From a Rollin’ Stone to Moving Mountains or the Process of Democratic Change in Bulgaria

By Slovo, on 15 January 2014

Democracy has solidified into a brittle façade of the actual political system in Bulgaria; the future has become a laughing matter; access to truth is contested and politics has become the dirtiest word of all. Freedom of the press is the second lowest in Eastern Europe according to the 2013 annual report by Reporters Without Borders. The National Assembly is entirely barricaded by a metal wall, while police officers, in their thousands, have spent most of the Christmas holiday guarding the empty building. A few feet down the road, the St. Kliment Ohrdiski University of Sofia remained under occupation for over three months by ‘the Early Rising Students’, who demand their voice and their future back. Daily protests gather in the centre of Sofia and pass through Parliament and the University and block traffic around the evening rush hour.

This is how Bulgarians welcomed the New Year. At midnight on the 31st December in the city square, where thousands of people had gathered to welcome the New Year, the mood was far from festive. Chants of ‘resign’ were outweighing the fireworks as well as the organized concert. This was no time for celebration within a country utterly divided. On 1st January, after more than 200 days of protests, the government approval rate had fallen below 10%, while more than 80% supported the protesters, according to a poll by Alpha Research Agency.

On the eve of 2014, I moved from the square, passed the barricaded Parliament (a barricade that was built a day after the twenty-fourth anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall) and joined the students, who had decided to stay in the occupied lecture hall. If there is a message that I can pass along after spending almost a month in Bulgaria, it is a message of unity. Despite the predictable ripples and difficulties noticeable in the structure of the students and the protest movement, unofficially represented by the Protest Network group, things are changing. From the ground up, reshaping one discourse at a time: rethinking the past, the 1989 revolution, the advent of democracy, the meaning of freedom.

A short retrospect: twenty-four years ago, Bulgaria did not experience that revolutionary change visible in Central Europe. It did not participate in the ground-breaking and seemingly universal process of a ‘rectifying revolution’, of a ‘return to history’, which Jürgen Habermas foresaw in 1990. It was said that countries like Poland and Czechoslovakia revolted against a foreign regime and civilization that hundreds of thousands of people went out in the streets demanding a return to the path of modernity, to progress, to their destiny as part of Europe. It was a process of unfreezing of history, a liberation par excellence.

In Bulgaria, the end of the totalitarian regime resembled a palace coup, in which the old regimes liquidated a highly dysfunctional Soviet-style repressive regime and laid the groundwork for a gradual transition towards a democracy. It laid the groundwork for a very specific kind of façade democracy, where a silent continuity of the past was achieved. Democracy and freedom were granted to the people, who one day were simply told that they had certain new rights and responsibilities. But the meaning of the universal principles of democracy and freedom were significantly altered by the elites in charge of facilitating the transition period.

The biggest and most lasting success of the protest movement, which began as a spontaneous mass public outrage at government unaccountability and corruption, was unearthing exactly how deeply those notions have been altered and who, in fact, is in control of the dominant discourses about the truth regarding the past, present, and the future. It showed how a significant portion of the Bulgarian population, citizens assuming the existence of basic rights and freedoms, have become completely excluded from the political processes and have had their public voice all but silenced. It turned out that their demands for a functioning democracy were not only met by the government but that they were seen as a threat leading to the mobilization of thousands of police officers and the permanent barricading of Parliament. It turned out that Politics was in fact directly dislocated from the people. An effective façade democracy.

Bulgaria, a country known for its troubled path towards democratization, its uneasy energy and geopolitical relationship with Russia, and its highly atomized and isolated society, is changing. On December 26th, in the largest protests of recent months, more than 4000 people gathered in Sofia, from all parts of the world, to join in the struggle for democracy and for a return to Europe. The unofficial organization representing Bulgarians abroad #ДАНСwithmeGlobal co-organized the protest with the Early Rising Students and the Protest Network. It was the first time that a united protest front was solidified and the first time that they all walked, side by side, down the streets of Sofia. And their message is clear: reorienting the country towards democratic consolidation and European integration.

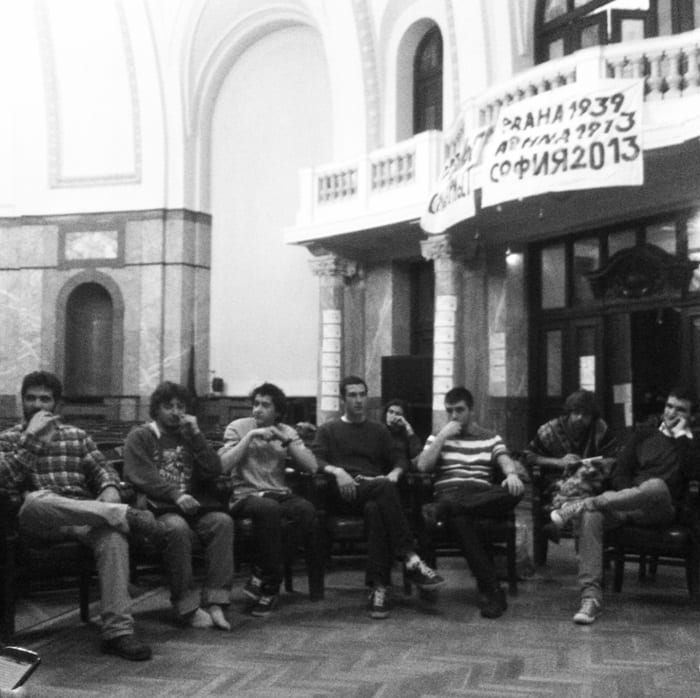

The most vivid symbol of this highly anticipated democratic revival in Bulgaria are the students. They are the ‘children of the transition’, the personification of the political, social, existencial crisis that has marked their nation and their individual biographies. They occupied the University because they saw no options of professional and personal realization in their futures. They refused to remain passive, while an increasingly isolated political elite continued to shape their reality. They wanted to have a say about who they are and who they ought to be.

The students have made one very important step forward – fascilitating public debate. They are organizing round tables, where professors, experts, and politicians will be invited to sit down in the University and discuss the functioning of all the democratic institutions in Bulgaria and how to reorient politics in the right path. It is an important step forward in a highly stifled public sphere, where people often feel their voice, vote, or vision is irrelevant to the actual goings on out there in the State. It is the vital process of (re)consolidating the foundations of a polis. And it is affecting the right of passage to the truth because they represent an increasingly powerful alternative to the official discourse funelled through the mass print and broadcast media in support of those in power.

And those in power represent the highly structured and well financed Bulgarian Socialist Party – the brain-child and beneficiary of the pre-1989 Bulgarian Communist Party. A party infiltrated by ex-Secret Service members with large dossiers, powerful businessmen and politicians; all those who benefited directly both before and after the fall of totalitarianism. The Socialist Party is also the most successful political party and has been in power longer than any other contendor. It has also remained the only party since the very first elections that has avoided dissentigration – until today.

Party members, among which the influenced member of the European Parliament and former Foreign Minister Ivaylo Kalfin, have one by one defected from the party amidst the growing pressure caused on it by the protests. They have joined former President Georgi Parvanov (still a member of the Socialists) in his new political party called the New Bulgarian Revival. This is the first time in recent history that we see a challenge to the left forming in Bulgaria. And it’s big news because, among all else, it is showing a changing political topography.

The protests started off calling for the resignation of the Socialist-led Cabinet amidst emense corruption and unaccountability charges. Over the months and due to continual silence by Prime Minister Plamen Oresharski in connection to those charges, the protests evolved into a powerful discursive alternative regarding both the past and the future – i.e. deconstructing the facades behind the political regime and its geopolitical orientation. Today, the protests have all but fully delegitimized the official discourse presented by the Socialist Party and present a hugely popular alternative about politics, democracy and even the totalitarian past. So successful I might add that it slowly silencing the powerful voice of the Socialist party and all its media backing.

Several weeks ago, broadcast journalists were asking their guests if they were not tired of protesting and the newspapers wrote of the ‘death of the protests’; today those questions seem to resonate of a very different world. Today, the narrative is about when the government will resign – in February or May, when the election for EU representatives will be held. It is a process that emulates the events of 1997, when once again the Socialist Party succumbed to mass outrage at hyperinflation and Bulgarians elected a government set on promoting economic reform and European integration. This time, because the protests have been solidifying for seven months, extending their network, polishing their message, this time change is looking for permanency: a permanent discontinuity of the past – of both its elites, structures and discourses – a vital step forward in the decentered, gradual and positive move towards post-communism (as a way of life) and democracy.

By Nikolay Nikolov

Close

Close