the RIBA’s headquarters should be located in Portland Place: the one street in London he felt had been ‘most stupidly and selfishly and blindly ruined by twentieth-century R.I.B.A. members’. But George Grey Wornum’s building, with its sophisticated union of clean lines and classical proportions, is not one of those brutal transgressors.

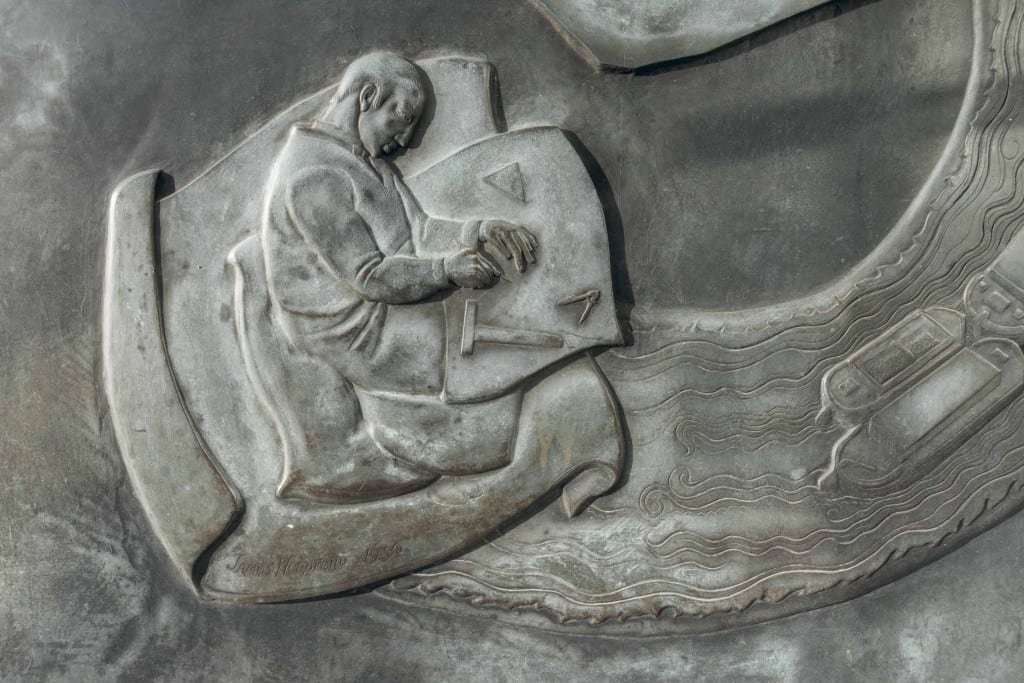

At the entrance, a pair of giant cast-bronze entrance doors, decorated with a series of charming relief sculptures, tell the story of London’s river and its buildings, modelled by James Woodford, to drawings prepared by J. D. M. Harvey.

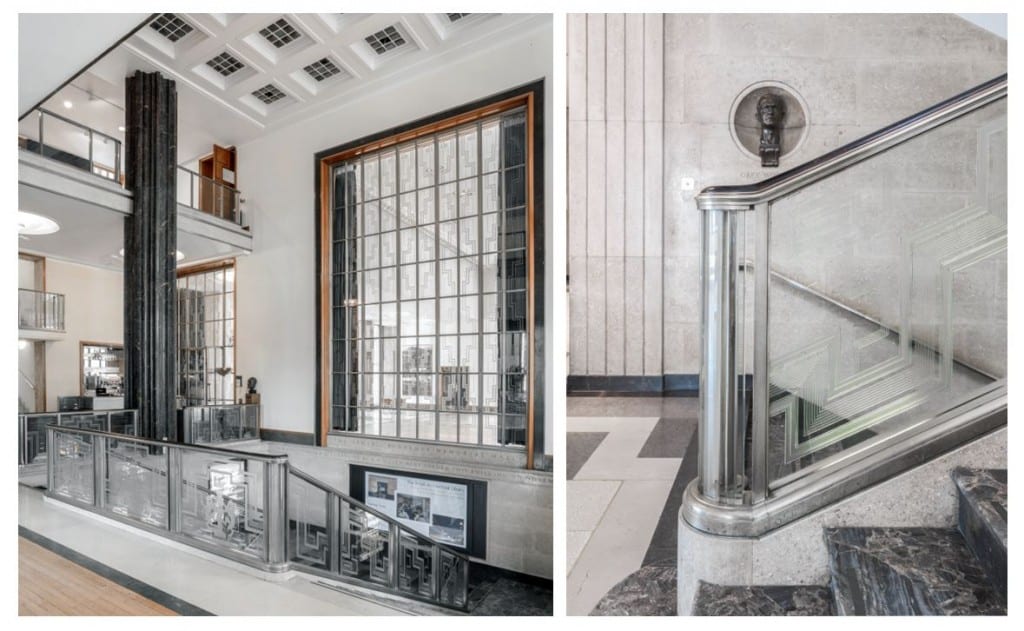

Inside, the entrance hall has a honey-coloured sheen from its yellow terrazzo floor slabs and polished limestone walls, incised with the names of RIBA Presidents and Gold Medallists. But it is the staircase that is Wornum’s tour de force. It is a dramatic space, dominated and held together by four giant fluted columns of green Ashburton marble, star-shaped in plan and without bases or capitals, that rise nearly 30ft to the coffered glass ceiling.

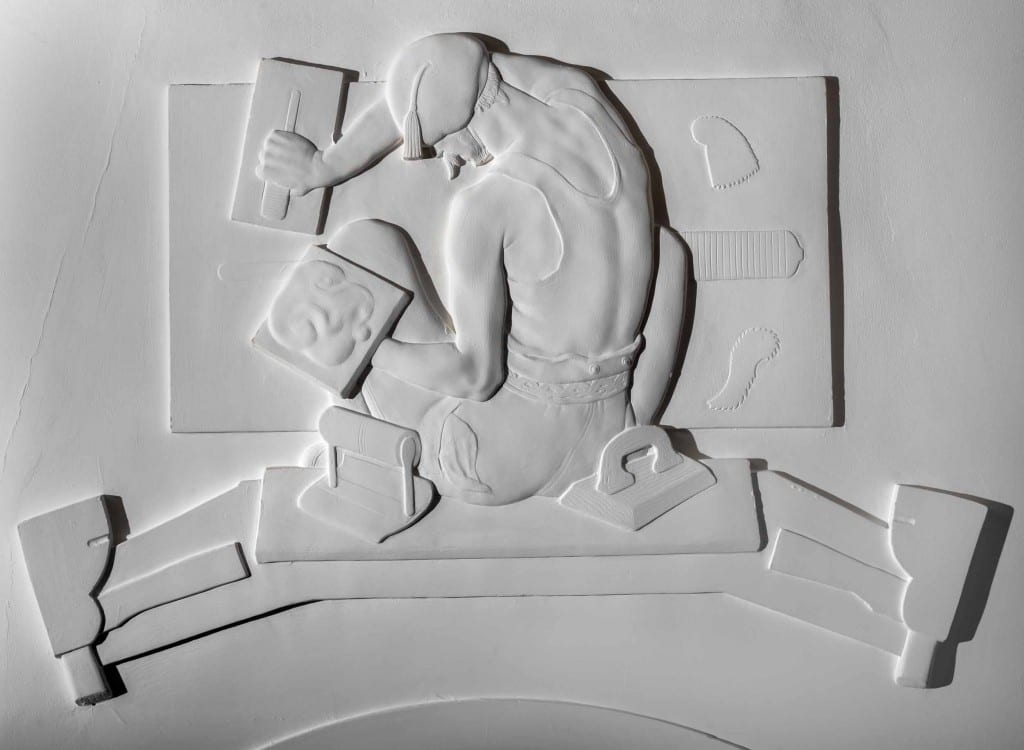

On the first floor is the principal reception room: the Henry Florence Memorial Hall. Decoration is everywhere, with a patterned floor and splayed limestone piers carved with scenes of architecture through the ages (designed by Edward Bainbridge Copnall), and several fine wall carvings (also by Copnall), including one showing Wornum and Maurice Webb deep in conversation under the watchful eye of Ragnar Östberg. On the ceiling are sculptures by Woodford depicting the various building trades. Also in this room is a pine screen carved with twenty reliefs (by Denis Dunlop) representing culture and industry in India, Canada, South Africa, Australia and New Zealand.

Henry Florence Memorial Hall, designed by Wornum with his visit to Stockholm obviously very fresh in his mind (© Historic England, Chris Redgrave).

Henry Florence Memorial Hall, ceiling panel by Woodford (© Historic England, Chris Redgrave).

Henry Florence Memorial Hall, splayed limestone piers carved with scenes of architecture through the ages (© Historic England, Chris Redgrave).

The British Architectural Library on the third floor was designed by Wornum in consultation with the RIBA’s then librarian Bobby Carter, with Moderne curved ends to its bookcases, and originally with a colour scheme by his wife Miriam (recently restored) of steel bookshelves enamelled in blue and yellow, and a brown cork floor.

British Architectural Library (© Historic England, Chris Redgrave).

With grateful thanks to Eloise Sinclair who put this blog piece together based on the text in the draft chapter from the South-East Marylebone volumes, which can be found here.

Close

Close