History of a Nation: Ukrainians Under the Second Polish Republic

By Slovo, on 3 March 2014

The perturbations in Ukraine we see these past months are just an episode in its long history of finding its place in the region’s geopolitics, of fighting to be heard amidst the overwhelming national politics of its neighbors. Hannah Phillips looks at another historical juncture in Ukrainian history – Ukrainian minority under Poles in interwar Europe.

Many Western observers have framed the ongoing protests in Kiev as a desperate call of the Ukrainian people to their government to focus its efforts on working towards membership in the European Union. While this narrative has been criticised by scholars for its attempt to oversimplify the motivations of the numerous groups constituting the ‘Euromaidan’, a desire to belong to a broader European community has undoubtedly been frequently voiced by Ukrainian opposition leaders.

Throughout history Ukrainians have been forced to live in less benign types of supranational formations than the EU. Tsarist Russia, the Austro-Hungarian Empire and the Soviet Union all had a colossal impact on the shape and identity of the Ukrainian nation. In this article we would like to take a brief glimpse at another ‘forced union’ in which a large portion of the Ukrainian people lived for over two decades of the 20th century – the Second Polish Republic.

Poland regained its independence in 1918 after 123 years of being torn between three multi-national empires. Every aspect of unification presented a daunting task in the construction of a coherent state. Alongside such obstacles lay the question of nationhood.

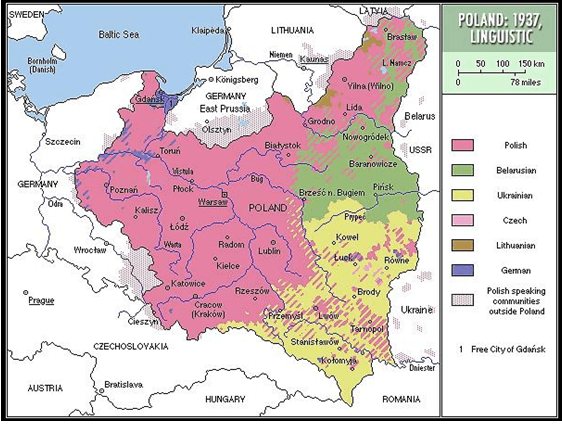

During the Paris Peace Conference, newly drawn frontiers across Europe placed many inhabitants at odds with the majority population in race, language and religion, creating ‘minorities’. The Second Polish Republic was no exception. The 1921 National Census data revealed that minorities constituted approximately a third of all citizens; Ukrainians were the largest minority, making up 14.3%. The Ukrainian population mostly dominated one area of Poland, namely the Kresy (Eastern borderlands), which today lie outside of the Polish border, mostly within the modern states of Ukraine and Belarus. Taking language usage as an indicator for population distribution, the following map provides a visual overview of minority-concentrated areas in Poland in 1937. ‘Minority’ Ukrainians often constituted actual majorities in provinces such as Stanislawow (69.8% in 1928) and Volhynia (68.4%).

The long history of coexistence of Poles and Ukrainians was punctuated by episodes of violence and conflict. The most famous of these was the bloody Khmelnytsky Uprising of 1648, during which Orthodox Ukrainian Cossacks rebelled against Polish Catholic magnates. The disputes persisted throughout the next centuries, with ownership of land a particular bone of contention. At the beginning the 20th century, under the Habsburg monarchy, about 4,000 Polish families owned as much lands as three million former Ukrainian serfs. Territorial claims thus inevitably fed into the bitter relations between Poles and Ukrainians in the interwar period.

After the First World War, Polish independence enflamed Polish-Ukrainian tensions centering on Eastern Galician territory. The 1918 Ukrainian coup in Lwów set a precedent for future clashes, especially when the Treaty of Riga ceded Galicia to Poland. Eastern Galicia became a hotbed of discontent as Polish authorities dismantled institutions, dismissed Ukrainian officials from the civil service and renamed the province to Małopolska Wschodnia (Eastern Little Poland). Furthermore, Ukrainians were in the majority in Eastern Galicia, and had developed a national consciousness, driven under Habsburg rule by a small but robust intelligentsia.

The Polish government did not, however, entirely oust its Ukrainian minority. Poland signed the Minority Treaty, albeit begrudgingly, guaranteeing certain civil, judicial and political rights to the Ukrainian minority. Concessions were initially granted so Ukrainians were able to manage their own religion, press and political parties. Ukrainian deputies and senators sat in the Parliament and a daily Ukrainian-language newspaper, the Dilo, was published.

Yet this did not settle Ukrainian nationalist resentment towards Poland. Polish coalition governments increasingly disputed the provisions of the Minority Treaty, and led a polonization of Ukrainian schools and local governments. In response, Ukrainians became increasingly militarised, creating groups like the Ukrainian Military Organisation (UVO) which instigated terrorist activities such as the 1921 attempted assassination of Józef Piłsudski, Poland’s Chief of State. Furthermore, attempts by Ukrainian parliamentarians to collaborate with the Polish state were undermined by underground nationalist movements. In the 1930s these movements launched a widespread terrorist campaign where terrorist acts, such as arson and disruption of transport, intensified precipitating the brutal “pacification” operation led by Piłsudski. Social stability was, therefore, inhibited by the self-propagating nationalist discourse between nations and the state. Polish-Ukrainian relations remained tense throughout the interwar period.

As outlined by Ernest Gellner, the concept of the nation serves to culturally homogenise a population and legitimise a state’s ability to govern. This need for unity comes to the fore in times of crisis, such as after a war. Poland’s patchwork of converging nationalities, made nation-building a political problem reflected in dealings with the Ukrainians. The lack of any real integration policy made this a permanent issue throughout the interwar period. Polonization, internal armed conflict, and populating Ukrainian lands with Polish settlers deepened the divide. This prompted a growth in minority support for nationalist groups opposed to the exclusionary Polish state. This in turn fed into further minority persecution from fear of a foreign threat to Polish independence. The minority problem was thus not ever resolved but merely perpetuated.

Poland was not alone in confronting ethnic clashes. Most Eastern European states were dealing with a highly nationalist discourse of interwar Europe, afflicted by economic downturn and social demoralization. The idea of a homogenised nation along racial lines became the focus for consolidating an independent Poland, and xenophobia thrived. One cannot, however, entirely blame Poland for failing to deal with the explosive nationalist discourse. Previously multi-national empires had failed to manage nationalist antagonism for hundreds of years. Poland, like many other Eastern European states with regards to its minorities, was undergoing the dress rehearsal for WWII; skilfully capturing human nature’s nefarious capabilities when nationalism and xenophobia are left to take root and flourish.

by Hannah Phillips

Article published with kind permission of crossingthebaltic.com

Close

Close