Looking for a lost painting of an Oxford Street chemist’s workshop by W. H. Hunt

By the Survey of London, on 4 May 2018

Can anyone help the Survey of London trace a remarkable lost watercolour of the chemist Jacob Bell’s workshop in Oxford Street by the famous early Victorian painter William Henry Hunt? Today the painting seems to be known only from a splendid print. But the original was in the library of the Chemists’ Club of New York in the 1930s, so the likelihood is that it is still somewhere in the United States.

John Simmons and his apprentice working in the laboratory of John Bell’s pharmacy in Oxford Street. Engraving by J. G. Murray, 1842, after W. H. Hunt. Credit: Wellcome Collection. CC BY.

W. H. Hunt (1790–1864), sometimes known as ‘Birds Nest’ Hunt to distinguish him from his later contemporary William Holman Hunt, was among the finest and most delicate of English watercolour painters. Nearly all his works show intimate rural scenes, or close-up details from nature, among which his studies of bird’s nests and fruits are outstanding. He very seldom painted large or urban compositions – which makes his study of Bell’s workshop, originally entitled A Laboratory, the more intriguing.

The story behind the painting appears to be as follows. Jacob Bell (1810–59) was the son and successor to John Bell, a chemist who founded a firm in Oxford Street still in existence today as John Bell & Croyden in Wigmore Street. Jacob was a man of wide interests and initiatives, in politics, art, photography and, above all, the better organization of his profession. He was effectively the founder of the Royal Pharmaceutical Society. That took place in 1841, the very year in which A Laboratory was painted. It shows the workshop behind Bell’s shop, with John Simmonds, Bell’s apothecary and one of his father’s early apprentices, seated on a barrel stirring a crucible, while an apprentice boy, William, cleans a mortar. It seems a reasonable guess to suppose that the painting and the founding of the society are connected, and that Jacob Bell wanted to commemorate the charming but rather primitive state of the chemists’ premises at the time, before they were modernized.

Jacob Bell had had some art-training himself and enjoyed many friends among artists, principally Edwin Landseer. So it is likely that he knew Hunt well, and asked him to paint the picture as a special favour. It was exhibited at the Society of Watercolour Painters’ annual exhibition in 1841, and then again at the Manchester Art Treasures Exhibition of 1857, when it was lent by Jacob Bell. After Bell’s death the painting disappeared from view. Much later, in 1931, it was spotted on the walls of the library in the Chemists’ Club of New York and cleverly identified by an American scholar, Elsie Woodward Kassner. It was known to be English, and had been anecdotally known in the club as Michael Faraday washing apparatus for Sir Humphry Davy. Kassner wrote an article for the Journal of the American Pharmaceutical Association (Volume 20, number 3) correctly identifying the subject.

That ought to have been that. But unfortunately the premises and holdings of the Chemists’ Club were sold in the 1980s and ‘90s. Some items went to the Chemical Heritage Foundation in Philadelphia, but the Hunt painting was not among them, and efforts to trace this unique work of art have so far proved unavailing. Fortunately we have a fine lithographic print of it by J. G. Murray, published in 1842, but to find and republish the original would be thrilling.

Whitechapel pubs (and a brewery)

By the Survey of London, on 13 April 2018

As part of the Survey of London’s ‘Histories of Whitechapel’ project and for eventual publication in our Whitechapel volumes, Derek Kendall has been photographing the area. Lately, through the winter months, he has been concentrating his attention on pubs. These recent photographs illustrate a range of interiors and exteriors, some of better-known pubs and others less well known.

The Princess of Prussia Public House, 15 Prescot Street. Built in 1913 and a good example of an attractively legible Trumans façade. (© Derek Kendall)

Bar Indo, 133 Whitechapel Road. Built in 1854 as The Blue Anchor Public House after its predecessor was destroyed in a fire. Until the 1760s the pub on this site was called the David and Harp. (© Derek Kendall)

Interior of Bar Indo, 133 Whitechapel Road, recast with the front window in 1928 for Charringtons. The Blue Anchor sign is in storage above the entrance lobby. (© Derek Kendall)

View of bar with owners Peter and Katy Clarke. Bar Indo, 133 Whitechapel Road. (© Derek Kendall)

The Blind Beggar Public House, 337 Whitechapel Road. A Tudor ballad about Henry de Montfort, who died in the Battle of Evesham in 1265, imagined that he survived blinded to be rescued by a woman from Bethnal Green, where he ended his days begging. That parish once hosted other pubs of the same name. This establishment’s origins seem to be late seventeenth century. The present building dates from 1894 when it was erected to designs by Robert Spence, the engineer and architect to Mann, Crossman & Paulin. (© Derek Kendall)

The Blind Beggar, 337 Whitechapel Road. The blood-red ceilinged interior has been much remodelled. Latter-day notoriety turns around this pub being the site of the shooting of Georgie Cornell by Ronnie Kray in 1966. (© Derek Kendall)

Exterior of The White Swan Public House, Alie Street, Whitechapel. Originally built in the early nineteenth century, this pub’s fabric has undergone substantial changes since then. (© Derek Kendall)

The Brown Bear Public House, 139 Leman Street. This pub was in existence by 1745 and is said to have been rebuilt in 1830. (© Derek Kendall)

View from the east of The Black Horse Public House, 40 Leman Street. An inn and public house has stood on this site since the late seventeenth century. The present building appears to date from 1879. (© Derek Kendall)

View from the south of The White Hart Public House and Gunthorpe Street Passage. The White Hart is the only long-standing pub left on the north side of the High Street. On the corner of Gunthorpe Street, an alleyway established by the sixteenth century and formerly known as George Yard, it was certainly here by 1723, when sixteen apparently smuggled bushels of coffee ‘concealed in a Load of Faggots’, were confiscated from the yard of the White Hart Inn. The pub was probably rebuilt in the 1770s and its pilastered frontage dates from a modernisation of the 1830s. (© Derek Kendall)

Front bar of the White Hart Public House. The interior is typical Brewers’ Tudor, from further renovations in the 1920s and 1930s, with dark panelling and suburban-deco leaded-glass panels in the roof light in the rear bar. (© Derek Kendall)

View from the south of Albion Yard, formerly The Albion Brewery, 331–335 Whitechapel Road, which grew from origins in 1807 to become one of London’s major breweries under Mann, Crossman & Paulin, a major local employer and supplier up to closure in 1979. The brewery has been included here partly on account of its links to the longer-lived Blind Beggar public house immediately to its east. (© Derek Kendall)

View of the clock tower of Albion Yard, formerly The Albion Brewery, 331–335 Whitechapel Road. The Albion Brewery was established behind the Blind Beggar in 1807. It was rebuilt and extended in 1863–8 and 1894–1902 for Mann, Crossman & Paulin. In 1958 merger with Watney Combe Reid & Co. created Watney Mann but a restructuring scheme led to closure of the brewery in 1979. The building was converted to flats in 1993–5. (© Derek Kendall)

South elevation of Albion Yard, formerly The Albion Brewery, 331–335 Whitechapel Road. As The Buildings of England has it, this ‘brewhouse’ or fermenting house at the rear of the entrance courtyard is ’embellished in show-off Baroque style’. [1] That work of the late 1890s is likely due to Robert Spence, who was then Mann, Crossman & Paulin’s engineer and architect. The boldly sculpted St George and Dragon panel is the brewery’s trademark, a reference to the patron saint of Albion. (© Derek Kendall)

[1] Bridget Cherry, Charles O’Brien and Nikolaus Pevsner, The Buildings of England, London 5: East, 2005, p. 431.

The Davenant Centre, 179–181 Whitechapel Road: part two

By the Survey of London, on 23 March 2018

A previous blog post (2 March 2018) presented the history of the Davenant School in Whitechapel from the 1680s through to the rebuilding of the Whitechapel Road front building in 1818. The two centuries since are accounted for here. Following closure of the Davenant Centre in 2017, the future of the site seems uncertain.

Foundation School enlargement

The formation of the Charity Commissioners in 1853 led to amalgamation of Whitechapel’s parish charities and the building of a Whitechapel Charities Commercial School on Leman Street. The Education Act and three Endowed Schools Acts of the years around 1870 and growing demand for school places were further backdrops to protracted discussions between the Whitechapel Trustees and the Charity Commissioners. Eventually in 1888 the Whitechapel Charities (embracing St Mary’s School and the Leman Street School) and the Davenant School were merged to form the Whitechapel Foundation, unified in adhering to Church of England religious instruction and amply provided for by historic charitable endowments. What had been Davenant’s Endowed Free School on Whitechapel Road, which had gone through a rocky period, was henceforward the Foundation School, a secondary school for 250 boys which was to be improved with new buildings (and a specified need for a chemical laboratory and workshops). The elementary schools (St Mary’s and Leman Street) were now, confusingly, called the Davenant Schools.

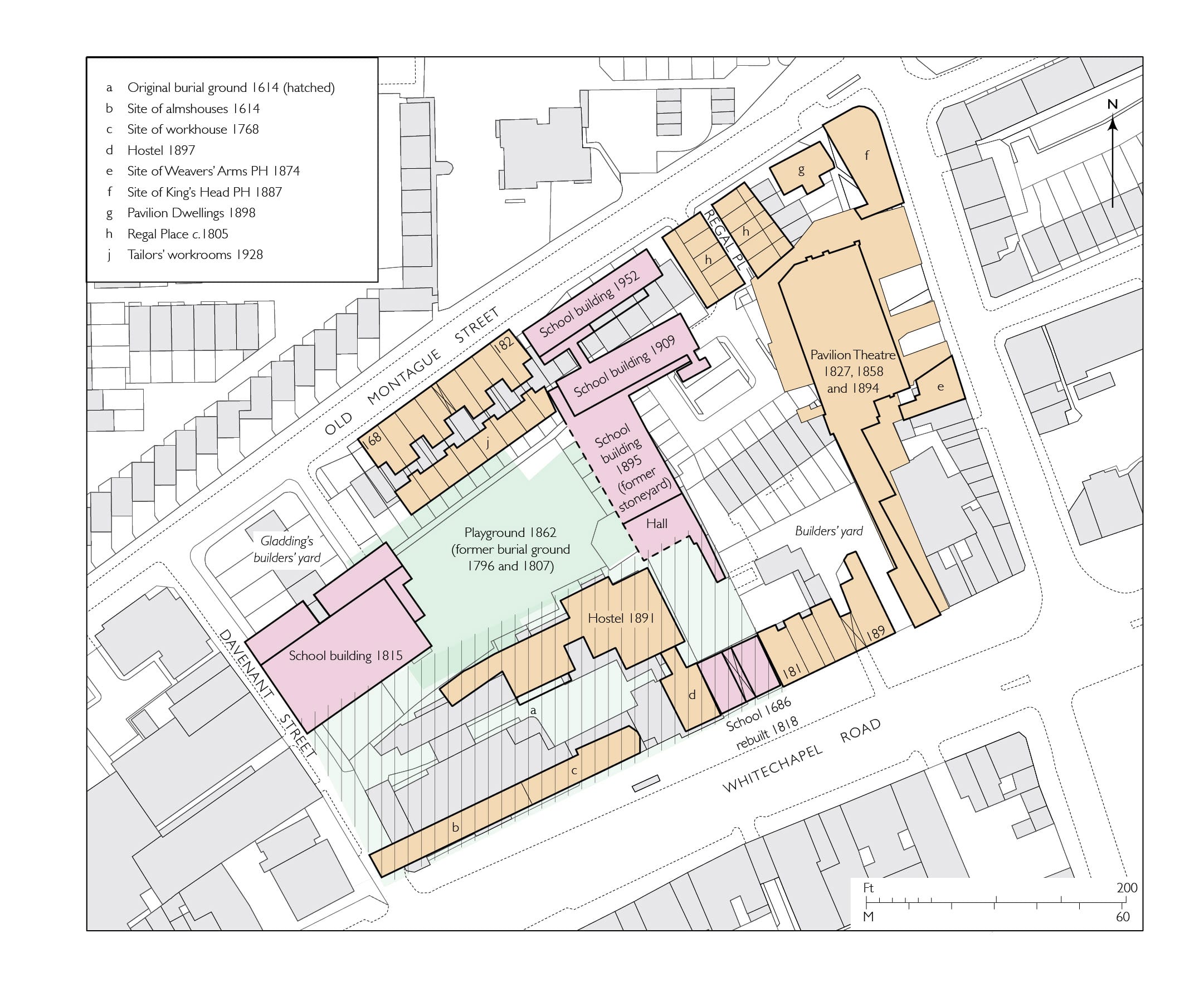

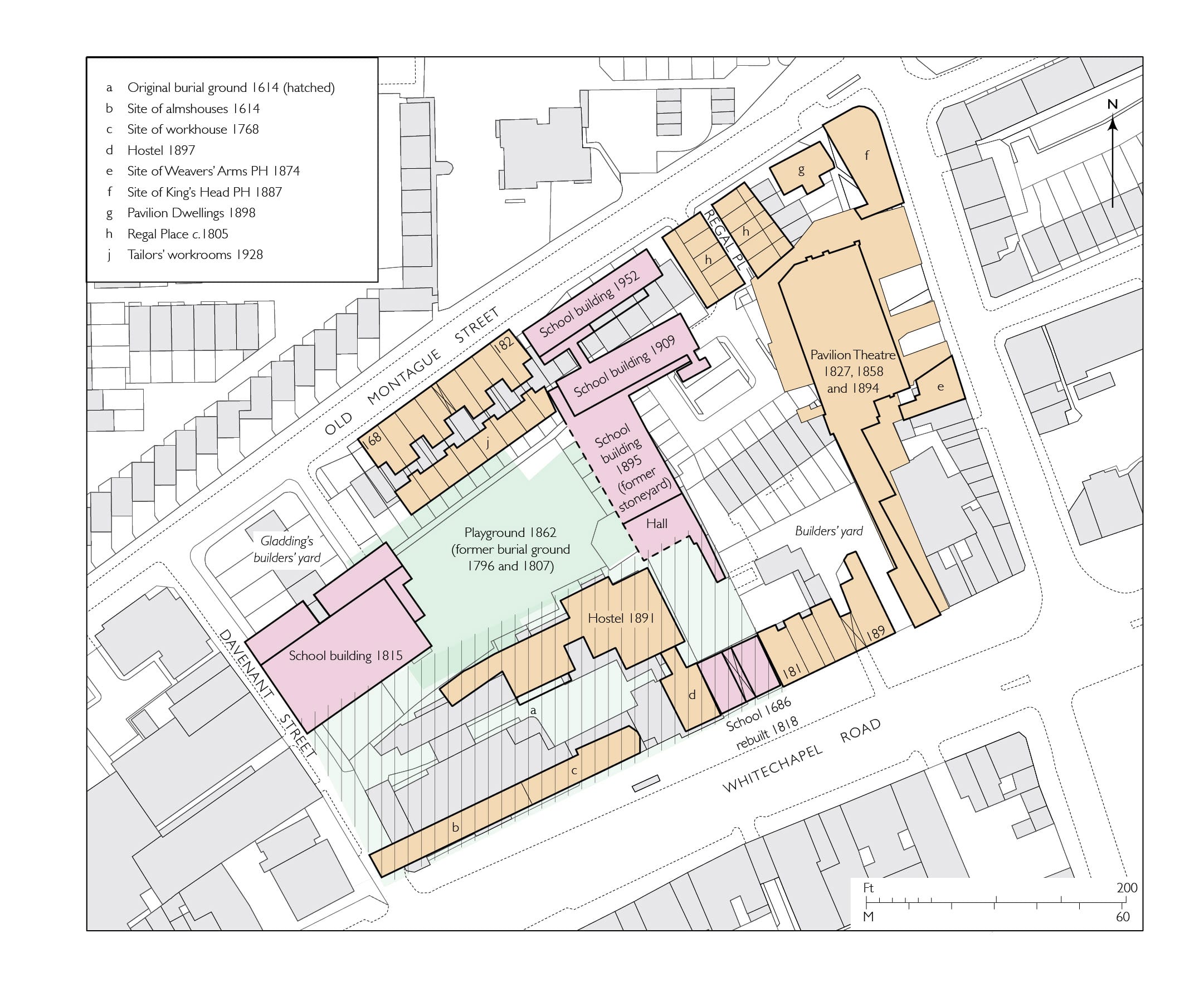

Block plan showing Davenant and related school buildings and principal nearby sites as in 1953, buildings of 2016 in grey. (Drawing by Helen Jones for the Survey of London)

With the new scheme settled, meetings chaired by the Rev. Arthur James Robinson in 1888 quickly approved plans for new buildings by Frank Ponler Telfer, the 24-year old son of one of the new Foundation’s Governors, John Ashbridge Telfer, a pawnbroker of 88 Whitechapel High Street. Another Governor was John Ashbridge, a solicitor based on the south side of Whitechapel Road (where the East London Mosque now stands) and the brother of Arthur Ashbridge, the District Surveyor for Marylebone who on occasions also acted as a surveyor for the Whitechapel Foundation. They were cousins to John Ashbridge Telfer. Their fathers, John Simpson Ashbridge and Somerville Telfer (who married Maria Ashbridge), and grandfather, John Ashbridge, had all been East London pawnbrokers. John Ashbridge and J. A. Telfer were the only Governors besides Robinson to attend a meeting with the Charity Commissioners in July 1888. The young Frank Ponler Telfer, whose mother Mary Ann was the daughter of John Ponler, a Wapping timber merchant, identified himself as a surveyor. He had served an apprenticeship in the City with George Andrew Wilson, architect and surveyor, during which the firm, as Wilson, Son & Aldwinckle, had in 1881 overseen alterations to the Duke’s Head public house immediately east of the school.

Engraved view of the Whitechapel Foundation School, as designed by Frank Ponler Telfer in 1893. (Tower Hamlets Local History Library and Archives)

A first complication to arise in 1890 was to do with the loss of light and air to the west of the school with the building of the Victoria Home (rebuilt in 1995–6 for the Salvation Army as Victoria Court at 177 Whitechapel Road). Arthur Ashbridge dealt with this and Telfer prepared new plans for what was to be called a Commercial School, now working with a new headmaster, Henry Carter. In 1891 the Governors split five to four against a new roadside building and in favour of a new building in the ‘garden’ (the playground and former burial ground), envisaging the road frontage being freed up for shops. Land along Old Montague Street was purchased to supplement what was already owned and four courts of small houses were cleared. On behalf of the Charity Commissioners Ewan Christian approved building in the playground, seemingly unaware that this would contravene the Disused Burial Grounds Act; his suggestions were otherwise largely bypassed. In 1892 nine firms of architects were invited to submit anonymised plans for a building behind the old school on the playground, to be on ‘columns and girders’ for an open ground floor so as not to lose the play space. Five schemes were received. That by Telfer was selected as the best, his father being one of the four inspectors. Other local architects, John C. Hudson and Herbert O. Ellis, placed second and third respectively. Telfer worked up his scheme in 1893 and building work followed in 1894–5 with J. S. Hammond and Son of Romford as contractors. Telfer was asked to ensure that the words ‘The East London Commercial School’ should appear in the floor and that a tablet should commemorate the governors. But the Charity Commissioners disapproved of the name and insisted it be the Whitechapel Foundation School. Fitting out followed in 1896. Already in 1898 most of the sixth-form boys were of Jewish origin, fathers being teachers of Hebrew, a furrier, waterproof manufacturer, butcher, tailor, and poultry and horse slaughterers, coming from as far as Stoke Newington, Camberwell and Upton Park.

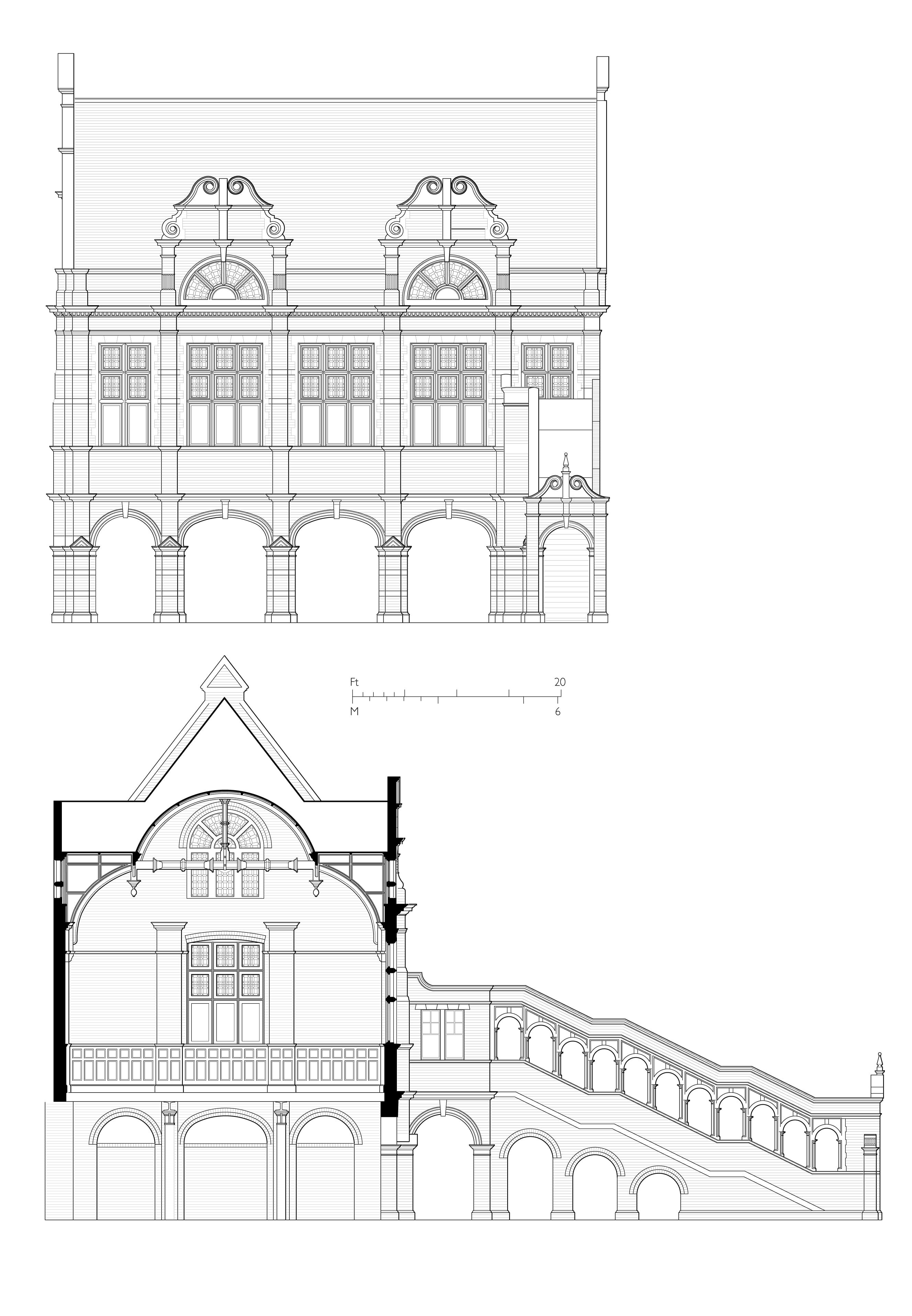

The assembly hall with covered playground and staircase of 1894–5 from the south in 2017. (Photograph by Shahed Saleem for the Survey of London)

Stylistically ‘splendid Neo-Jacobean’, [1] perhaps influenced by E. W. Mountford, Telfer’s two-storey building is of red brick with terracotta dressings, including mullion and transom windows, some with leaded lights, and scrolled gables. The competition brief forced formal ingenuity and resulted in a distinctive parti that is something of an architectural statement, albeit devised from Board School precedents. The ground-floor covered playground was outwardly articulated by arcaded piers. Within, cylindrical cast-iron columns and composite girders support the superstructure. The five-bay east–west assembly hall is grandly gabled – an intended flèche was vetoed by Christian. It has an arch-braced and barrel-vaulted wagon ceiling with turned tie beams and king posts. The south façade was visible from the passage through the old building across a now cleared yard, and the hall was approached by an eye-catching covered staircase with a stepped open arcade. This had been designed to be central, but was moved to the east bay and given a lobby at its head at the building committee’s suggestion, presumably for the sake of a larger yard. A nine-bay north–south range housed six classrooms and staff accommodation.

The covered staircase of 1894–5 from the west in 2017 (photograph by Shahed Saleem for the Survey of London)

Telfer was evidently accomplished, but despite this youthful opportunity his career did not take off. He identified himself in 1901 as an auctioneer, no longer a surveyor. He died in 1907, age 43.

The assembly hall and staircase of 1894–5, south elevation and north-south section looking east. (Drawings by Helen Jones based on record drawings prepared for the Greater London Council in 1984)

From 1900 to 1980

The London County Council and the Board of Education imposed alterations and the addition of a Neo-Georgian north range parallel to Old Montague Street in 1908–9. Designed by Arthur W. Cooksey, this provided four more classrooms, a physics laboratory and an art room. There was no space or money for a gymnasium, but an enclosed fives court was added in 1915–17. This seems to betoken a consciousness of status in what became the Davenant Foundation School in 1928. It was, however, one of the smallest secondary schools in London and the only one unable to provide hot dinners. At the behest of the LCC, negotiations for an amalgamation or a move away from Whitechapel began in 1937, but these were interrupted by war and evacuation. There were wartime alterations to the front range for use as a centre for the Heavy Rescue Service. In the early 1950s voluntary-aid grammar-school status was granted and, despite a falling roll, a new range was added along Old Montague Street for a biology lab, library and two additional classrooms. As one pupil of the 1950s has recalled, ‘there was a large Jewish contingent who had to endure Christian hymns and prayers at morning assemblies. Many of us were already atheists so that side of things just washed over us!’ [2]

Meanwhile, in the face of a decreasing local population, the LCC planned comprehensive redevelopment of the area. The school moved to Loughton, Essex, in 1965, a shift first suggested by the Ministry of Education in 1956. The Greater London Council’s Inner London Education Authority took the Whitechapel site and up to 1971 it was used for Walbrook College’s East London College of Commerce. The Victorian Society, Ancient Monuments Society and GLC Historic Buildings Division resisted a plan for clearance behind the already listed front building, use as a youth centre being suggested. This led to the listing in 1973 of the assembly hall and its staircase. Plans in 1975 to convert the school buildings to be an old persons’ club for the intended ‘Davenant Street’ housing development came to nothing and demolition north of the hall block ensued.

Davenant Centre

A scheme for refurbishment of the two surviving school buildings to be a community centre emerged from the GLC in 1984. In a project spearheaded by George Nicholson, Chair of the Planning Committee in the GLC’s last and defiantly radical days, more than £1m was made available for the formation of the Davenant Centre. This ‘community resources and training centre’ was to extend to include a new building on the empty site at 181–185 Whitechapel Road, all to house eight local groups: the Asian Unemployed Outreach Project, Dishari Shilpi Ghosti (musicians who had left the scene by 1988), the Federation of Bangladeshi Youth Organisations, the Progressive Youth Organisation, Tower Hamlets Advanced Technology Training, the Tower Hamlets Trades Council, the Tower Hamlets Training Forum, and the Jagonari Asian Women’s Resource Centre (which ended up with the adjacent new building – that is another story). With the Historic Buildings Division in close attendance, plans for the adaptation of the listed buildings were drawn up in 1984–5 by Julian Harrap Architects with Peter Stocker as job architect. Harry Neal Ltd carried out the building works in 1985–7, completion coming after the abolition of the GLC and despite an attempt by Westminster City Council to stop the works. The open ground floor under the hall was largely enclosed and the front block gained new stairs and partitions, an upper-storey tiered lecture room being preserved. The Centre’s Chair was Manuhar Ali and Adam Lazarus was its Development Worker. First use was as a youth club and for computer training, welfare advice, trade-union offices and meetings in the assembly hall. There was no reliable source of revenue so the hall had to be advertised for hire and the centre opened as a music venue in 1990.

View to the back of the Davenant Centre’s front building in 2017. (Photograph by Shahed Saleem for the Survey of London)

The Davenant Centre could not sustain itself. Led by Aliur Rahman it was obliged to instigate a further conversion in 2002. Carried out in 2005–6 through ESA Architects (Nic Sampson, job architect), Peter Brett Associates, consulting engineers, and Killby & Gayford, contractors, this introduced much more lettable office use, retaining space for a youth club on the west part of the front block’s ground floor. To maximise floor space a mezzanine floor was inserted, the loft was converted, and a glazed staircase in a ‘cylindrical pod’ was added to the rear. The 1890s hall was also adapted for office use, the interior retained. Despite debts and with support from Tower Hamlets Council the complex continued as the Davenant Centre up to 2017 when, rents having increased, it was obliged to close.

1. Bridget Cherry, Charles O’Brien and Nikolaus Pevsner, The Buildings of England, London 5: East, 2005, p. 400.

2. ‘Davenant Foundation Grammar School’, Survey of London Whitechapel, July 2017.

The Davenant Centre, 179–181 Whitechapel Road: part one

By the Survey of London, on 2 March 2018

An undemonstrative road-side building of 1818 and a showy but concealed rear addition of 1895 are all that is left standing in Whitechapel to represent a significant educational history. This spans more than three centuries and a site that extended from Whitechapel Road to Davenant Street and Old Montague Street. Until 2017 this history was sustained by a youth centre that perpetuated the name Davenant. Its closure in 2017 leaves the future of the two listed buildings uncertain. The history of the Davenant School in Whitechapel will be presented here in a two-part blog post.

First Davenant School

Ralph Davenant was the Rector of Whitechapel from 1668 who oversaw the rebuilding of the parish church of St Mary Matfelon in the 1670s. He was a fellow of Trinity Hall, Cambridge, and a descendant of Bishop John Davenant, a moderate Calvinist who had represented the English church at the synod of Dort in 1618; he was also a cousin to the historian Thomas Fuller. Planning for a school for the poor children of Whitechapel began in earnest in 1680, possibly following up an idea conceived by Davenant’s predecessor and father-in-law John Johnson. Johnson’s daughters, Mary Davenant (Ralph’s wife) and Sarah Gullifer, endowed two of three shares of an estate in Essex (Sandon, near Great Baddow) to be overseen by a newly formed body of trustees to maintain the school. When Davenant died in 1681 his will directed that £200 he was owed go directly to the building of the school, and that his goods be sold after his wife’s death to raise money to see the plan through.

Mary Davenant lived on and the trustees struggled at first to find a site. However, the easterly stretches of Whitechapel Road were not fully built up in the 1680s and the parish held a large plot on the north side to the east of present-day Davenant Street for almshouses and a burial ground. The easternmost part of this land, a frontage of 50ft, was given up for the school in 1686 and building work ensued. Endowments proved insufficient and in 1701 an anonymous benefactor gave £1000 to clothe as well as educate the children at the ‘School House of Whitechappel Town’s End’. In 1705 the Rev. Richard Welton invested this money in Thames-side land at East Tilbury.

The first Davenant School of the 1680s. (From Robert Wilkinson’s Londina Illustrata, 1819)

The school building of the 1680s was a brick range with a seven-bay front, a single full storey with pairs of hipped dormers in a hipped roof flanking a pedimental centrepiece, all set behind a forecourt garden and enclosing brick wall. The main room on the west side was for the teaching of forty boys, that on the east for thirty girls, above were living spaces for the master and mistress. A single central doorway gave on to an open passage through to a garden at the back, the schoolrooms evidently entered from the sides of this passage. An aedicular niche above the main entrance rising up to the open pediment is said to have stood empty until the late eighteenth century, awaiting a figure of Davenant for which funds never stretched. Samuel Hawkins, the school’s Treasurer, then acquired and saw to the painting of a scrapped wooden statue of a figure in clerical dress to make up the deficit. There were further benefactions and by the 1790s the premises, already enlarged westwards after 1767, had been extended at the back.

In early 1806 the Trustees decided to double the number of children and a shed and ‘dust-bin’ behind the school were converted to form an additional schoolroom. Anticipating the increased attendance, one of the Trustees, William Davis (1767–1854), the co-proprietor of a sugarhouse on Rupert Street who was to found the Gower’s Walk ‘school of industry’ in 1807–8, saw to it that the Rev. Andrew Bell was invited to Whitechapel to introduce his monitorial (Madras) system of education which had as yet made limited impact. Bell attended the school daily in September 1806 and with Davis’s fervent support and the employment of a trained assistant (Louis Warren, age 13), and then of a schoolmaster (a Mr Gover), both from Bell’s base in Swanage, they successfully established a showpiece in Whitechapel for wider evangelisation of the benefits of Bell’s monitorial system. This gained influential Anglican support and led in late 1811 to the foundation of the National Society for the Education of the Poor in the Principles of the Established Church in England and Wales. The episode has caused the Davenant School to be hailed as the cradle of England’s ‘National’ schools.

Block plan showing Davenant and related school buildings and principal nearby sites as in 1953 (buildings of 2016 in grey), drawing by Helen Jones for the Survey of London. Please click on the picture for a larger view.

St Mary Street School

There followed in September 1812 the formation of the Whitechapel Society for the Education of the Poor, as a branch of the National Society. Daniel Mathias, Whitechapel’s Rector since 1807, headed this initiative towards educating more of Whitechapel’s poor children. A survey of the parish had uncovered 5,161 children under the age of seven and 3,204 above that age. Of the latter, 991 attended the thirty-two schools already in the parish, leaving 2,213 uneducated. Few parents attended church, providing an additional motive for the evangelical Society. A scheme coalesced for the establishment of a new school with a hall large enough for 1,000 to be taught on Bell’s (National Society) principles; it would also be used for religious service on Sundays. The first thought was to procure an adaptable building, but by early 1813 there were plans to build on land to the north of the 1680s school and a lease was agreed. In the event the Society decided to use this land to extend the parish’s burial ground eastwards and to build the school on the west part of the burial ground to face the recently formed St Mary (now Davenant) Street. The Vestry gave up the land and the Bishop of London approved the project in the summer of 1813. However, funds were wanting; despite a grant of £300 from the National Society, the building fund was more than £1,000 short of its target of £2,500. The Duke of Cambridge laid a foundation stone on 12 October 1813 in an opulent ceremony said to have been attended by thousands; that brought in £677 11 6 in donations. Completed in 1815, the building was among the earliest purpose-built National schools. It was also, as Nikolaus Pevsner had it in an unconscious recognition of the intended secondary use, ‘like a chapel’. [1]

Davenant (formerly St Mary) Street in 1973, showing the National School of 1813-15. (Photograph by Dan Cruickshank at Tower Hamlets Local History Library and Archives)

Its architect remains unknown, though for circumstantial reasons Samuel Page is a candidate, as will be explained. It was a single-storey stock-brick barn of about 80ft by 120ft. Its round-headed window openings, some very tall, had cast-iron Gothic tracery. There were porches at both ends and a western clock turret. The main square room to the west was for the teaching of 600 boys, with a half-sized room beyond for 400 girls, all convertible into a single space. Two rows of square timber posts helped support a vast queen-post truss timber roof. There was a hot-air heating system, devised and paid for by Davis with John Craven, another Goodman’s Fields sugar-baker. Tom Flood Cutbush (the son-in-law of Luke Flood, see below) procured an organ, which he played himself, also arranging performances of oratorios in the 1820s.

In 1844–5 the Rev. William Weldon Champneys oversaw reconfiguration of the east end, the girls’ room reduced, raised and given a railed balcony to create space below for an infants’ school, with living rooms for the master and mistress. Other subdivision for classrooms in the western corners followed in 1868–9 with G. H. Simmonds as architect.

Ordnance Survey map, 1873, showing the Davenant and St Mary Street schools.

The west porch was lost when St Mary Street was widened in 1881–2. George Lansbury, an alumnus around 1870, recalled ‘what a school-building! No classrooms, one huge room with classes in each corner and one in the middle.’ [2] The east part of the burial ground, disused from 1853, was taken for a playground from 1862. This was shared with the Davenant School as well as the Whitechapel Union, for which a disinfecting house was inserted in the ground’s north-east corner at the south end of Eagle Place in 1871. This workhouse shed gained notoriety as the mortuary to which some of the victims of ‘Jack the Ripper’ were taken in 1888. It was thereafter replaced. The National School was also known as the Whitechapel Society’s School, St Mary’s School or St Mary Street School. In 1874, 360 children were presented for examinations, a decade later 443. It had less cachet than the Davenant School, which, to Lansbury, was for ‘“charity sprats” – girls and boys dressed in ridiculous uniforms’. [3] After administrative changes there were adaptations in 1889–90, including the addition of a caretaker’s house to the north. The school continued under London County Council maintenance as Davenant Elementary Schools, its roll gradually declining from 784 in 1900 to 300 in 1938. It closed in 1939. After post-war use as a second-hand clothing warehouse and despite calls for its preservation, the building was demolished in 1975.

St Mary Street School in course of demolition in 1975. (Photograph by Michael Apted, courtesy of Historic England Archive)

Davenant School rebuilt

Rebuilding of the original schools of the 1680s by the Charity School Trustees followed hard on the heels of the opening of the National School. Larger premises were wanted to accommodate 100 boys and 100 girls, again for the application of Bell’s system. The funding of this project had been given a start by Samuel Hawkins, who had donated £600 in 1808 for building a new school, and a coachbuilder called Lewis (possibly Thomas Lewis, a coach-master of 45 Leman Street), who gave £500 in 1817. Mathias was still the Rector and the Treasurer for the trustees was Luke Flood (1738–1818), a painter, corn chandler and corrupt magistrate and commissioner of sewers who had premises on Whitechapel Road (on the site of No. 57). Flood left £1,000 to the school when he died in February 1818; this was the most munificent of the period’s gifts. Flood’s son-in-law was the architect Samuel Page who had been acting as a surveyor for the parish since at least 1807. Around 1813 Page was also involved in securing an improved endowment for the school. It seems likely that he was charged with designing the school building; it is a characteristically sub-Soanian work. He was probably working with Thomas Barnes, the local bricklayer and house-builder, another trustee and commissioner of sewers who contributed £100 to the fund in 1818. Major Rohde, a Leman Street sugar refiner, was also a trustee. Another was William Davis, who succeeded Flood as Treasurer. The foundation stone was laid in June 1818 by the Duke of York; completion evidently followed quickly.

The Davenant School’s front building of 1818, photographed as the Davenant Centre in 2017, by Derek Kendall for the Survey of London.

The two-storey and basement five-bay yellow stock-brick building, roughly square on plan, was laid out to align with the workhouse. It originally had steps up to a raised ground floor at its central entrance arch, with a deeper railed area in front of the basement, and a dedicatory stone plaque in a blind arch above the entrance. There was a central staircase and a single classroom to each side on each of the main storeys. In the 1860s, after outbuildings to the west were given up, two blocks were built in the yard for boys, the front range being given over to girls. The plaque had been taken down before major changes in the mid 1890s that were part of a thorough reformation (of which more in the second post). The steps and the staircase were removed with the railings pushed back for a ground floor at pavement level for improved access to new buildings behind – a return to the open passage arrangement of the 1680s. The tympanum of the entrance arch gained a foliate terracotta panel (lost around 1980) and the legend above was changed from DAVENANT-SCHOOL to THE FOUNDATION SCHOOL in 1896, retaining WHITECHAPEL SCHOOL on the central blocking-course parapet above. The schoolrooms were converted in the 1890s to be a chemical laboratory and two workshops, a lecture room, library and dining room, with caretaker’s quarters.

To be continued.

Do you have any memories of the Davenant School? The Survey of London has launched a collaborative website titled ‘Histories of Whitechapel’ and welcomes contributions. Please visit: https://surveyoflondon.org/map/feature/452/detail/#story.

References

1 – Nikolaus Pevsner, The Buildings of England: London except the Cities of London and Westminster, 1952, p. 426.

2 – As quoted in Roland Reynolds, The History of the Davenant Foundation Grammar School, 1966, p.51.

3 – Ibid.

Francis Sheppard (1921–2018)

By the Survey of London, on 9 February 2018

The Survey of London is sad to announce the death of Francis Sheppard at the advanced age of 96. Francis was the first General Editor of the Survey, between 1954 and 1983. During those 29 years he published sixteen volumes in its main or ‘parish’ series, an amazing rate of better than one volume every two years. Incomparably the most successful and productive editor the Survey has had, he stands second only to its founder, C. R. Ashbee, in stature and attainment.

Francis Sheppard soon after his appointment to General Editor of the Survey of London in 1954.

Francis came to the Survey of London at one of the many turning points in its history. For the first half of the twentieth century, the writing, research and publication of the series had been precariously balanced between an amateur committee of scholars and the London County Council, which over the years had taken on increasingly more of the costs and tasks involved. After the Second World War the committee could no longer continue, so the LCC was faced with bearing the whole responsibility. At first the editing work was undertaken by the remarkable Ida Darlington, who had started working on the Survey as an assistant in the 1920s but was promoted after the war to be the Council’s chief librarian. She produced two excellent volumes on Southwark (Volumes 23 and 25 in the series). But she could hardly carry on doing both jobs. So the LCC advertised for a full-time General Editor, with the brief of producing the Survey more regularly (once a year was the aspiration). The editor was to work closely with the LCC’s developing Historic Buildings Division, which would go on supplying the illustrations and the old-fashioned ‘architectural descriptions’ then still prevalent.

Francis Sheppard at work.

It was Francis’s achievement to turn this delicate assignment into a triumph, by dint of brilliant scholarship, tact, utter trustworthiness, amiability of manner and sheer hard work. He soon won the confidence of the LCC’s small Historic Buildings advisory committee, which at various times embraced such luminaries as John Summerson, John Betjeman and Osbert Lancaster. When the first of the Sheppard series, Volume 26 on South Lambeth, appeared in 1956, it was hailed by Betjeman (not yet on the HB committee) as ‘this great book’. Next he concentrated at the Historic Buildings Division’s request on the West End of London, where many Georgian streets faced possible redevelopment. There had previously been little in-depth scholarship on areas rich in architecture like St James’s, Soho and Mayfair. Between 1960 and 1980 Francis and his colleagues transformed the position, and in the process helped tip the balance towards the preservation of whole swathes of urban fabric. The most famous case was Covent Garden, where the Survey’s investigations, published in Volume 36 of the series, led to the listing of many previously overlooked buildings and helped lead to the drastic modification of the Greater London Council’s redevelopment plans for the area. The Survey and the Historic Buildings Division had been transferred over from the LCC to the GLC in 1965, and the planning controversies over Covent Garden were among many struggles within the Council. But Francis always wisely kept his head down, proving the Survey’s value by the reliability, quality and presentation of his team’s findings.

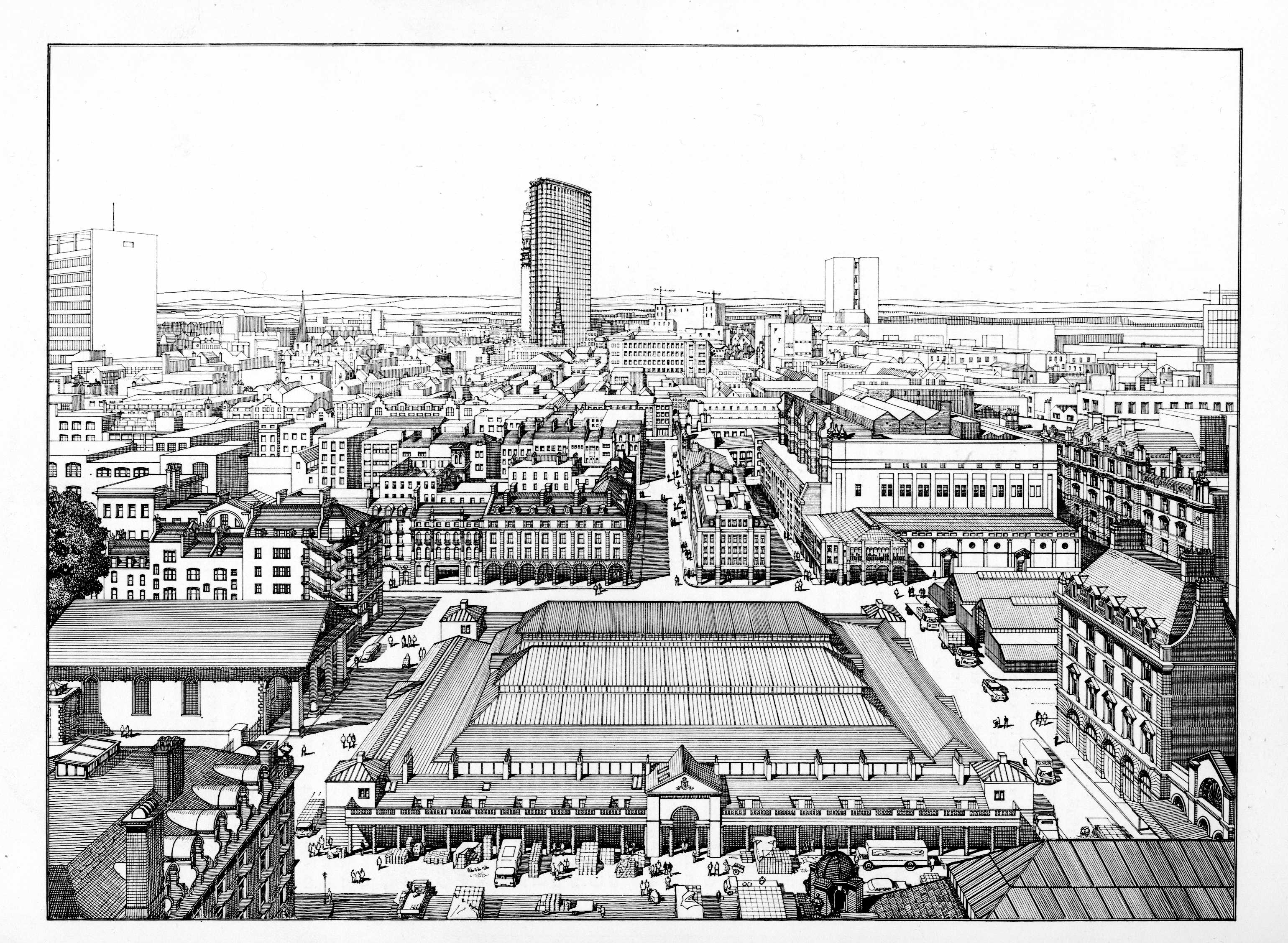

Bird’s-eye view of Covent Garden Market area. Drawn by F. A. Evans and T. P. O’Connor. (Survey of London, Volume 36, Covent Garden, 1970)

Never one to put himself forward, Francis always attributed much of the Survey’s growing reputation in those years to his colleagues. They included Marie Draper, who began working on the Survey in Ida Darlington’s day and did much of the research for the early history of Covent Garden, before becoming archivist to the Bedford Estate; Peter Bezodis, who took on the ground-breaking Volume 27 on Spitalfields almost single-handed, became Francis’s official deputy, and carried on with the Survey into the 1990s; and, latterly, Victor Belcher, John Greenacombe and Andrew Saint. But throughout his editorship Francis was the series’ mainstay and most productive writer. The Survey’s texts have always been firmly anonymous, but it is not hard to spot his direct and driving style of narrative writing. He loved nothing more than to piece together the complex story of some famous building. Examples of Sheppard setpieces are the accounts of Burlington House in Volume 32, the Pantheon in Volume 32 and the Royal Opera House in Volume 35.

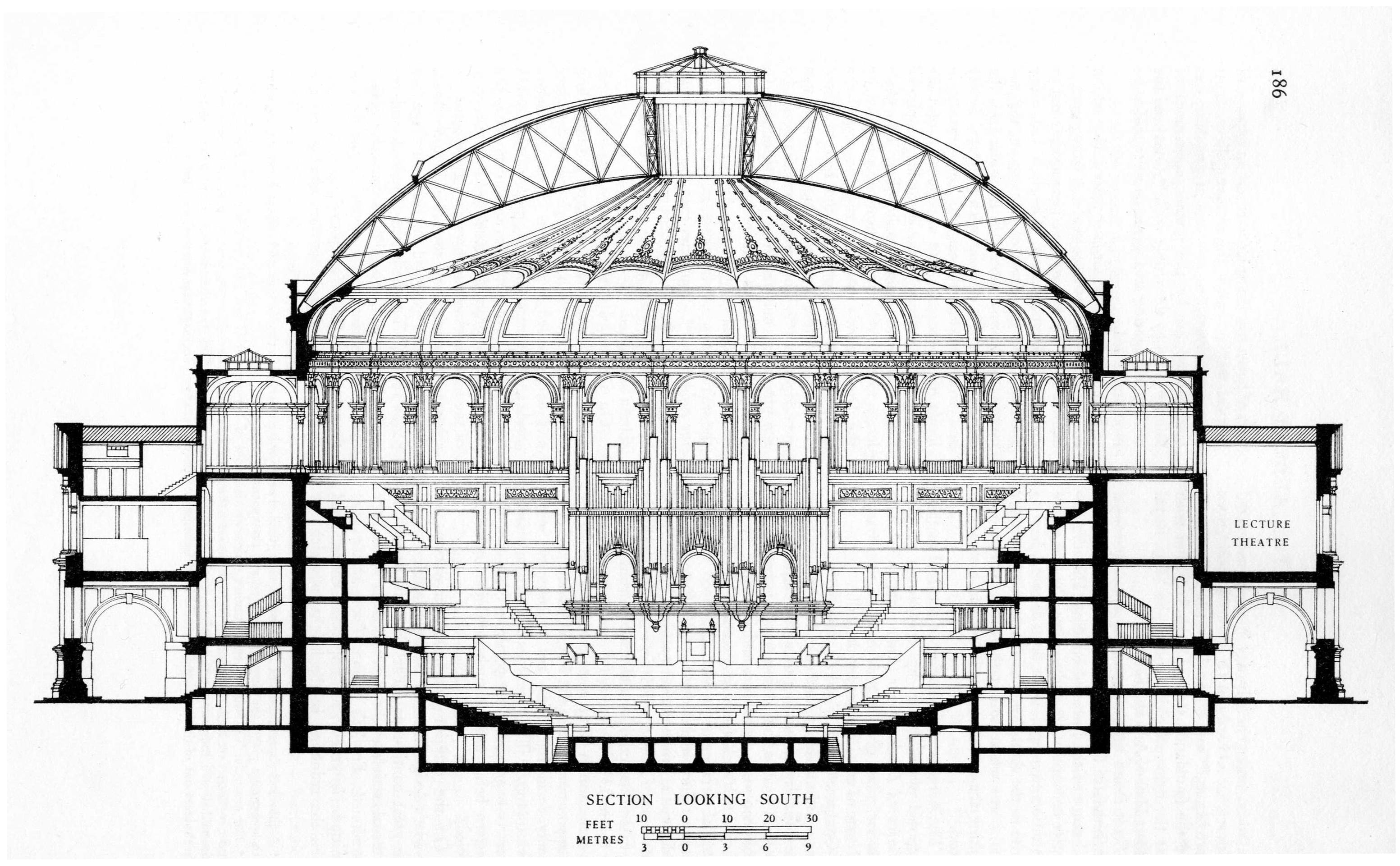

Royal Albert Hall, section looking south in 1932. Redrawn by F. A. Evans. (Survey of London, Volume 38, South Kensington Museums Area, 1975)

The Survey has always evolved. In the 1970s Francis turned its attention to Kensington, where he had been brought up. In Kensington, notably North Kensington, the first area to be tackled, the totality of the Victorian townscape was of greater moment than individual works of architecture. It became the Survey’s task to tease out how the original building development had come into being. Always eager to learn, Francis at this stage was greatly influenced by the new holistic urban history championed by his friend Jim (H. J.) Dyos, Michael Thompson, Michael Robbins and others. Volume 37, Northern Kensington, published in 1973, represented a fresh breakthrough. It has been many people’s favourite volume of the Survey ever since, with its beautiful drawings arranged in a freshly graceful format by the architectural editor of the time, James Stevens Curl, and largely drawn by the gifted John Sambrook. As to the text of Volume 37, packed with revelations about the doings and dealings of hitherto obscure local builders, Francis always attributed many of its innovations to Victor Belcher.

Nos. 2–8 (consec.) Lansdowne Walk, plans, elevations and details. Drawn by F. A. Evans. (Survey of London, Volume 37, Northern Kensington, 1973)

By the time Francis retired in 1983, three of the four Kensington volumes had been published. The unique formula on which the Survey prides itself today was by then in place: an all-but complete coverage of the built fabric of each area covered, with architecture to the fore, but underpinned by a full treatment of the social and economic character of the locality. Francis found the Survey of London a partial history of the best buildings in each parish. He left it a thriving and integrated record of London’s urban history, without a rival in any other major city.

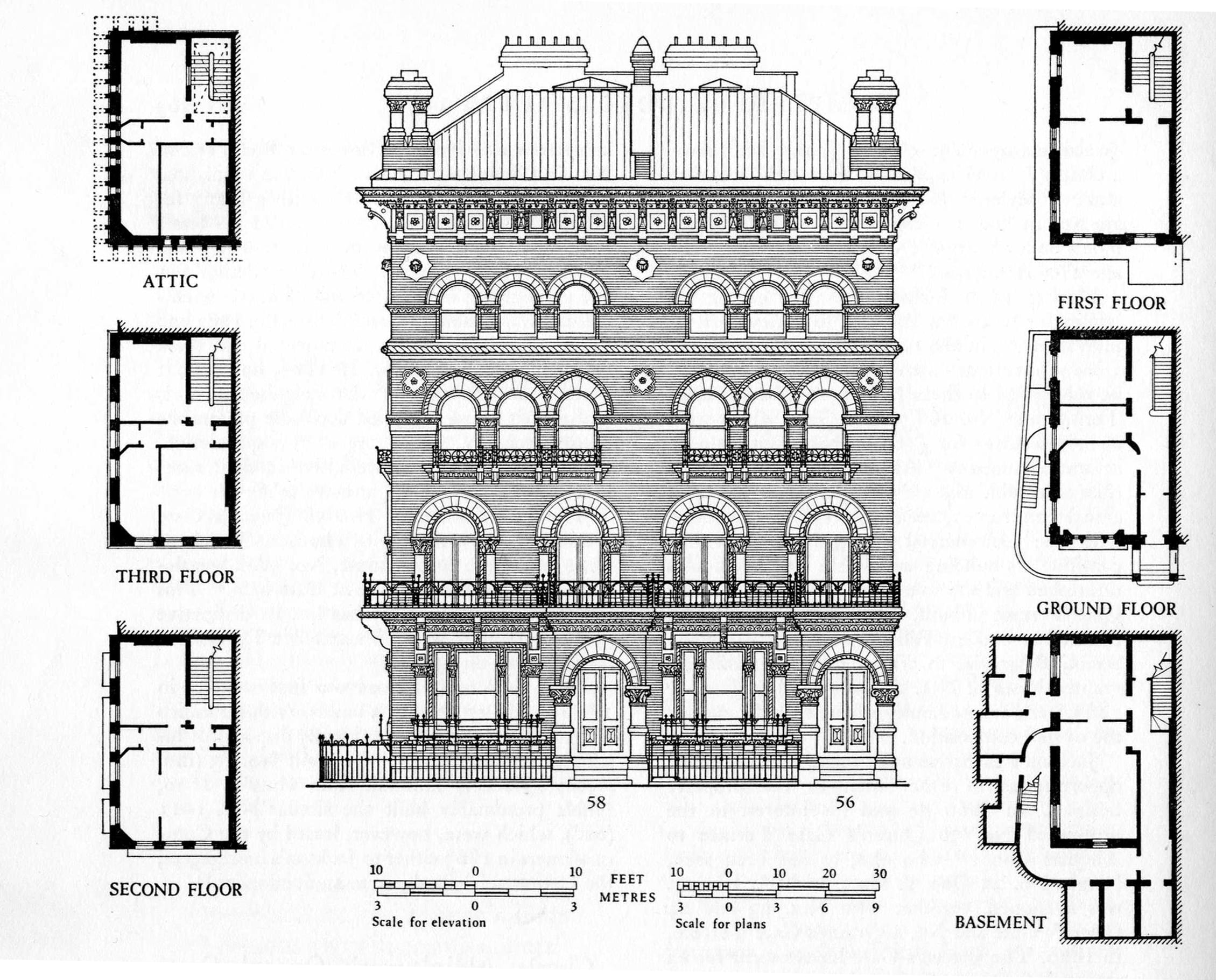

Nos. 56 and 58 Queen’s Gate Terrace, plans, elevations and details. Drawn by John Sambrook. (Survey of London, Volume 38, South Kensington Museums Area, 1975)

Despite his formidable work-rate on the Survey, Francis found time to write widely in his own name: learned articles, reviews (often for the now defunct Books and Bookmen) and books. His classic London, The Infernal Wen 1808–1870 came out in 1971, and a history of Brakspear’s, the Henley-on-Thames brewery across the street from where he lived, in 1979. Believing that his family deserved more space and better air than ‘the wen’ could afford, he had moved to Henley in the early 1950s, putting up with the punishing commute to London almost daily.

Nos. 93–98 Park Lane, details of decorative ironwork. Drawn by Frank Evans. (Survey of London, Volume 39, The Grosvenor Estate in Mayfair, Part I, 1977)

Astonishingly he was also deeply involved with Henley’s civic life, where he served as councillor, alderman and mayor in 1970–1. That all began with a conservation struggle to save the venerable Catherine Wheel Inn in Hart Street, Henley. After his triumph over the developers, Francis set up the Henley Society. In his retirement years he wrote a history of the Museum of London, where he had been employed before working on the Survey, and a general history of London. He had a wide circle of friends in and around Henley, closest among them perhaps the historian Christopher Hibbert.

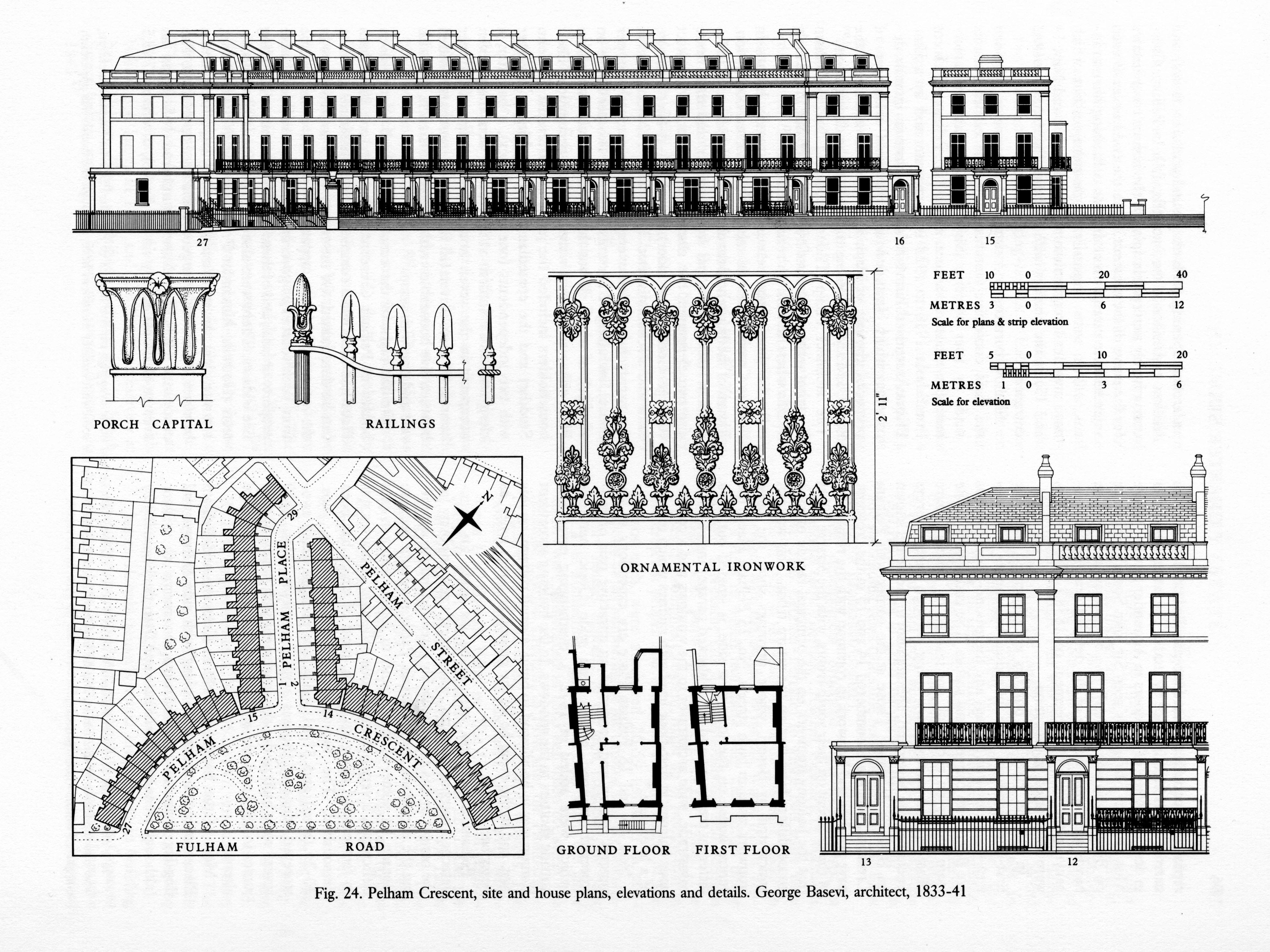

Pelham Crescent, site and house plans, elevations and details. Drawn by John Sambrook. (Survey of London, Volume 41, Brompton, 1983)

None of this was familiar to his colleagues, because Francis was a private and reticent person, though he could be excellent company, a warm friend and very funny when he chose. He is greatly honoured by his surviving colleagues and present-day successors.

Survey of London ‘Main Series’ volumes published under Sheppard’s editorship.

The ‘bijou’ or ‘dwarf’ houses of the Howard de Walden grid. Part 2: the inter-war period

By the Survey of London, on 19 January 2018

A previous blog post (24 November 2017) considered the smaller Victorian and Edwardian mews-corner houses that are such a distinctive feature of the east-west streets of the Howard de Walden Estate in Marylebone. Today we look at three exceptionally fine later examples of the genre, all designed for the Marylebone builders and developers Bovis Ltd by notable architects of the inter-war period – Sir Giles Gilbert Scott, G. Grey Wornum, and Burnet, Tait & Lorne.

22 Weymouth Street – a house by Giles Gilbert Scott

22 Weymouth Street (photographed by Chris Redgrave for the Survey of London, © Historic England)

22 Weymouth Street is one of Marylebone’s jewels – a rare domestic work by Sir Giles Gilbert Scott, designed in the early 1930s when he was at the height of his powers and working also on Cambridge University Library and Battersea Power Station.

The house was a speculation for Vincent Gluckstein, chairman of Bovis Ltd, who had been chasing the site since 1928, having recently rebuilt No. 26, a few doors along. Initially, the Howard de Walden Estate suggested two small residences as possible replacements for the double-fronted house that previously stood here. But Gluckstein eventually had his way and devoted the whole plot to just one, larger house, for which Scott was providing plans by 1933, assisted by his younger brother Adrian.

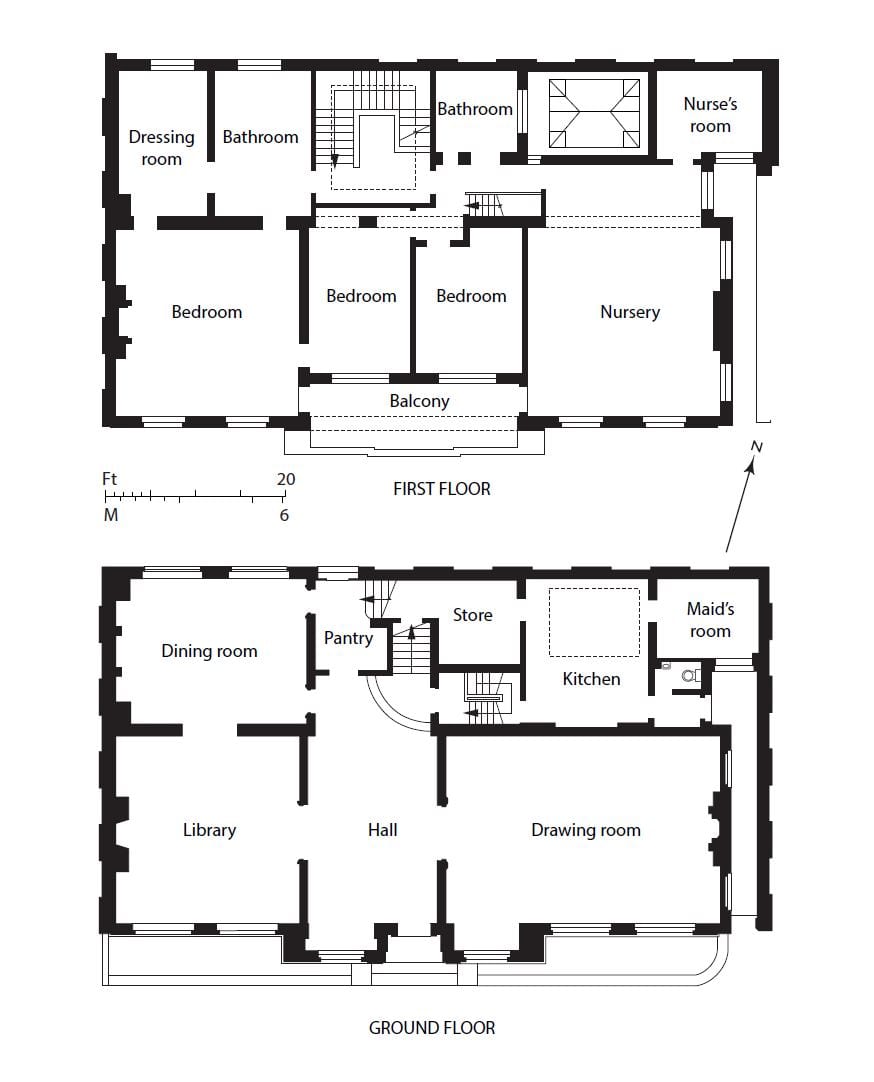

Even so this was still a compact dwelling and as such was carefully planned by the Scotts. There was only a partial basement, occupied by a boiler room. The kitchen, pantry and maid’s room were placed at the rear of the ground floor, which otherwise was given over to a suite of reception rooms: a front library and drawing room either side of a central hall, and a rear dining room. Upstairs were bed and other family rooms, and servants’ accommodation was provided in an attic, lit by rear windows.

In form the house is an updated version of the earlier mews corner houses hereabouts, being of two storeys only, though with a tiled mansard roof for the attic. Scott relied on high-quality brickwork and his immaculate sense of proportion for effect. The elevation has a classic, symmetrical simplicity, dominated by the broad, Georgian-style fenestration, with movement provided by the subtle interplay of rectangular forms – the ground-floor windows either side of the door break forward to make an entrance porch (apparently a late alteration to the design), above which the first-floor central windows are recessed as a sun balcony. The overall effect is very similar to the two-storey brick house that Scott had built for himself a decade earlier in Clarendon Place, Bayswater (known as Chester House). Inside No. 22 the feeling of modernity gave way to a more conventional ambience, with much timber panelling, particularly in the library, and the use throughout of antique carved marble or timber fireplaces.

Scott’s exceptional ability to leaven his unpretentious brand of modern architecture with a strong dose of traditionalism eased relations with the Howard de Walden Estate, as did the fact that he and his brother shared an alma mater (Beaumont College) with their fellow Roman Catholic Colonel Blount, the estate surveyor. Thus he was spared the worst of the wearying interference from Blount that plagued his contemporaries G. Grey Wornum and Francis Lorne over the mews corner houses that they were also designing for Bovis. In the end, however, he lost his patience when Blount, a stickler for uniformity, persisted in criticizing the variegation of the bricks – the identical four-inch type that Scott had specified for Cambridge University Library, then also under construction, where they had been roundly praised. ‘It is quite impossible to obtain any coherent effect unless such questions are under one control’, Scott told Blount candidly.

The house must have been close to completion by the end of 1934 when it featured in the architectural press but no acceptable buyer came forward when offered for sale in 1936. Vincent Gluckstein seems to have been using the property himself at that time. Its next occupant in 1938 was (Sir) Eric William Riches, a surgeon at the Middlesex Hospital. As Riches intended also to practice privately, the drawing room was partitioned for him to create a suite of consulting and examination rooms and secretary’s office. Riches was to remain at No. 22 until 1976, since when the partitions have been removed and the drawing room reinstated. Later residents included the multimillionaire Indian businessman G. K. Chanrai and his family in the 1980s and 90s.

Proposals for radical change to the house in 2009, including the addition of another storey, led to its being listed at the request of the Twentieth Century Society.

39 and 40 Devonshire Street – two houses by Burnet, Tait & Lorne

39 and 40 Devonshire Street form a surprising pair of dwellings. The latter has an idiosyncratic neo-Georgian street front, with prominent window shutters and a steep pyramidal roof punctured at the eaves by dormer windows; whereas its partner, tucked away in the mews, is starkly modern in appearance. They were designed as a pair in the early 1930s for Vincent Gluckstein by Sir John Burnet, Tait & Lorne, with some input from the Howard de Walden estate surveyor, Colonel Blount.

40 Devonshire Street, at the corner with Devonshire Close (photographed by Chris Redgrave for the Survey of London, © Historic England)

39 Devonshire Street (photographed by Chris Redgrave for the Survey of London, © Historic England)

By 1930 Gluckstein had decided to buy the old premises on this corner site, which included a mews pub, the Cape of Good Hope, intending to demolish all for new residences. Burnet, Tait & Lorne began planning in the summer of 1931 but financial concerns about the effects of the Depression on property obliged Gluckstein to proceed initially with only the mews house at No. 39. The dapper and worldly Francis Lorne, a recent addition to the practice after a lengthy residence in Canada and the USA, was the partner in charge. He, his American brother-in-law Ludovic Gordon Farquhar (who had worked for Raymond Hood) and their international team of assistants designed a relatively plain two-storey brick box with steel-framed windows. Lorne also dealt effectively with Blount’s disquiet and requests for a more traditional type of house (‘we have a reputation to maintain’, Lorne told him), and was able to carry the scheme through without too much alteration – though the incorporation of window shutters is a familiar Blount touch. Even so, perhaps the style was too raw for Marylebone society as the building never saw residential use, being acquired in 1933 by G. Grey Wornum and converted to his architectural offices. Wornum was succeeded in 1950 by Sydney Clough, Son & Partners. Poor modern refenestration has diluted the building’s vigour.

39 Devonshire Street in 1933 (© Historic England Archive)

39 Devonshire Street, interior in 1933, when in the occupation of G. Grey Wornum (© Historic England Archive)

Lorne and Farquhar must have known that such an uncompromising elevation, difficult enough to achieve in a mews, would be unacceptable on a Marylebone street front. At No. 40 the brand of Georgian Revival architecture they contrived is reminiscent of Lutyens’s domestic Queen Anne style of the 1910s. The obtrusive shutters, which detract from the design’s clarity, were not present in their original drawings. The first resident in 1935 was Louis Donn, of a Whitechapel family of tobacco merchants.

39 Weymouth Street – a house by G. Grey Wornum

Beyond the Harley Street Clinic, at the corner of Wimpole Mews, stands 39 Weymouth Street, one of the 1930s rebuildings in the area by Bovis Ltd, in this instance the work of G. Grey Wornum, architect of the new RIBA headquarters on Portland Place. That commission won him renown for spatial dexterity and commitment to high-quality fittings, qualities apparent in this interesting house.

39 Weymouth Street (photographed by Chris Redgrave for the Survey of London © Historic England)

Wornum’s involvement is not readily discernible from the rather staid Georgian-style frontage. His original plans of 1934 for Vincent Gluckstein of Bovis were more radical, for a flat-roofed modernistic house, but Colonel Blount, the Howard de Walden surveyor, wanted something more ‘pleasing’ and in harmony with the traditional character of the estate. Forced to concede to Blount’s insistence on a pitched roof, he managed largely to conceal it behind a high parapet, but ignored persistent requests for distracting window shutters to be added to the elevation. The only contemporary touch is the Deco curve of the rear wall in the adjoining mews.

39 Weymouth Street, rear view from mews (photographed by Chris Redgrave for the Survey of London © Historic England)

But Wornum’s hand was to the fore inside. Although the house is not listed and has been modernized on several occasions, its interior retains much of the character and some of the features of his original design. The main living space is an exhilarating double-height front room, dominated by an oversized window and giant chimneypiece of pink travertine marble – still with its Wornum-designed firedogs. The room’s original proportions have been restored by the removal of a pair of full-height bookcases either side of the chimneypiece, commissioned from Dennis Lennon in the 1960s. An opening leads to a small dining recess (with its original dumb waiter, concealed in a macassar ebony sideboard), and a curved staircase leads up to a mezzanine in the form of a small wood-panelled study overlooking the main living room. The original finish here was bleached Australian walnut; there were concealed striplights to the fitted bookshelves and a pale leather covering to the balcony handrail (now gone). Two bedrooms on the first floor had built-in wardrobes and the living space was maximized by including a roof garden and also a three-bedroomed staff apartment in the basement alongside a large, rubber-floored kitchen.

39 Weymouth Street, hall and staircase (photographed by Chris Redgrave for the Survey of London © Historic England)

The first resident from 1936 until the 1950s was Thomas Lyddon Gardner, chairman and managing director of the Yardley Perfumery and Cosmetics Company, and it is possible that the house was designed specifically for him through Bovis. Photographs of it newly finished were reproduced in the Architect & Building News in 1936 with furniture by Émile-Jacques Ruhlmann much in evidence. Lyddon Gardner was a great admirer of Ruhlmann, commissioning him to design furniture in the 1920s and 30s for Yardley’s showroom in Bond Street and acquiring pieces to decorate his own apartment; Ruhlmann also designed for the Yardley showroom in Paris. Lyddon Gardner was followed at No. 39 by (Sir) David Webster, Director of the Royal Opera, who lived here with his partner, the designer and fashion businessman James Cleveland Belle, until his death in 1971.

The Survey of London, December 2017

By the Survey of London, on 29 December 2017

Recently we have been looking through our archive on the history of the Survey of London, which traces its beginnings to the 1890s. These large cloth-bound boxes brimming with letters, newspaper cuttings, photographs and pamphlets include detailed reports on the progress of the Survey.

A pamphlet recording the progress of the London Survey Committee, as the Survey was formerly known, at Midsummer 1929.

As it is customary during the festive season to reflect on recent achievements, current research, and plans for the future, we think it might be timely to share an update on the current progress of the Survey. 2017 has been an important year for the Survey of London, marked by the publication of Volumes 51 and 52 on South-East Marylebone by Yale University Press, supported by the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art. We are delighted that these volumes, which document a rich and varied part of the capital, have been received with glowing reviews:

- “Superbly researched, well written and comprehensively illustrated…” – John Martin Robinson, Country Life, October 2017.

- “These two [volumes] cover a chunk of the historic West End in unrivalled detail following years of rigorous research…” – Robert Bevan, Evening Standard, December 2017.

The draft chapters for these volumes have been made freely available online via our website.

Covers of Volumes 51 and 52 of the Survey of London on South-East Marylebone, published in Autumn 2017.

The Survey is following up its two volumes on South-East Marylebone with a study of South-West Marylebone, covering the area west of the boundary of the previous volumes as far as Edgware Road. A comprehensive study of Oxford Street is also underway to produce a volume covering both sides of the street from Tottenham Court Road to Marble Arch. As the longest continuous shopping street in Europe since the eighteenth century, Oxford Street is a unique phenomenon. Though it has witnessed almost continuous change, it has never lost its popularity. The traffic, the crowds and the modes of transport will be an equal part of the Survey’s study along with the buildings and shops of Oxford Street. Publication date is estimated as 2019.

View of Oxford Circus taken from the roof of Spirella House, 266–270 Regent Street, looking north-west. (© Survey of London, Lucy Millson-Watkins)

Research is continuing in Whitechapel, an area with a multifaceted history that is currently in the throes of intense change. In Autumn 2016 the Survey launched a public collaborative website, ‘Histories of Whitechapel’, with the involvement of the Bartlett Centre of Advanced Spatial Analysis at UCL and supported by a grant from the Arts and Humanities Research Council. This ongoing project is an experiment in the public co-production of research, which during the last year has encompassed oral-history interviews, walking tours, exhibitions, and film viewings, all in addition to the combination of rigorous research, field investigation and architectural drawings that is the mainstay of the Survey of London series.

View of Whitechapel Road in 2015, looking east towards the City. (© Survey of London, Derek Kendall)

As many of our readers will know, the Survey has been based at the UCL Bartlett School of Architecture since 2013. Research has recently begun towards an in-depth study of University College London for the Survey’s monograph series, which is devoted to buildings and sites of particular note. The forthcoming monograph will focus on UCL’s Bloomsbury campus, the historic core of the university’s estate. Publication date is intended as 2026, to coincide with celebrations for the bicentenary of the university’s foundation.

View of UCL’s main quadrangle from Gower Street, looking east towards the dignified Corinthian portico of the Wilkins Building. (© UCL Creative Media Services, Mary Hinkley)

The Survey of London’s favourite festive photographs

By the Survey of London, on 21 December 2017

Thank you for taking the time to read the Survey of London’s blog posts over the last year. Here follows a selection of our favourite festive photographs from our past and current studies of the capital’s built environment. Happy Christmas and all good wishes for the New Year.

Oxford Street

The character of Oxford Street is defined above all by its shops, and Christmas is its busiest time of the year. In 2015 we asked Lucy Millson-Watkins to photograph the lights, sights and decorations of Christmas on Oxford Street. Here is a selection of the photographs that she took, first published online in a blog post which considered the festive season on Oxford Street and its enduring traditions.

Oxford Street at dusk, looking east. (© Survey of London, Lucy Millson-Watkins)

Christmas bauble decorations strung across Oxford Street in December 2015. (© Survey of London, Lucy Millson-Watkins)

Boots, with understated decoration. (© Survey of London, Lucy Millson-Watkins)

Whitechapel

Last December it was announced that the Whitechapel Bell Foundry would close in May 2017, and this year has witnessed its closure and the end of what has been a remarkable story. Business cards claim the bell foundry as ‘Britain’s oldest manufacturing company’ and ‘the world’s most famous bell foundry’ – the first not readily contradicted, the second unverifiable but plausible. The business, principally the making of church bells, had operated continuously in Whitechapel since at least the 1570s. It had been on its present site with the existing house and office buildings since the mid 1740s. Derek Kendall’s wintry photographs of the bell foundry in 2010 provide an insight into its historic buildings and the preservation of traditional craftsmanship until its closure. If you would like to read the Survey’s full account, please click here to find the draft text on the Survey’s ‘Histories of Whitechapel’ website.

Shopfront at the east end of 32–34 Whitechapel Road in 2010. (© Historic England Archive, photographed by Derek Kendall)

Inner yard of the bell foundry, looking north-west in 2010. (© Historic England Archive, photographed by Derek Kendall)

Tuning shop in 2010. (© Historic England Archive, photographed by Derek Kendall)

University College London

There is a Survey of London monograph on University College London in the offing. UCL’s first architectural expression was the grand neoclassical building constructed in 1827–9 to designs by William Wilkins, its portico and dome a prominent statement. Only the central range of this scheme was completed, yet successive wing extensions have formed a dignified quadrangle in Gower Street.

The Corinthian portico and dome of the Wilkins Building is instantly recognizable and has been adopted by UCL as its logo. (© UCL Creative Media Services, Mary Hinkley)

View of the Wilkins Building from Gower Street, looking east. (© UCL Creative Media Services, Mary Hinkley)

Even the railings in front of the Cruciform Building, formerly University College Hospital, received a generous helping of snow in February 2009. Alfred and Paul Waterhouse’s triumphant red-brick and terracotta hospital was built on a cruciform plan in 1896–1906. (© UCL Creative Media Services, photographed in 2009 by Mary Hinkley)

Battersea

Clapham Common is one of London’s most-prized public spaces, notable for its wide-open character and the clear sense of definition and urbanity imposed by its boundaries. An essentially triangular and uniform area of some 220 acres, it has lost less ground to development than most metropolitan commons. Archery was a popular pastime in the eighteenth century, as were boxing and hopping matches, and occasional fairs which attracted larger gatherings. Today the common boasts a mixture of formal and informal planting, tree-lined roads, sports facilities, play areas, and broad open spaces. The ponds and the bandstand (1890) are notable remnants of improvements effected in the nineteenth century, when cricket, football, tennis, golf, horse riding, model yachting and bathing were all enjoyed on the common. If you would like to read the Survey’s full account of Clapham Common from the Battersea volumes (published in 2013), please click here to download the draft chapter on ‘Parks and Open Spaces’ from our website.

Clapham Common, the north-western panhandle under snow in 2013. St Barnabas’s Church on Clapham Common North Side is within view in the distance, its pitched roofs adorned by a dusting of snow. (© Historic England, Chris Redgrave)

Sledging on Clapham Common in 2013. (© Historic England, Chris Redgrave)

Clapham Common under snow in 2013, view towards Clapham Common North Side. (© Historic Englnad, Chris Redgrave)

South-East Marylebone

The brick church and lofty spire of All Saints, together with the twin clergy and parish buildings that front it towards Margaret Street, comprise a renowned monument to Victorian religion and architecture. Exuberant and compact, the group was built in 1850–2 by John Kelk to designs by William Butterfield, yet the interior of the church with its painted reredos by William Dyce was not completed and opened till 1859. Butterfield continued to embellish and alter All Saints throughout his lifetime, and it is always regarded as his masterpiece. Among decorative changes to the interior since his death, the foremost were those made by Ninian Comper between 1909 and 1916. Recent restorations have reinforced Butterfield’s original vision of strength, experimental colour and sublimity. A full account of this astonishing church has been published in the Survey’s volumes on South-East Marylebone, published in 2017. Please click here to read the account of All Saints’ Church in the Survey’s draft chapter on Margaret Street.

View of All Saints’ Church, Margaret Street from the west. (© Historic England, Chris Redgrave)

North aisle, looking north-east. (© Historic England, Chris Redgrave)

Nativity scene on the wall of the north aisle. The tilework at All Saints was designed by Butterfield, painted by Alexander Gibbs and executed by Henry Poole & Sons in 1875–6. (© Historic England, Chris Redgrave)

The ‘bijou’ or ‘dwarf’ houses of the Howard de Walden grid. Part 1: the Victorian and Edwardian periods

By the Survey of London, on 24 November 2017

The east–west streets at the northern end of the Howard de Walden Estate in Marylebone – Devonshire Street, Weymouth Street and New Cavendish Street – are notable for the prevalence of a particular building type: the so-called ‘bijou’ house fronting the main street at the corner of a mews, where established rights to light restricted building to two, or at most, three storeys. Sometimes detached, often double-fronted, these smaller houses made a major contribution to the streetscape where there had formerly been only the blank return walls of the big houses in the grander north–south streets like Harley and Wimpole Streets, or their lowly mews additions.

Though this was a predominantly turn-of-the-century phenomenon, there were antecedents. A little house facing Devonshire Street (now 117a Harley Street) had been partitioned out of a corner house on Harley Street (No. 117) by the mid 1840s. In 1855–6 a stuccoed, Regency-style two-storey house was added next door (now 21 Devonshire Street) on the site of a stable building at the corner with Devonshire Mews West, and was imitated twenty years later by a pair in like clothing on former mews plots on opposite sides of Weymouth Street (Nos 36 and 43, of 1870–4). But unlike the later examples, these do not appear to have been part of a conscious trend.

That trend began with Barrow Emanuel, partner in the successful London-Jewish architectural practice Davis & Emanuel. In 1886 he negotiated for a sublease of the old stable block at the rear of a corner house at 90 Harley Street, asking if the Estate would be happy for him to rebuild not with stables but with a small house facing Weymouth Street (now No. 32a). Its success encouraged Emanuel to do likewise in 1894–5 with the similar site opposite, at the rear of 88 Harley Street, where he built another new house (33 Weymouth Street); and he was disappointed in 1898 not to secure a further such plot on New Cavendish Street (No. 55), behind 67 Harley Street, but the fashion had by then caught on, and competition and prices were rising sharply. By that date Emanuel had built a comparable ‘bijou residence’ for his own use at 147 Harley Street (since demolished). No. 114a Harley Street, of 1903–4, erected facing Devonshire Street, seems to be the last of his creations of this type in the area.

The heyday of these mews-side houses was the early 1900s, up to the outbreak of war in 1914, during which period some dozen examples were erected in these three east–west streets. A few more were added in the late 1910s and 20s and then a remarkable group was commissioned by Bovis Ltd in the 1930s from three eminent modern architectural practices: 39 and 40 Devonshire Street (Burnet, Tait & Lorne, 1930–3), 22 Weymouth Street (Sir Giles Gilbert Scott and Adrian Gilbert Scott, 1934–6) and 39 Weymouth Street (G. Grey Wornum, 1935). This says much for the good taste and connections of the Gluckstein and Joseph families, who oversaw the Bovis firm’s rise to prominence in the 1920s and 30s. (These interwar examples will be discussed in more detail in a later blog.)

Stylistically, the red-brick and stone Emanuel-era houses of the 1880s and 90s can be viewed as part of the Queen Anne and neo-Jacobean domestic revival that had proved popular in Kensington for large residences, but here on a more intimate scale. The occasional use of bay windows, porches or asymmetry added to the interest of their façades. Greater variety arrived in the early 1900s when neo-Georgian or freer Flemish styles were also adapted to such plots, and sometimes a more severe Baroque stone-fronted neo-classicism. Such houses were necessarily compact in plan but often offered a more convenient and modern arrangement than the older, bigger terraced house types, all the reception rooms being gathered together at ground-floor level, leaving the upper floor for main bedrooms and bathrooms. As a result they were suited to fewer servants and relatively cheap to run from the domestic point of view. For many turn-of-the-century residents who still preferred a degree of privacy or separation, this was a more attractive alternative to the expensive big houses than the increasingly popular blocks of flats. Though sometimes referred to (inaccurately) as ‘maisonettes’, they were more commonly known at the time as ‘dwarf’ houses, on account of their comparative lack of height.

Adjoining mews-end ‘dwarf’ houses on Weymouth Street: No 34 (right), of 1908 (designed by F. M. Elgood); and No 36, of 1874 (photographed by Chris Redgrave for the Survey of London, © Historic England)

It has been suggested that this crop of stylish ‘dwarf’ houses was an attempt by the Howard de Walden Estate to reintroduce residential use in an area where commerce, medicine and institutions had all but taken over. But the process was driven more by speculators and developers than by the Estate; and though frequently proclaimed as ‘private’ residences, they were more often than not first taken by (and many seem always to have been intended for) medical practitioners as consulting rooms with living space above.

Individual examples:

114a Harley Street dates from 1902 and was the last of the architect Barrow Emanuel’s effective mews corner houses – asymmetrical, partially gabled, in red brick and warm stone, and with a pitched red-tiled roof pierced by dormers. Its first resident in 1905 was Dr Louisa Garrett Anderson (d. 1943), daughter of Elizabeth Garrett Anderson. She was in private practice here as well as working at the women’s hospital on Euston Road founded by her mother, whose social reform agenda she shared, establishing a Women’s Tax Resistance League at this house in 1909. Subsequent practitioners at No. 114a included the neurologist and psychotherapist Dr Hugh Crichton-Miller (d. 1951), founder of the Tavistock Clinic.

21 Devonshire Street, of 1855–6, appears to have been the first purpose-built ‘dwarf’ house in the area. It is a simple two-storey box, but with a subtly arranged, stuccoed front incorporating broad relieving arches to the ground-floor fenestration and a bowed central first-floor window. It was a speculation by the Norwich lawyer Merrick Bircham Bircham, who had recently taken on the lease of 117 and 117a Harley Street, in whose grounds it was built. But Bircham’s lease referred to it as a ‘dwelling and studio’, so it is possible that it was purpose-built for its first resident, the sculptor Joseph Durham, who lived here from 1856 until his death in 1877. Many of Durham’s best-known works would have been modelled here, including his monument to the Great Exhibition (unveiled 1863), now outside the Albert Hall. The iron-and-glass canopy to the entrance is an addition of 1910 by Claude Ferrier.

21 Devonshire Street (photographed by Chris Redgrave for the Survey of London, © Historic England)

38 Devonshire Street is a double-fronted, red-brick mews corner house of 1902–3, given a neo-Elizabethan twist by double-height bays and heavy, stone-mullioned and transomed windows. The architects were Edward Barclay Hoare and Montague Wheeler. Always in medical use, it was recently refurbished by a private dental practice, who added basement seminar rooms. For over ten years in the 1950s–60s, Stephen Ward, the osteopath at the centre of the Profumo Affair, had his consulting rooms at No. 38. No evidence has come to light to support the repeated claim that his client Lord Astor (who gave him the use of a weekend retreat on the Cliveden Estate) bought the house so that Ward, then in financial difficulties, could continue to occupy it rent-free. There were complaints of noisy female guests in Ward’s apartment many years before the scandal erupted in 1963, by which time he had moved with Christine Keeler to a flat in Wimpole Mews, though he continued to practise at No. 38.

38 Devonshire Street (photographed by Chris Redgrave for the Survey of London, © Historic England)

32a Weymouth Street, the first of the area’s late Victorian and Edwardian ‘dwarf’ mews corner houses, was designed by Barrow Emanuel and built in 1886–7 on a site formerly occupied by stabling in Devonshire Mews attached to Nos 90 and 90a Harley Street. Its vernacular Queen Anne Revival style, in red brick with stone dressings, and the two-storey, double-fronted design set the tone for many of the others that followed. Attractive sunflower panels enliven the brickwork and there are carved arabesques to the stone entrance porch and a small monogram (‘BE’) set into the front wall, commemorating the architect. The first residents in the later 1880s and 90s were the cigar importer Arthur Frankau and his wife Julia (née Davis) – better known for her popular novels of London-Jewish life under the pseudonym Frank Danby.

32a Weymouth Street (photographed by Chris Redgrave for the Survey of London, © Historic England)

93a Harley Street (Harley Lodge) is another fine example of the double-fronted mews house rebuildings, this time of the early 1900s. Like its dourer stone-fronted equivalent at 90a Harley Street it was designed in 1911 for the developer Charles Peczenick by Sydney Tatchell, but on this occasion in a more playful red-brick and stone neo-Georgian manner, with a degree of asymmetry within the flanking pedimented end bays. In medical use from the beginning, it is now, like many of its type, a private dental surgery.

93a Harley Street (photographed by Chris Redgrave for the Survey of London, © Historic England)

More of a Baroque air attaches to its neighbour of 1908–10 at 1a Upper Wimpole Street, the work of W. Henry White, with its prominent Flemish-looking gables and giant scrolls. The first-floor window shutters were originally painted green to complement the cherry-red brickwork. The house was a speculation for Samuel Lithgow, the Wimpole Street solicitor and Progressive LCC representative for St Pancras. Its first occupant from 1910 until at least 1937 was Peter Lewis Daniel, a senior surgeon at Charing Cross Hospital, who had a private practice here. Having been in medical use for some time, in 2012 the house was the subject of a high-tech conversion to a five-bedroom family home (by Urban Mesh Ltd).

1a Upper Wimpole Street (photographed by Chris Redgrave for the Survey of London, © Historic England)

55 New Cavendish Street is another of the area’s characteristic mews-side houses, with its stripey red-brick and stone gables, and bows to the front ground-floor drawing and dining rooms. It was built in 1901 to designs by W. Henry White, perhaps reusing an earlier design that he had published in 1888. The developer was the surgeon and cinema pioneer Dr Edmund Distin Maddick.

55 New Cavendish Street (photographed by Chris Redgrave for the Survey of London, © Historic England)

59 New Cavendish Street is a double-fronted ‘dwarf’ house, though here on a more lavish scale, being entirely fronted in Portland stone in a strong Baroque neoclassical style. Set behind a carriage sweep, it has a prominent central entrance porch with a pediment and heavily blocked columns. It was built in 1910 by Kingerlee & Sons to the designs of F. M. Elgood and was another of the speculations in the area funded by the solicitor Samuel Lithgow. The first occupants, there until the 1940s, were Reuben Goldstein Edwards and his wife Edith. He had made a fortune from Edwards’ Harlene hair restorer and colourant. Edith’s philanthropic work later earned her an MBE, and during the First World War their house was given over to the Red Cross Central Workrooms for the production of hospital garments for the wounded. Since the Second World War it has been predominantly in commercial or medical use.

59 New Cavendish Street (photographed by Chris Redgrave for the Survey of London, © Historic England)

The Royal London Hospital Estate: a self-guided walk in Whitechapel

By the Survey of London, on 3 November 2017

The Survey of London would like to share a self-guided walk around the eastern portion of the Royal London Hospital’s estate, bounded roughly by Whitechapel Road north, Cavell Street east, Commercial Road south, and New Road west. Download our route map and guide for a fuller introduction to the history of the hospital and its estate: Guide to a walking tour of the Royal London Hospital Estate

The Royal London Hospital traces its origins to a charitable infirmary established in 1740 for the working poor of east London. Initially based in converted terraced houses in Moorgate and Prescot Street, the institution secured a permanent home with the construction of a purpose-built hospital (1751–78) in open fields on the south side of Whitechapel Road.

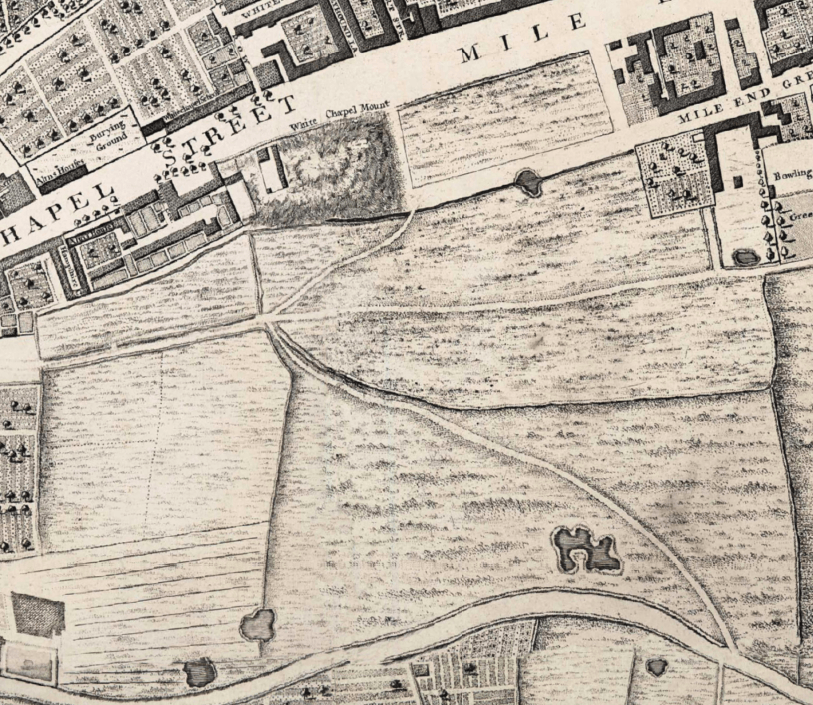

The hospital was built on the rectangular field east of Whitechapel Mount, an artificial hill formed as part of the fortifications built round London in the 1640s. It was bounded by open fields to the south belonging to the Red Lion Farm. (Extract from John Rocque’s map of London c.1746)

One of the attractions of the site acquired by the hospital was its healthy location, bounded to the south by meadows and pastures belonging to the Red Lion Farm on Mile End Green. The medical staff promoted the virtues of fresh air and ventilation around the hospital for the recovery of patients. By 1772 the hospital had acquired roughly thirty acres of fields on the south side of Whitechapel Road, stretching as far south as the present course of the Commercial Road. This large swathe of land protected the hospital from the threat of unwanted encroachment and presented an opportunity to raise funds through building development.

The hospital began to offer land on building leases in the 1780s. Building development was initially confined to the west side of New Road, which had been laid out in the 1750s. The eastern portion of the hospital’s estate was developed in the first half of the nineteenth century in an orderly grid of wide, airy streets. Surviving rows of brick-built terraced houses in Walden Street, Nelson Street, Varden Street and Turner Street point to the tension between the hospital’s estate development and the watchful eye which the medical staff exerted over its vicinity to preserve ventilation.

Aerial view of the London Hospital in the 1930s.

Many of the nineteenth-century terraces built to secure an income for the hospital have been sacrificed for its expansion and success, with the construction of an assortment of medical buildings such as the Outpatients Department (1900–2) and the adjacent Outpatients Annexe (1935–6) in Stepney Way. A remarkable acquisition is the former St Philip’s Church (1888–92), which was converted into a medical and dental library in the 1980s. Despite the concentration of buildings associated with the Royal London Hospital in the area, there are a few interlopers, including the bulky East London Mail Centre (1970), the Good Samaritan Public House (1937–8), and Gwynne House (1937–8). The south end of the estate has resisted the march of medical buildings, and the Nelson Street Synagogue and a former Baptist chapel in Varden Street testify to Whitechapel’s diverse patterns of immigration.