Anti-government demonstrations in Bulgaria, revolution in Ukraine and now the uprising in Bosnia – Nikolay Nikolov looks at the common trends across the Eastern European unrest and examines the critical juncture of these facade democracies.

Some time ago now (1991), Samuel Huntington published The Third Wave: Democratization in the Late Twentieth Century. The idea is that democracy spreads around the world from its core countries in Europe and the US, where developed over a long period of time, eventually extending to the peripheries, which experienced quick transitions from various forms of non-democratic regimes to ranging paths of democratization. Post-communist countries were the third-wave final push with their unseen before dual transitions to a market economy and initiation of democratic processes. The Arab Spring and the easing of the Myanmar dictatorship tickled some to consider the rise of a potential Fourth Wave.

But back in 2002, Michael McFaul sealed the term ‘Fourth Wave’ in a World Politics journal article called ‘The Fourth Wave of Democracy and Dictatorship’. And dictatorship. This is really important. In fact, scholars of democratization like Larry Diamond, Guillermo O’Donnell, Ivan Krastev, Andreas Schedler, to name but a few, have been arguing for a very long time that to speak of waves, of linear progress to democracy and consolidation is empirically and theoretically false. What we see in Eastern Europe, for example, are façade democracy, suspended political authority, lack of civic engagement, media manipulation, questionable (post)Cold-War geopolitical relations – in a word – hybrid regimes, to use Diamond’s term.

Bulgaria, Ukraine, and now Bosnia and Kosovo. A clear path from peaceful protests to chaos and bloodshed. In Europe. Twenty-four (or so) years after the end of the various forms of totalitarianism.

At certain moments, all these nations showed signs of ending their democratic standstill. In Bulgaria, it was the ‘region’s most hailed’ reform period from 1997-2001; in Ukraine, it was the Colored Revolution; for Kosovo and Bosnia – the situation is more complex. But one thing is for certain now, according to Anne Applebaum, the ‘colored revolution’ model is dead: i.e. “the belief that peaceful demonstrators, aided by a bit of Western media training, will eventually rise up and nonviolently overthrow the corrupt oligarchies that have run most of the post-Soviet orbit since 1991.”

The sense of shock and disbelief at what happened in Kiev over the past months has spread to Bosnia and Kosovo last week.

Government Building ablaze in Tuzla

Bosnia is ablaze since Tuesday, when violence erupted in the northern town of Tuzla, a former industrial town, after 10,000 workers were laid off. Their factory was privatized – its investors sold its assets and declared bankruptcy. This, as it seems, was the final straw to an arrogant oligarchic model visible in many post-communist countries. Since then, the protests have spread to more than 20 cities and at least 300 people have been injured. Yesterday, when the municipality building was set on fire, police-officers in Tuzla took their helmets off and joined the protests claiming they “could not hurt the kids”.

Today is a day of clearing the rubble. But it seems that a breaking point has been reached as the monument of the burnt architecture of all that which resembles the ‘corrupt and unaccountable State’ remains.

Photo: Lyla Bernstein

“We haven’t seen violent scenes like this since the war in the 1990s,” says Srecko Latal, an analyst at the Social Overview Service, for the New York Times. Why now? Why not 6 months ago; why not one year ago? These are question that were directed at the protests in Bulgaria, which reached their largest numbers in the summer. Clearly, the situation is so dire that either nothing or anything could trigger public outrage. In Bulgaria, it was the atrocious appointment of corruption-linked and manipulative- mass-media owner Delyan Peevski, that really did it. It seems that in Bosnia – it is the factory closure in Tuzla that has done it.

Over the past years, the country has suffered one crisis after another – political instability have reduced its chances of joining the EU, ethnic divisions are crippling the functioning of democratic institutions, economic hardship has been sustained by a powerful (un)official oligarchic model. Around 30% are unemployed. Many do not have the time or the energy to sustain a peaceful protest and endure a slow, cultural progres towards a functioning democracy and economy.

Of course violence cannot be the answer. It’s destructive. But desperation clearly takes precedence over dialogue in this case. As one student from Tuzla, Lyla Bernstein, told me today: violence is not the answer but ”just the product of collected rage” gathered over the past twenty years. It’s simple – for the people protesting, the assumption of patience is nonexistent. And it is understandable. There is a level of tolerance that is, as has been shown over and over again in the 20th century, very flexible and malleable among human beings. But it has its limits. And within the Balkan countries this year, the sense of tolerance has been exhausted by the outright public arrogance of the Untouchables – call them mafia men, ex-communist, business elites. It makes no difference. Their capacity to flaunt their economic dominance is one thing, but their increasing ability to enforce their political and legal immunity is apparently too much. It has been, for a long time, a fact that democracy is very dysfunctional. People know that and that has been reflected in enduring low-confidence in the public institutions and voting-rates. Bulgaria is the perfect example. But you can look to Bosnia or Albania as well: all countries where the discourse of corruption and ‘the mafia’ has become ubiquitous.

In Kosovo, it was another matter that reached the breaking point of this sense of tolerance. In Pristina, students occupied the University seven days ago. They have been protesting for weeks after reports showed the Head of the University, among other scholars, to have published articles in fake online journals looking for academic credentials. The Parliament subsequently failed to pass a vote on forcing the resignation of the Head of the University. Clashes became violent on Friday as students threw stones and splashed paint on police-officers in Pristina.

In line with Bosnia, Kosovo is hard-hit with soaring unemployment rates (around 40%) and is often reminded that it is one of the poorest countries in Europe since gaining independence six years ago.

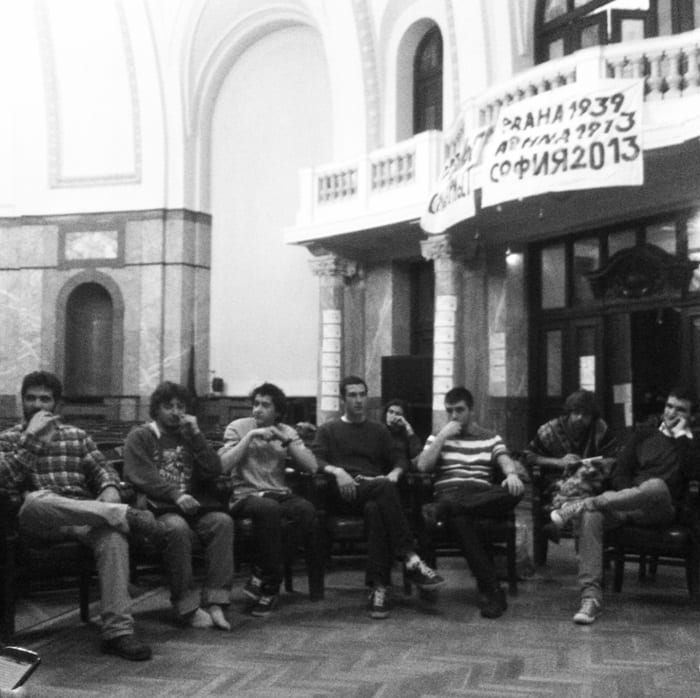

And like in Bulgaria, where the ‘Early Rising’ students occupied the Sofia University (twice) in the past 3 months, the message is the same: ‘Enough. Enough with the circus that the government can claim legitimacy, that the judiciary system is free and fair; this cannot continue any longer.‘

Unlike Ukraine, a country divided into pro-European western Ukraine, and Russia-dominated eastern Ukraine, where #Euromaidan was a direct reaction to steps taken to further isolate the nations from the EU and where the fight is, literally, one of life and death, with clear sides and clear visions of the future, Bosnia and Kosovo and the current signs of violence are a case in point of something else. They have no normative ideal, like the EU for the protesters in Ukraine, which can be emulated; no vision for the future that looks hopeful. The transition period is widely regarded as a fiction only benefiting ‘the few’; and by extension democracy does not literally mean democracy, as it is construed as a mechanism for personal gain and independence.

In Ukraine, the fight is over destroying the foreign influence of a political system; getting rid of the post-totalitarian continuation of the old totalitarian practices.

In the Balkan nations, the fight is about changing the system from the inside. But how can that be done when the people who attempt to do it are marginalized, excluded, silenced, and finally, met with force. In Bulgaria, the biggest weapon against those wanting to rip of the façade of the pseudo-democracy, those who are forcing reform, is the manipulation of the media and the alteration of the truth. Truth is not objective and access is limited. I can see something similar present in Bosnia as the media today are suffocating the public discourse with reports of ‘drug-abuse’, ‘looting’, ‘theft of important archives’, ‘vandalism’.

Bulgaria is in the EU and change is slowly happening, mostly from above with increasingly pressure by the President and, more importantly, by the European institutions. The seven-months long daily protest movement has not as yet managed to force the government’s resignation but has been firstly ignored, then excluded, then ridiculed, and all through-out lied about in the media. Logically, the numbers since the summer have fallen and there is a growing sense of helplessness. But the protesting citizens are not alone; like the protesting citizens in Ukraine are not alone. That does not amount to much, as can be clearly seen today, but it is something that is not present, it seems, in either Bosnia or Kosovo. There, the feeling of desperation at the state of their societies and the feeling of being isolated and alone, is clearly overwhelming. It has lead to a violent escalation. It has brought the international community’s attention back to them. How successful it will be in forcing change is a difficult question, but there has to be a start somewhere. Progress has a point of initiation and that point usually comes with civic (re)engagement.

One thing is clear – democracy does not flow linearly forward. In fact, in many ways it has been altered by the given post-totalitarian regimes, in order to continue the practices of repression from the past. Under the loose notion of democracy, different elites seem able to continue to dominate – either economically, and/or politically, and/or culturally; the one thing they all do is perpetuate the existential crisis caused by the emptiness of the individual transition periods. From Ukraine to the Balkans, the last twenty-four years (give or take) have been an almost uninterrupted period of preaching that yellow is green. “Here, now you have a democracy;” you are free now!” is the visible stream, while the underwater current has been one of underwriting each and every single democratic institution, atomizing individuals through economic hardships and bad politics, and reducing freedom to pseudo-political independence.

So what is a potential step-forward? Realizing just how deep this underwater current runs in the given society; understanding just how much of a façade there is, how much of a hybrid regime one is facing, and after that really getting back to the basics of democracy, literally: ‘rule (kratos) of the people (dēmos).’ One such initiative that is gaining ground in Bulgaria is an initiative boycotting buying goods from the corporate ‘corner-shop’ Lafka, which is co-owned by Head of the National Security Agency to be Delyan Peevski. Another is the student occupation, which gained incredible public support (almost 80%) after its initiation last year. This seems to be working in Pristina as well but we should wait and see how that develops over the coming weeks.

When the government is unaccountable, when there is an oligarchic economic model, when the media are not independent, when you are a poor European nation, the only way to overcome the incredibly diverse forces of post-totalitarian repression is to actively, collectively, and in a decentralized manner, negate, oppose, ridicule the status quo. Alternative paths to reform need to be tried out and peaceful resolution, obviously, requires precedence. A counter-discourse against the alteration of truth in the public domain must pursue – Facebook seems to be a successful tool for that, for now. That has already happened in Bulgaria and Ukraine. The next step is national engagement – we can see that currently happening in Bosnia. Eventually, the forces will become too strong. The biggest obstacle of isolation from the political process and the reduction of democracy to pseudo-elections can be overcome. One thing that is certain is that when change is forced through, it will not presuppose progress immediately. It will, however, level the playing field, initiate a process of political healing and jumpstart the institutionalization of democracy. One step at a time.

By Nikolay Nikolov

For more from Nikolay visit http://banitza.net/

Close

Close