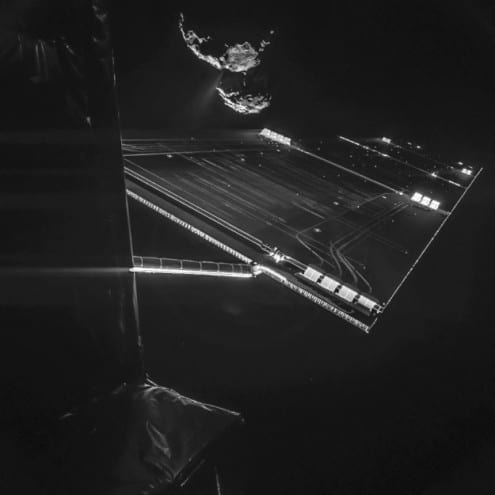

Comet C-G, seen by Rosetta’s NAVCAM on 6 November 2014. Philae’s landing site is towards the top of the image. Credit: ESA/Rosetta/NAVCAM – CC BY-SA IGO 3.0

After a decade of travelling around the Solar System, the Rosetta probe is now at its destination: Comet 67-P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko (or Comet C-G to its friends).

The Rosetta mission is made up of two parts which have spent the last decade bolted together: the orbiter, and the lander, known as Philae.

Just after 9am GMT on Wednesday, Philae will separate from the mother ship and begin its descent to the comet’s surface. Around seven hours later, if all goes well, it will touch down on C-G’s rough surface.

This will be the first ever landing on a comet.

The gravitational force between two objects is directly proportional to their masses and the distance between them. Philae, at around 100kg, weighs much the same as a (large) human being, but the comet has a tiny fraction of the Earth’s mass. The pull between them is therefore minuscule – of the order of the gravitational force experienced by an object weighing just one gram on Earth.

Even though Philae will only be approaching Comet C-G at walking pace, the low gravity means it will need to attach itself to the surface with a harpoon to avoid bouncing back into space.

Because of this, the manoeuvre has been compared to a ‘docking’ rather than a ‘landing’.

UCL’s Prof Andrew Coates is a member of the Rosetta Plasma Consortium, which will be monitoring the plasma environment of the comet during Philae’s descent and landing. (He was also closely involved with the design and construction of Rosetta’s scientific payload.) He will be at mission control in Darmstadt on Wednesday as the lander begins its descent.

“The Rosetta orbiter and lander provide unique perspectives on how comets interact with the solar wind and on charged dust from the surface. The historic landing attempt will be a huge opportunity for coordinated observations,” says Prof Coates.

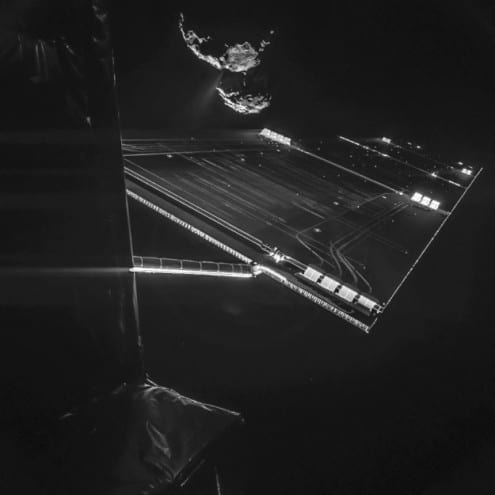

Comet seen over Rosetta’s solar array, 14 October 2014, when the comet was around 16km away. Credit: ESA/Rosetta/Philae/CIVA (All rights reserved)

Links

High resolution images

Close

Close

Apollo 11, which touched down in the Sea of Tranquility on 20 July 1969 was the first manned landing on the Moon. But prior to the human spaceflight project, NASA explored the Moon with robotic probes. One key element of this endeavour was the Lunar Orbiter programme, which included five spacecraft that mapped almost the entire lunar surface in 1966 and 1967. This was in part in order to identify landing sites for Apollo, but the missions also had broader scientific goals.

Apollo 11, which touched down in the Sea of Tranquility on 20 July 1969 was the first manned landing on the Moon. But prior to the human spaceflight project, NASA explored the Moon with robotic probes. One key element of this endeavour was the Lunar Orbiter programme, which included five spacecraft that mapped almost the entire lunar surface in 1966 and 1967. This was in part in order to identify landing sites for Apollo, but the missions also had broader scientific goals.