INTERVIEW: The Sun Sets in the East

By Borimir S Totev, on 14 August 2017

Authors of the film “The Sun Sets in the East”, Agne Dovydaityte (left) and Alexander Belinski (right).

Agne Dovydaityte (A.D.) and Alexander Belinski (A.B.) in conversation with the Executive Editor of SLOVO Journal, Borimir Totev, about the passion for cinema, the Lithuanian country side, an old diary, and their first documentary film project entitled “The Sun Sets in the East”.

How did you end up on the path towards documentary film making? Did you encounter a turning point or a moment of clarity?

A.D.:

I came to London in 2014 to study Journalism, while working as a bartender in one of Angela Hartnett’s restaurants on the side. I wanted to be a journalist since I was five years old, and I’ve always envisioned myself to be involved in print or online media, with a focus on Eastern European culture and politics. However, as someone who has high expectations, I found Journalism studies rather boring and disappointing. I met Alex at university and consequently was introduced to avant-garde cinema, cinematography, and film production. I also began practising Russian with him. Initially we collaborated on video projects for university, then for the hospitality industry, also filming some events and conferences. We felt rather comfortable working with each other – him as a camera person and editor, and me as a producer.

A.B.:

I was born in Ukraine and lived in Germany for a short while, before moving to the United Kingdom. After finishing secondary school, uncertain as to whether I was more interested in politics or communication, I decided to study Journalism at university, where I met Agne. I have been interested in film for a long time. What started out as regular watching of films gradually turned into a passion, perhaps even an obsession with what cinema as a concept had to offer. Inevitably I found myself at a point where things I watched rarely satisfied me anymore, and I therefore developed a desire to create, based on all that I had learned along the way. I didn’t necessarily pick documentary cinema as the format to pursue, and I am very much open to narrative cinema as well, however this is what I’m currently doing. Having said that, I believe the highest form of cinema is a kind of hybrid of documentary and narrative formats.

On one of your trips back to Lithuania you stumbled across an exciting discovery. Tell us more about what inspired “The Sun Sets in the East”?

A.D.:

When I discovered my grandfather’s diary and mentioned it to Alex, we came to a natural realisation that it was a valuable document, telling of moral values and a pastoral lifestyle that is all but forgotten in the ‘developed’ world. We also realised that it would make for an interesting documentary. The diary of my grandfather described the slow and simple life of a peasant in 1984 Soviet Lithuania, in a very delicate and touching manner. Contrary to what some might expect, it is not an emotional diary, he wasn’t a person who experienced loads of suffering, he wasn’t deported, he did not get lost in the stream of history. It is a diary of the everyday life of a peasant, who wakes up in the morning and goes to weed furrows or cut trees in the park. Politics barely reaches him, and he allows himself to seek God, also in a very non-emotional way – simply living by the rules, following church orders, and being a good person. My grandfather, Jonas, writes in a very natural way, non-professionally, rather objectively, makes many mistakes, and uses old Lithuanian, sometimes Russian slang too. He was a very religious person, and went to church a few times a week, noted how many people attended the service, as well as how many pupils and teachers showed up. In Soviet Lithuania, teachers and state workers were not allowed to attend mass. At one point Jonas writes: “Kurtimaitis, a school teacher was buried with the Church, therefore none of the school staff attended. The priest said that other believers have to fill up this gap and pray to God for everyone.” Modern day Lithuania has unfortunately become the leading European country in suicide rates, especially within rural communities. Life there is slow and not everyone can handle this sort of pace. For this reason we believe that now is an appropriate time for a film like ours. Although the diary itself appears to be of a very religious nature, this does not necessarily set the tone for the film.

Where exactly are you in the process of making the film right now and what can we expect to see as a finished product?

A.B.:

At the moment we are alternating between pre-production and principal photography. The film is as planned out as can be for a haphazard project of this nature. It is partially funded, and we hope to close the gap soon with a crowdfunding campaign. Recently, we were in Lithuania for a week, in order to shoot the summer segment of the diary, with the help of friends and relatives acting as chauffeurs and guides. This segment is now being edited, so in a way we are also stepping a little into post-production territory too.

A.D.:

I am mostly responsible for the organisational part of the film – PR, social media, human resources, timing, and planning. We both have a clear vision of how the film is going to look, and we’ve already started shooting it. The visuals mostly show countryside Lithuania, lone villages and houses, fields of barley and hay, with industrial buildings and constructions disturbing this peaceful scenery. Where before there used to be allotments, now there are factories, the landscape is divided by electricity pylons and giant industrial chimneys. These visuals are combined with a voiceover of the diary. Without spoiling too much, we can say that this film will be straightforward, and non-judgemental, with a focus on aesthetics. It simply showcases how the life of a regular Lithuanian peasant looked like, and the landscape in which it unfolded. This is not a film about Lithuania. This is a film about a man at a certain period of history where nothing was certain, apart from one’s faith and nature. Most of what is told by him and shown by us is applicable everywhere and always.

Where would you position documentary film within wider society, how much power does the medium of film generally posses, is it a means to an end?

A.B.:

Documentary film occupies a kind of middle ground between regular mainstream cinema, and more esoteric ‘art house’ cinema. Documentary cinema is not without its own mainstream entrapments, and the ratio of truly unique and challenging documentaries is probably around the same as regular narrative cinema and ‘art house’ cinema. In what I would consider to be the upper echelons of cinema as an art form, there is a great deal of overlap between documentary and narrative cinema, to the extent that one may become indistinguishable from the other. Film is a tremendously powerful medium, both politically and financially. Precisely this power is what has hampered the progress of cinema as an art form. Almost immediately after its inception, cinema was exploited around the world – for financial gain in the West, and for propaganda in the East. Eventually the two systems collided, and much of world cinema became an ugly amalgamation of both models. It’s notorious effectiveness is an unfortunate testament of its ability to have an effect on people. In that regard, in a cynical manner, it is indeed a means to an end. But it shouldn’t be. ‘Real’ cinema, that is, as an art form, is a means unto itself. However, whether that stage will ever be reached universally – I cannot say.

Those interested in the “The Sun Sets in the East”, willing to give advice, financial support, or ask further questions can stay updated via the film’s official Instagram account @eastern.sunset

Flora Murphy: Bolotnaia Five Years On

By Borimir S Totev, on 4 August 2017

Flora Murphy, author of ‘Bolotnaia Five Years On: Can Online Activism Effect Large Scale Political Change in Russia?’.

Flora has just completed her undergraduate degree in Russian with German at University College London. Studying the Russian language from scratch has had a very strong influence on her interests, starting with the language itself initially, and later moving far beyond into politics, culture and everything in between. From learning Russian, Flora got into making documentaries and during her time at UCL, she made two films about the ongoing conflict in Eastern Ukraine and one documentary about the LGBT community in Moscow. When she was on a year abroad in Moscow, Flora learned more about internal Russian politics by interning at TV Rain, arguably Russia’s only non pro-government television channel. Her interest in the ideas of modern propaganda in Russia and restrictions on freedom of speech was the starting point for the SLOVO published article about the opposition’s use of the internet as a tool for resistance in Russia. In the near future, Flora plans to travel more extensively in the post-Soviet region, especially in Moldova, Georgia and the Central Asian countries, perhaps making some more films along the way. Her further interests include organised crime, conflict management, and security issues. Flora is set to be in St Petersburg from late September until Christmas, trying to keep up her language skills and to complete a short translation internship.

Flora’s article explores the role of new media in Russian politics and ultimately argues that their potential to bring about significant political change in the current Russian political landscape is limited. The 2011-2012 winter protests, in Bolotnaia Square in Moscow and across Russia, led to a boom in both Russian and English-language protest scholarship, especially regarding the role that new media and online communication networks play in the organisation and execution of political movements. But the significance of her case study is not limited to Russia: this question must be understood in a global context. In a post-Arab Spring world, this topic is one of active discussion and current global relevance. Her paper aims to consider the Russian case study in that broader context, bridging gaps in existing scholarship in this field.

The article ‘Bolotnaia Five Years On: Can Online Activism Effect Large-Scale Political Change in Russia?’ by Flora Murphy (School of Slavonic and East European Studies, University College London) was published in SLOVO Journal, VOL 29.1, and can be read in full here.

Posted by Borimir Totev, Executive Editor of SLOVO Journal

Andreea Mironescu: Quiet Voices, Faded Photographs

By Borimir S Totev, on 3 August 2017

Andreea Mironescu, author of ‘Quiet Voices, Faded Photographs: Remembering the Armenian Genocide in Varujan Vosganian’s The Book of Whispers’.

Andreea has been a Researcher at the Department of Interdisciplinary Research in Social Sciences and Humanities, “Alexandru Ioan Cuza” University of Iasi, Romania since 2013. She obtained a PhD in Philology in 2012. Andreea has also been a postdoctoral fellow of the Romanian Academy during 2014 and 2015, with a focus on the theme of the relationship between literature and cultural memory in post-Communist Romania. She is currently an invited researcher in the project “Erinnern and Vergessen in Posttotalitarismus: Kulturelles Gedächtnis–Ästhetisches Erinnern” (Remembering and Forgetting in Posttotalitarianism: Cultural Memory-Aesthetic Remembrance), Humboldt University of Berlin. Her domains of interest are Romanian modern and contemporary literature, post-Communism, memory studies, and East-Central European literary cultures.

Drawing on concepts such as post-genocide literature, postmemory (Marianne Hirsch), and resonance (Aleida Assmann), Andreea’s article discusses a third-generation narrative of the Armenian genocide, namely Varujan Vosganian’s novel The Book of Whispers, originally published in Romania in 2009. The first section of the paper examines whether the concepts of post-genocide literature and diasporic literature (Peeromian) can be applied to authors of Armenian origins writing inside the literary traditions of East-Central European national cultures. The second section analyses the literary techniques of inter-generational memory transmission in Vosganian’s novel. Particular attention is paid to the way in which family and documentary photos are employed in the novel, and three functions of photographs are discussed in relation with autobiographical memory, historical representation, and literary aesthetics. The third part of the paper uses Assmann’s concept of resonance to investigate how the Armenian genocide narratives are linked with other traumatic events such as the Holocaust, the mass deportations in the Soviet Gulag, or the political repression in Romanian totalitarianism, thus reshaping the European memory of violence.

The article ‘Quiet Voices, Faded Photographs: Remembering the Armenian Genocide in Varujan Vosganian’s The Book of Whispers’ by Andreea Mironescu (The Department of Interdisciplinary Research in Social Sciences and Humanities, ‘Alexandru Ioan Cuza’ University of Iasi) was published in SLOVO Journal, VOL 29.2, and can be read in full here.

Posted by Borimir Totev, Executive Editor of SLOVO Journal

Genevieve Silk & Cúshla Little: Nightmare on Garibaldi Street, Miracles for Dummies

By Borimir S Totev, on 1 August 2017

Genevieve Silk (right) and Cúshla Little (left), authors of the translations of stories by Irina Luk’ianova.

Genevieve just completed her degree in French and Russian, which she studied alongside Czech, and will be starting an internship in Prague from September, after which she plans to spend some time working in Russia. Cúshla has also just completed her degree in French and Russian, and will soon be moving to St Petersburg to teach English, and further study the Russian language.

Genevieve and Cúshla have translated two stories by Irina Luk’ianova, one of Russia’s foremost writers. Originally from Novosibirsk, Irina moved to Moscow in 1996, where she now lives. Her work spans journalism, blogging and creative writing. Irina’s fiction exhibits psychological acuity often laced with irony and humour, but there is always a human warmth to her writing. The two stories translated and published in SLOVO Journal VOL 29.2 are ‘Nightmare on Garibaldi Street’ and ‘Miracles for Dummies’, first appearing in the Russian daily newspaper New Gazette in 2009.

The translation of ‘Two Stories by Irina Luk’ianova‘ by Genevieve Silk (University of Bristol) and Cúshla Little (University of Bristol) was published in SLOVO Journal, VOL 29.2, and can be read in full here.

Posted by Borimir Totev, Executive Editor of SLOVO Journal

Türkan Olcay: A Russian Orientalist and Translator Enchants the Ottomans

By Borimir S Totev, on 31 July 2017

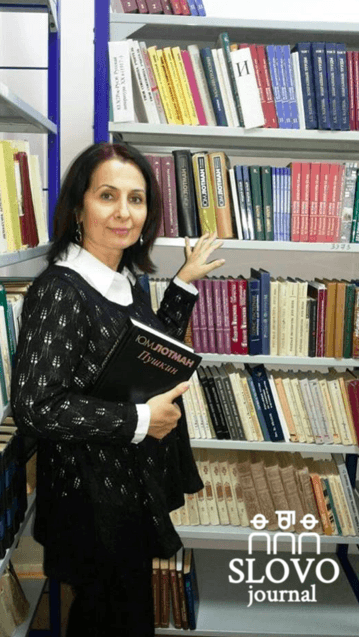

Türkan Olcay, author of ‘Olga Lebedeva ( Madame Gülnar): A Russian Orientalist and Translator Enchants the Ottomans’.

Türkan’s fields of specialisation are 19th century Russian literature, Turkish-Russian cultural and literal relations, as well as the contribution of Russian emigrants to the cultural life of Istanbul in the 1920’s. Her published works include a wide range of articles on Russian literature on the Turkish scene, Chekov’s plays on the Turkish scene, and Russian traces on the Istanbul scene, amongst many others. In addition to her published works, Türkan has accumulated an in-depth teaching experience from 1994 to the present. Türkan Olcay is currently working on projects concerning the history of Russian literary translations in Turkey from 1884 to the present day, as well as being a foreign participant in the project “Russian Literature in the World Context” by The Gorky Institute of World Literature.

Based on the studying of a number of archive and scientific literature sources, Türkan’s article attempts to research the life and works of the first Russian female orientalist Olga Sergeevna Lebedeva. Under the pseudonym ‘Gülnar’, she was one of the first to introduce the Turkish reading public to the treasures of Russian literature, thus making an invaluable contribution to Turkish–Russian literary connections at the end of the nineteenth century. A special place in the article is devoted to Olga Lebedeva’s translations and literary critical studies in the Ottoman Empire in 1890s and also interrelationship between her and the prominent Ottoman writer and publisher Ahmet Mithat Efendi.

The article ‘Olga Lebedeva ( Madame Gülnar): A Russian Orientalist and Translator Enchants the Ottomans‘ by Türkan Olcay (Istanbul University) was published in SLOVO Journal, VOL 29.2, and can be read in full here.

Posted by Borimir Totev, Executive Editor of SLOVO Journal

Elliott Chandler: You Carry Me

By Borimir S Totev, on 28 July 2017

You Carry Me (Ti Mene Nosiš, 2015) is a film produced in Croatia, which originally aired as a television series, Da sam ja netko (If I Were Someone). Ti Mene Nosiš is available on Netflix as You Carry Me (2016) with subtitles in five languages. The purchase of the rights to You Carry Me by Netflix is among the film’s many successes. Other successes include the naming of Ivona Juka as ‘the laureate in the film section […] writing and directing her feature debut.’ The dialogue is a colourful Zagrebtonian language with traditional Balkan passion. Dora, Ives and Nataša face deteriorating relationships with their fathers: Neglected Dora is reunited with her father in the text; Ives is struggling to care for her father, Ivan, who has Alzheimer’s; and Nataša, who is pregnant, comes face-to-face with the father who abandoned her. The director identifies father-daughter relationships as the most significant aspect of the film. The plot centres on changing relationships between men and women, between fathers and daughters, and also between husbands and brothers. These are complex stories, and they are wrapped in some wonderful cinematography that showcases admirable storytelling and affective symbolism.

To read more reviews, visit Elliott’s blog here. Elliott is an English Literature graduate, and is interested in history, romanticism, and Serbo-Croat culture.

The film review for ‘Ti Mene Nosiš/You Carry Me’ by Elliott Chandler (The School of Slavonic and East European Studies, University College London) was published in SLOVO Journal, VOL 29.1, and can be read in full here.

Posted by Borimir Totev, Executive Editor of SLOVO Journal

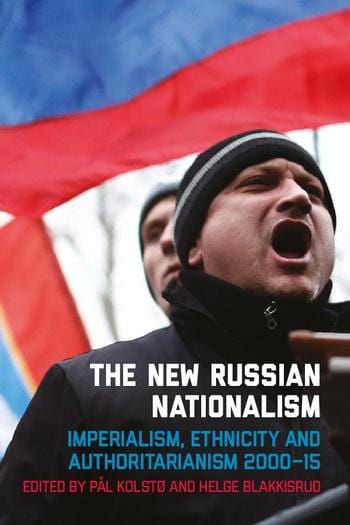

Rachael Horwitz: New Russian Nationalism

By Borimir S Totev, on 27 July 2017

Rachael Horwitz, author of the book review of ‘The New Russian Nationalism: Imperialism, Ethnicity and Authoritarianism 2000-2015’.

Rachael is an IMESS student at the School of Slavonic and East European Studies, University College London studying Politics and Security. She is going to Moscow at the end of August as part of her programme’s second year. Rachael is interested in nationalism and the Ukrainian conflict, and is hoping to pursue a PhD in the field. She is a keen writer and loves watching films, outside of academia, Rachael enjoys horror and science fiction. To discover more of Racahel’s fiction writing, visit her blog here.

Her book review publ ished in SLOVO Journal VOL 29.2 discusses the 2016 study of ‘new’ strains in Russian nationalism and their relationship with the Russian state, as well as influence on public opinion. The study looks at how nationalism has impacted various aspects of contemporary Russian life, from attitudes towards the church to views on migrants. This useful and timely volume covers the growth of Russian nationalism from 2000 to 2015. It was in the process of completion during the annexation of Crimea in March 2014 and thus most of the chapters refer largely to events prior to that date, with some analytical coverage of how Russian nationalism has shaped public opinion of the annexation and subsequent Eastern Ukrainian conflict. It is thoroughly researched and yet accessible to the general reader, though with a few minor issues. The collection aims to explore the different currents within contemporary Russian nationalism, analysing their complex relationship with the state and Russian society. It is an anthology, with different chapters, which offer contrasting and sometimes contradictory perspectives on the issue of Russian nationalism. The book is divided into two main sections, with the first describing what Kolstø calls ‘society-level’ Russian nationalism, while the second is devoted to nationalism at state level and the changing discourse of Putin and the state in relationship to national identity. The final chapter is a discussion of nationalist economic policy in Russia and the debate at the state level between adopting protectionist policies or a more globalised economic model. This echoes current discussions in the West over pro-business policies such as privatisation, which have been blamed for creating a ‘left-behind’ class and fuelling sympathies for nationalist rhetoric, and underlines that Russia faces many of the same issues as Western countries in its approach to these issues.

ished in SLOVO Journal VOL 29.2 discusses the 2016 study of ‘new’ strains in Russian nationalism and their relationship with the Russian state, as well as influence on public opinion. The study looks at how nationalism has impacted various aspects of contemporary Russian life, from attitudes towards the church to views on migrants. This useful and timely volume covers the growth of Russian nationalism from 2000 to 2015. It was in the process of completion during the annexation of Crimea in March 2014 and thus most of the chapters refer largely to events prior to that date, with some analytical coverage of how Russian nationalism has shaped public opinion of the annexation and subsequent Eastern Ukrainian conflict. It is thoroughly researched and yet accessible to the general reader, though with a few minor issues. The collection aims to explore the different currents within contemporary Russian nationalism, analysing their complex relationship with the state and Russian society. It is an anthology, with different chapters, which offer contrasting and sometimes contradictory perspectives on the issue of Russian nationalism. The book is divided into two main sections, with the first describing what Kolstø calls ‘society-level’ Russian nationalism, while the second is devoted to nationalism at state level and the changing discourse of Putin and the state in relationship to national identity. The final chapter is a discussion of nationalist economic policy in Russia and the debate at the state level between adopting protectionist policies or a more globalised economic model. This echoes current discussions in the West over pro-business policies such as privatisation, which have been blamed for creating a ‘left-behind’ class and fuelling sympathies for nationalist rhetoric, and underlines that Russia faces many of the same issues as Western countries in its approach to these issues.

The book review for ‘The New Russian Nationalism: Imperialism, Ethnicity and Authoritarianism 2000-2015‘ by Rachael Horwitz (The School of Slavonic and East European Studies, University College London) was published in SLOVO Journal, VOL 29.2, and can be read in full here.

Posted by Borimir Totev, Executive Editor of SLOVO Journal

Aron Kerpel-Fronius: Pole and Hungarian Cousins Be?

By Borimir S Totev, on 26 July 2017

Aron Kerpel-Fronius, author of ‘Pole and Hungarian Cousins Be? A Comparison of State Media Capture, Ideological Narratives and Political Truth Monopolization in Hungary and Poland’.

Aron is a Hungarian post-graduate student at the flagship IMESS programme at University College London, studying Economics and Politics. He is set to spend the next academic year at the Jagiellonian University in Krakow. Aron’s main research interests include illiberal parties and civil societies of EEA, particularly within the Visegrad group. Aron is also planning to pursue a PhD programme in the same field next year. Currently, he is an intern at Transparency International Hungary, and from next month, will be starting another internship in Krakow’s Kosciuszko Institute, a Polish think tank specialising in cyber security, using this opportunity do deepen his knowledge on Polish language and culture.

Public discourse is shaped through various factors; in his article, Aron focuses explicitly on the two governments’ treatment of the media landscape, as it is the biggest and most effective platform for this purpose. The paper argues that both Fidesz and PiS are attempting to capture the state and private media, using these to propagate their political ideology. Thus by monopolising media discourse and portraying themselves as the representatives of the people on all three symbolic levels, the two governments attempt to discredit any civil or parliamentary opposition group, and emerge as the sole central political force domestically. The aim of the paper is to compare the extent to which the Fidesz and PiS government managed to succeed in this attempt to the present day.

The article ‘Pole and Hungarian Cousins Be? A Comparison of State Media Capture, Ideological Narratives and Political Truth Monopolization in Hungary and Poland’ by Aron Kerpel-Fronius (The School of Slavonic and East European Studies, University College London) was published in SLOVO Journal, VOL 29.1, and can be read in full here.

Posted by Borimir Totev, Executive Editor of SLOVO Journal

Ruxandra Petrinca: Halfway Between Memory and History

By Borimir S Totev, on 24 July 2017

Ruxandra is a historian working on the Communist and Post-Socialist periods. She holds a LL.B and an M.A. in Canadian Studies from the University of Bucharest. After her arrival in Montreal in 2006, she pursued a double specialisation B.A. in English and History, and an M.A. in History at Concordia University. Currently, Ruxandra is a PhD candidate, ABD, with the Department of History and Classical Studies at McGill University, working under the joint supervision of Prof. Catherine LeGrand and Prof. Lavinia Stan (St. Francis Xavier University). Ruxandra’s main research interests include manifestations of dissent and resistance in Communist states. Her thesis examines the evolution and social transformation of the Romanian communities of 2 Mai and Vama Veche as alternative cultural spaces inside an authoritarian regime. Ruxandra is also interested in public memory, propaganda, the role of intellectuals in shaping the transition to democracy in former Communist states, youth sub-culture, socialist film discourse, and radio propaganda. Previous publications by Ruxandra Petrinca include, “Smoke Screens and Liminal Spaces in Socialist Romania: Legacy, Diversity, and Cultural Dissent on the Shores of the Black Sea”, “When Postmodernism Met Authoritarian Socialist Discourse”, review of Sahia Vintage I, Documentary, Ideology, Life, “Choosing to Forget: Politics, Family, and Everyday Life in Stalinist Romania”, and “Recuperating the Communist Past, Romanian Literature and Authoritative Discourse”. For more by Ruxandra, you can view her Academia.edu profile here.

Ruxandra’s article in SLOVO Journal analyses a sample of seven Gulag memoirs that recount experiences of imprisonment at the height of the Stalinist repression in Romania, between 1947 and 1964. The paper looks at the literary conventions employed by the authors in the recounting of their stories. The memoirs were chosen for the broad range of perspectives they represent, with particular attention being paid to the gendered experiences of imprisonment. The texts are approached through the lenses of literary criticism, as the article analyses common tropes, motifs, characters, and techniques of narration – elements that make Gulag memoirs a ‘genre’ in its own right. A close reading of the text will uncover not only the gruesome realities of Communist persecution, imprisonment, and torture, but also the prevailing mentalities of that era. The literary components of the texts provide clues that help in decoding the authors’ self and their understanding of history.

The article ‘Halfway between Memory and History: Romanian Gulag Memoirs as a Genre’ by Ruxandra Petrinca (McGill University, Montreal) was published in SLOVO Journal, VOL 29.1, and can be read in full here.

Posted by Borimir Totev, Executive Editor of SLOVO Journal

Nadège Mariotti: Between Physical Performance and Instrumentalisation

By Borimir S Totev, on 20 July 2017

Nadège Mariotti, author of ‘A.G. Stakhanov in Gaumont Pathé’s Soviet Film Archives: Between Physical Performance and Instrumentalisation’.

Nadège Mariotti is a Professor and instructor in History at the University of Lorraine since 2002. She trains future teachers within the framework of a professional Master’s Degree in Education. For several years Nadège has been developing training sessions about the didactic approach to images. As a PhD student at the Paris Sorbonne New University since 2012, her research focuses on the representations of the world of mining and steelwork, through to the technical gesture in animated images from the end of the 19th century to the end of the Thirty Glorious Years (1975).

Nadège’s article examines the evolution of the memory of Stakhanov’s record mining achievement, moving from a retrospective point of view to a celebration, and finally to commemoration. The depiction of the miner A.G. Stakhanov in newsreels from the Gaumont Pathé archives highlights the representations of this physical performance used in the specific economic and political environment of the USSR during the interwar period. The Soviet worker is idealised as a national hero. At that time, the Soviet government was looking for the “New Man” and “new technical standards” and Stakhanov lost his individuality, becoming “only an official agent of the state”.

The article ‘A.G. Stakhanov in Gaumont Pathé’s Soviet Film Archives: Between Physical Performance and Instrumentalisation’ by Nadège Mariotti (University of Lorraine, University of Sorbonne Nouvelle) was published in SLOVO Journal, VOL 29.2, and can be read in full here.

Posted by Borimir Totev, Executive Editor of SLOVO Journal

Close

Close