After two years of repairs and upgrades, the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) is back in operation – and UCL scientists are at the heart of the action. Engineers at CERN confirmed today that the beams of protons that circle in the 27km tunnel near Geneva are stable, and scientific data is once again being collected.

The ATLAS experiment is made of concentric rings of detectors (the particle beam passes through the centre), as seen here during shutdown in 2008. Credit: CERN/Claudia Marcelloni De Oliveria (CERN licence)

UCL scientists have been closely involved in the design, construction and operation of ATLAS, one of the giant detectors that track the high-energy particle collisions in the LHC, so this is an important milestone for the university’s High Energy Physics group.

Until now, the LHC has not been operating at full power. The faults that led to its shutdown shortly after it was inaugurated in 2008 meant that it could only be used to accelerate particles to around half the energy it was designed for.

* * *

Einstein’s equation E=mc2 states that energy and matter are interchangeable.

Atom bombs, famously, create vast amounts of energy by destroying small amounts of matter.

Particle accelerators like the LHC do the opposite, pumping vast amounts of energy into tiny particles, making them move at close to the speed of light. When they collide together, some of that energy is converted into extra matter, in the form of new particles flung out from the site of the collision. The greater that energy, the heavier the particles that can be generated.

Physicists describe the world around us using the ‘standard model’ of particle physics, a set of a handful of particles which can explain the properties and makeup of all the matter and energy we see around us.

The last of those particles to be detected in the lab was the Higgs boson, discovered at CERN in 2012 shortly before the upgrade began.

This doesn’t mean there is nothing left to discover, though. Scientists, including CERN’s director, have begun speaking of a tantalising ‘new physics’ – whole new uncharted areas of science that are currently totally unknown, but which might be explored with higher-energy collisions and heavier particles generated.

One of these areas could be a solution to the riddle of dark matter.

Dark matter can be detected by astronomers (as seen in this Hubble image of a galaxy cluster), but it has not been spotted on Earth, and is known to not be made out of any of the particles in the standard model. Credit: NASA/ESA (CC-BY)

Dark matter has been detected in distant galaxies, thanks to its gravitational effects, but astronomers have determined that it cannot be made of any of the particles described in the standard model.

ATLAS, the building-sized instrument that UCL participates in, played a key role in the Higgs boson discovery, and will play a starring role in the future work of the LHC, and could help explain how dark matter relates to the standard model of particle physics.

* * *

The LHC consists of two 27km-long pipes that use powerful magnets to accelerate beams of protons in opposite directions.

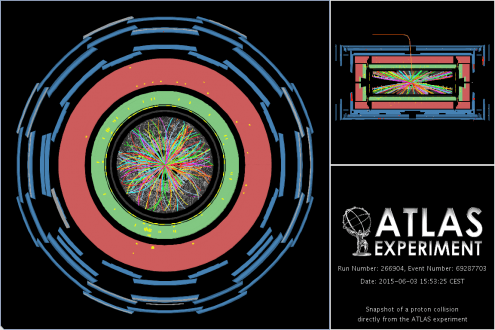

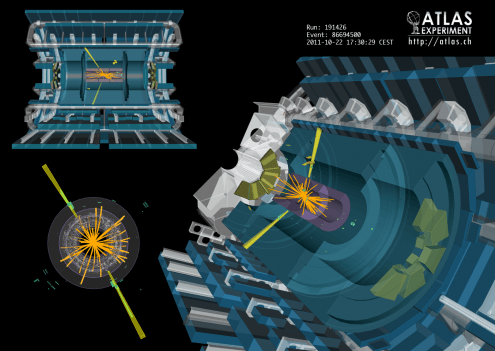

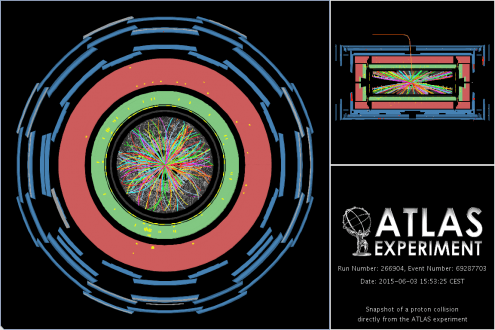

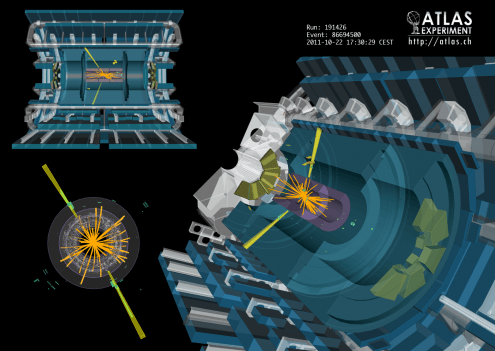

Inside ATLAS, the two beams are brought together on a collision course. The beams are not continuous: the protons come in pulses (“bunches”) about 10cm long and the width of a human hair, each containing around a hundred billion particles. When these bunches cross each other, protons collide and new particles cascade out through the concentric rings of detectors that make up the ATLAS experiment.

One of the detections made by ATLAS today. This picture is a cross-section of the instrument, with each concentric ring detecting particles’ location or energy, and the particles’ tracks (shown as multi-coloured curved lines) inferred from this data. Credit: CERN (CC BY SA)

Scientists can then trace the path that the particles took – and determine their energy, mass and electrical charges. And from those, they can infer the process that take places in each proton-proton collision.

During the two-year LHC shutdown, the ATLAS scientists also made several improvements to their detector, most notably with the installation of an extra ring of detectors close to the beam pipe, making it more precise than ever before, and part of the team’s work now that the LHC is running again is to ensure that this is all properly calibrated and working as expected.

When it runs at full capacity, ATLAS detects 40 million particle collisions every second, far more than could ever be studied.

Part of the challenge is to discard the unimportant data so that scientists can focus on what’s important. One of the major contributions UCL scientists have made to ATLAS is to the design and operation of the hardware and software algorithms used to discard trivial events in real time and select only the interesting ones – reducing 40 million collisions per second down to a far more manageable 1,000 that are recorded offline.

Another challenge is the simple matter of timing and synchronisation.

With millions of events per second, and everything moving at close to the speed of light, untangling the data from different collisions is challenging. ATLAS is still detecting particles ejected by one collision while another is already taking place.

Particles from multiple events cascade through the detectors at one time, and synchronising them is not straightforward. Credit: CERN (CC-BY-SA)

UCL scientists played key roles in developing the electronics that ensure that the data is accurately recorded and readouts from the different components of ATLAS are all kept properly synchronised.

* * *

So what’s next for the LHC?

It’s very hard to say – and that’s what is so exciting about particle physics today.

The standard model is complete. There could be a radical departure, revealing areas of physics never explained before.

Equally, there might just be further confirmation of the dramatic discoveries of the past few decades, giving more precision and certainty to the standard model.

In either case, there is now a chance to explore physics without the constraint of theoretical preconceptions – an unusual and liberating place for a physicist to be.

With thanks to Prof Nikos Konstantinidis for help with this article

Close

Close