Iglika Grebenarova: Revolution

By Borimir S Totev, on 17 July 2017

Iglika is a student at the New York University, majoring in International Relations and minoring in Cinema Studies, set to graduate in May of 2018. She is passionate about European affairs, and the intersection between cinema and politics, as well as art’s ability to both reflect and form ideological discourse. As well as being an intern at the Ayn Rand Institute in June 2015, Iglika has interned for the Bulgarian Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Center for the Study of Democracy. Other parts of Iglika Grebenarova’s research has previously focused on 60’s European cinema, Romanian New Wave, and Film Festival Politics.

In her film review for SLOVO Journal, Iglika focuses on Director Margy Kinmonth’s latest film as the pinnacle of her exploration of the secrets of Russian art spanning over more than three decades. Revolution: New Art for a New World is a spectacular documentary made to commemorate the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 and to demonstrate the crucial importance of art for the creation of the new regime. With the remarkable breadth and depth of its scope, the film creates an exhilarating depiction of one of modern history’s most tumultuous periods and immerses its viewers into the inseparable mixture of art and politics that shaped humanity’s future for decades to come.

The film review for ‘Revolution: New Art for a New World‘ by Iglika Grebenarova (New York University, NYC) was published in SLOVO Journal, VOL 29.1, and can be read in full here.

Posted by Borimir Totev, Executive Editor of SLOVO Journal

Ksenia Pavlenko: A Pause in Peripheral Perspectives

By Borimir S Totev, on 15 July 2017

Ksenia Pavlenko, author of ‘A Pause in Peripheral Perspectives: Sergei Diaghilev’s 1898 Exhibition of Russian and Finnish Art’.

Ksenia is the Website and Social Media Manager and a member of the Advisory Board for the Cambridge Courtauld Russian Art Centre. She is an MPhil candidate in History of Art at the University of Cambridge, supervised by Dr. Rosalind Polly Blakesley, researching the visual culture of Finland as a Grand Duchy of the Russian Empire. Her studies extend from the establishment of Helsinki as a capital city in the early nineteenth century, to Finnish participation in early twentieth century artistic developments on an international scale. Ksenia completed her BA in History of Art and English Literature at the City University of New York in 2013, after which she worked for institutions such at the International Center of Photography and American Federation of Arts.

Ksenia’s SLOVO Journal article examines three years of monumental change in Finnish-Russian cultural relations at the fin de siècle. The territory of Finland had enjoyed autonomy and economic development for the greater part of the nineteenth century as a Grand Duchy of the Russian Empire. Sergei Diaghilev’s 1898 Exhibition of Russian and Finnish Art exemplifies how this positive dynamic began to manifest itself in transcultural exchange. Diaghilev sought for Russia’s creative circles to follow the Finnish example of engaging with Western European artistic developments while refining a distinct national vision. Such a dynamic would have appeased imperial interests in promoting its Russian heritage while allowing Finns to continue to express their distinct culture. The Russification Programme, initiated in 1899, changed an amicable relationship between the Russian Empire and its Finnish territory to one of oppression. The rich cultural heritage Finnish intellectuals had developed throughout the nineteenth century was quickly mobilised to resist imperial oppression, exemplified in the Finnish Pavilion at the 1900 Paris Exposition Universelle. The collaborative potential of Diaghilev’s 1898 exhibition was replaced by a resounding call for Finnish autonomy at the 1900 Finish Pavilion. The period of 1898-1900 demonstrates how quickly Finland’s embrace of nineteenth-century nationalism transformed from a cultural blossoming to a politicised quest for autonomy.

The article ‘A Pause in Peripheral Perspectives: Sergei Diaghilev’s 1898 Exhibition of Russian and Finnish Art’ by Ksenia Pavlenko (University of Cambridge) was published in SLOVO Journal, VOL 29.1, and can be read in full here.

Posted by Borimir Totev, Executive Editor of SLOVO Journal

We Are Not Bargaining Chips

By Borimir S Totev, on 25 April 2017

The recent raptures surrounding the futures of the Central European University in Budapest and the European University at St. Petersburg have deservingly catered for the creation of a renewed sentiment of solidarity amongst a worldwide web of academics, higher education institutions and organisations defending academic freedom, any by extension, the freedom of thought.

SLOVO Journal, here at the UCL School of Slavonic and East European Studies, joins in with the effort to safeguard our fellow colleagues, struggling in the face of oppressive policies. We would like to extend UCL’s invitation to our readership and welcome all those who believe that freedom of thought should not be subservient to state boundaries or illiberal mandates of power. Thought is timeless, the rest – not so much.

We, the people who think, are never to be used as bargaining chips.

Meet us on the 26th April 2017, be by the main UCL Quad, in front of the Portico, where speeches from leading UCL Academics will take place.

By Borimir Totev, Executive Editor of SLOVO Journal

So Far, So Good, So SLOVO

By Borimir S Totev, on 17 April 2017

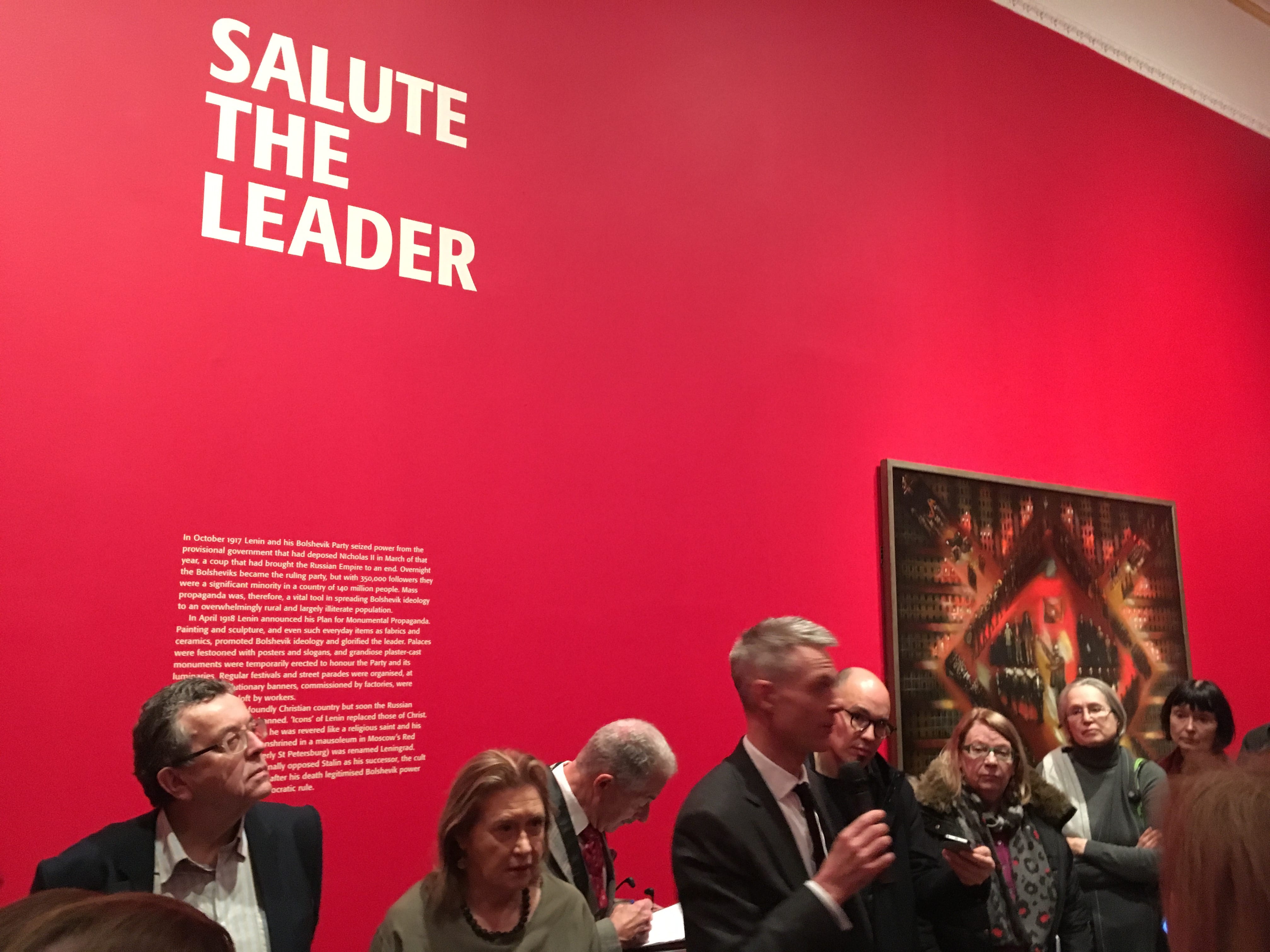

Today the Royal Academy of Arts ends its exhibition on Russian art in the period of 1917-1932. The much celebrated works of Malevich, Petrov-Vodkin, Kandinsky, and Chagall, amongst many others, remained open to visitors of the Main Galleries for more than two months. Back in February, SLOVO Journal was invited to the Press Viewing of the exhibition supplemented by a tour with the curators Ann Dumas, Dr Natalia Murray, and Professor John Milner.

It was made obvious to me then, that a season of appreciating Russian art was slowly about to unravel in our country’s capital, and with its cultural calendar London fully embraced the task of marking one of the most profound and consequential moments in world history. However, much in contrary to what some critiques suggest about the centenary of the Russian Revolution, I contend that its acknowledgment here was done elegantly, with an accurate awareness of history and its plights.

We are now almost half way through the year. So far, so good. Fear not, there is still plenty out there to see, explore, and read on the topic of all things Russian.

For starters, if you haven’t done so already, make sure to read through the latest issue of SLOVO Journal available online, or rummage through our collection of electronic archives. For nearly three decades we have provided a platform for the publication of promising academic work covering the Russian, Post-Soviet, Central & East European regions. In VOL 29.1 published in January this year, our authors covered intellectually stimulating explorations of human testaments to past events and cultural relations, as well as the more contemporary topics of online activism in Russia and the revival of populism in Europe.

There is still some time left before our 1st May deadline to submit your own papers and reviews for consideration. The publication of VOL 29.2 will complete our annual run marking the centenary year of the Russian Revolution and will be published around the autumn season of 2017.

Don’t forget to keep an eye out for the events that are constantly taking place at UCL’s School of Slavonic and East European Studies. Back in March, SLOVO Journal screened the feature documentary ‘Revolution: New Art for a New World’ as part of SSEES’s events calendar, hosting BAFTA Award wining filmmaker Mary Kinmonth.

What else is left? Plenty. The Design Museum is in the middle of its ‘Imagine Moscow’ exhibition exploring Moscow as it was imagined by a new generation of bold and creative architects and designers. The launch of the new book ‘The Sixth Sense of the Avant-Garde: Dance, Kinaesthesia and the arts in Revolutionary Russia’ by Irina Sirotkina and Roger Smith will take place on the 18th May at the Calvert 22 Bookshop. Film fans can look forward to the screening of Sergei Eisenstein’s 1928 cinematic masterpiece, ‘October: Ten Days that Shook the World’ with a live orchestral accompaniment at the Barbican on the 26th October. Tate Modern is still only getting ready to join the wave of exhibitions with its own ‘Red Star Over Russia’ covering artworks from five decades, between 1905 and Stalin’s death in 1953, opening on the 8th November. In the meantime, you can always head to Pushkin House or the Gallery for Russian Art and Design (GRAD) and discover what’s on schedule there.

By Borimir Totev, Executive Editor of SLOVO Journal

Migrants and the Media

By Borimir S Totev, on 13 April 2015

With the persistent misrepresentation of Romanians and Bulgarians in the British press, Rebecca McKeown asks: is it time for an end to unfettered free speech?

Britain’s press freedom must end.

Even as I type the sentence I flinch and want to hammer repentantly on the backspace key. The words read like democracy gone wrong: an attack on a fundamental human right. They bring to mind the heated debates of the post-Charlie Hebdo moral melee. They seem to typify everything that a truly liberal society might hope to denounce.

And yet … I stand by them. The callous portrayal of East European immigrants by the red-top right and the racist generalisations and lies peddled to petulant and ill-informed swathes of the British population have become intolerable. Who gave the British media a free pass to provoke societal division and institutional racism?

Those liberal Britons who have grown up accustomed to the tabloid circus joke at its expense and shake their weary heads at every new, bigoted headline. It seems to me, a newcomer to these green and pleasant lands, that Britain’s populist press is all too often brushed off like an embarrassing drunk uncle—a little bit puckish, a little bit provocative and opinionated, but all in all, harmless.

If you had been a fly on the wall in conversations I have had with UK-based Romanians of late, you would be as certain as I am that such coverage is anything but harmless. Any medium which allows the publication of material that, for example, calls Romanian workers “a huge army of parasites” is in no way innocuous.

It has now been over a year since labour market restrictions were lifted in the UK, allowing Romanians and Bulgarians to work here legally. Certainly, some came. Many went home again too. This is the nature of today’s mobile workforce, and the reality of EU membership. Many Brits count themselves lucky that they can hop across to the continent to live or work in Paris, Munich, Seville, or Budapest. Romanians now have that same right, and, bravo them, many are exercising it.

The great majority of those Romanians who come to the UK prove themselves to be hard-working, honest, contributing members of society, as immigrant communities so often are. But still, still, in this enlightened, largely-liberal, globalised society—still there are a great many Britons who believe the generalisations printed on a daily basis about a people who are no less intelligent, creative, and proud than they are.

Researching this post, I embarked on a Google search for “UK Romanians”. I should not have troubled my fingers with the exercise. So predictable were the headlines, so copy-and-paste clichéd, I could have written them myself given a burst of creative malice. The stories read like bad jokes:

‘Romanian children 130 miles from home demand taxi and McDonald’s at London police station’

And these were only the first three headlines I encountered in a search of the past few days alone. Eighteen months ago, I investigated the media’s depiction of Romanian workers somewhat more extensively. In a study of four tabloids and 315 articles, I categorised each piece by the type of language used and whether a positive or negative depiction of Romanian and Bulgarian migrant workers was given.

The results of the study found that the three right-leaning tabloids (The Sun, the Daily Mail, and the Daily Express) were far more likely to report hyperbolic, negative pieces about Romanians and Bulgarians than the left-leaning Daily Mirror. In other words, the tabloid nature of the paper appeared to have less effect on the anti-Romanian rhetoric published than did its partisan leanings. Some of the headlines recorded during the study included:

‘Bogus Bulgar Benefits Rackets Exposed’

‘Time Bomb: Special Investigation in Romania – Migrants to Bring Drug-Resistant Superbug to UK’

And my personal favourite, demonstrating the innate talent of tabloid journalists at disguising ingrained racism in crude quips: “BULGAR OFF”.

The inanity of tabloid immigration puns aside, the issue of racism towards Romanians (or insert the Central/East European nationality of your choice here) is ongoing and unrelenting. Very often when I meet a Romanian in London, I am shocked by their stories of discrimination. Frequently they are apologetic about their ethnicity. A personal experience of this just two weeks ago almost brought me to tears.

In a small café just north of UCL, a waitress came over to deliver my food. Her accent and appearance led me to believe that she was Romanian, and so I asked her: “Where are you from?”

The look of trepidation and distress that flashed across her face, just for that split second that her eyes met my own, was one of the most heartbreaking experiences of my time in this city. “I’m from Romania”, she replied, every syllable apologetic, bracing herself for what she seemed sure would follow.

My answer, in imperfect Romanian, felt—appallingly—like giving a gift. “Romania!”, I exclaimed, “You have the most beautiful country in the world! I wish I was Romanian!”

How wonderful would it be if such a simple gesture was not so rare as to elicit an overjoyed response? The young woman beamed, sat opposite me for a minute, and poured out her troubles.

“Everyone is horrible to me when they hear I’m Romanian.”

“I miss my family, but this is the best chance I have to support them”

“I want to study, so I am working hard to fund my education”

“The management here treat me very badly. They take the tips I earn and I never see them again”

How I wish this was a one-off conversation. Similar ones are, however, to be had with a great many of the Romanians working hard to earn and contribute here. A young man I met recently came to London to study, but finding himself out of pocket, quit school to work instead. The persistent suggestions that he was in the UK to scrounge off the system had left him determined to prove his worth in a way that other Europeans are rarely forced to:

“I am going to work hard for a few years. Then, when I have enough money, I’m going to walk up to the admissions desk at the university with bundles of cash and pay in advance for my degree, right there on the spot”.

These Romanians, the Romanians that I know and often meet, in no way resemble the violent and dishonest characters that the British press so often choose to splash across their pages and that certain sections of British society choose to see as representative of an entire nationality.

Luckily, I am not the only person who thinks that depictions of Romanians in the UK have spiralled out of control. A group of good people, Brits and Romanians alike, are seeking to remedy the misrepresentations of Romanians in this country. Their documentary is titled 13 Shades of Romanian—but let us not hold this against them. They are producing thirteen stories of thirteen Romanians living in the UK, with the aim of showing a side of Romanians few Brits are exposed to. The project has just achieved its funding goal through a crowdsourced Indiegogo campaign, though they are still welcoming support.

How sad that such a campaign is necessary, and that it is very much an ambulance-at-the-bottom-of-the-cliff remedy. Can Britain’s media not be held more accountable for damning the reputations of every Eastern European who walks through the arrivals gate at Heathrow? As far as I am concerned, the rhetoric that continues to abound about Romanians and other East European expats is a human rights abuse of the first order—more so, I believe, than restricting the unfettered, unfiltered, and unacceptable racism so often printed and consumed in this country.

Rebecca McKeown is a Romaniaphile and Hungarian language learner from New Zealand, currently studying at SSEES. A former radio journalist with interests in diplomacy and development, her current research explores the performance of national cultures in Romania. Twitter: @rebiccamck

Behind Putin’s Self-imposed Food Ban

By Borimir S Totev, on 7 April 2015

By Enrico Cattabiani

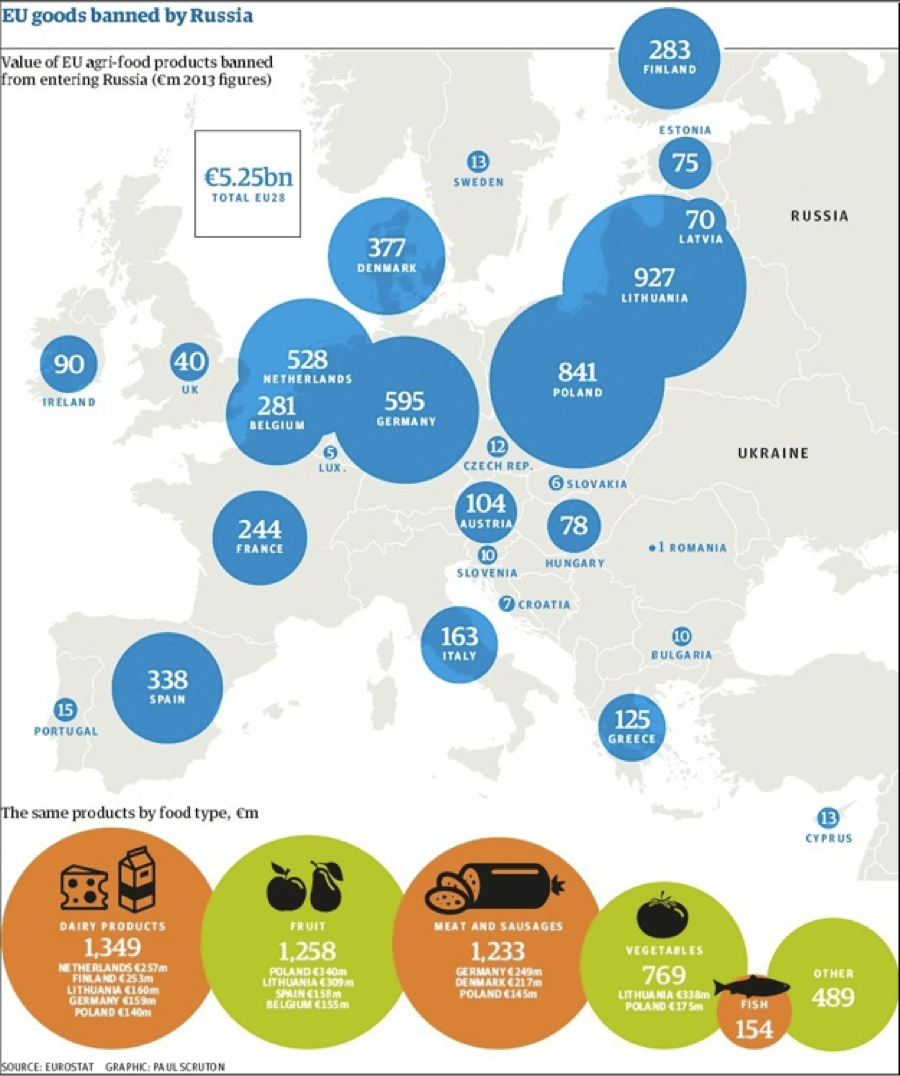

On August 4 last year, Vladimir Putin responded to the latest round of sanctions levied against his regime by imposing a ban on the import of food products from the EU, the US, and their supporters. The disruption of commerce was worth approximately $12 billion to the Russian economy, with secondary effects in the targeted countries, particularly the EU, causing unemployment within the agricultural sector, a slump in the price of the banned foods in domestic markets, and great losses for producers.

At the same time, Russia saw a dramatic rise in food prices, empty shelves in shops, restaurants obliged to change their menus and a revival of the old-fashioned black market, all as a consequence of the ban. Western media has been harshly critical of Putin’s policy, calling it a desperate and useless retaliation done simply for the hell of it. The ban, they argue, is a boomerang that will come back to hit Russia hardest.

There are two very good reasons why this might be true. First, sanctions are a political tool used to force a rival to alter its behavior. In this case, although affected parties in the West are pressing their governments to lift sanctions, damage to the wider European economies has been limited, and the voices of agricultural producers are not strong enough to force a change in policy.

Second, restrictions on trade are usually harmful for any economy, and Russia is no exception. Although it could eventually be beneficial for some sectors, scarcity of products and rising inflation have predictable and undesirable effects on a large segment of the population. Therefore, the ban on food appears to be ineffective in the first instance and counterproductive in the second one.

Why, then, has Putin opted for such an irrational policy? Didn’t he have any alternatives to imposing sanctions – and why food, rather than something else? Before asserting that the ban has been a total failure, however, we must analyze the situation from the Russian president’s perspective.

Why Putin needed to act

Two main political calculations pushed Putin to adopt sanctions. First, to be considered a superpower a country must act like a superpower, and that is certainly the status that Putin seeks for Russia. When the sanctions hit, Russia had to show its muscles and hit back. This is even more the case considering sanctions were imposed in response to Russia’s undeniable involvement in Crimea – which Putin has always denied.

The second reason is purely domestic and concerns the fact that many Russians, thanks to state-led propaganda, perceive the escalation of the Ukraine conflict as the result of Western interference in support of a fascist, anti-Russian coup. Putin’s approval rating rocketed up at the beginning of the turmoil in Crimea, and he has had to keep playing the part of the strongman to maintain credibility at home.

The logic of sanctions: trade-offs, elites, and money

The decision of whether to adopt a particular programme of sanctions is generally made with an eye on the damage, both economic and political, and consequent backlash that they are likely to provoke. In other words, political leaders choose sanctions regimes that maximize damage to its targets and minimize repercussions for their own state or power base.

If we accept that the most important goal of every leader is to remain in power, it follows that, in democratic countries, reducing the impact of sanctions on one’s own economy is essential. Indeed, popular support is necessary to be re-elected, and damaging consumers and businesses for political reasons would likely lead to electoral defeat. This logic has been called the ‘enforcement dilemma’ and expresses the trade-off for the political elite of imposing sanctions.

However, such logic works in a different way in non-democratic countries. Here, to remain in power an authoritarian leader must guarantee a constant flow of money to his inner circle, upon whom he relies for support. In this case, the trade-off is dictated by the need to avoid losses for the elites, disregarding the fallout for the population at large, unless widespread unrest or civil disobedience makes them impossible to ignore.

Such considerations partially explain why Western sanctions have targeted individuals and sectors related to Russian’s elites while Russia has targeted ground-level economic activities in the West.

As such, the repercussions on Western governments of their own sanctions have been manageable, since only a very small fraction of their economies, mostly oil and gas multinationals, have been prevented from trading with Russia. Likewise, Russia’s sanctions haven’t damaged crucial sectors related to the elites’ businesses, nor have they triggered protests or revolts. This may indicate that Putin opted for the solution that caused the least suffering from his own perspective, implying that he acted with absolute (authoritarian) pragmatism.

Behind the choice of banning food

Food is a replaceable good. Russia imports most of it from Western countries. Food is not linked to Putin’s friends’ interests. By bearing in mind these three considerations and by understanding the starting conditions of Russian’s economy, we can put ourselves in Putin’s shoes and understand why he chose to target food imports.

The fall in value of the ruble has led to more expensive imports for Russian firms and to a consequent worsening of the balance of payments. Cutting $12 billion of imports of a replaceable good could help curb Russian dependence on Western countries and slightly alleviate the ruble’s decline. This is not properly orthodox from an economic point of view, for the obvious reasons of rising inflation and widespread shortages, but in Putin’s logic, that $12 billion could also be reinvested and spent elsewhere, which is his declared goal. Where?

The first candidate is obviously the internal market, which can provide goods on the cheap. Second, and more important, are the other BRICS (Brazil, India, China and South Africa) and the countries of Central Asia, with whom a great number of new supply contracts have been signed in recent months. This has contributed to a diversification of Russia’s international trade patterns, which will have further consequences in the long run.

Yet, both the slow pace of transitioning to new suppliers and the inadequacy of local industry in meeting internal demand, as evidenced by the current shortages, demonstrates that not all that money has been spent. Part has been invested in industry, while some may simply have been diverted to other goods.

Losers and winners

Looking at the ban from a broader perspective, consumers, obviously, have been the main losers. Not only do they have access to a much lower quality of food, but they also face the daily uncertainty of sudden price increases. More dramatically, it could also be argued that Putin, conscious of his approval rating and of ordinary Russians’ paranoia about inflation, has played on their fears to trigger a ‘run on food’, letting consumption accelerate in a problematic macroeconomic environment.

This is plainly unsustainable in the long run, but a crucial point, which many critics seem to have forgotten, is that the food ban will – or at least, should – end in August this year. Food prices may gradually return to normal once trade patterns with Western economies are reestablished.

Yet, nothing will be as it was before. Russia’s internal market will have developed, maybe not enough to compete with the EU and the US, but certainly considerably. Many new supply relationships will have been established with countries in the rest of the world. Restaurants may not necessarily revert to their pre-ban menus: people’s tastes are impossible to predict, but who is to say that Russian consumers might not have acquired a taste for cheaper foreign cuisine (Chinese?). All these factors might keep the demand for Western products low.

From a broader geopolitical perspective, Russia’s dependency on Western countries will be further reduced, which is line with Putin’s goals. Moreover, the events in Crimea have accelerated a process that has seen emerging powers try to carve out a bigger role on the international stage by banding together, both in political and economic terms. The disruption of the food trade undoubtedly represents another front in this battle.

August is coming. Conclusions may then be drawn. We will see whether one year of the food ban will have been enough to signal a further step away from Western dependence. More importantly, we will be able to determine whether the suffering of Russia’s population in the short term will result in long-term gains for President Putin. If not, we will be free to criticize his decision to ban Parmesan cheese and other delicacies from Russians’ tables and to reflect on the consequences of a failed policy of economic brinkmanship.

Enrico Cattabiani is on the first year of the IMESS double-degree Masters programme at SSEES, studying Economics and International Relations. From next September, he will study at the Higher School of Economics in Moscow, where he is planning to write a thesis addressing some of the questions left unanswered in this article.

A Hope that Died with Boris Nemtsov

By Borimir S Totev, on 9 March 2015

He understood how Vladimir Putin’s regime worked and still was brave enough to oppose it. He was an outspoken critic of the Kremlin, and never hesitated to make sharp statements against the direction Russia was going. He publicly denounced Russia’s war in Ukraine, and went to the European Parliament to call for the imposition of ‘Magnitsky sanctions’ against regime officials. A former Deputy Prime Minister, who Boris Yeltsin almost named as his successor, a man committed to liberal values, freedom of expression and human rights, Boris Nemtsov has paid the ultimate price for his bravery.

Nemtsov’s murder is the highest profile killing during Putin’s fifteen years of rule. That the leading voice of opposition could be gunned down in public, two hundred metres from the Kremlin, under CCTV cameras that happened not to be working, can hardly be perceived as a coincidence. Like all opposition leaders, Nemtsov was under constant surveillance by the Russian security services. It is hard not to conclude that no matter who pulled the trigger, they were allowed to do so.

During Putin’s rule, several symbolic figures have been sacrificed to intimidate other potential dissidents. In 2003, Mikhail Khodorkovsky, the outspoken owner of the Yukos oil company and the bank Menatep, was arrested and jailed for ten years. His imprisonment brought the oligarchic class to heel and consolidated Putin’s ‘vertical’ of power. In 2006, Anna Politkovskaya, a prominent reporter of the Russian Army’s abuses in Chechnya, was shot dead, apparently as a warning to other journalists.

One month later, Alexander Litvinenko’s death proved that no one is beyond the reach of the regime. The former FSB officer, who became an outspoken critic of Putin, was poisoned by radioactive polonium in London. In 2009, Sergei Magnitsky, a lawyer who accused Russian officials of large-scale theft and tax fraud, died in prison after being denied medical care. Thus the most vocal critics of the Kremlin have often ended up silenced.

Semi-official theories about Nemtsov’s murder have pinned the blame on everyone from Islamist militants, to Ukrainians, to CIA agents, to liberal provocateurs, to Nemtsov’s lover, the 23-year old Ukrainian model Anna Duritskaya. Vladimir Putin’s spokesman, Dimitry Peskov, implied that the state had no reason to want Nemtsov dead when he commented that “Boris Nemtsov was only slightly more than an average citizen”.

It is true that Nemtsov was not immensely popular as a politician. His role in Yeltsin’s governments in the 1990s led many Russians to regard him unfavourably. He lost his seat in the Duma in 2003, and came a distant second in the Sochi mayoral elections in 2009. He certainly did not have the profile of the anti-corruption activist Alexey Navalny, released from jail last Friday after serving a fifteen-day sentence for distributing leaflets.

However, with the rouble crisis, a shrinking economy, oil prices down 50% and rising unemployment, a leader like Nemtsov could have become a real threat for Putin’s regime. He had been a longstanding irritant for the Kremlin, producing reports for several years detailing government corruption and incompetence, but it was the Ukrainian crisis that returned him to national prominence.

A supporter of the Orange Revolution in 2004 and a former adviser to president Viktor Yushchenko, Nemtsov had been among the first to criticise Putin’s annexation of the Crimea. Last year he produced two films which highlighted Russia’s military involvement in Ukraine and suggested Russian rebels may have been responsible for downing Malaysian Airlines flight MH17.

At the time of his death, he was preparing to publish a report based on interviews with relatives of Russian soldiers who had been killed fighting in Ukraine, which would have further undermined Putin’s assertions that no army units were on Ukrainian soil. Not for nothing did Ukrainian president Petro Poroshenko describe him as “the bridge between Ukraine and Russia”.

Just weeks ago, Nemtsov said in an interview: “I am afraid Putin will kill me”. Even though he knew he was in danger, he continued to condemn the Russian president’s aggressive domestic and foreign policies, and the principle of ‘managed democracy’ by which the state exercises control over television channels and the press. It is Putin’s media that is behind the intolerant and paranoid public mood in Russia today, which portrays opposition leaders as evil forces, foreign agents and traitors. The responsibility for the atmosphere of murderous hatred in which Boris Nemtsov was killed lies squarely with Vladimir Putin.

Five men are now in police custody, suspected of Nemtsov’s murder. But this will not bring about an end to speculation over who pulled the trigger, and who gave the order. Few of his supporters expect the full truth to come to light. With Boris Nemtsov died another piece of hope that Russia might become a liberal country without totalitarian features, a democratic country without adjectives, and a place where individuals will be able to express their thoughts without being afraid that they will be the next victims of the regime.

Natia Seskuria is completing her Master’s degree in Politics, Security and Integration at SSEES. Her thesis focuses on the Russian-Georgian War of 2008. Follow her on Twitter @natia_seskuria.

Destination in Doubt: Ukrainian Football in Time of Conflict

By Borimir S Totev, on 1 March 2015

Manuel Veth

The veto was immediate: European football’s governing body UEFA will not allow Dinamo Kiev to wear the slogan ‘Geroiam Slava’ (Glory to Our Heroes) in place of their usual sponsor’s logo for matches in the Europa League. UEFA, they explained, does not allow political slogans of any kind in its competitions. Dinamo’s gesture was intended to commemorate the victims of the Maidan protests, and the Ukrainian soldiers who have died fighting in the Donbass. They also wanted to return international attention to Russia’s involvement in the conflict. But despite UEFA’s attempts to keep the game apolitical, football and politics are deeply intertwined in the events that have taken place in Ukraine since Euromaidan in the winter of 2013/14.

This connection predates the revolution. Oligarchs, who own the majority of the clubs, have used football in connection with large media empires in order to create strong political profiles, a process that was copied from the former Italian Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi, and has fittingly been termed the Berlusconization of Ukrainian football.

Ultras: from protesters to soldiers

While the clubs, and their ownership structures, represent the upper echelons of Ukrainian society, fans have also had a major impact on recent political events in Ukraine. Organized fan groups called ultras were influential in the events that took place on the Maidan in Kiev. Ultras from across all major clubs formed defence units to protect protestors from thugs hired by President Viktor Yanukovych, and were therefore instrumental in removing Yanukovych and his cronies from government. In addition, as the Twitter account by the Ukrainian blogger Oleksandr Sereda indicates, many of the ultra groups have now taken an active role in the conflict that is taking place in the Donbass by forming irregular units to fight the Russian-backed separatists.

The Ukrainian ultras are not alone in their fight. Across the Black Sea, in Georgia, Torpedo Kutaisi fans held up a banner last weekend to honour the deaths of Georgian irregulars who have fought and died in the Donbass. A war for Ukraine’s independence, in the eyes of Torpedo fans, is also as a war for Georgia’s independence.

This all serves to underline the complexity of the military situation in the Donbass. While Russian mercenaries, and regular military units, are supporting the rebels, the Ukrainian army has itself made use of foreign mercenaries and irregular units. While the separatists have rightly been accused of ceasefire violations, the composition of the government’s forces makes it difficult for Petro Poroshenko’s administration to guarantee the ceasefire on their own side. Any peace process could indeed be complicated, as it will not be easy to force the various groups involved on both sides, many of which have become extremely radicalized since the conflict began, to lay down their weapons.

Ukrainian Premier League: the show must go on?

Despite the continued fighting in the Donbass, football is supposed to return for the second half of the Ukrainian Premier League. While it is hard to imagine how sport can continue in a war-stricken country, officials have argued that only a small part of the country is truly affected by the fighting. At the same time, however, Donbass is home to five of the 14 clubs in the Ukrainian Premier League. These clubs—Shakhtar Donetsk, Olimpik Donetsk, Metalurh Donetsk, Zorya Luhansk, and Illichevets Mariupol—have now been forced to play their games in exile.

A sixth club, Stal Alchevsk, has also been badly affected by the fighting. Alchevsk is one of many bleak mining towns located in the Donbass, and the club’s name Stal (Steel) reveals the close connection between the club and its sponsor, the Alchevsk steel and iron works. Due to the fighting, Stal Alchevsk has been playing in exile in the Poltava region, yet the club has maintained its training base in Alchevsk under unstable conditions. As head coach Anatoliy Volobuyev explained: “Alchevsk is only 40 kilometers from Debaltsevo and we can hear the fighting from here. Recently, we’ve had a rocket hit the town too. To play football in these conditions simply isn’t right.”

Under these difficult financial and psychological circumstances, the club has now decided to withdraw from the Ukrainian Pervaia Liga (second division), as the Alchevsk steel works has been taken offline due to the war. Arsenal Kiev stand ready to purchase Stal Alchevsk’s licence, and with it their place in the league, which may effectively mean Stal Alchevsk ceases to exist as a club. The episode has brought renewed uncertainty to the future of Ukrainian football, as more clubs from the region may be forced to discontinue their participation in professional football.

The Ukrainian Premier League had struggled to field a full list of teams even prior to this troubled season, and as a result the league had been downsized from 16 to 14 teams. Last week legendary ex-striker Andriy Shevchenko appealed to the authorities not to suspend the league altogether. But the very fact that he had to speak out suggests that this option is now very much on the table.

Shakhtar Donetsk: the fall of a giant?

While the future of the Ukrainian Premier Liga remains in question, Ukraine’s most successful team in recent years, Shakhtar Donetsk, is preparing to play Germany’s biggest club, Bayern Munich, for a place in the UEFA Champions League quarter-finals. The first leg on February 17 was held over a thousand kilometres from Shakhtar’s home, in Lviv (closer to Munich than to Donetsk). Against expectations, Shakhtar held Bayern to a 0-0 draw, giving themselves a fighting chance of progressing to the next round. But the second leg in Munich is still to come, and Bayern, having won thirteen and drawn one of their fourteen home fixtures so far this season, are overwhelming favourites.

Defeat would be another major blow for Shakhtar’s owner Rinat Akhmetov. Before the conflict in the Donbass, Akhmetov was the richest man in the former Soviet Union. Often considered the pivot of the so-called ‘Donetsk clan’, a loose political alliance of Donbass oligarchs, Akhmetov was also regarded as the financial backbone of the Partiia Regionov, the political party of former president Viktor Yanukovych.

The events at Euromaidan and the war, however, would mean that a tie against the Germans could be the last match for a while on the international stage for both Shakhtar and Akhmetov. Being based in Lviv has taken a toll on the team’s performances. Shakhtar are currently second in the table, five points behind their arch-rival Dinamo Kiev and only three points ahead of Dnipro Dnipropetrovsk. With only the top two teams qualifying for Champions League football, Shakhtar’s participation in next year’s competition is very much in doubt.

It is not only in football that Akhmetov is feeling the pressure. The conflict in the Donbass has seen many of his assets destroyed in the fighting. He is also facing an investigation over his alleged financing of separatist forces. There is political pressure too: Ihor Kolomoyskyi, another oligarch long regarded as a counterweight to Akhmetov, has emerged as one of Ukraine’s most powerful men and now seems able to dictate the country’s political and economic direction. Kolomoyskyi is the owner of Dnipro and, since March 2014, governor of the Dnipropetrovsk oblast. He has also announced his intention to run for the presidency of the Football Federation of Ukraine (FFU), replacing Anatoliy Konkov, widely seen as Akhmetov’s man. The reshuffling at the top of the FFU reflects the political reorganizations elsewhere in the country.

Conjoined twins: football and politics in Ukraine

With all these examples in mind, it is hard to believe that UEFA’s attempt to keep football apolitical will truly amount to much. While political slogans should indeed have no place in football, realistically fans and clubs have always found ways to introduce them into the game. Dinamo Kiev have already announced plans to wear their ‘Geroiam Slava’ shirts for matches in the Ukrainian Premier Liga. With fans fighting in the Donbass, clubs being forced into exile due to the conflict, and oligarchs using football as a vehicle to assert political control, football and politics in Ukraine, as elsewhere in the post-Soviet space, have long been conjoined twins.

Manuel Veth is a final-year PhD candidate at King’s College London. His thesis is titled: “Selling the People’s Game: Football’s transition from Communism to Capitalism in the Soviet Union and its Successor States”. Follow his research and writing at Futbolgrad.com.

The Creep of Nationalism in the First Russian State

By , on 30 January 2015

On December 15 last year, a blog appeared in Russia claiming that the Belarusian regime is comatose and sleepwalking to a revolution as it allows the West to undermine it. It was followed five days later by a short documentary film, Military Secrets, which furthered the claim that Belarusians in western Belarus were in the pay of Europe. Both spelled out Russian displeasure with Alyaksandr Lukashenka’s regime and spoke of the need for Russia to counteract this threat either by replacing Lukashenka with a more pliant pro-Russian leader, or by increasing the Russian presence in Belarus.

Why would a pro-Kremlin blogger, albeit a relatively minor one, and a TV channel have reverted to castigating Lukashenka? Not since the 2010 film The Godfather has Lukashenka faced such Russian ire. This is partly due to Minsk’s unwillingness to rally behind the Kremlin and give support to the escapade in Ukraine and partially because the Belarusian regime appears to be finding some long-forgotten Belarusian identity.

The rise of Belarusian identity?

Belarus has been alarmed by Russia’s adventure in Ukraine, especially its annexation of Crimea under the guise of protecting ethnic Russians. Having experimented at length with different ideologies, Lukashenka has had to reverse years of telling Belarusians they are the first Russian nation. After all, if Belarusians are Russian, as Lukashenka has claimed, then it makes it easier for Russian nationalists to claim that Belarus does not exist.

One such group marched through the Belarusian city of Vitsebsk in early November, calling for the reuniting of all Russian lands. At the same time, other Russian nationalist groups like the Orthodox Brotherhood and the wonderfully-titled Russian Public Movement for the Spiritual Development of the People for the State and Spiritual Revival of Holy Rus’ have become active in Belarus.

There has been political friction too. In November, Russia banned Belarusian meat and dairy products, to chastise Lukashenka for his support of Ukraine and for attempting to undermine Russian sanctions on EU food. The loss of $160 million in five days drastically affected the Belarusian economy and emphasised to Minsk that overreliance on Russia was dangerous. At the same time, events in Ukraine and the impressive mobilisation of Belarusian youth into Russian organisations have alarmed the authorities to such an extent that Minsk is now promoting a distinct Belarusian culture.

Lukashenka would not call this nationalism, which he recently and publicly condemned. However, like so much else in the Shangri-La that is Belarus, rhetoric and reality do not match. Nationalism is a dirty word after the failure of the Belarusian National Front (BNF) in the 1990s. Instead, what is occurring is a conscious promotion of Belarusian culture without explicitly nationalist rhetoric, and a concomitant marginalisation of Russia and Russianness.

As early as November 2013, Lukashenka had begun to look past Russia to the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, to offer Belarus a different national-historical narrative. This culminated in the unveiling of a monument to a Lithuanian Grand Duke in July 2014, which Russia had long opposed. Then, in December, Lukashenka moved his ‘grey cardinal’, Andrei Kabyakou, to the position of Prime Minister. Despite his Russian origins, the Kremlin appears to consider Kabyakou less accommodating then his predecessor Mikhail Mayasnikovich.

The Belarusian government has also debated increasing the number of hours of Belarusian language training at schools, at the expense of Russian and English. The language issue is particularly stark, given that Vladimir Putin justified intervention in Ukraine by citing the need to protect ethnic Russians, which for him meant Russian speakers. In a country like Belarus where nearly 95% of the population speaks Russian, and most use it as their first, or only language, this is a worrying turn of events.

Pidgin nationalism

This beginning of the creation of a Belarusian identity is so far limited. It also smacks of something else. Lukashenka has been adept at creating ideologies for himself that are empty caskets to which he adds different items depending on his needs. He began with visions of neo-Sovietism and of Belarus as a part of an Eastern Eurasian civilisation, remarking that “Belarusians are just Russians but with the sign of quality”.

This concept of Belarus as a part of a Russian world evolved into a claim that Belarus was on a higher level of civilisation than Moscow and represented the fourth Rome. This in turn evolved into the ‘For Belarus’ ideology, the emptiest casket of all, into which Lukashenka poured a mixture of state centralism and nationalism-lite. It is highly probable that we are now coming full circle as Lukashenka reverts to promoting to a domestic and international audience the concept that Belarus is different from Russia.

It is a cynical and pessimistic view, but Lukashenka has promoted such a notion before when he felt that he could make political capital from it. Since 2013, Belarus’s foreign minister Uladimir Makei has practically been living in Europe, flying between Brussels, Warsaw and Belgrade. Indeed, his deputy Alena Kupchyna appeared to have set up a permanent residency in Brussels for a long time to try and improve the relationship between Belarus and the EU.

Belarus’s relationship with Lithuania has warmed, and the ‘teddy bear incident’ of 2012, when a private Swedish plane dropped soft toys carrying anti-regime messages over the country, was relegated to history as Belarusian envoys even went to Stockholm. The Ukraine crisis has provided Lukashenka with the perfect opportunity to show that he is not the worst bastard in the former Soviet Union. As Russia becomes pariah number one, it is highly likely that Lukashenka is trying to placate European states and distance himself from the erstwhile motherland.

The juggling exhibition continues

The analogy of Lukashenka as a juggler remains apt. He is brilliant at playing off Russia and Europe while doing just enough to keep the stuttering Belarusian economy afloat, to keep ordinary Belarusians relatively appeased, and to maintain his grip on power. With a presidential election coming up this year, he may have guessed that simply by not being cosy with Putin, Europe will turn a blind eye to his electoral fraud and quashing of protest. The release of political activist Ales Byalyatski may have been the first step in this strategy.

It has been suggested that Lukashenka wants to push Russia into backing him more closely for fear that he may slip Moscow’s leash for good. However, I do not buy this idea. Belarus is now nearly totally reliant on Russia not only for oil and gas, but also as an export market, and the a Belarus entirely detached from Russia’s orbit does not seem a realistic prospect inside the Kremlin or anywhere else. Belarus may well look to diversify, but for a state that has been a part of all Russian regional institutions, isolationism looks an idle threat.

Maybe, just maybe, the clown is becoming a nationalist

Gauging the juggler is a difficult task, but I think that the Ukraine conflict has spooked the Lukashenka regime. If you are not with Putin, you are against him, according to Gleb Pavlovsky, one of the former ‘grey cardinals’ of the Kremlin, and the Russian president will not forgive Lukashenka for siding with Ukraine. With the continuing squeeze on the Russian economy under Western sanctions and the falling price of oil and gas, it is possible that an isolated country, considered by many Russians to be six western oblasts of Russia, will become too much of an attractive target, as the Kremlin looks to bolster its public support.

Whether Lukashenka’s newfound (or rather re-established) nationalism remains a pidgin or limited nationalism remains to be seen. I feel that this current incarnation of ‘nationalist Lukashenka’ may actually be relatively real. He has been very protective over his personal fief and has been loath to cede power to Russia before. He has often enticed Russia to support him with promises of privatisation only to renege on the behind-doors deals. Now fearing the hand that feeds him he is likely to protect his cave from this more dangerous friend.

This does not mean however that Minsk will look west. Lukashenka has tried this before, and every time European governments have spoken of human rights he has gone back to Russia. Besides, the Kremlin would not accept a Western-oriented Belarusian regime. Moscow knows that Belarus is beholden to it and will eventually return to its embrace. But, for the first time, it must confront a more assertive Belarus determined to create its own identity.

Having spent the early part of his tenure eradicating any nationalism that was not controlled, Lukashenka has ample avenues to build a Belarusian nationalism he can control. Talk of him undermining his own regime is overblown, as the juggler is adept at maintaining support from diverse societal factions. The clown may, just may, have clothed himself in nationalist garb. It is not yet clear whether these vestments are more than just for show, to be changed when needed, or whether a more nationalist Belarus is here to stay. Without political competitors and fearful of a resurgent Russia, Lukashenka the clown may just become a Belarusian nationalist.

Democracy in Poland has a Masculine Gender? Gender and Catholicism in Polish Identity Today

By Slovo, on 1 August 2014

Hannah Phillips explores the toxic interplay between Gender and Catholicism in Poland today

‘In times of oppression the struggle for independence is considered a serious matter, and the fight for women’s rights is not… It took some time before I realized that democracy in Poland has a masculine gender’

Marion Janion (Conference of Polish Women, 2009)

As though to prove the relevancy of Janion’s pessimistic view of contemporary Poland, an emotionally charged and intoxicating debate has been unfolding in the Polish media. Similar to the 1990s popular, anti-feminist backlash in the West (mainly the USA and Britain), two ontologically opposing camps are at loggerheads in Poland: the conservative right alongside the Church versus the feminists. With fear-mongering banners and statements such as ‘Gender=666’ and ‘Gender- the devastation of man and the family’ strung across buildings and scattering the news, it is clear that a war has been declared against “Gender ideology”.

Like most meaningful political and social concepts, Gender theory has been notoriously difficult to define and is largely in the process of transformation and revision. Having been sculpted by post-structuralist thought, it has criticised putative concepts we deem rigid and “natural”, such as sexual identity, illustrating the oppressive capabilities of socially constructed “norms”. The rather abstract nature of Gender construction has led, unfortunately, to an easy manipulation of meaning by Catholic conservatives and right-wing politicians in Poland. In the 29December 2013 annual ‘Feast of the Holy Family’ for Roman Catholics, the Polish Episcopate publically declared in its Pastoral letter that Gender was the official enemy of the Church. The Episcopate paints a conspiratorial picture of a parasitic ideology that infiltrates various social structures, such as education and health systems, without the consent or knowledge of Poles. Perceived as an accumulation of foreign concepts, including radical feminism, Communism and eugenics, Gender is seen as destroying Polish families and over-sexualising children. The final version of the letter, currently available online, is milder than the original, previously entitled ‘Gender ideology risks the family’. It was revised aftera moderate Catholic weekly, Tygodnik Powszechny, published the draft showing the original inflammatory edits.

The more extreme and exotic claims from the Polish Catholic church entail the vilification of various international institutions, blamed for leading the Gender conspiracy. There is a widely held belief that the Council of Europe’s ‘Convention on preventing and combating violence against women and domestic violence’ is the vehicle through which Gender ideology penetrates the Polish society. According to the Episcopate this Convention is allegedly breaking down the education system in Poland in order to force homosexuality and transgender education on children. More audacious claims insist that the WHO is even promoting masturbation in Primary schools. This was further echoed in a lecture held in the Sejm earlier this year by the theology Professor and Priest Dariusz Oko, ubiquitously present in the media for his extreme, anti-Gender views.

These views are not however uniquely held and promulgated within religious circles. In the political sphere, Conservative politicians have also voiced their contestation, forming a new parliamentary group in January this year named ‘Stop Gender Ideology’. Open to any MP regardless of political party affiliations, the aim of this group is to defend human sexual identity and work towards legislative changes to defend the rights of traditional families and support family-friendly policies. Beata Kempa, in the past a member of the right-wing Law and Justice Party before forming a new right-wing party United Poland, is a current President of an almost entirely male-membered group, with plans to promote the anti-Gender campaign during sixteen conferences across Poland this year.

As stated by Małgorzata Fuszara, a sociologist and head of Gender Studies at Warsaw University, there is a deliberate intellectual laziness in comprehending Gender to further the Church’s self-interests. Luckily, in the majority of reputable Polish media outlets the weaknesses in the Church’s arguments have been ardently pointed out. Polish Feminists, university Professors, philosophers and politicians have strongly opposed the Church’s conflation of the ills of society into this fictive “Gender ideology”. Magdalena Środa, a philosophy Professor, feminist and columnist for Gazeta Wyborcza, has vehemently discredited the Church, outlining how it is using scare tactic propaganda against Gender as a distraction from the contentious issue of paedophilia. By alluding to foreign supranational entities, for instance, the responsibility for “society’s evils” is by virtue of exogenous factors out of the Church’s control. It is no coincidence that the anti-Gender debate comes at a time of moral crisis for the Church as scandals of child molestation and ill-treatment of children by religious officials effectively dent its former image as the nation’s moral compass.

It is important, however, to highlight that this debate is not unique to Poland, or Eastern Europe, for that matter; a similar debate led by religious and political right groups is also currently unfolding in France. Alongside the current economic crisis and uncertainty regarding the future developments of the European Union, there is a pull amongst populations towards a form of stability. For many this means reinforcing the historically cemented roles of the family and the reassuringly fixed structures provided by Catholicism. The debate in Poland is thus illustrative of the stronghold of staunch Catholic religiosity playing a crucial role in the self-identification of Poles. For many Polish feminists it is also a reminder that Poland’s democracy is still male and proudly sporting a clergyman attire.

Close

Close