Winstanley Estate, Battersea

By the Survey of London, on 29 January 2016

Social housing has been much in the news lately with the Government’s controversial plans to ‘blitz’ what are considered ‘sink’ estates.

‘David Cameron promises to bulldoze Britain’s sink estates’, The Daily Mail, 10 January 2016

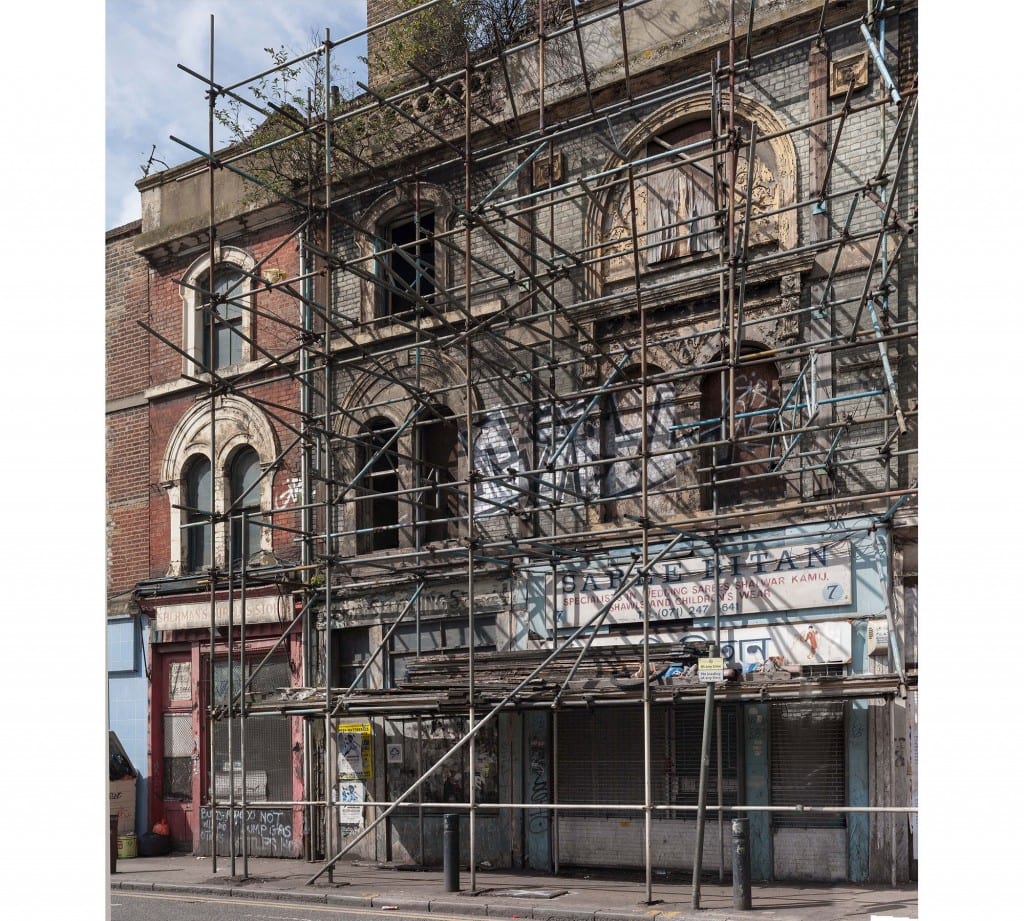

One of those said to be earmarked for redevelopment is the Winstanley Estate, north of Clapham Junction, considered a model of its kind when it went up, mostly in the early to mid-1960s. In fact the area involved includes the slightly later York Road Estate which is likely to be entirely rebuilt, following consultation between Wandsworth Council and local residents.

Winstanley Estate, looking north-west from Thomas Baines Road towards Clark Lawrence Court in 2012 (© English Heritage, Chris Redgrave). If you are having trouble viewing images, please click here.

Winstanley Estate, Thomas Baines Road, photographed in 2012 (© English Heritage, James O. Davies).

The history of the area, its Victorian prehistory of small terraced houses as well as the colourful evolution of the Winstanley and York Road estates from the 1950s to the 1970s were covered in detail in the Survey of London’s volume 50 on Battersea housing (2013). Its assessment generally draws out the relative merits of the Winstanley, with its ‘coherence of design lacking in any other post-war housing built in Battersea’, which is likely to be refurbished, and the ‘uninspired’ York Road with its ‘bulky monotony’, which is to be demolished:

Chapter 8: North of Clapham Junction, draft chapter of Survey of London Volume 50

Clark Lawrence Court in the Winstanley Estate, photographed in 2012 (© English Heritage, James O. Davies).

York Gardens and Pennethorne House, York Road Estate Stage 1, photographed in 2011. Pennethorne House is one of the blocks that is likely to be demolished (© English Heritage, Nigel Corrie).

Though now perhaps best known outside Battersea as the home of garage and hip hop band So Solid Crew, the Winstanley has also provided a filming location for a number of feature films, notably Poor Cow (1967), Ken Loach’s first full-length film as a director, and the Oliver Reed thriller Sitting Target (1972). The Survey was involved with the architecture departments at Cambridge and Liverpool in 2012-13 in a research project called Cinematic Geographies of Battersea. Taking its cue from Jonathan Raban’s 1974 book Soft City, the project explored the different ways that urban histories, such as the Survey, and filmmakers, present the city, whether as the ‘hard city’ found in statistics and maps, or the ‘soft city’ found in the suggestive discontinuities of film. One outcome was a short film about the Winstanley that mixes a voiceover taken from edited Survey of London text about the Winstanley, with archive photos and film clips of the Winstanley, both from newsreel and feature films, to suggest that these hard and soft cities are on a continuum, and not that one is ‘more real’ as Raban suggested, than the other.

The Winstanley Plays Itself by Aileen Reid on Vimeo.

Thomas Baines Road, Winstanley Estate, concrete mural of 1963-5 by William Mitchell & Associates, photographed in 2011 (© English Heritage, James O. Davies).

Close

Close