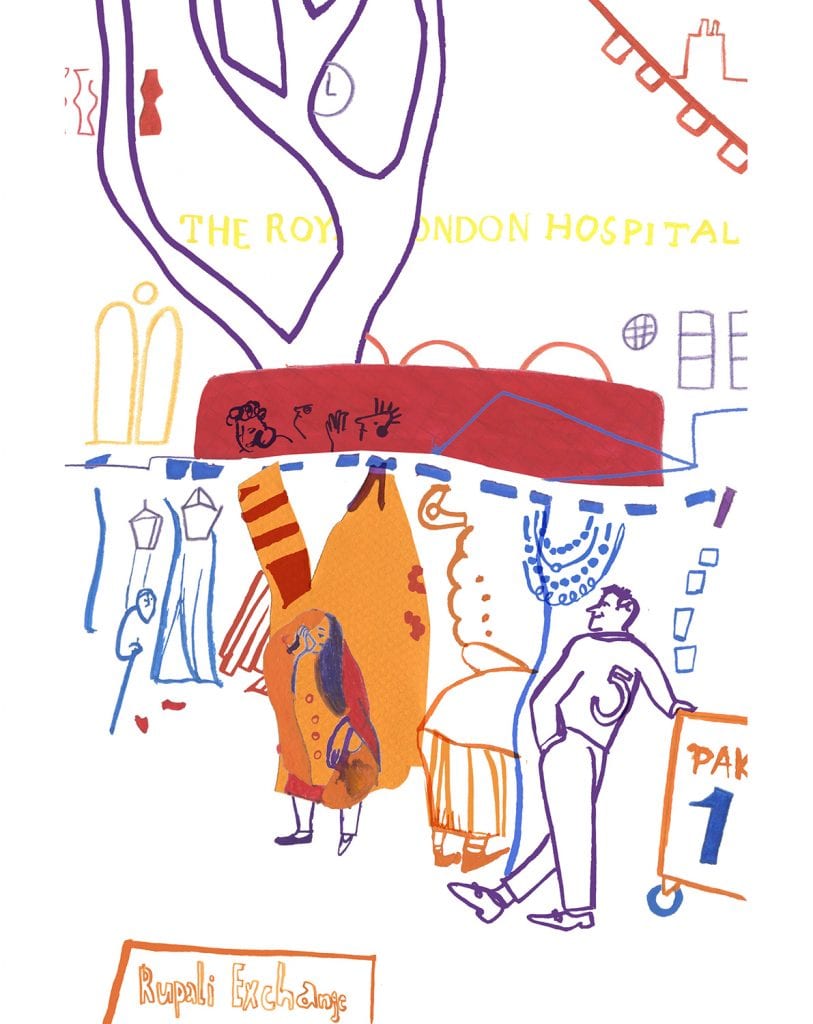

On 4 May 1978 Altab Ali, a 25-year old clothing machinist of Bangladeshi origin, was murdered in Adler Street, Whitechapel, beside the park that was then called St Mary’s Gardens, a name that recalled the Church of St Mary Matfelon (the medieval ‘white chapel’) which had stood on the site until 1952.

Altab Ali Park was named in 1994 in memory of a young man murdered near by in 1978 in a racist attack (© Jim Linwood, photo reproduced without changes under a Creative Commons attribution licence). If you are having problems viewing images, please click here.

This attack galvanized resistance to racism in the area and beyond. A decade on, Tower Hamlets Council commissioned David Petersen, an artist–blacksmith, to make the park’s wrought-iron gateway arch to commemorate victims of racist violence. Put up in 1989 at the park’s Whitechurch Lane corner, it playfully combines Bangladeshi and Gothic ornamental motifs. Following a local campaign, the Council renamed the gardens Altab Ali Park in 1994. Five years later the south-west corner of the park gained a Shaheed Minar (Martyrs’ Monument), a semi-circular concrete plinth with five white steel screens, representing a mother and children, the former to the centre bow-headed in front of a blood-red circle. This is a smaller version of a Shaheed Minar in Dhaka, Bangladesh, designed by Hamidur Rahman, which commemorates activists of the Bengali language movement killed in 1952. Long desired and petitioned for, a Whitechapel monument began to be planned in earnest in 1996, though not at first with this site in mind. The Bangladesh Welfare Association marshalled contributions from 54 organisations and worked closely with the Council. Another copy of the Dhaka monument was made in Oldham in 1996–7. Its designers, the Free Form Arts Trust, were brought in and commissioned to make Whitechapel’s structure larger. Landscaping and the plinth were handled by the Council, and Arts Fabrications made the monument. It was unveiled on 17 February 1999 by Humayun Rashid Choudhury, Speaker of the Bangladeshi Parliament.

The Shaheed Minar (Martyrs’ Monument) was erected in 1999 as a smaller replica of a memorial to nationalist student activists in Dhaka, Bangladesh (© Historic England, Lucy Millson-Watkins, photographer).

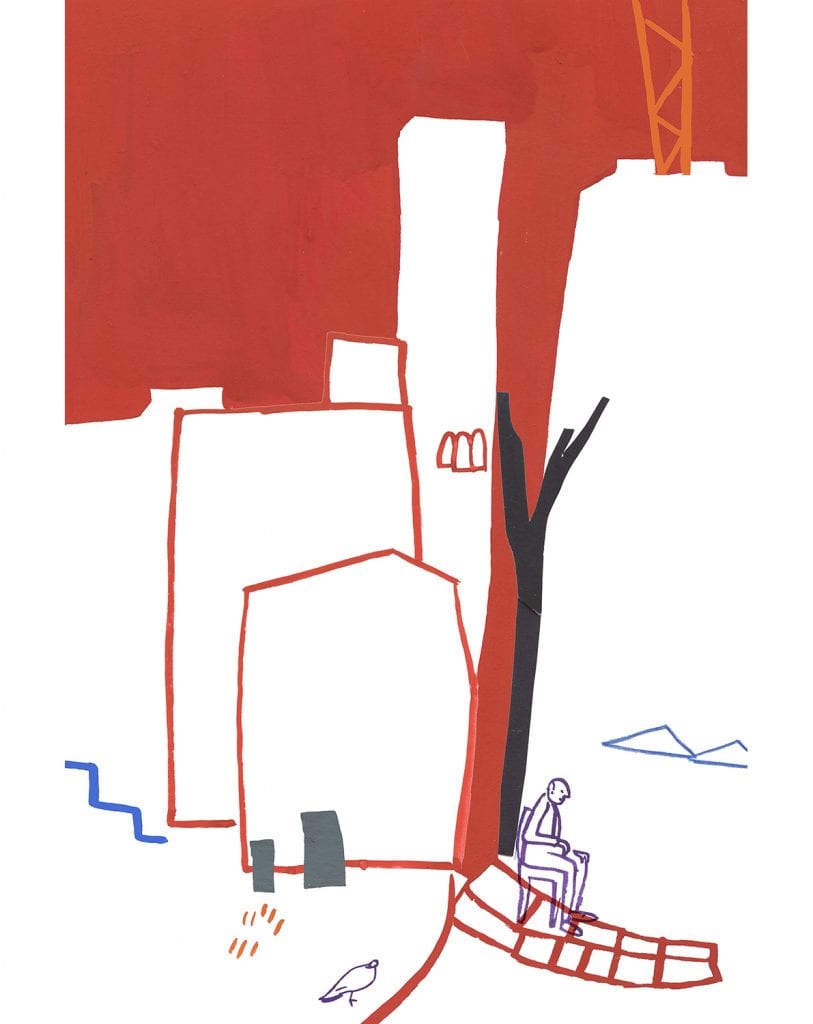

Further landscaping followed in 2002 with a new diagonal path through the churchyard that bore an inscription of part of a poem by Rabindranath Tagore, ‘The shade of my tree is offered to those who come and go fleetingly’. The lettering disappeared when another relandscaping of Altab Ali Park was undertaken in 2011. The layout that followed was designed by muf architecture/art as ‘a matrix of the religious and the secular’, [1] and celebrated as ‘a grand collage’. [2] It includes a raised green terrazzo walkway and bench that marks parts of the outline of the site’s Victorian church. Stone fragments carved by apprentices at the Building Crafts College were scattered to suggest the lines of the preceding church. Further south, hillocks, boulders and tree stumps articulate the land east of the Shaheed Minar and, with a small platform, open up a longer view of the monument.

Whitechapel’s churchyard, which has its origins in the thirteenth century, had been walled round and made more or less co-extensive with the present-day park by the 1720s – the eastern part was occupied by a rectory and its private garden. Notable burials in the churchyard included those of Richard Brandon in 1649, said to have been the executioner of Charles I, and Sir John Cass in 1718. The burial ground came to be badly overcrowded and in 1846 its appearance was said to be ‘very far from creditable to the parish’. [3] It was planted with trees and shrubs in 1850–1 under the supervision of Samuel Curtis (who had landscaped Victoria Park), and burials ceased in 1854. A record from 1875 lists 87 gravestones and monumental slabs in the churchyard. These have since been largely removed or tidied to the site’s edges, a notable exception being a chest tomb for the Maddock family (local timber merchants), a stout early nineteenth-century monument of Portland stone with a marble armorial panel. This remains in place in what was the south-east part of the churchyard.

The Maddock family’s late-Georgian chest tomb is a reminder that the site was a churchyard (© Survey of London).

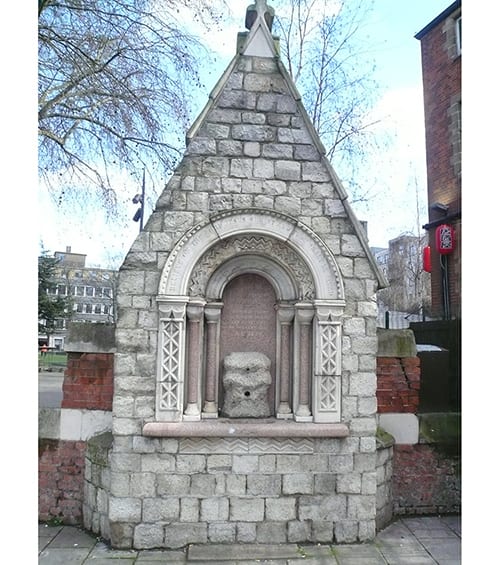

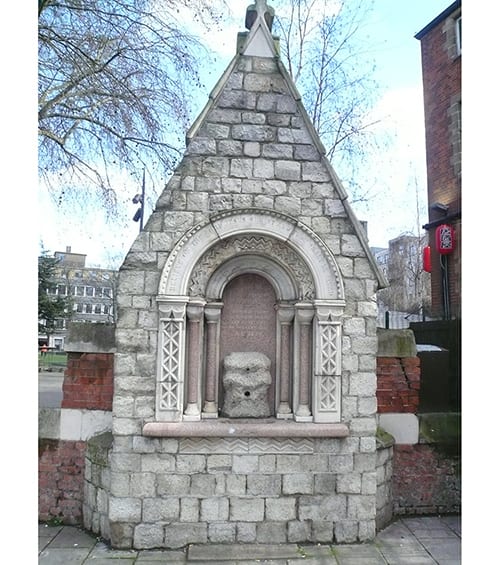

The drinking fountain that now faces Whitechurch Lane was originally on the Whitechapel Road, put up in 1860 ‘from one unknown yet well known’, as it is inscribed, perhaps a reference to the Rev. William Weldon Champneys, Whitechapel’s long-serving and reforming rector who left the parish in that year. Early for a public drinking fountain, it has a Norman arch with pink granite colonettes and back panel set in a gabled ragstone surround. The form of the central motif closely followed the example of London’s first free drinking fountain, put up at Snow Hill in 1859 to great public acclaim. The larger Whitechapel fountain was moved round to Church Lane in 1879, then in 1894 moved again a bit further north to make way for the red-brick building at 2 Whitechurch Lane, formerly St Mary’s house, which was built to house the parish clergy, and now houses a Japanese restaurant. A K2 telephone kiosk was placed to the fountain’s right around 1927 and a K6 kiosk followed in the 1930s. The former remains in place.

Whitechapel’s drinking fountain of 1860, moved here later in the nineteenth century (© Survey of London).

Rebuilding of the church in the 1870s presented an opportunity to widen the adjacent stretch of Whitechapel Road, so in 1878 a (still existing) stone-coped red-brick boundary wall went up along a new setback line. It was designed by the church’s architect, Ernest C. Lee, using Suffolk bricks identical to those he had used to face the church. Two former entrances from the Whitechapel Road are now blocked, the larger one still marked by remnants of stone steps.

When the churchyard wall was built it was proposed that tombstones and human remains should be moved to allow part of the grounds to be an ‘ornamental garden’. [4] This objective was achieved in 1885 when the Metropolitan Public Gardens Association assisted in opening the churchyard to the general public as gardens with an improved layout, seats and a caretaker. There was an entrance charge of a penny. But public use was not sustained and in 1938 proposals for reviving the public garden were blocked by the Rev. John A. Mayo who was concerned that the churchyard would ‘become the resort of undesirable characters’. [5]

The church and rectory were bombed out in 1940. Once the ruins had been cleared, and with the unfenced land indeed attracting uses that aroused criticism, the London County Council set out in 1957 to buy the churchyard to be a public open space, preparing a scheme for planting and landscaping. Legal delays as to title meant that it was 1966 before St Mary’s Gardens could be opened. The lines of the seventeenth-century church were set out in concrete blocks flush with the ground. First intentions had been to mark the medieval ‘white chapel’, but without funding for archaeology this proved impossible. Future posts will describe the history of the church.

On 4 May 2016, Tower Hamlets Council launched Altab Ali Commemoration Day as an annual event.

The park in 2011 when blocks delineated the location of the seventeenth-century church of St. Mary Matfelon (© Historic England).

References

[1] Building Design, 11 March 2011, p.4

[2] London Evening Standard, 16 Nov. 2011

[3] The Builder, 15 Aug 1846, p.388

[4] The Builder, 3 Aug. 1878, p.812

[5] East London Observer, 3 June 1939

Close

Close