The Innocence and Violence of EuroMaidan: Notes from Kyiv

By Slovo, on 31 January 2014

SLOVO Journal’s editor Ed Johnson visits Kyiv to see beyond the media bias and discover EuroMaidan for himself

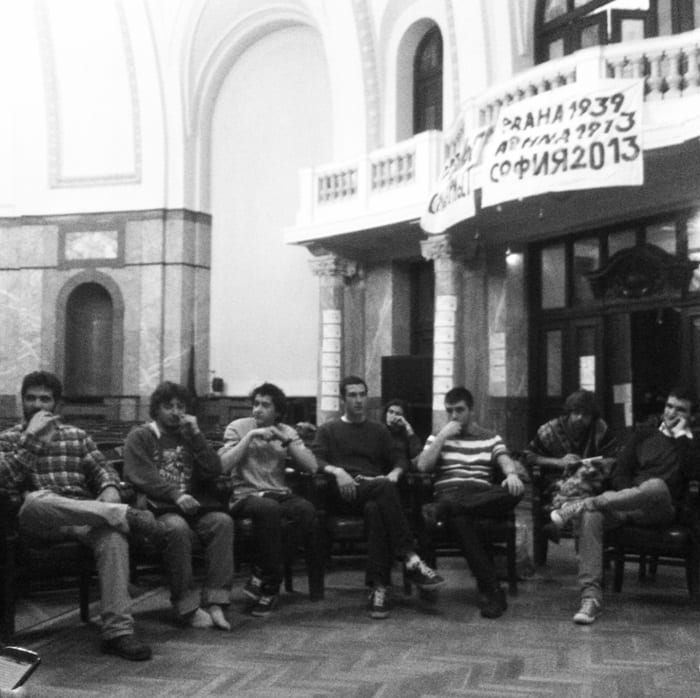

The Maidan was packed with people, tents, and flags. The national anthem rang in my ears. The mood was electric and tense. It was Euro 2012—the last time I was in Kyiv—when, for a month and a half, the city was consumed with football, summer, and celebration. I found myself reflecting on the times I spend on Maidan that summer, whiling away the hours watching football on the giant screens erected on Khreschatyk. As I entered the barricades of EuroMaidan the expanse of the protest village became evident. Nestled below a thick layer of wood smoke belched into the air by hundreds of tents and braziers, humming with the sound of bustling demonstrators, it appeared mythical.

Having only read about the protests from afar, I had developed an image of Maidan, but nothing prepared me for the reality of it. My first trip to the EuroMaidan was a blur: my mind lost in the hive of activity, acrid pine smoke, clanking metal, and the drone of the loudspeakers. Entering the square, we passed through security, organised and run by the protestors. Each guard had “official” Maidan Security accreditation, complete with an individual I.D. number. The guards check mainly for drunks or provocateurs, but give the impression of entering an autonomous zone with anti-government and Yanukovych graffiti adorning the entrance. The place was alive with people at nine o’clock on a Thursday evening. Everywhere I looked someone was doing something: serving tea, chopping wood, clearing snow or filling bags for the barricades. The streets of the Maidan, devoid of snow and cleaner than many of those in the rest of the city, led us into the maze of tents. Piping hot ‘euro-borsch’ was being dished out of steaming pots to frigid protestors while volunteers presented trays of donated sandwiches. The sense of self-sufficiency was striking, exuding an air of an unshakeable community set on achieving its goals. Clearly such a romanticised view ignores the very real political machine behind the demonstrations.

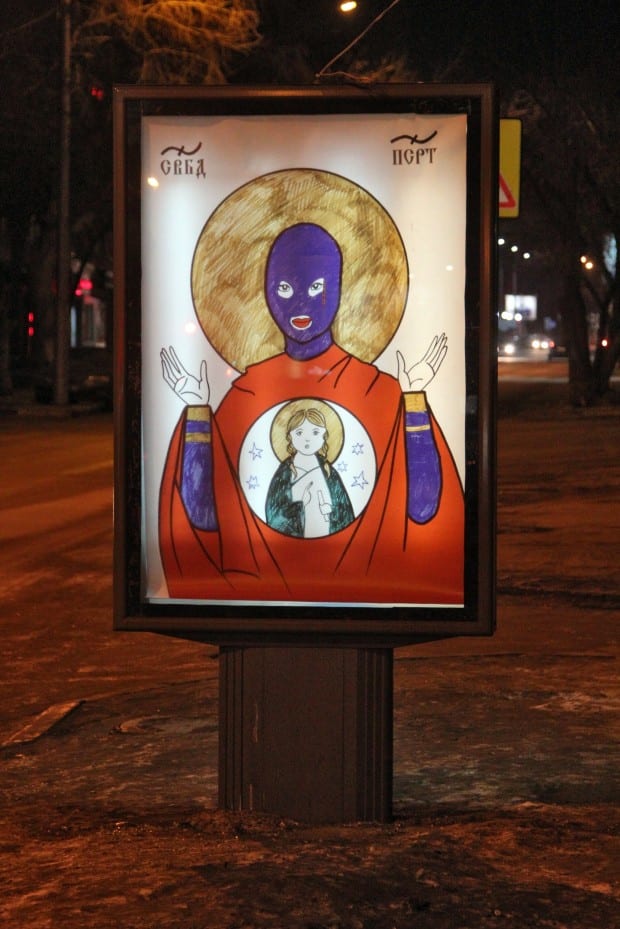

From the calm of the Maidan we walked east, down to the bottom of Hrushevskoho Street, the flashpoint for violence between police and protestors. My friend who had witnessed the violence earlier in the week was reticent about returning. However, the situation was calmer than the previous days. The air was still clogged with the smell of burnt rubber, but the wall of flames of Wednesday had subsided, and, in its place, a new barricade was constructed, complete with ramparts. Protestors stood atop this wall of snow, metal, and second hand tires, surveying a scene of burnt out buses frozen into place by water cannons and further onto the stationary, homogenous mass of the police lines. Certainly the atmosphere here was different to that within the confines of the Maidan itself. Men wrapped in foam cladding practised fighting with wooden sticks. A man with a microphone and an enormous flag led the crowd in chants of ‘glory to Ukraine’, eliciting the deep roar of ‘glory to the heroes’. On this street, two demonstrators were shot dead only days before. The man screamed on, ‘glory to the nation,’ ‘death to the enemies’, ‘Ukraine above all’. These controversial chants, strongly associated with Ukraine’s fascist wartime movement give light to the fact that right wing groups, anathema to the European values they are fighting for, are represented amongst the crowd. The extent to which the protests have been co-opted by these extremist groups is a challenging topic. Certainly these protests are national in nature, in the face of domestic and international challenges to a Ukrainian nation. The difficulty I found was to reconcile the presence of violent nationalists alongside the majority of peaceful, pro-European, anti-Yanukovych protestors. Reports in the media paint juxtaposing pictures: on the one hand, peaceful civil protests, where young and old alike come together against oppression and unite behind a European ideal. On the other, the new narrative of the violent conflict driven by roving gangs of extremist right wing thugs and provocateurs.

As I wandered the Maidan I struggled to process it as a whole. It became clear to me as I walked through the protests and then out of the centre of Kyiv, into the frozen side streets and eerie calm of the rest of the city that the Maidan is not one thing. The movement is fluid and frustratingly difficult to characterize in the context of such a volatile political situation. Civic leaders from the leader of the Crimean tartars to the Orthodox church choir appear on stage only meters away from a prominent portrait of Stepan Bandera, the symbolic leader of Ukraine’s violent wartime nationalist movement. The contradictions are evident within EuroMaidan, it is not exclusively peaceful; it is not totally violent. Maidan is not innocent nor is it an unacceptable expression of 20th century fascism.

The ‘front-lines’ of Hrushevskoho Street exudes the juvenile machismo of young men dressed up in the uniform of war, wielding sticks. Yet many protestors are deeply professional, effective and sincere in their conflict with the police. I witnessed the absurd side of this when late on Friday night in -18 C weather, amidst exploding fireworks and the furnace of burning tires, a protestor on the frontlines stood astride on a burnt out bus, took off his coat and shirt, turned to the crowd, and held a revving chain saw aloft, knowing full well that the billowing smoke behind him illuminated his stance to the lenses of the photographers below. This seems absurd, overly violent and representative of the juvenile element. As I turned to leave the barricades, my perceptions were again challenged. In a bid to disperse the water from the police cannons protestors were carving channels through the ice, forcing the torrent down the street. Further down countless protestors where arranging bags of ice to direct the flow into a drain and prevent the barricades turning into an ice rink.

Nationalists, pro-Europeans, violent thugs, frustrated revolutionaries, and numerous other sub-categories and groups mean that these protests are too diverse to be simply described as one or the other. They have emerged together as part of a large social movement, which, whilst empowering and impressive in many aspects, has darker aspects. I saw symbols of the far-right and, as my stay went on, increasing numbers of paramilitary training exercises. This worrying trend threatens to overshadow the side of the protests which has some people, who previously were indifferent about politics in Ukraine motivated to camp out on a freezing square and participate in a grass-roots protest against their government.

I went to Ukraine to learn more about EuroMaidan as much as to experience this moment in Ukraine’s history. I returned with a better understanding of the make-up of the coalition of protestors but also a strong sense of the anger and disillusionment of the demonstrators. I wanted to see what EuroMaidan had become two months on from the original occupation of the square. In contrast to the euphoria of Euro 2012 I witnessed a deep disillusionment and anger amongst people who had hoped that tournament to become the beginning of Ukraine’s European journey. The EuroMaidan is an impressive feat, yet poses as many questions as it does solutions. Certainly Ukraine’s European journey hinges on its success.

Close

Close